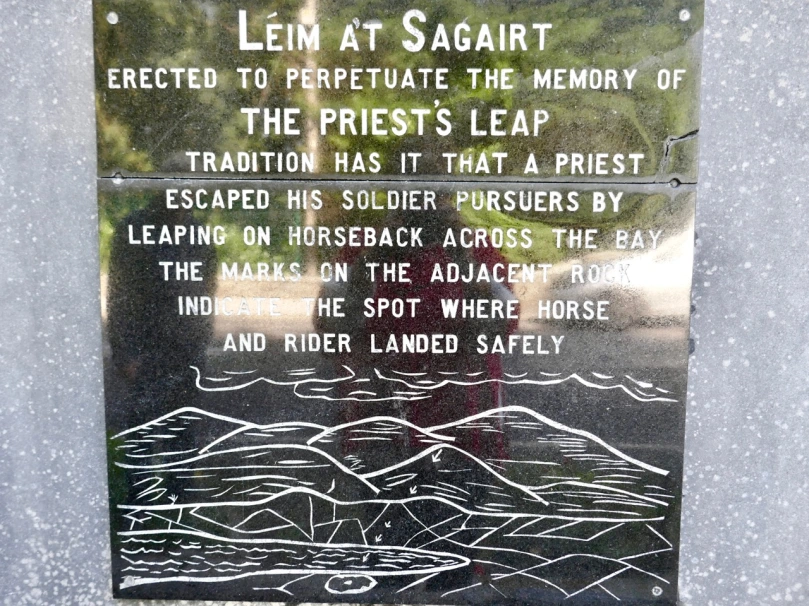

Bullaun Stones abound in Ireland. They are usually found nowadays at sites with ecclesiastical connections, as in the example above at Maulinward, an ancient West Cork burial ground. This association does not reduce or affect their traditional uses – according to folk convention – to cure or to curse. The Irish word Bullán means ‘bowl’ – a water container. At pilgrimage sites, such as St Gobnait‘s, Ballyvourney (below), the bullaun stones often hold quartz fragments or smooth, rounded pebbles – perhaps incised with a cross – which are turned around each time a pattern or procession is completed.

The Maulinward example on the header picture shows how the tradition of making offerings at some of these locations continues to this day. At other sites, such as the one below, the hollowed-out stone filled with rainwater takes on the properties of a holy well, and is visited for cures or simply good fortune.

This example, outside the door of the church at Cill Lachtáin, Co Cork seems to have been mounted to perform as a holy water stoup: the plaque reads ” . . . This blessed font of Cill Lachtáin was standing in Cloch Aidhneach from 600AD to 1600AD . . . “ Others resemble fonts and are similarly associated with places of worship. Look at this striking stone from Timoleague Friary, whose purpose – according to tradition – is clearly stated:

In the sixth century, the Council of Tours ordered its ministers ” . . . to expel from the Church all those whom they may see performing before certain stones things which have no relation with the ceremonies of the Church . . . ” Such an order doesn’t seem to have prevented folk customs of curing continuing into the twenty-first century.

The ongoing use of bullauns as fonts, stoops or holy wells does not explain their original purpose (which is probably pre-Christian: here’s an interesting conjectural world view of the phemomenon), and it’s quite likely that we will never fathom for sure what they were for. The example above, at Kilmalkedar, Co Kerry is as enigmatic as they will get, with its multiple ‘basins’ carved into a large earth-fast boulder isolated in the middle of a field, although not far from a remarkably complex ecclesiastical site. But the one I find the most fascinating can be found along the Priest’s Leap road, a mere few steps away from our own home in West Cork . . .

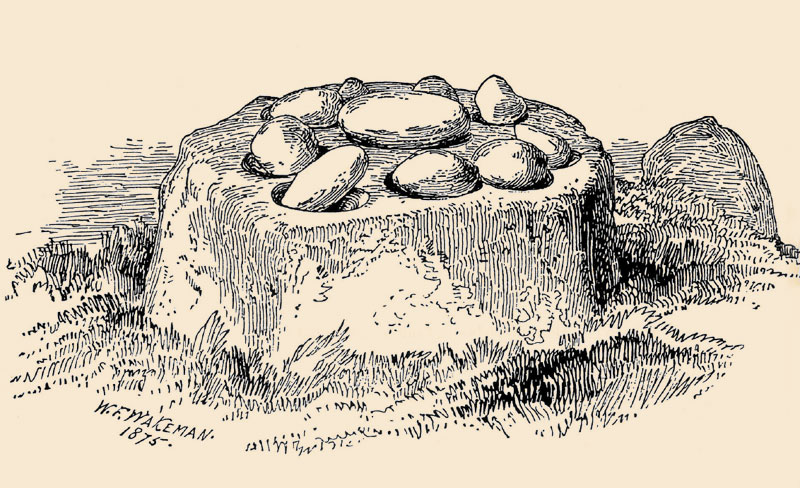

This rock outcrop – known locally as The Rolls of Butter – is large (I’m there to give it scale!) with seven scooped-out bullaun like basins and a somewhat phallic central upright stone. The basins each contain a large, smoothed pebble. Some folk traditions in Ireland identify such pebbles as ‘cursing stones’: “. . . if you wanted to put a curse on someone, you turned the stones anti-clockwise in the morning . . . ” However, the curse had to be ‘just’ otherwise it came back to curse you in the evening! The illustration below – of ‘cursing stones’ at Killinagh, Co Cavan was made by antiquarian W F Wakeman in 1875. He also noted the similar local folk traditions of these examples.

Many bullaun stones or stone groups around Ireland have been included in the National Monuments records, and number in the hundreds. Functional, magical, sinister? Who knows . . . Your guess is as good as anyone else’s. But one thing is certain – they are intriguing and mysterious. Keep a look out for them – as we do – in your travels around this land.

Note: this is a re-run of a post I published five years ago – but it’s been augmented, updated and – hopefully – improved!