As a finale to this little series on Ireland’s Electrification Ventures back in the 20th century, I’m taking you on a tour of Ardnacrusha. This generating station – powered entirely by water from the River Shannon – was the largest in the world when it was built by Siemens, between 1925 and 1929. Siemens AG is the foremost industrial manufacturing company in Europe, and its Irish connections began in 1874, when Siemens laid the first direct electrical cable across the Atlantic, linking Ballinskelligs Bay on Ireland’s west coast to North America. The pioneering continued, in 1883, when the company built one of the world’s first electric railways, linking Portrush and Bushmills in Co Antrim. After Ardnacrusha, Siemens became responsible for many of Ireland’s landmark achievements, including the ESB’s first pumped storage power plant at Turlough Hill; the DART rapid transport network; the baggage handling systems for Dublin Airport’s Terminal 2; and – in 2016 – the orders for Galway Wind Park – then the largest in Ireland.

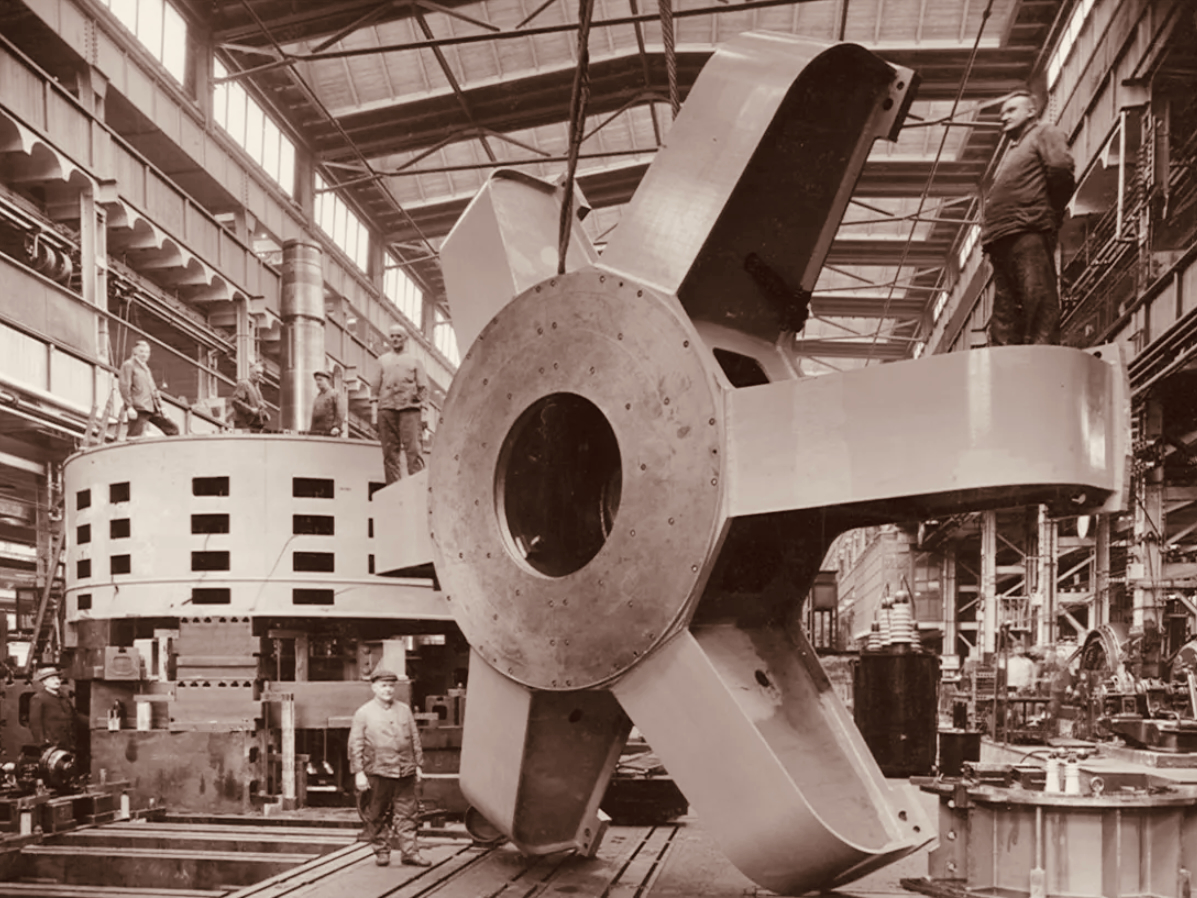

The header pic shows one of the three vertical-shaft Francis turbo-generator units after construction. These were joined by one vertical-shaft Kaplan turbo-generator unit between 1933 and 1934. Above is one of the penstocks which brings the water into the turbine casings.

. . . The construction of the Shannon Scheme was a mammoth undertaking for a country the size of Ireland, especially when the State was barely three years old. The project cost £5.2 million, about 20% of the Government’s revenue budget in 1925 . . .

ESB DOCUMENTS

Visitors to Ardnacrusha in the turbine house on opening day, 22 July 1929 (ESB Archives). Below – a part of one generator awaiting installation (ESB Archives).

We joined a group visiting the generating station in early July. It was a great and satisfying experience! Safety was the top principle, but we got to see all the features of the whole set-up. If you want to go, book in advance – it’s free – and fascinating (if, like me, you are moved by engineering and history).

The pound lock at Ardnacrusha: it provides navigation for boats through the dam. At a drop of 100ft – 30 metres – it’s the deepest lock in the whole of Britain and Ireland. Following is a pic of a traditional British narrow-boat – NB Earnest – traversing the lock (Irish Waterways History).

The main building at Ardnacrusha has a definite sense of ‘Bavarian Character’ to it – probably because of its German roots. I wonder if that’s the reason it escaped being bombed in World War II? Concerns were definitely expressed that this could have happened, and steps were taken to mitigate any possible damage. I was particularly impressed by these one-person air-raid shelters, which have been preserved because of their historical interest:

Here’s the ‘back end’ of the main building block, showing the position of the canal lock but also the new architectural-award winning control room – copper sheet clad – which has taken the place of the original room and desk, which have nevertheless been preserved as a piece of history:

The machine above cleans the weir intake grills leading to the turbines. Everything here has its historical aspects emphasised, where relevant. The wondrous machine above is in full working order to this day, cleaning the intake grids on the weirs coming in from the main dam. A replaced turbine impeller is used as a decorative fountain feature beside the driveway into the station:

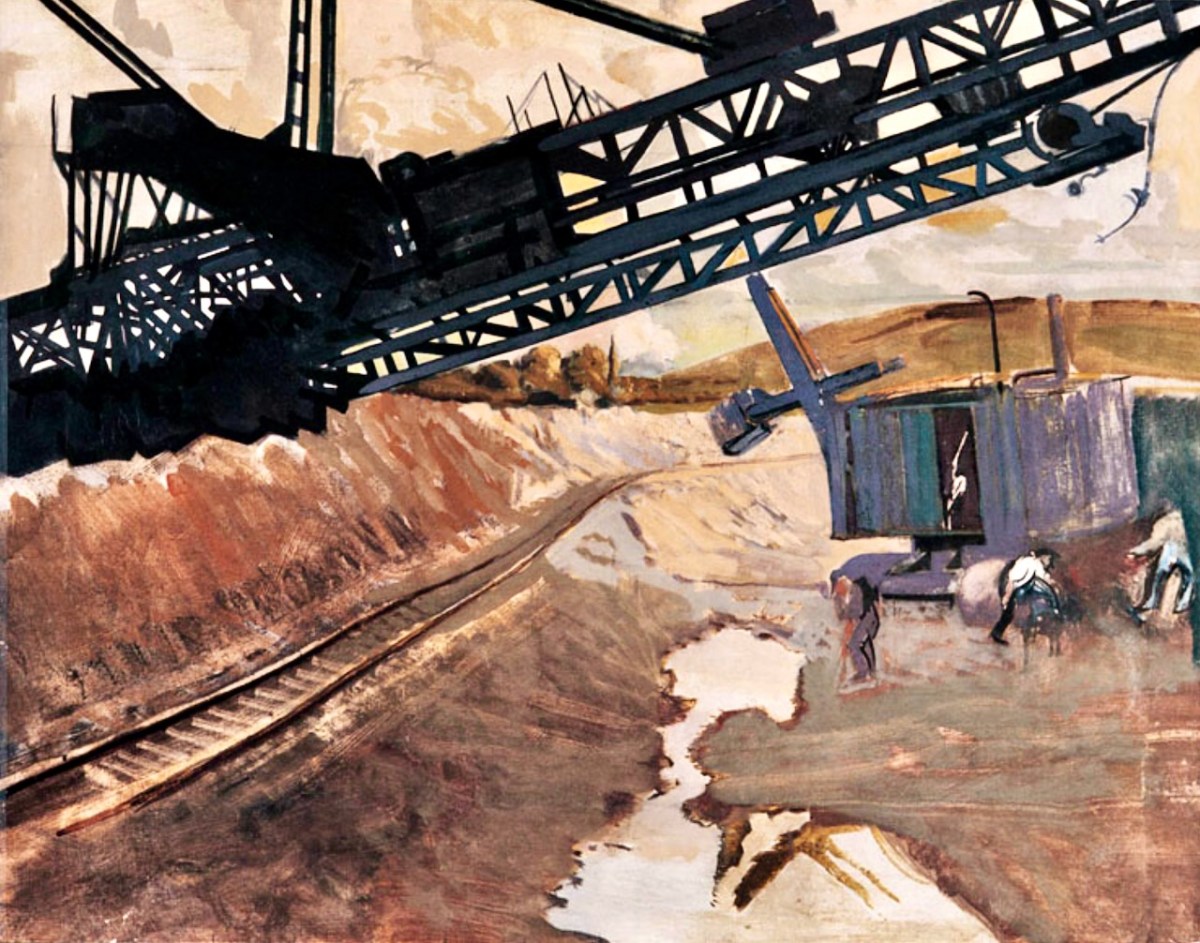

In a previous post, I mentioned that the artist Seán Keating was so impressed by the project that he painted a series of canvases during the construction process. The majority of these originals are now on display in the power station offices – accessible on the tour.

I once again express my thanks to Michael Barry for setting me on this rewarding path. I understand he is giving electrification and Ardnacrusha due mention in his forthcoming book A Nation is Born.

Further information on the Electrification of Ireland can be found in these posts: