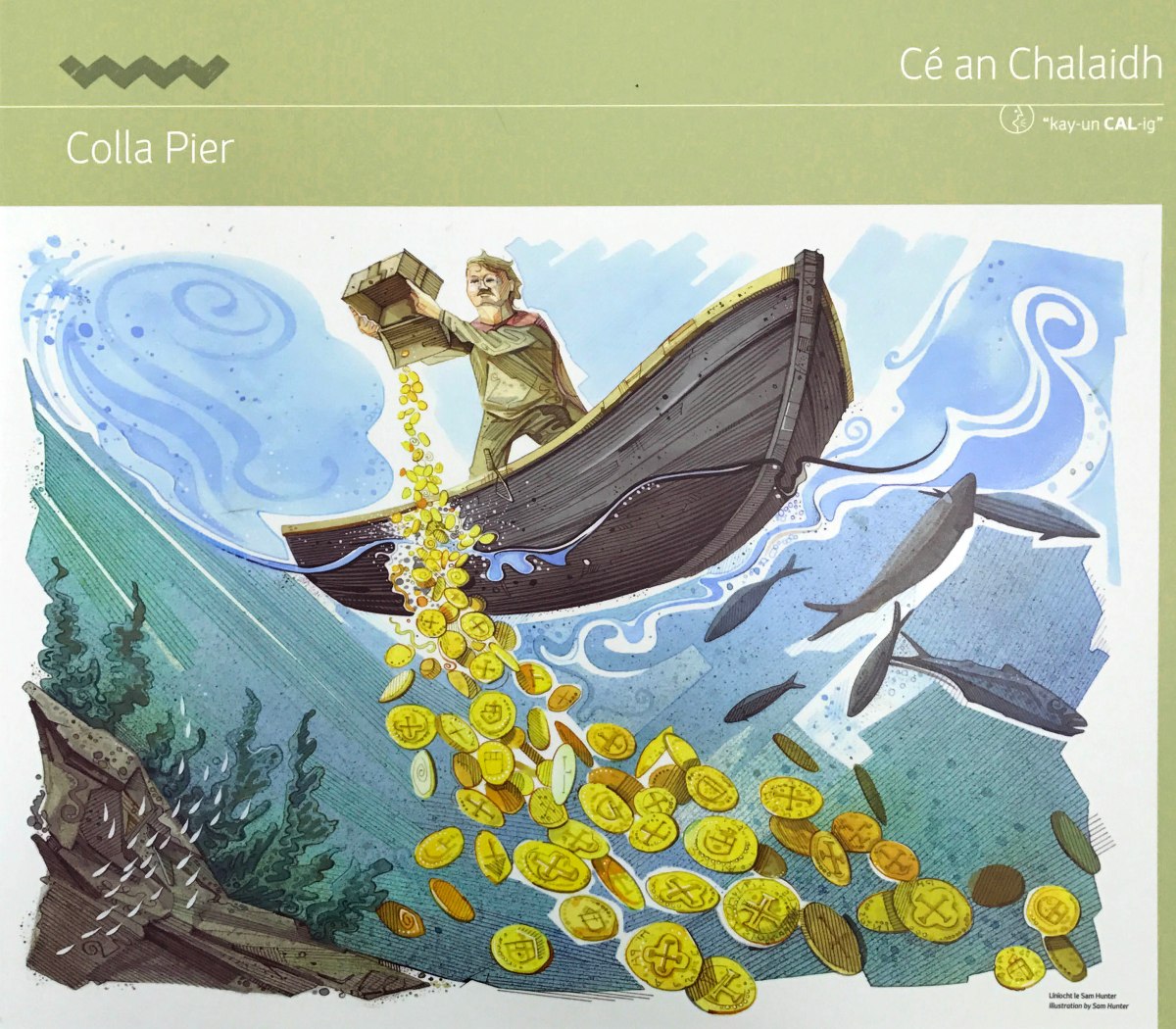

I can give you a little more information about the Goat Islands now, thanks to Jim O’Keefe, the fount of all wisdom in regards to Schull History. First – the name Lough Buidhe (Pronounced Bwee) – I had forgotten that there is significant folklore associated with this area. Jim tells me that it was believed that gold coins were to be seen on the sea bed as a result of a ship wreck on the Barrell Rocks. But there’s another story too, one that is illustrated in the information sign at Colla Pier.

This one features Fineen O’Driscoll, chief of Baltimore and you can read Robert’s account of it in his post A Watery Tale. As backup – here is my photo of Robert taking it all in, in 2017.

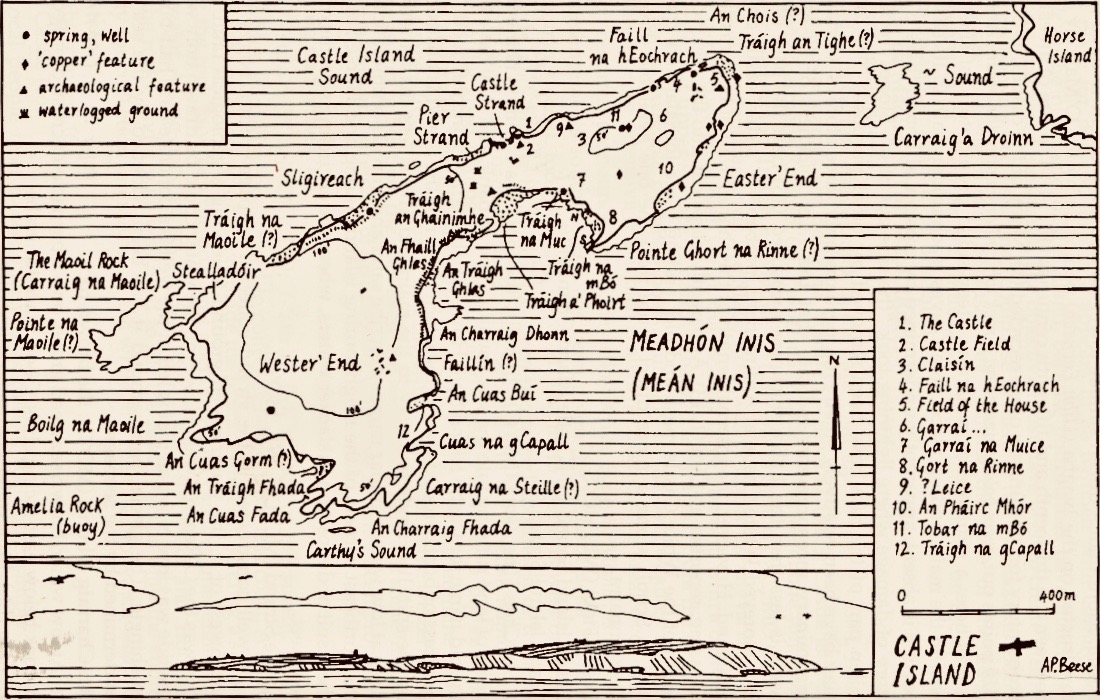

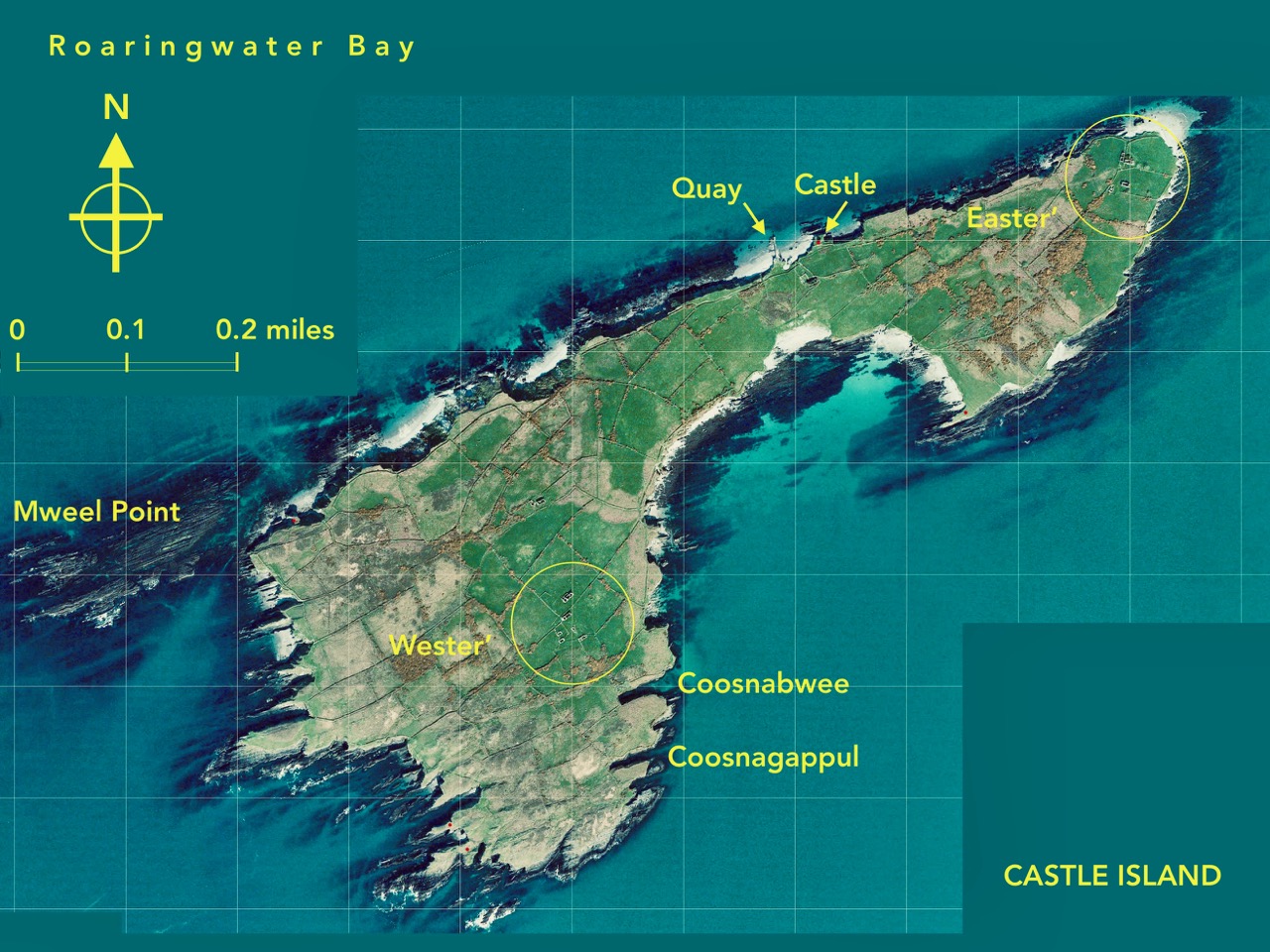

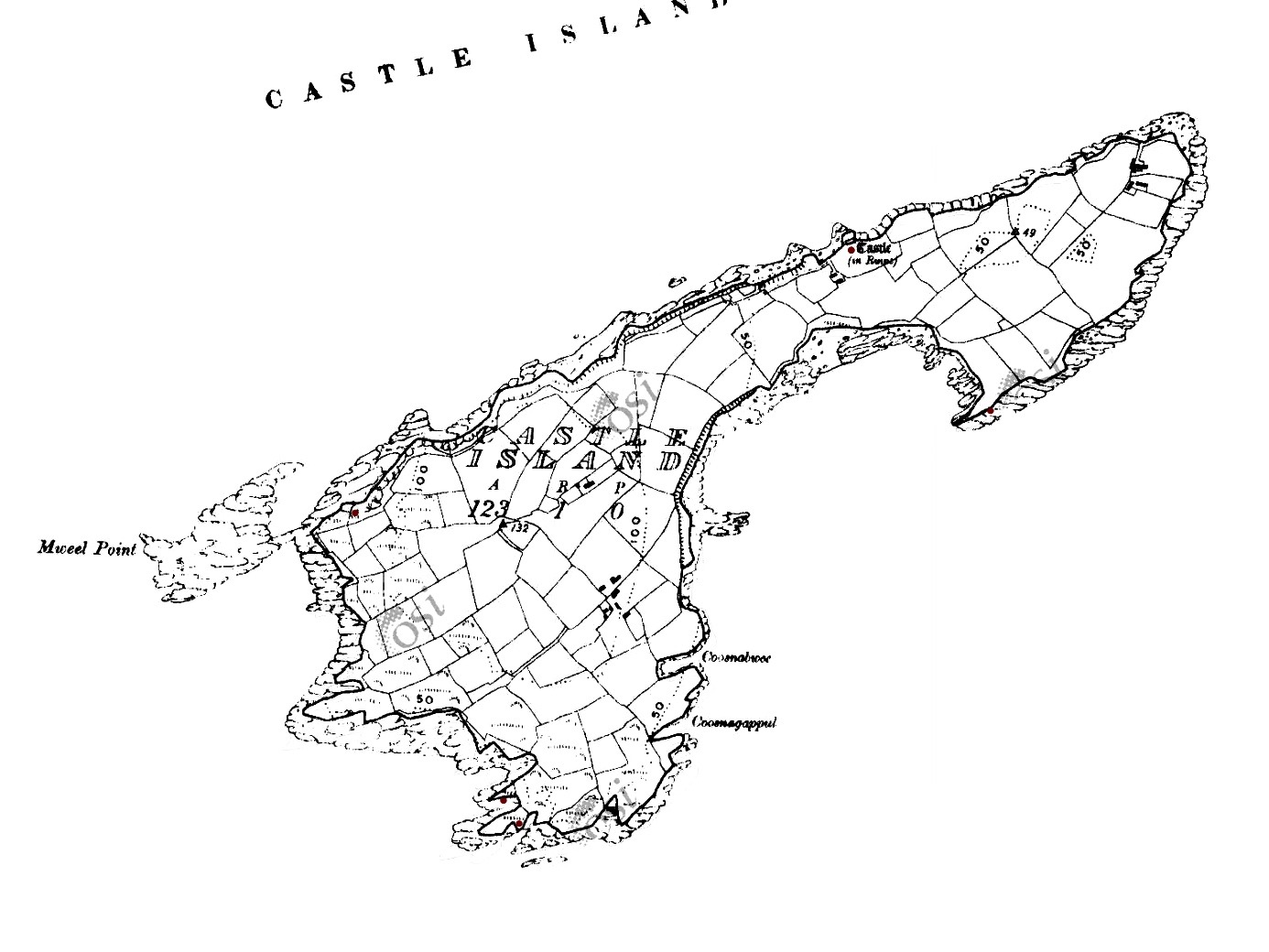

Second, Man of War Sound – Jim tells me this is a mis-translation of ‘Mean Bothar’, main road, or main entrance into Long Island Sound. Here we are in that sound, with Leamcon Castle in view.

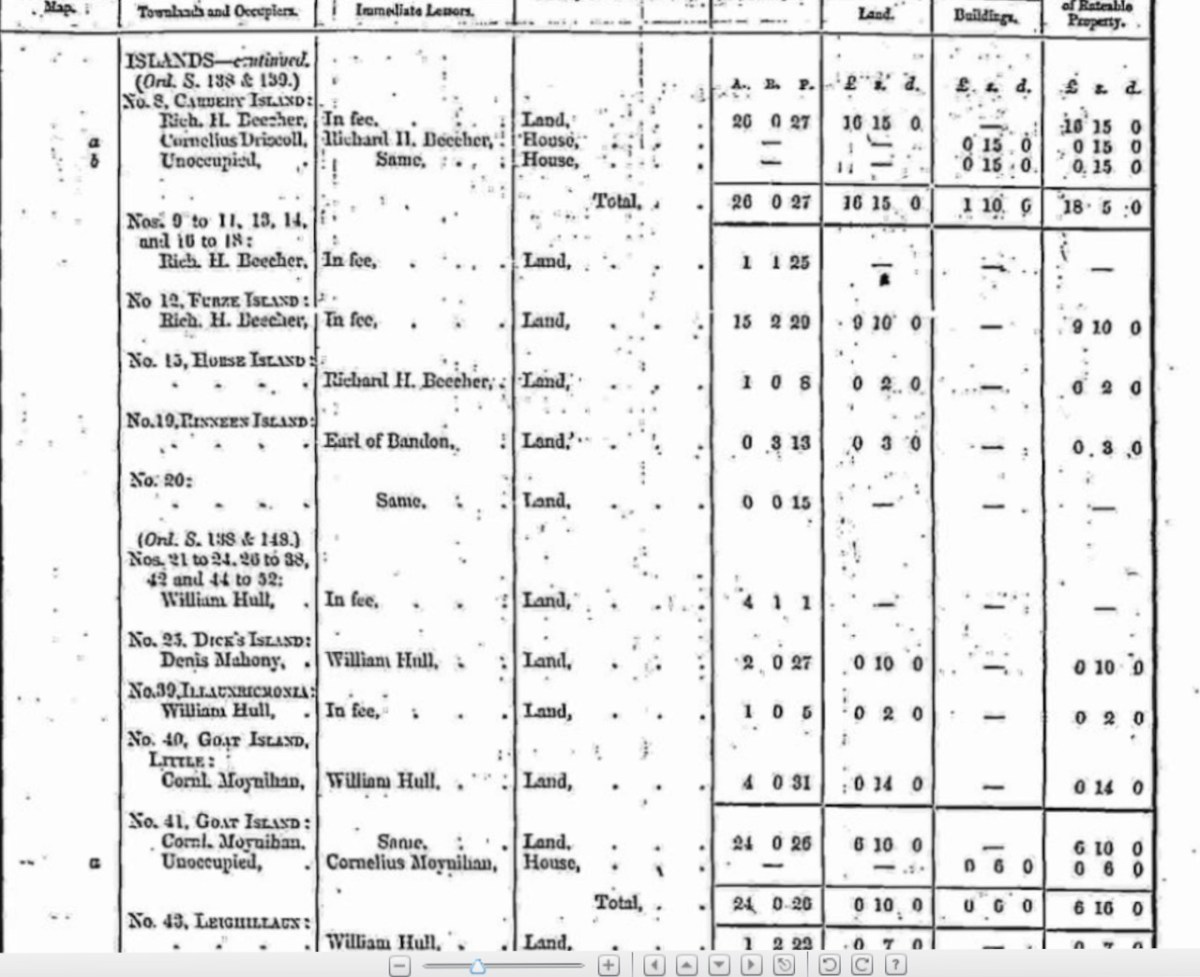

I was wondering who owned the island – Jim told me the owner also owns Coney Island. He bought the Goat Islands thus:

He bought the islands from Nelly Downey; I was the auctioneer acting on Nelly’s behalf. Nelly wanted thirty five thousand for the islands. He thought that too much and offered twenty five thousand. Nelly dismissed us at the door of her cottage with the words: “thanks very much bye”…repeating “it’ll need no salt” …. “good day and good luck.” As we walked away he said to me : what was she saying? I said “It will need no salt” Mike was highly amused and said I must buy it so . We returned to Nelly and sealed the deal .

The owner, with his daughters, did some work on the stone cottage. In the gap in the south side of the main island there is a nice sandy cove and a large flat rock, ideal for sun bathing.

On the eastern end of the main island there is a ‘cuas’ with stone steps cut into the rock, making landing there possible. Apparently a lone man lived on the island at one point. On the Little island there is a rock on the east side with a mooring point on it to facilitate lading there .

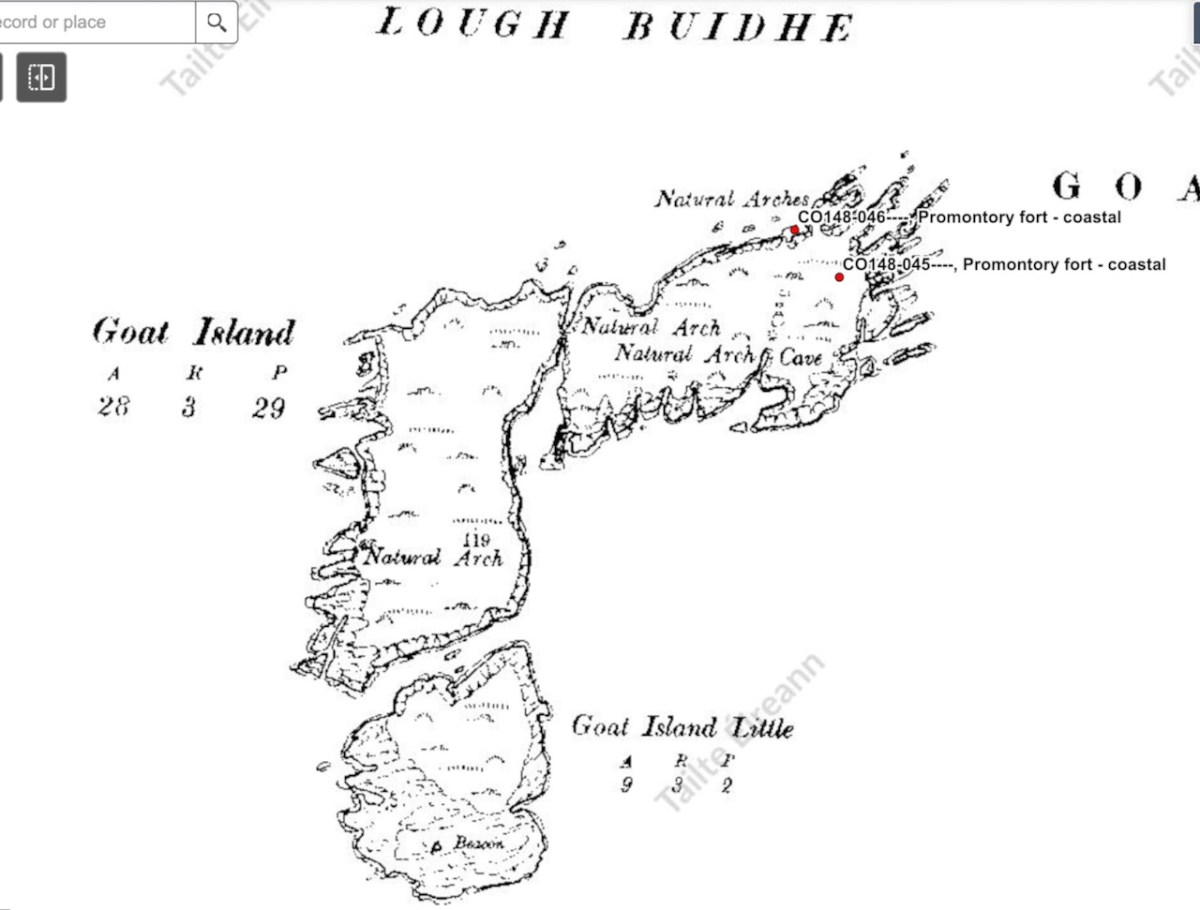

I wonder if the Lone Man was the elusive Cornelius Moynihan? A Cuas is a small cove. Jim also reminded me that Goat Island is also known as Goat Island Great. We didn’t see the Cuas, but did get great views on the sea arches on the north side of Goat Island Great.

In my last post I told you there was more to the story of our morning on the sea. First – we turned around and went back through the Gorge from the other side. This video has a reminder not to take the depth of the water for granted.

Just when I thought Nicky would turn for home – after all, I was now totally satisfied with my marvellous adventure – it became apparent he had other ideas. It was a fine day after all and it would be a sin to waste it, so off we set across Roaringwater Bay in search of dolphins. Nicky explained that Atlantic waters pour into the Bay through Gascanane Sound, between Sherkin and Cape Clear, bringing the fish with the tide, and the dolphins chasing the fish. We did see two dolphins but only a glimpse and they were gone. That’s Cape Clear below – the distant buildings on the headland are the original Fastnet Lighthouse and the Signal Tower.

As we threaded our way back through the Carthys, Nicky had another surprise for me. This is a significant habitat for seals. There are two seal species in the waters around Ireland – Harbour Seals (aka Common Seals) and the larger (and actually more common) Grey Seals. I am, alas, totally ignorant about seals, but I think these were Harbour Seals (corrections welcome). ** Correction received – see Julian’s comment below.

Nicky pointed out that the seals like to keep an eye on whatever gets too close. He pointed out that some scouts has slipped into the water and were now behind us. Another couple were abreast of us, on either side, perhaps making sure we didn’t get too close to the colonies.

As Nicky slowed down a haunting sound came drifting across the waves. It was the seals vocalising. I had never heard this before and was immediately captivated. Wild and resonant, mournful and moving, soul-stirring and plaintive – it was a sound that seemed to reach inside me and conjure up the watery undersea realm of selkies, those mythical half-seal half-human creatures.

And that, in turn, of course, brought to mind Port na bPúcaí (purt na boo key), or Spirit Music. This is how Robert told the story in his post Troll Tuning:

Port na pBúcaí (Music of the Fairies) is a haunted song if ever there was one. It’s said that the islanders were out fishing in their currachs when a storm broke out. It turned into a gale and they feared for their lives as the canvas hulled craft became swamped. Then, the wind suddenly died and they became aware of music playing somewhere around them – an unearthly music. The island fiddler was amongst the crew; when they got safely back to land he found he could remember the tune they had heard. It has passed into the traditional repertoire and has been played ever since.

Púca (pronounced pooka. Plural Púcaí, pronounced pookee), can be translated in a number of ways, but a Púca is generally considered to be a mischievous spirit. And here is Robert’s own rendition of Port na bPúcaí on his concertina.

We were only gone a morning. It felt like an Oisín-like lifetime.