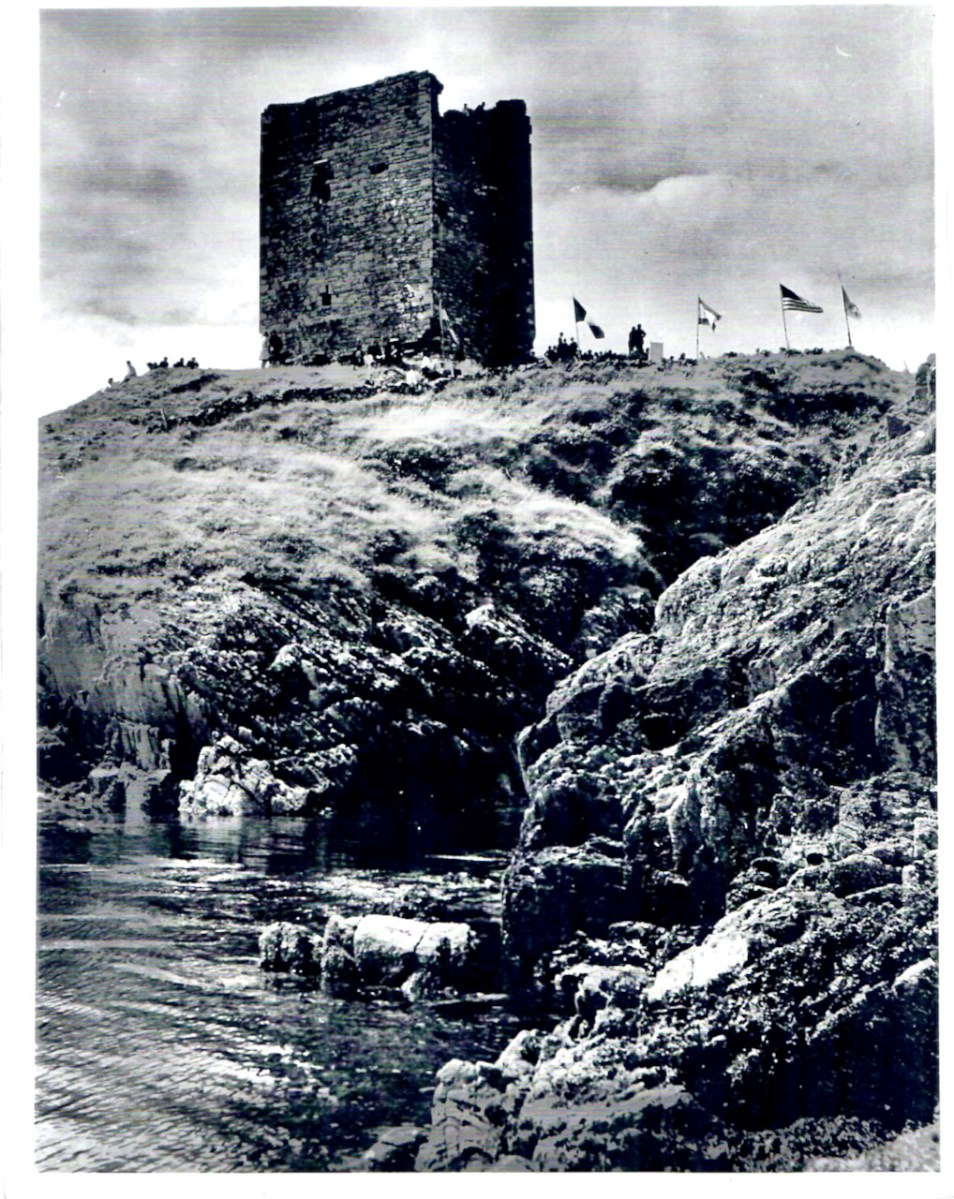

This post will be about the castle itself, as a follow-up to Part 1 about the promontory and historical background. I received some very interesting comments on the name, Dún an Óir, which I interpret as Fort of Gold, and I will write more about that at the end of this post. If you are not familiar with castle architecture, before you start, you might want to browse my castles page and pay attention to how they were built and what the castles of Ivaha generally looked like. Unless otherwise identified, all the photographs in this post were kindly sent to me by Tash, one of our readers. In this one, taken from the sea, the impregnable siting of the castle can be appreciated.

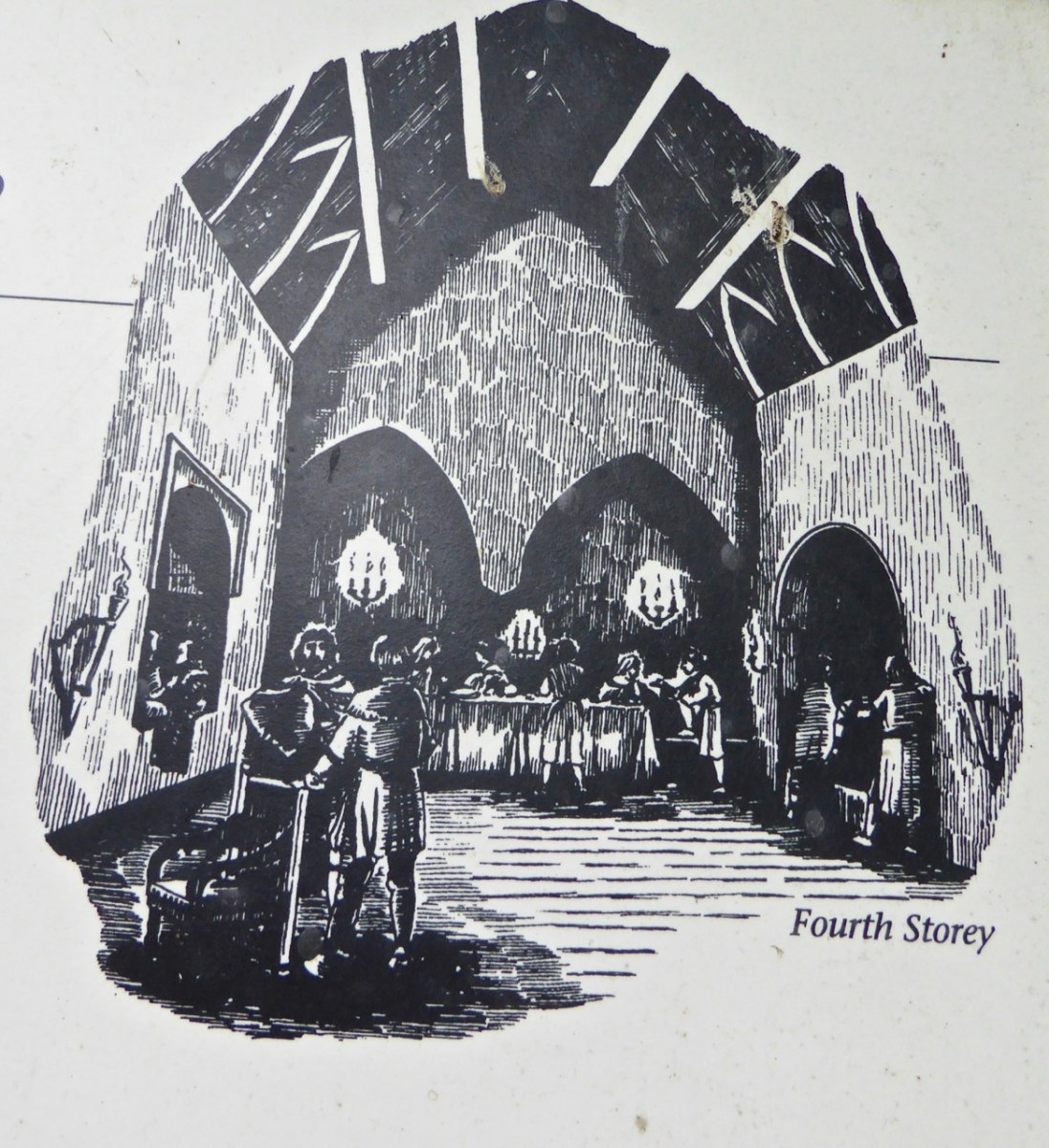

The castle was surrounded by a bawn wall, clearly visible still. Three floors (ground, first and second) were surmounted by a ‘partial vault’, above which was the principle chamber or solar – the private domain of the castle owner and his family but also where visitors were entertained. Above that was a mezzanine floor and above that again was a wall walk, accessed via a spiral staircase from the main chamber.

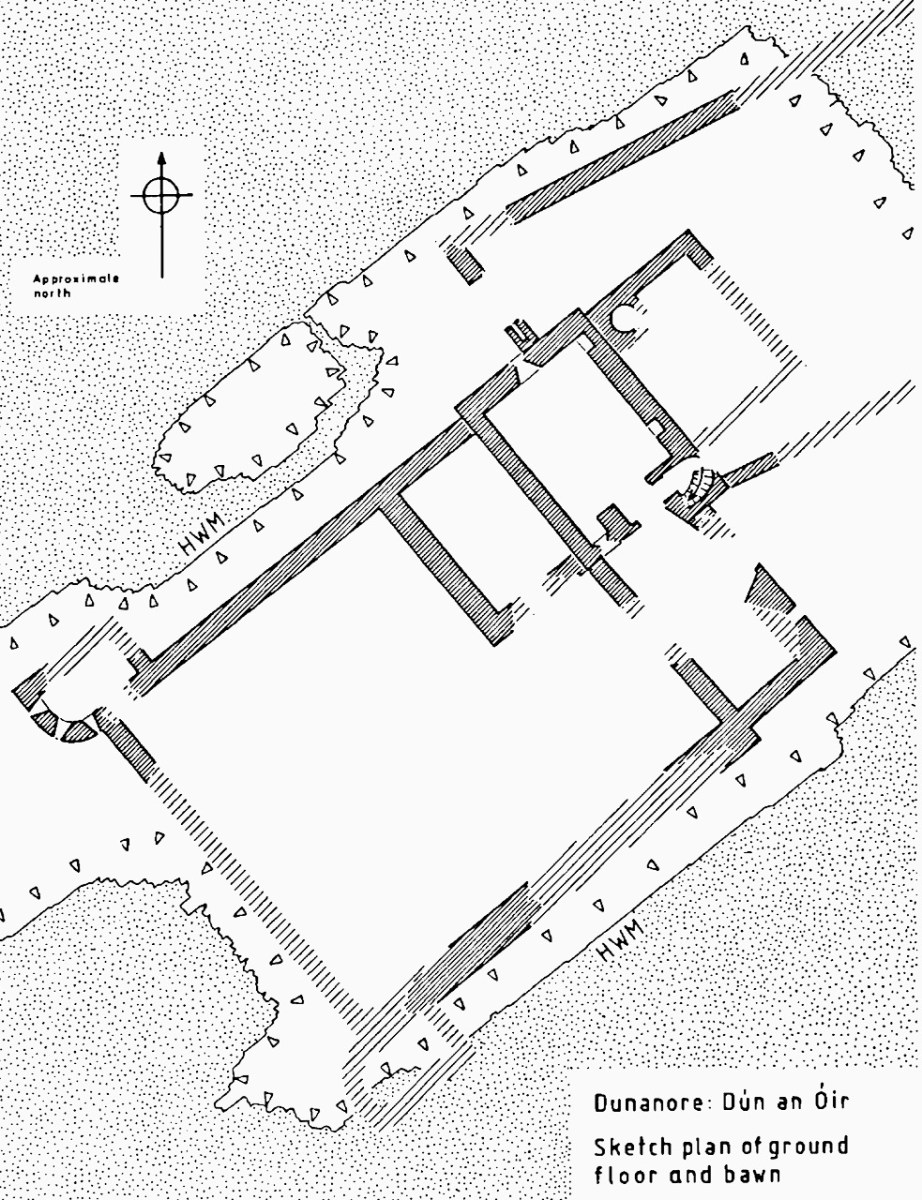

In her paper on this castle*, Sarah Kerr points out that it is, in fact, unlike the other O’Driscoll Castles of Dún na Séad and Dún na Long, and indeed other West Cork Castles, in that it only had one entry, at the ground-floor level. It is possible, she says, that the tower was so well defended naturally by its position, that a raised entry (an additional line of defence) was unnecessary. She also points out that a raised entry functioned as a status symbol, since it was the entry used by the chief to access the private rather than the public spaces within the tower. Perhaps Dún an Óir was therefore a lower-status castle, occupied by a garrison rather than by a chieftain. She provides this plan

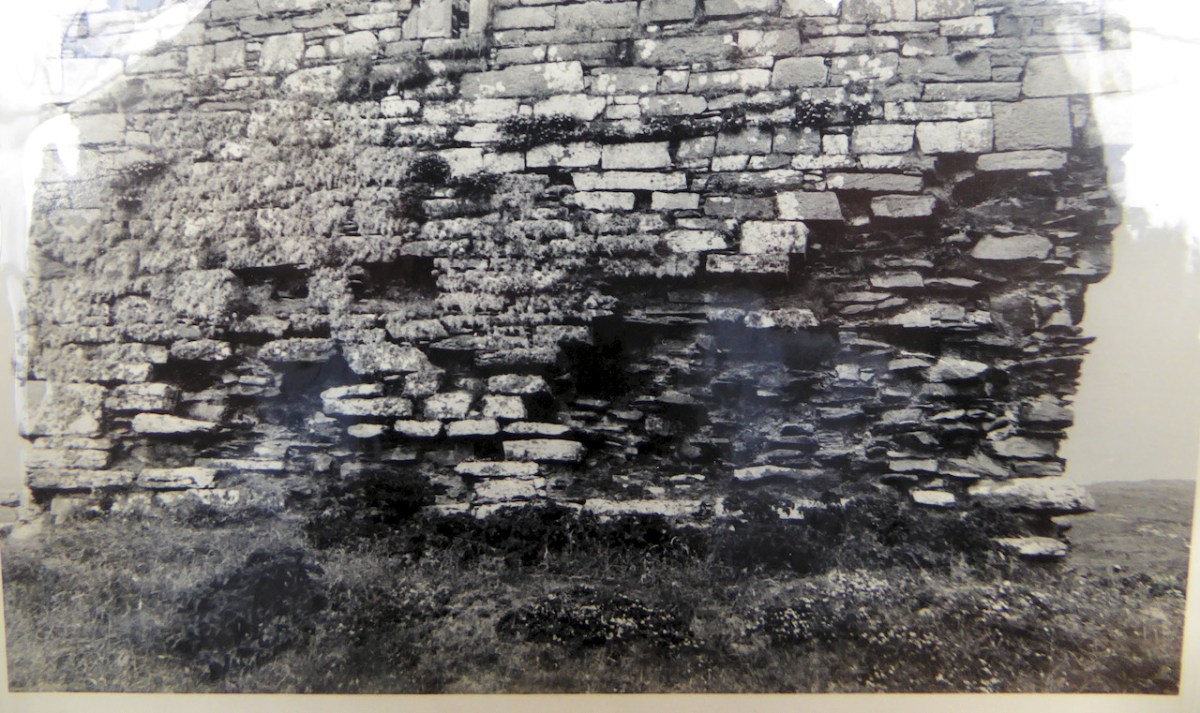

Another unusual feature is the small projecting tower that contained the garderobes. You can see that projecting addition in the plan, above, and in the photograph, below. The entry led up, via a mural staircase to a door giving admittance to the first floor, and carrying on to entries at the second and third floor levels. From there, another stairs led up to the wall walk.

Flat slabs were used to dress the outside of the walls, the same construction method as at Dunlough, although not as finely built.

Instead of a complete vault, such as we see at Dunmanus or Rincolisky, there is a ‘partial vault’, described by Samuel:

Two free arches resembling ‘slices’ of a barrel vault were built. The gaps between the arches and the walls created were lintelled over with large overlapping slabs. This ‘economy’ vaulting was much lighter than a complete vault.

The Tower Houses of West Cork by Mark Samuel

In fact, this type of internal vaulting is not that unusual in West Cork – we saw it at Dunlough and in the small tower at Dunworley. At Dunlough, we can still see many of the large slabs of slate that once bridged the gaps between the arches of the partial vaulting, while at Dunworley the roof is still intact. In Tash’s photograph below you can see the double arches and the full extent of the three floors below them, as well as the chamber above which would have had a pitched wooden roof..

The top room, or chamber, was very high with a pitched roof supported at each end with an archway. The archway also allowed the top of the wall to be kept clear to form a wall walk. A conjectural reconstruction drawing at Ballinacarriga conveys the idea, although Dún an Óir only had one arch, not two.

The battlements have disappeared – they were likely Irish crenellations consisting of stepped merlins and crenels (see here) – but the wall walk can still be discerned. As you can see below, the steps can still be climbed by those brave enough.

Quite a bit of the bawn wall survives, although of course it would have been much higher (possibly as described here). If the sheer cliffs were not enough to deter any thought of attack, the walls would have provided an additional barrier. Unfortunately, they were not able to withstand cannon fire, let alone the passage of hundreds of years. Sarah Kerr has an interesting take on this wall:

Bawns are often considered an additional defensive feature, or at least deterrent. Dún an Óir’s in this regard is somewhat excessive as anyone who could scale the rocky façade of the promontory would likely not be deterred by additional few metres of wall. The bawn, however, would have provided the inhabitants a layer of safety against accidental falls and protection from some of the inclement weather, such as high winds and storm waves from which Roaringwater Bay gets its name. These humdrum practicalities of the medieval lived experience have often been overlooked in castleology or castle-adjacent buildings archaeology, however, it is this very granularity which deepens our understanding of how these buildings worked.

Networked Control: Tower Houses in Ireland by Sarah Kerr

The bawn, in Samuel’s estimation, (that’s his plan above) was big enough to accommodate quite a large herd of cattle. An interesting feature is that of an outside kitchen with an oven, reminding me of what was uncovered at Rincolisky, another O’Driscoll castle, in recent excavations. In the plan above the oven is the circular feature at the north corner of the tower. Other buildings stood inside the bawn, although their purpose is not clear. There may have been a gatehouse, and the ‘possible wall embrasure’ in Kerr’s plan is viewed by Samuel as a corner turret. Samuel lays out what he can interpret of the various walls that surround the castle:

The continuous and well-preserved north wall of the bawn terminates to the west with a return that runs a short distance north before being broken away. This is the inner face, a turret with gunloops which defended the bawn. The curved outer wall enfiladed the mainland with three widely splayed gunloops.

The interpretation of the ruins east of the tower house is more difficult. Erosion has removed the eastermost part of the defences. Two separate walls on the east side of the tower diverge from its orientation; running approximately due east they seem to have formed the north and south walls of a smaller enclosure containing another building. At the west end, the north wall meets a wall (the junction is destroyed) with a gate which abuts the north face of the tower. The robbed jambs of a large gate survive on the east face of the wall and indicates that the gate swung inwards to the west where another enclosure presumably existed. A deep drawbeam is visible in the south jamb. This gate now leads almost directly into a deep ravine. A fair-weather landing stage may have once existed on this side of the island but it would have rarely have been safe to use.

.

The Tower Houses of West Cork by Mark Samuel

Sarah Kerr positions Dún an Óir in a network of O’Driscoll castles that together worked to control the resources of Roaringwater Bay, to levy fishery dues, monitor trade, and defend territory when necessary. Within this network, the highest status tower, and probably centre of administration was Dún na Séad (Baltimore). The highly visible nature of all these castles, some on promontories and all visible from the sea, were ‘manifestations of authority, wealth and status.’ She posits that:

Due to Dún an Óir’s lack of a slipway, natural harbour or rock-cut steps, it is unlikely that manging the fish produce was a primary role at this dwelling, particularly as Dún na Long and Dún na Séad were more suited to such tasks. Instead Dún an Óir probably managed the victualing and collection of fees from passing ships, indicating that the tower houses worked in unison. It appears that each tower house had a specific role which complemented one another, as such they were unique actors that performed as a network

Networked Control: Tower Houses in Ireland by Sarah Kerr

It’s surprising how much we can tell from the remains of this once prominent symbol of power. It will never be on a tourist trail and I would not advise anyone to try to access it – but as you can see, Tash and his group managed it.

In response to my first post I had several suggestions for alternate titles on Facebook. Ruamann Ua Ríagáin proposed an alternate interpretation as Dún an Ár, or Fort of the Slaughter. There are no indications that there was any tradition of cattle-slaughtering at this site, nor any record of a massacre. However, it remains a possible interpretation. Another reader, Tom Driscoll found another Dún an Óir which was assumed to come from Dún an Ochair, meaning Fort on the Brink/ Cliff Edge. Certainly apt for this location. Finally, note the long comment on Part 1 by OVERSEASGREATGRANNY who is trying to trace similarly named forts and relate them to Irish history – quite fascinating.

When the storms rage over Roaringwater Bay it is natural to wonder how long this castle can last, isolated on its spit of land and open to the full force of nature. But it is also a comfort to know that the castle builders built it so well that it has lasted now since it was built around 1450 and battered in 1601. Here’s to another few hundred years!