This week I experienced, in Virtual Reality, what is was to belong to a Flying Column during the Irish War of Independence. With the men, I crawled through a West Cork field, gun at the ready, alert for any sign of the British army or the Black and Tans.

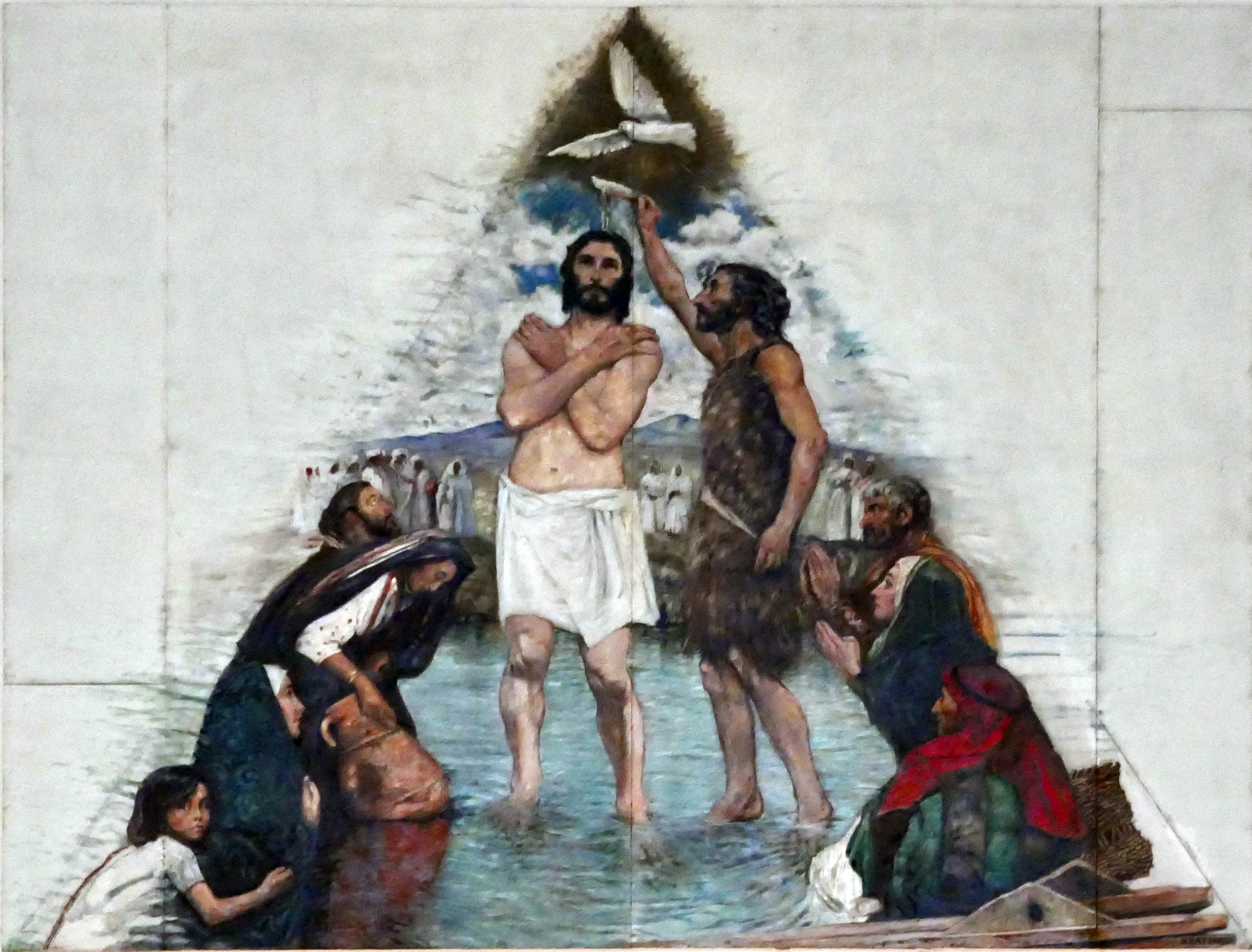

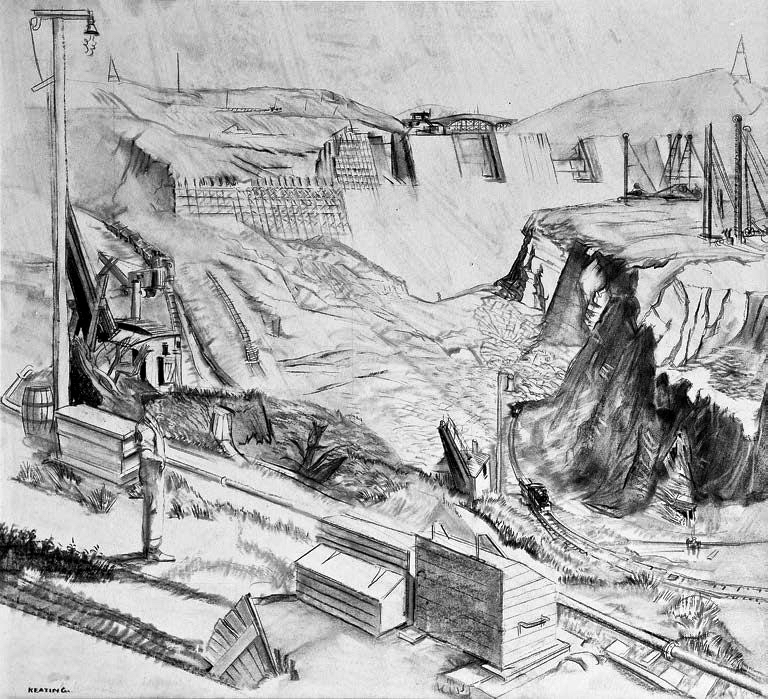

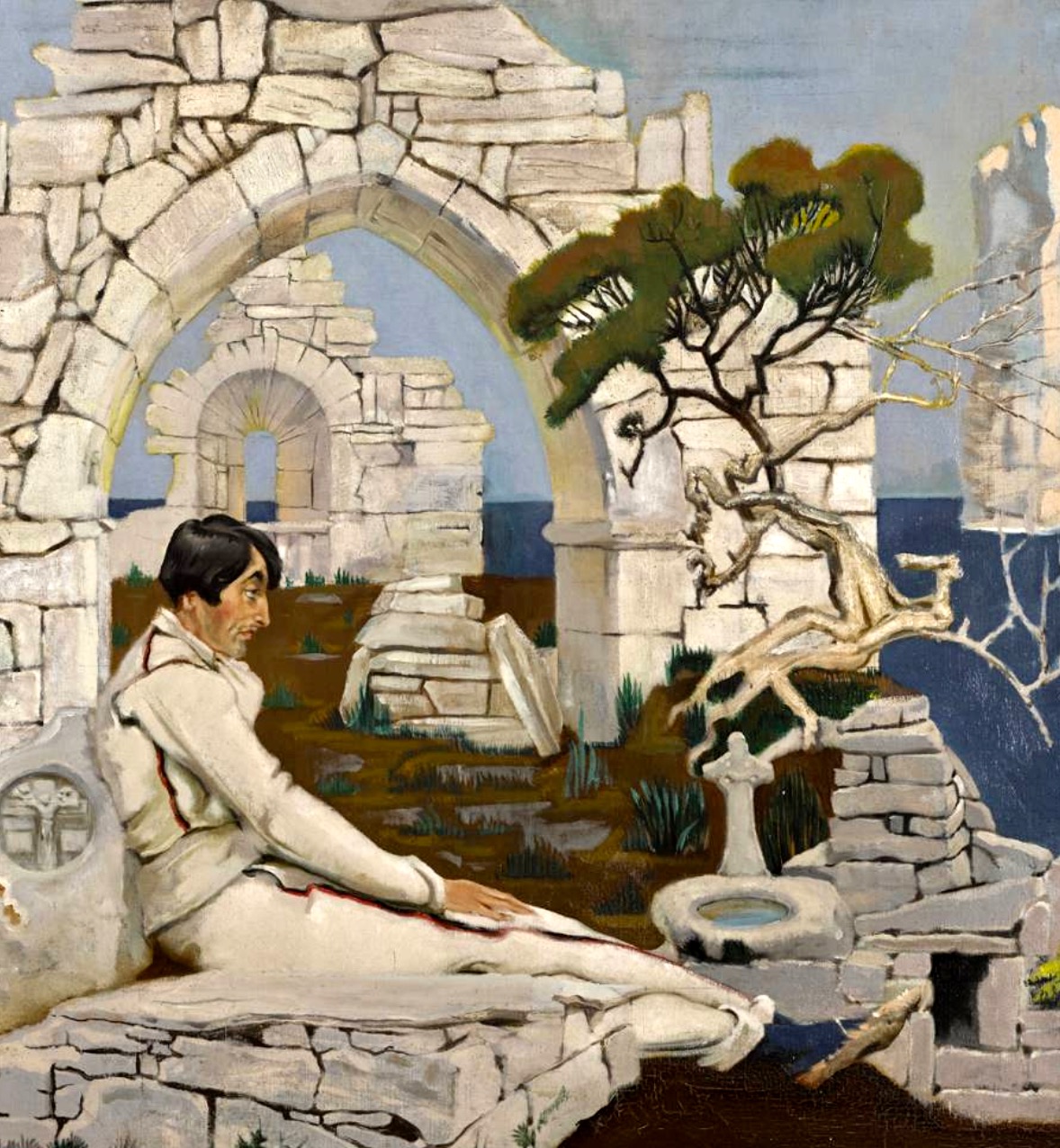

Or, at least, that’s what it felt like, and I must admit to a slight pounding of the heart as we were crouched behind that stone wall. In reality, I was on a swivel chair in the old Uillinn coffee shop, now repurposed as a VR theatre, wearing a VR headset. The Sean Keating painting that this experience is based on is the iconic Men of the South and you can read all about it here.

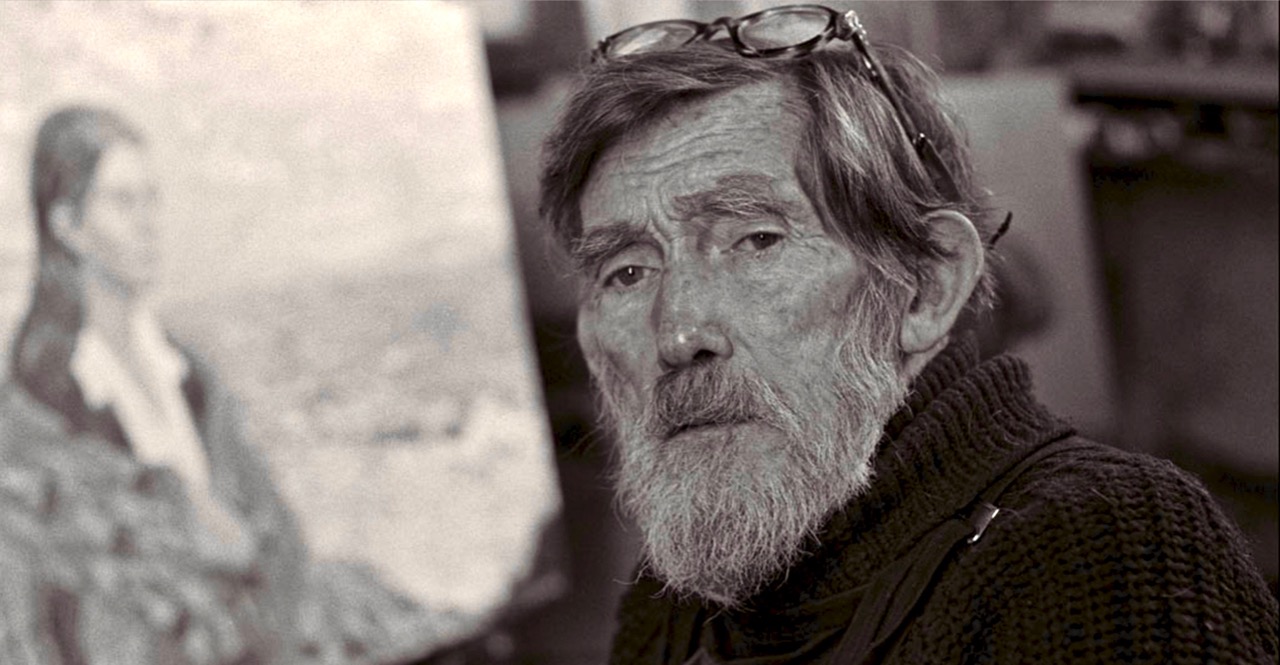

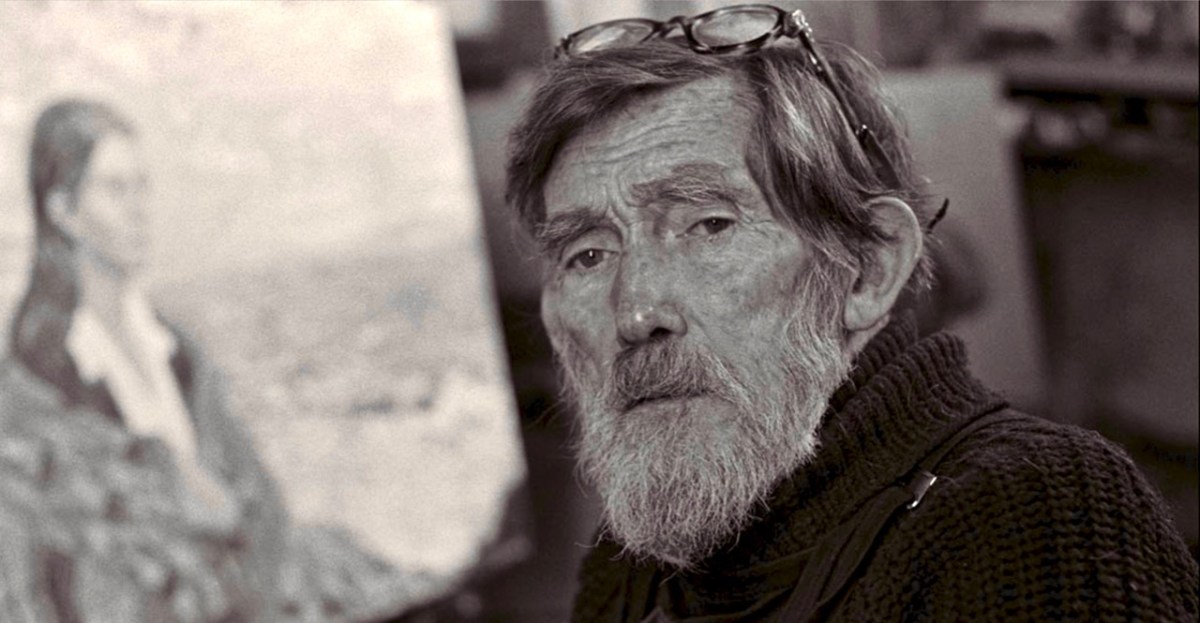

Keating’s grandson, David Keating, and his creative partner Linda Curtin, have produced the VR experience, shooting it in West Cork in “360 stereoscopic + volumetric capture” with the help of many local people and the new West Cork Film Studio. Dr Éimear O’Connor provided the expert consultations on Sean Keating (below) and features, amusingly, as an exasperated director of the action. If you get a chance to see this anywhere, grab it! You can also read more about Sean Keating in this post by Robert from 2020.

And this War of Independence action leads nicely into Kathleen O’Connell. You will remember her as one of the heroines of Karen Minihan’s book More Extraordinary Ordinary Women. Take a quick trip back to this post and read all about her and her daring and courageous deeds. I concluded this section by saying

Kathleen was ruined financially by all her support for the cause. Letters of support for her pension application were fulsome in praise of her work and her commitment. She was awarded a grade E pension in 1939. She died, here in 1945, aged 50. She had not married and had no children, and all memory of her gradually disappeared from Ballydehob. When Karen went looking for the house she had lived in, it seemed nobody could remember the heroic Kathleen O’Connell who had once lived here.

How wrong we were! Memory of Kathleen was far from dead. A relative of hers recently contacted Karen and on Friday afternoon we spent several hours with him and his charming grandson, rediscovering Kathleen from a man in whose family her memory was still fully alive. (He didn’t want his photo in the blog post, although Neven, the grandson, was happy to be in it.)

The first thing he showed us was her grave, at the historic Abbey Graveyard in Bantry. It contained many family members, including Kathleen. Our guide had knowledge of everyone in the grave and how they were related, and told us that there were probably more people in the plot than commemorated on the headstone. The grave looks out over the sea at Bantry.

Next, he brought us to the cabin belonging to her Uncle Pat where she sheltered men on the run. It’s located in the hills behind Ballydehob, down several lonely boreens and across a couple of (very muddy) fields. The cabin, now roofless, still stands and still has the wonderful oak mantle across the open fireplace.

We marvelled that Kathleen was doing all this on her bicycle – it’s several kilometres above Ballydehob and about 100 metres above sea level. And of course few of the roads would have been paved at that time. Our guide told us that she was totally and passionately committed to the cause, and that, since she was an only child, she carried her parents along with her. It was really they who underwrote all the expenses she incurred in her work.

In the family, it was understood that she had been engaged to a man who was a member of a Flying Column – just like one of the Men of the South, but that he had been shot. We could only wonder at the trauma and distress she had experienced. She left for America in 1925, but returned to live in Ballydehob, and her father eventually outlived her.

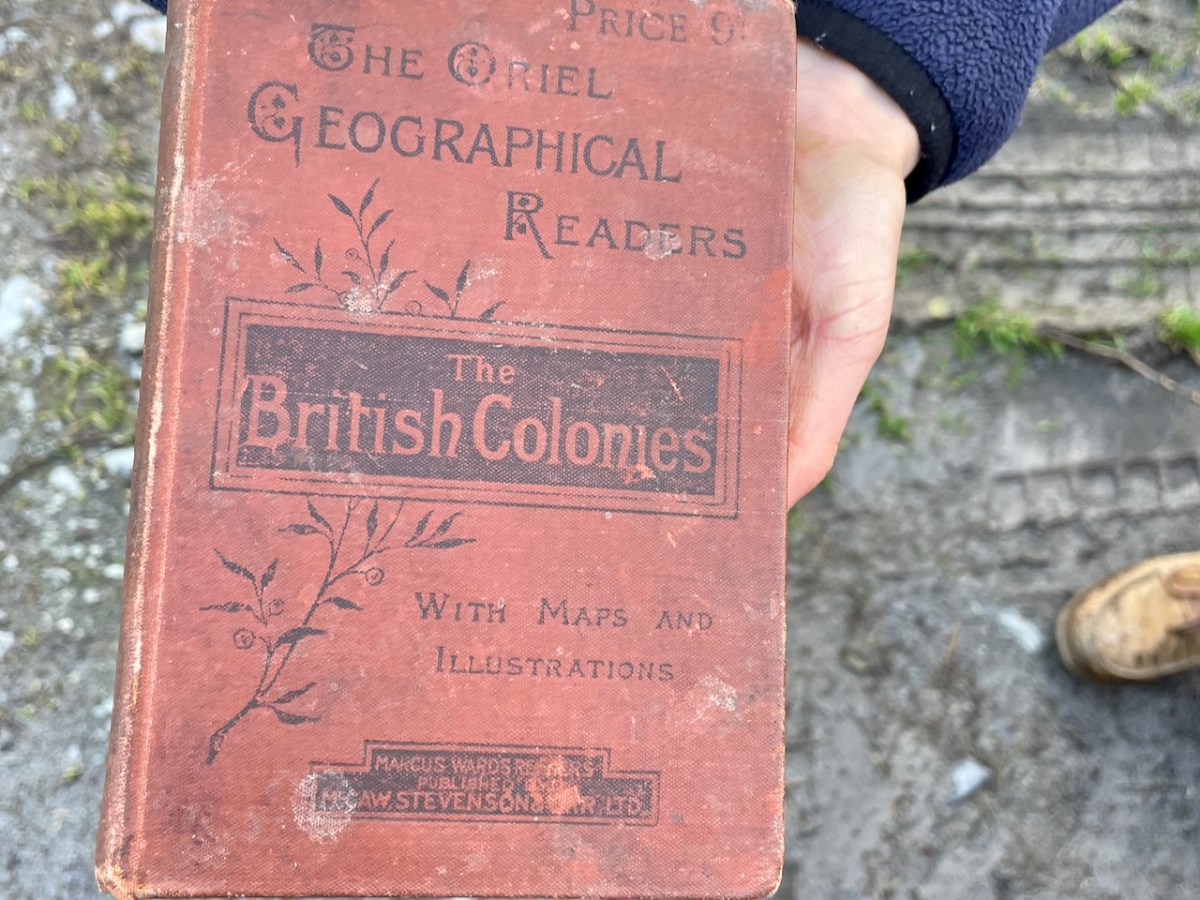

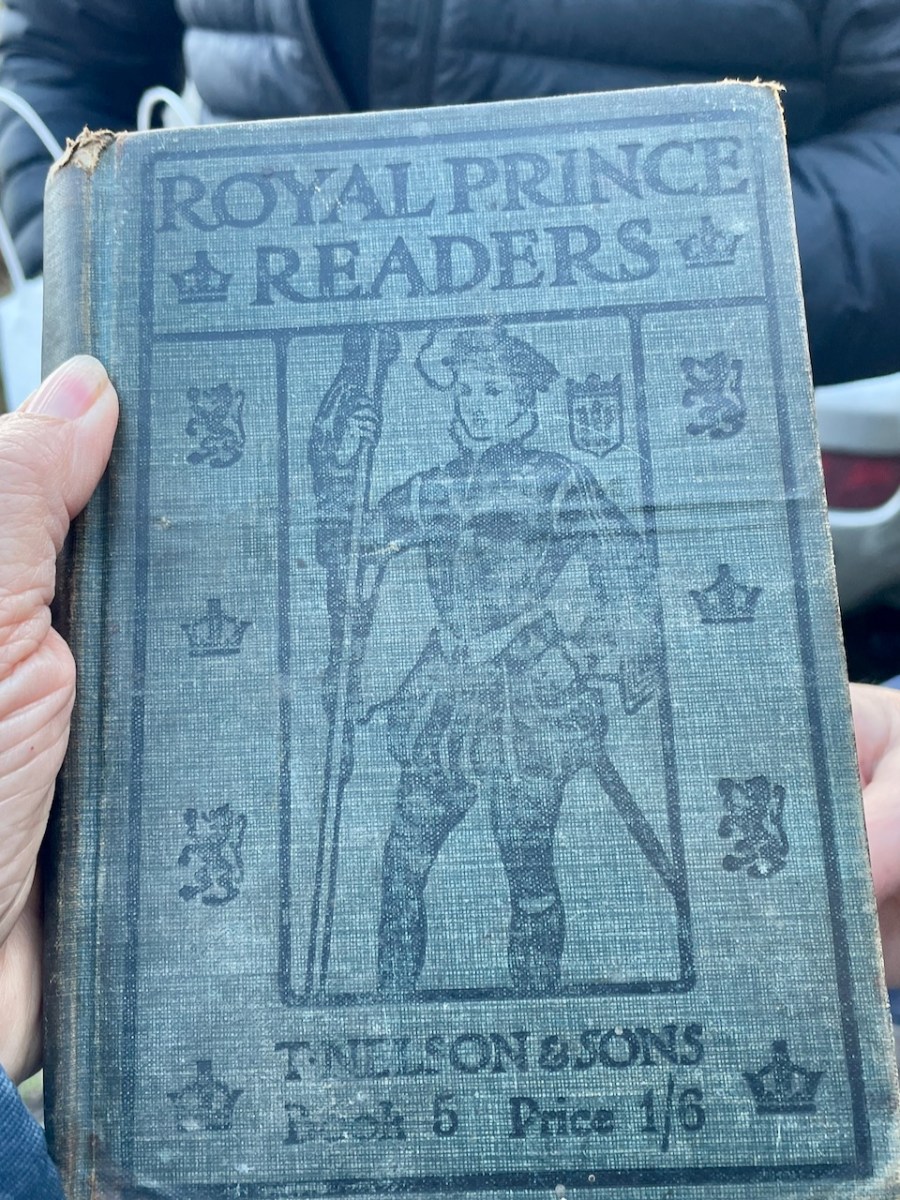

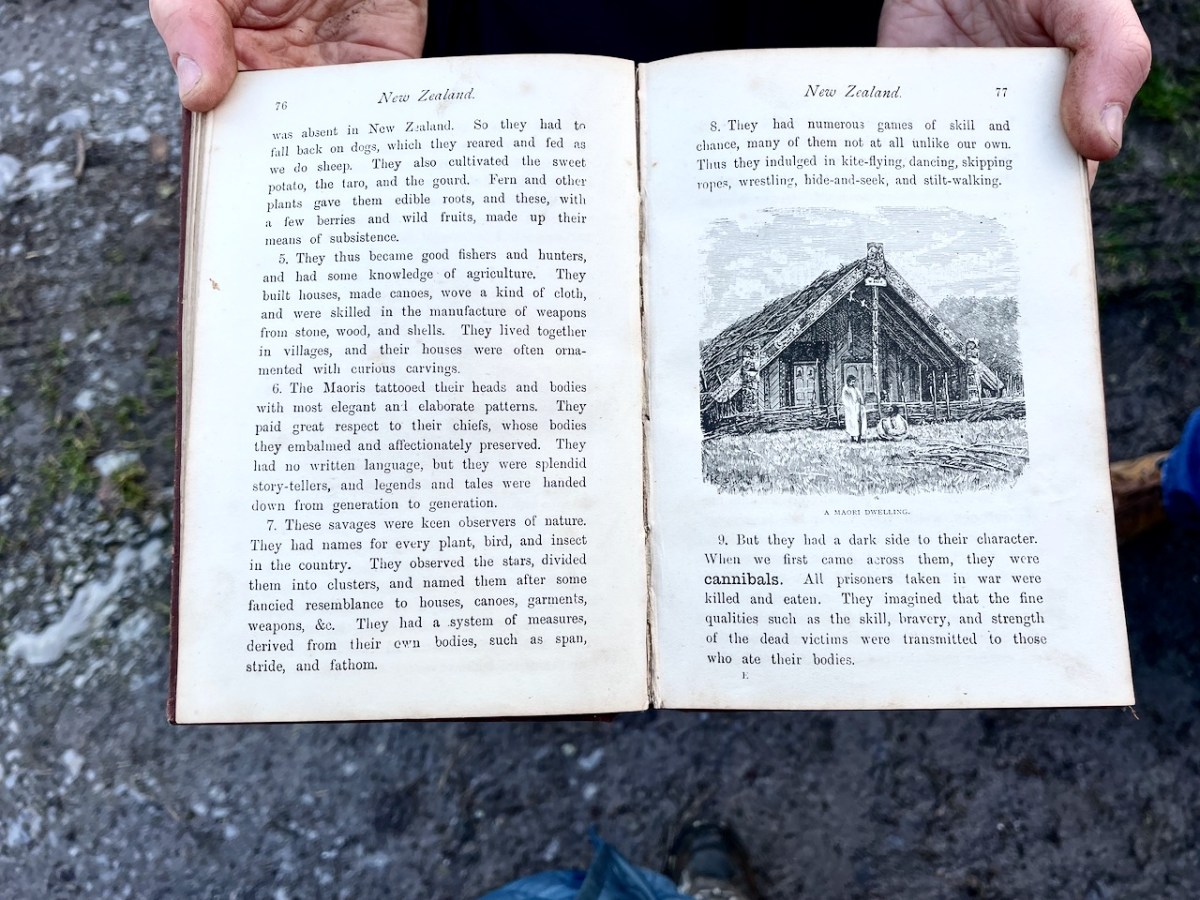

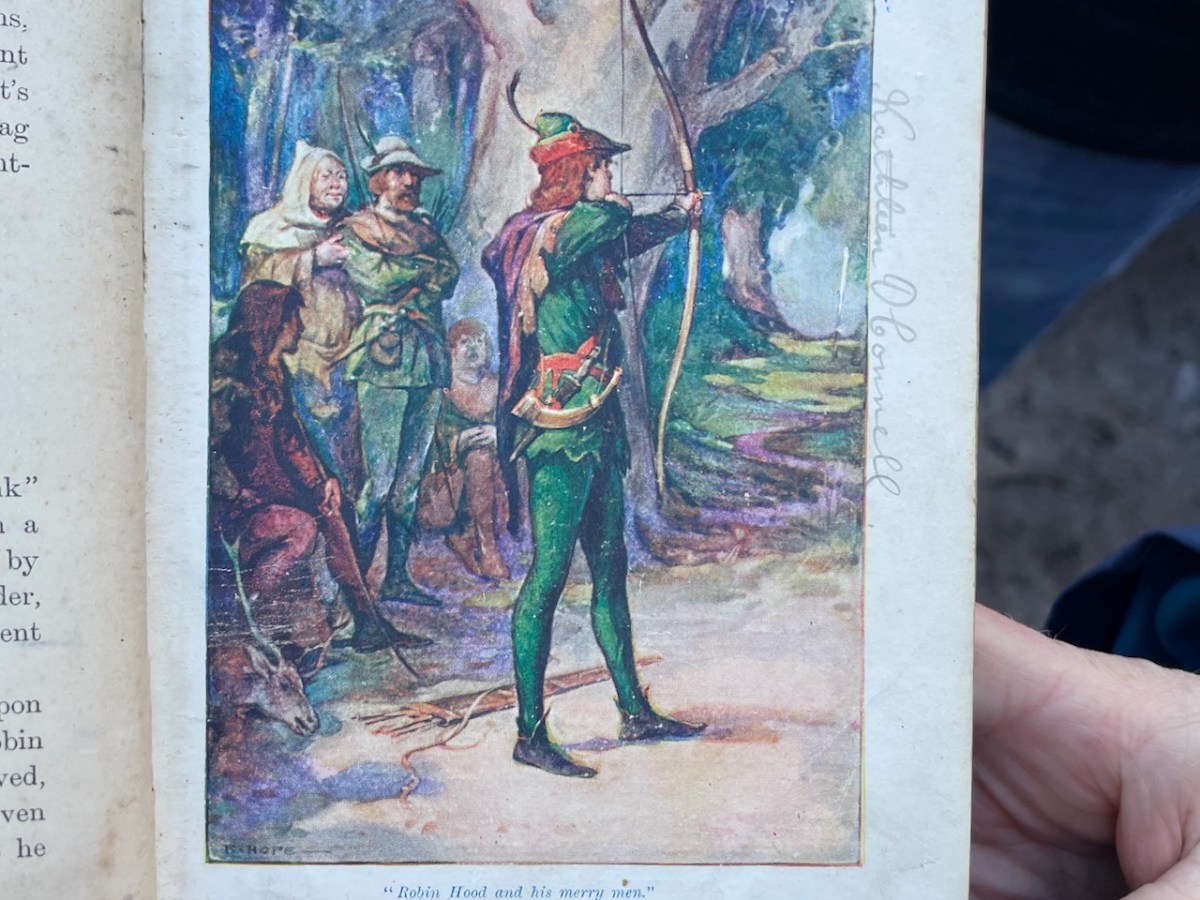

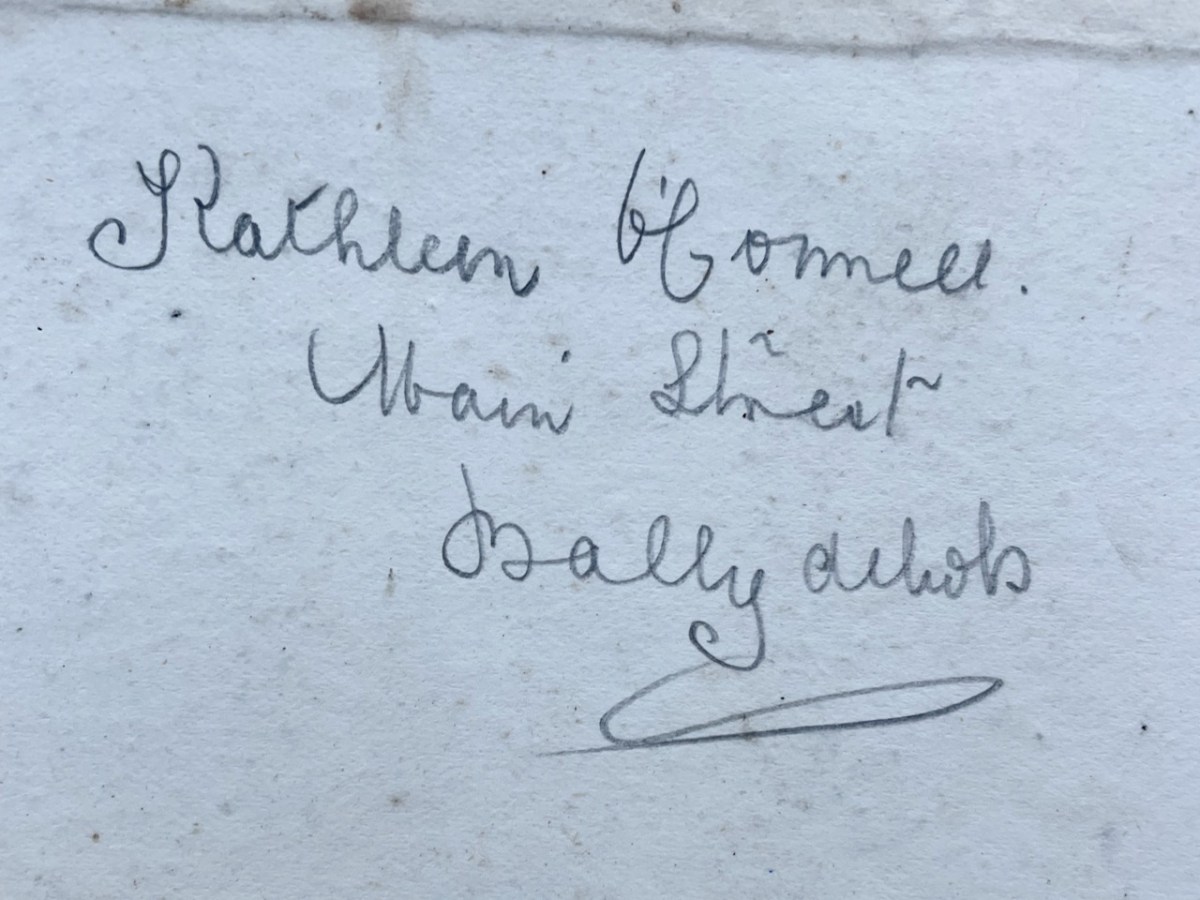

Our final mementoes of Kathleen were particularly poignant. Surviving in the family were two of her books, school books we think, in which she had written her name.

Each was very British – a reminder to us all what the standard school fare was at the time when we were members of the British Empire.

I have located a copy of the Royal Prince Reader (1910) on EBay – in Rajastan! A further reminder that empire was promoted through children’s literature as much as through military occupation.

Somehow these two books, her own possessions, brought Kathleen to life as nothing else could have done. We imagined her devouring these stories in school, and her gradual disillusion as she matured with what the Empire stood for.

It is an immense comfort to know that she is not forgotten after all.