As promised this will be a skip and a hop over Vols 4 and 5, as this is my last post and I want to leave time for a final evaluation of Vallancey and his work. I’m just going to pick out items that caught my attention or appealed to me for my own quirky reasons. For everything I write about, there will be a dozen that might appeal to you more. But then, as a friend of mine said recently about an interminable novel – we’ll be reading it at your funeral.

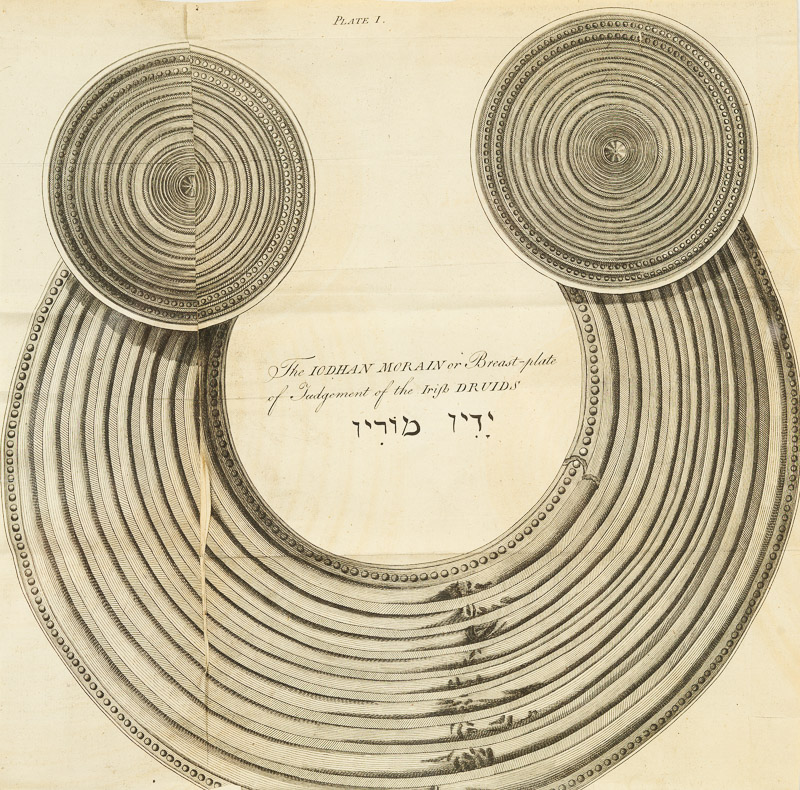

After his usual lengthy preface (this one is only 60 pages and yet another opportunity to talk about Phoenicians) we come to a series of short articles about archaeological objects. Below is what archaeologists call a gorget – its a gold collar, beautifully worked. There are fewer than a dozen of them known from Irish contexts and they have some parallels with others found on the continent.

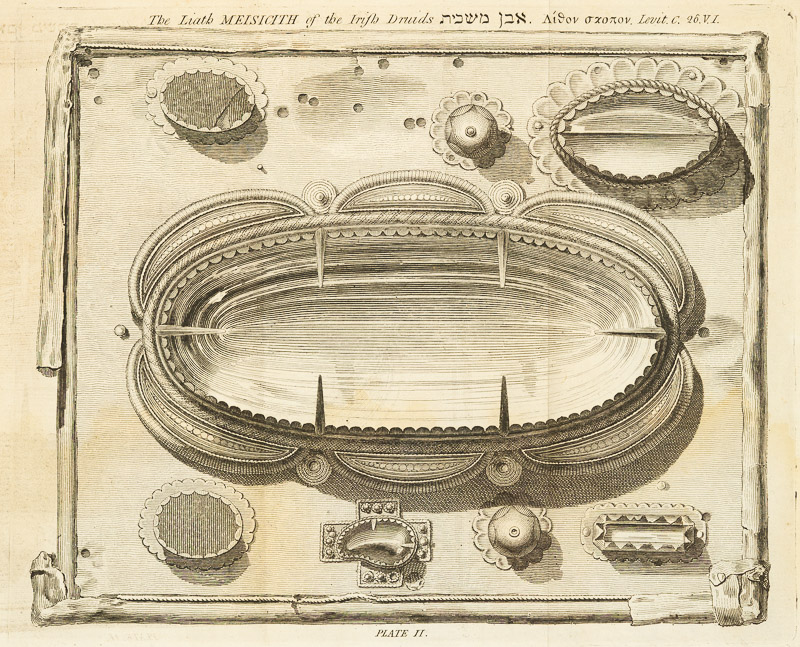

Of solid gold, they were heavy and obviously made to be worn by a high-status individual, perhaps a king. Vallancey concludes it is a Druid’s (what else?) breast plate and christens it the Iodhan Morain. He comes to this conclusion by examining the Bible and accounts from ‘the Chaldees’. It is to be worn, he asserts, as the Druids are making their most solemn pronouncements. And while he’s on the subject of druids, here’s another one of his evidence-free assignment of purpose. This is what he calls the Liath Meisicith.

It is a box, the size of the drawing, and two inches deep, it is made of brass cased with silver : it contains a number of loose sheets of vellum, on which are written extracts of the gospel and prayers for the sick, in the Latin language, and in the Irish character. There are also, some drawings in water colours of the apostles, not ill executed : these are supposed to be the work of Saint Moling, the patron of that part of the country.

So – a fairly straightforward conclusion might be reached that this box dates from the medieval period and was some kind of Christian votive object, right? Alas no – for Vallancey sees only the absence of a cross or any other Christian symbol, and concludes that this is for containing incense or oil to be used as part of a druidic fire ceremony.

How this fire was communicated, I cannot pretend to say, but, as it is well known, that Cobalt ground up with oil, will lye an hour or more in that unctious state and then burst into an amazing blaze : it is probable that the Druids, who were skilled chimysts, (for their days) could not be ignorant of so simple an experiment. A fire lying so long concealed, would afford them ample time for prayers and incantations.

I think this one example gives you, as a microcosm of the whole Collectanea, how eagerness to embrace an exotic and far-fetched explanation, and shoehorn it into your overall theory, can get the better of a man. And it was this exact kind of thing that led to him being derided by his contemporaries and those who followed.

A final example, as it is meaningful to me – a little reliquary figure comes next. This figure bears a striking resemblance to one of the figures on St Manchan’s Shrine. One of the missing figures was located and returned to it – it’s known as the 11th figure and it’s on the far left, below.

Could this be a 12th – and what has happened to it? We know it was still extant when our old friend George Victor du Noyer was recording archaeological items – here is his sketch of the same one as in Vallancey’s volume, done in 1837.

I put the question to Dr Griffin Murray, author of the superb book on St Manchan’s Shrine and he told me that this one was known as the Beard Puller, that is was from Co Roscommon and was in the Trinity College Museum, but is now lost. It could definitely be from St Manchan’s the shrine, he says, although equally it could be from another one. Why is this little guy meaningful to me? Well, I subscribed to the publication of the book, and a reproduction of the 11th figure was my reward!

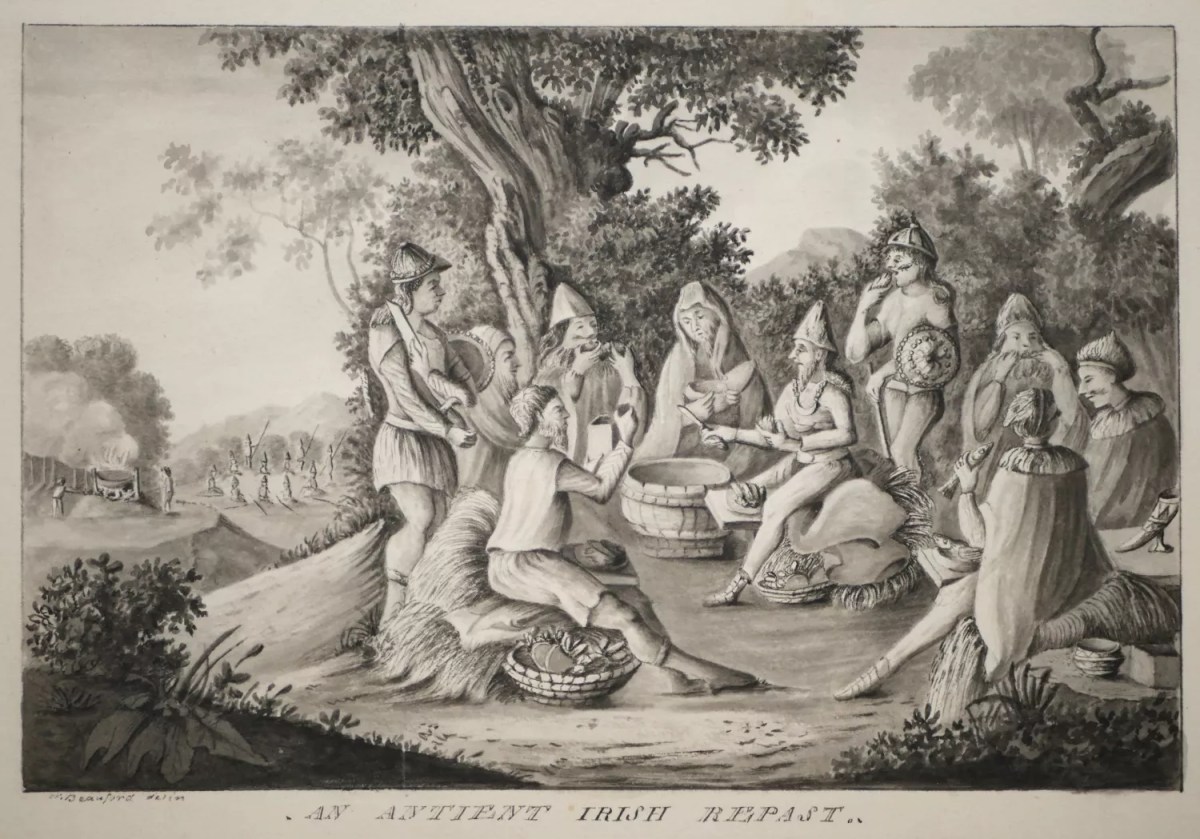

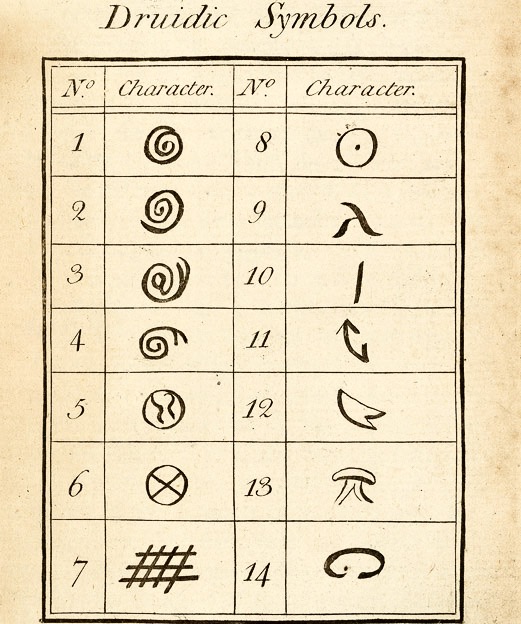

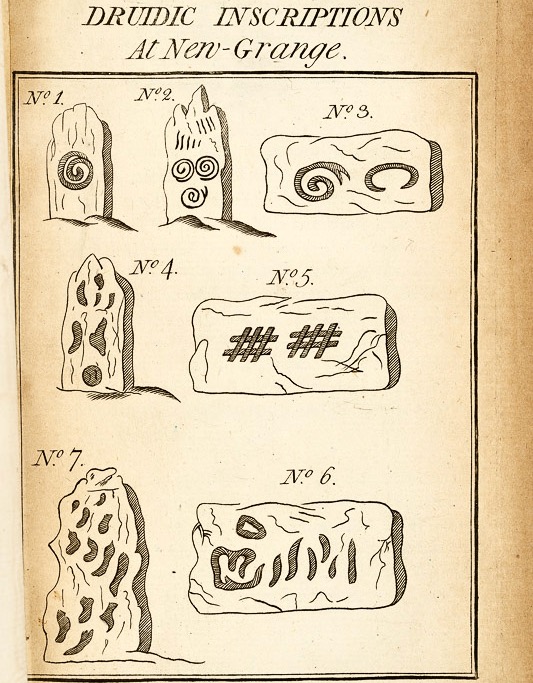

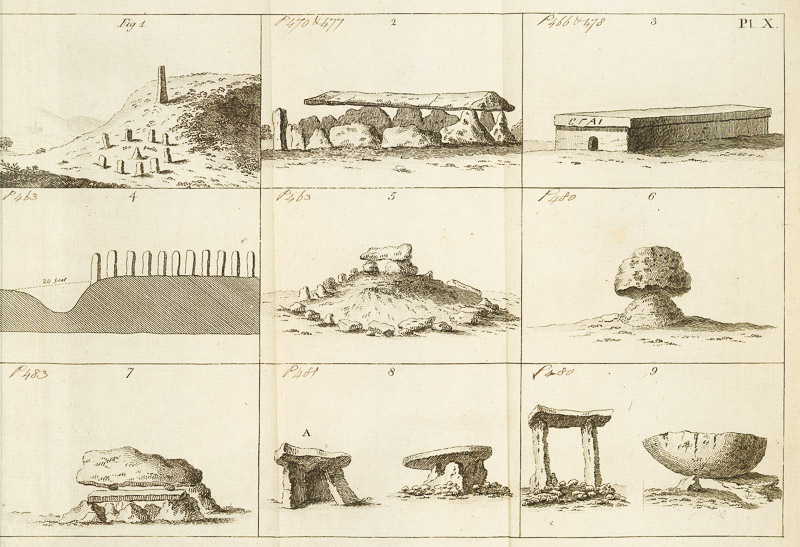

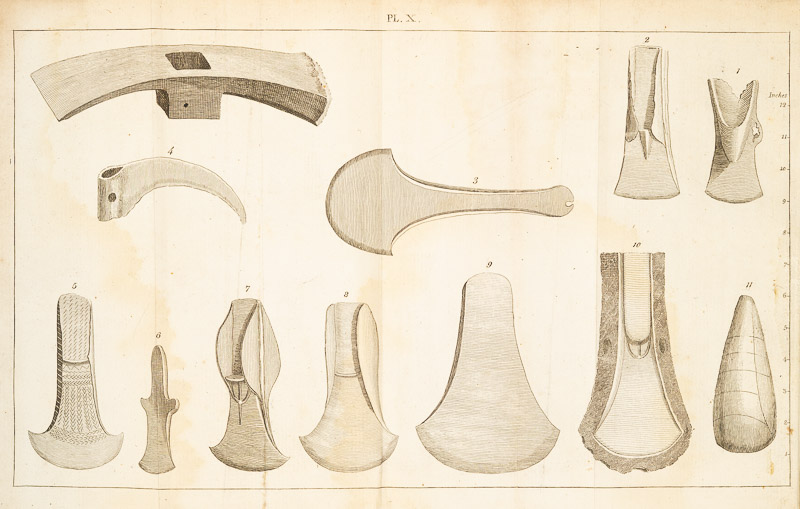

This section contains important illustrations of prehistoric objects – important because this was the first publication to bring them to the notice of the general public. I will use some of these to illustrate the rest of this post, so look out – they will not all relate to the text around them..

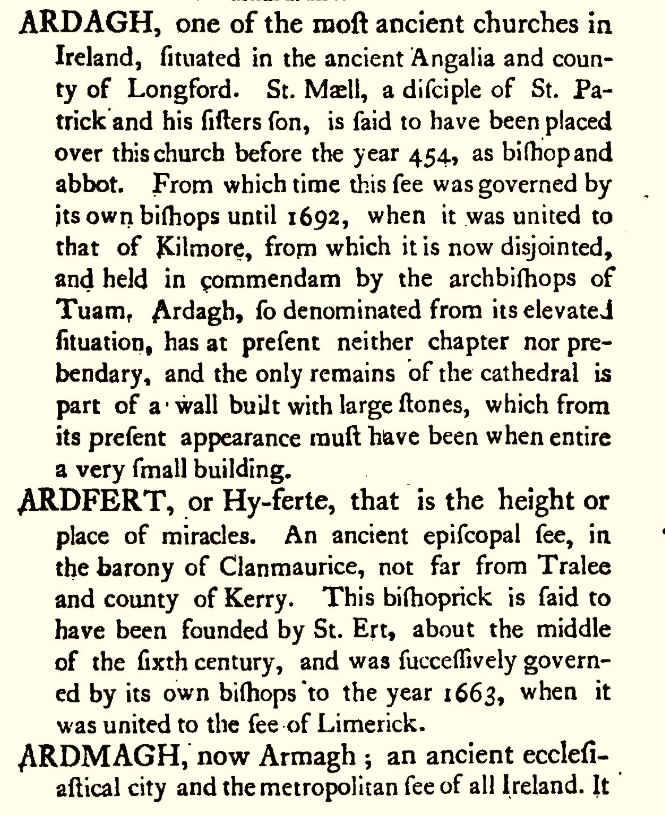

However, I am going to skip down now to a section called Proposals for collecting materials for publishing the ancient and present state of the several counties of Ireland. This is an significant section in that it lays out the need for actual knowledge of the country of Ireland, including its natural assets – air, water, geology, animals – and man-made such as buildings, charities, manufactures, and antiquities.

Vallancey lays out the questions to be answered. It all seems so elementary, doesn’t it – and that’s what is so staggering, that there could have been so little in-depth knowledge of the actual country at that time. You might remember that we read about one of these county surveys for Westmeath in Vol 1. What a wealth of detail we might now have of life in 18th century Ireland if only this had been accomplished as Vallancey described it. My friend Amanda, of Holy Wells fame, would be particularly grateful!

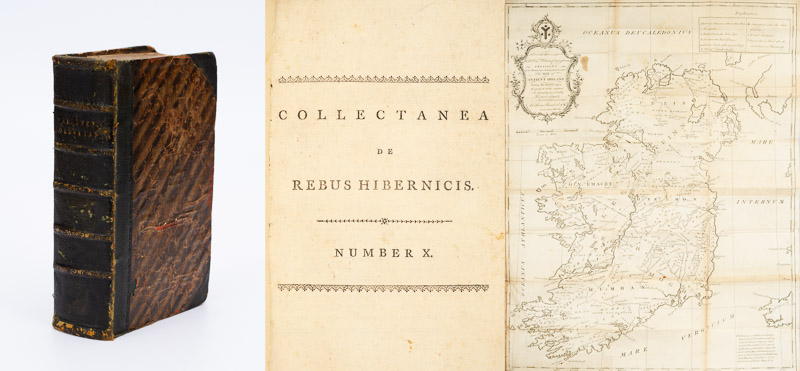

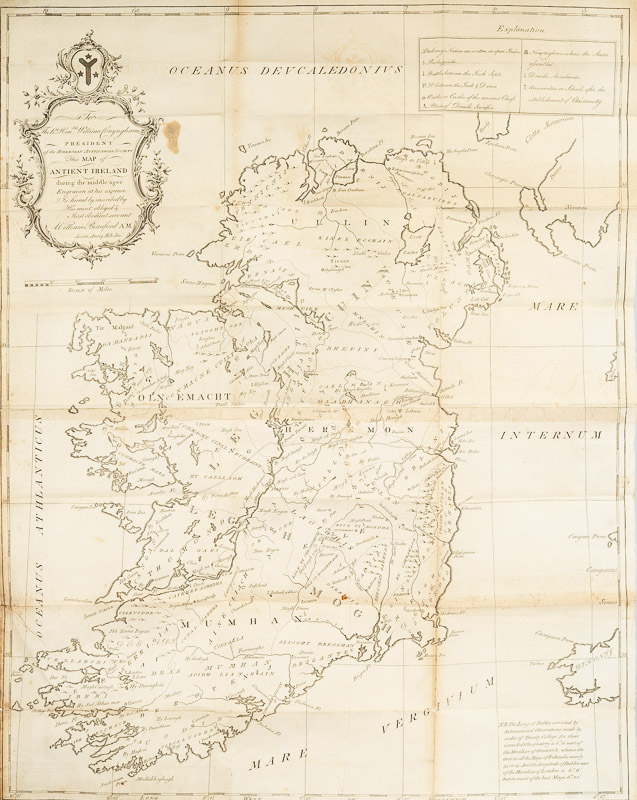

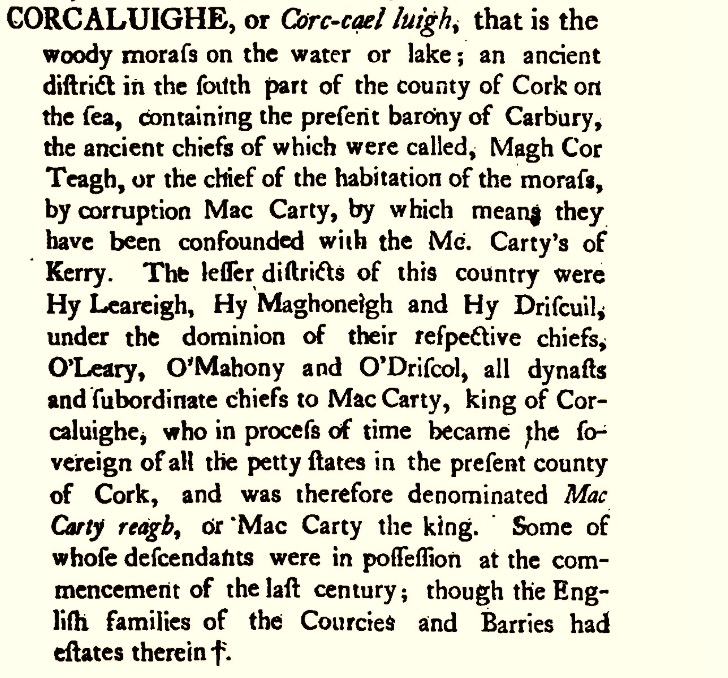

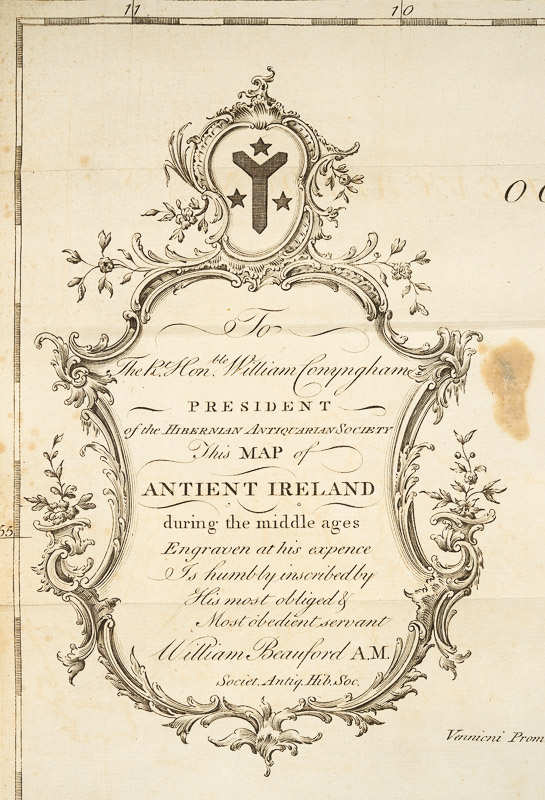

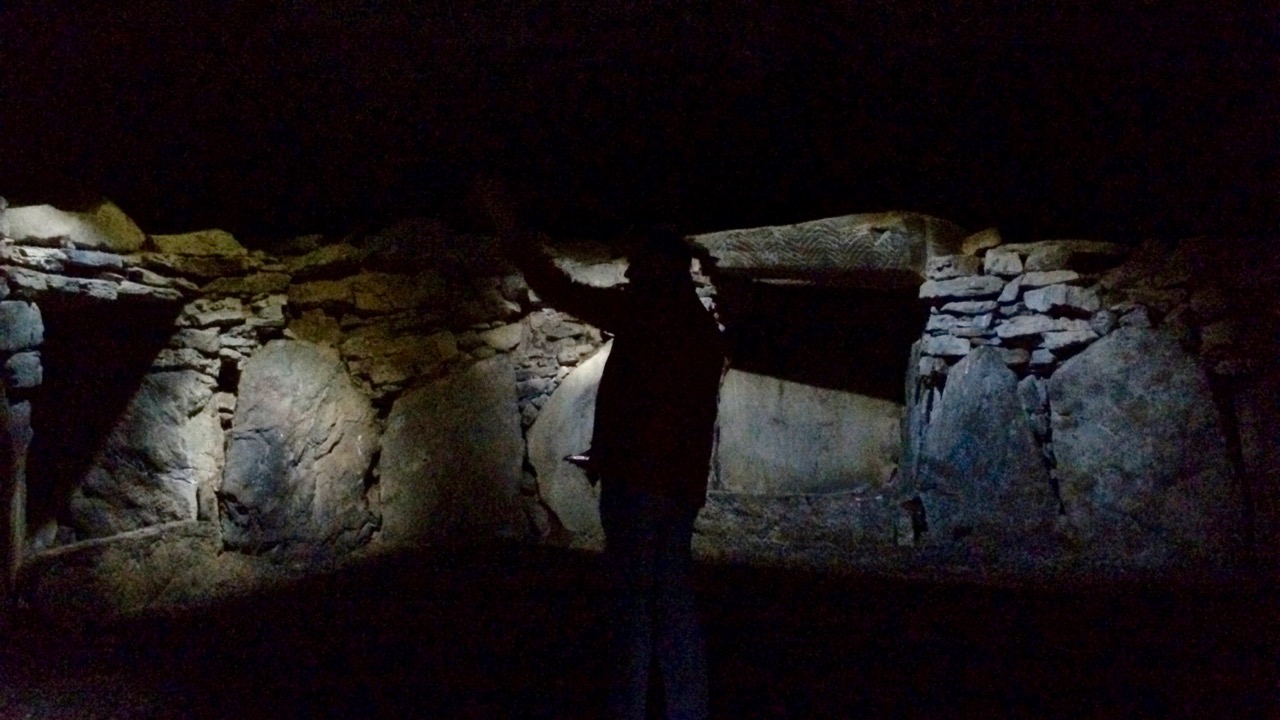

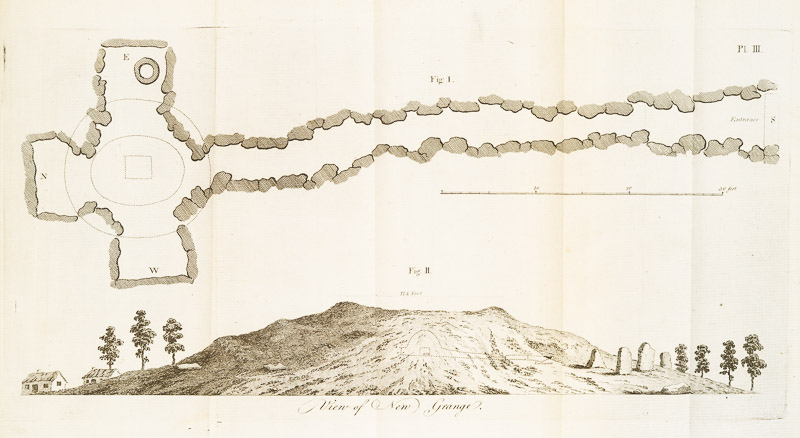

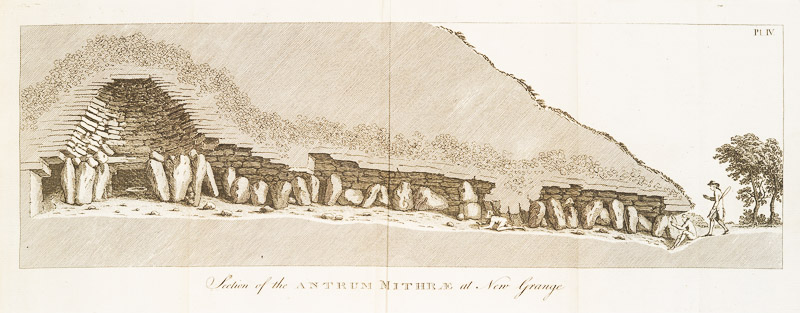

The rest of this volume is taken up with A Vindication of the Antient History of Ireland, with lots of Vallancey’s pet theories on display. It contains a really excellent plan and section of Newgrange – a truly outstanding piece of mapping, given the fanciful nature of most drawing of prehistoric monuments of the time. His conclusion about Newgrange, that it was a Mithratic Fire Cave, turned out be in fact not so far-fetched as some of his other notions, given what we now know about the winter solstice at Newgrange.

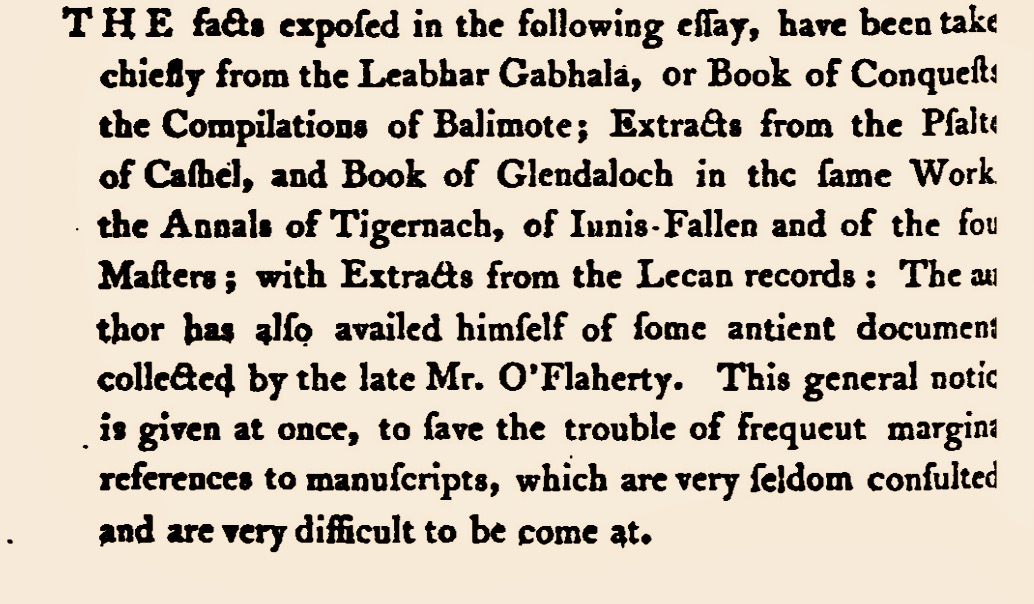

There is also some fascinating stuff about Irish paganism and Irish saints. The sequence is based on the mythological original story for Irish history called the Leabhar Gabhala. It’s a pity to give it such short shrift, but I am determined to press on and so I now pass to Volume 5, which is the last volume in the set. There is a Volume 6, and I can access that online only, so have decided to finish with the last volume I have been able to examine in person.

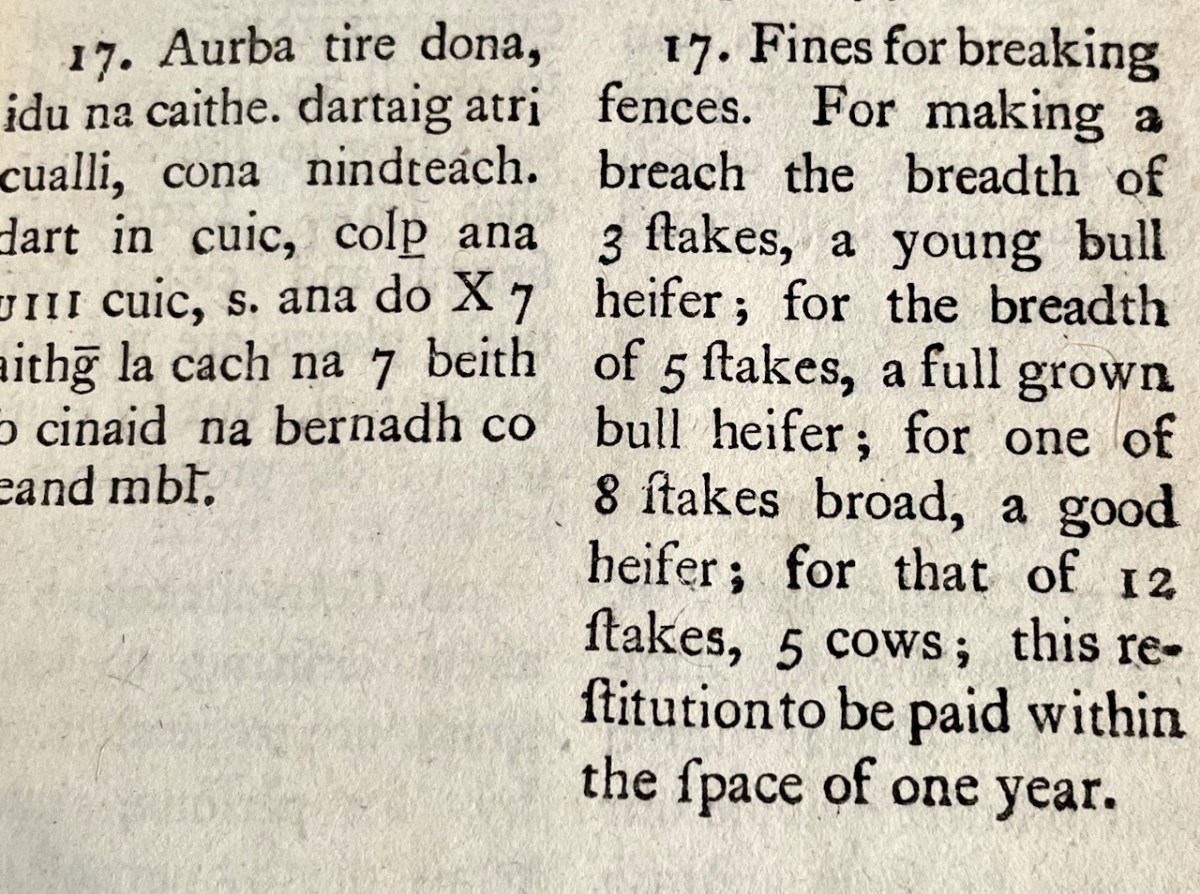

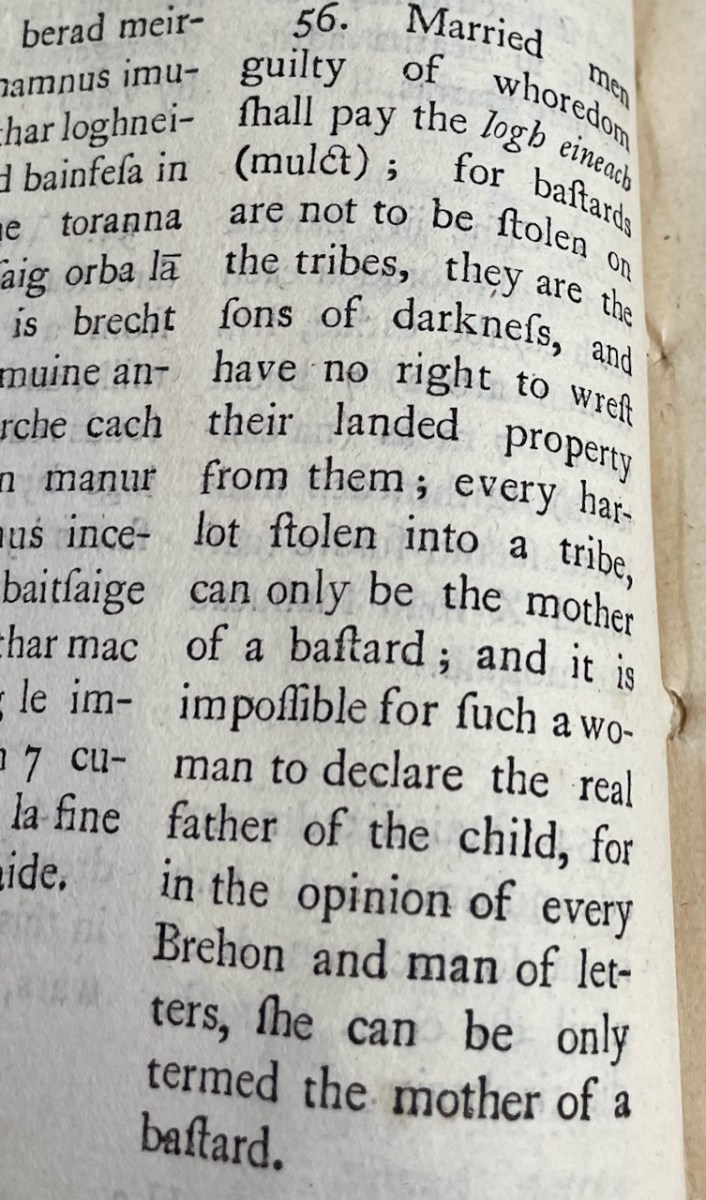

As you can see from the Table of Contents (which, by the way, never seems to be quite the same as the frontispiece that lays out What This Volume Contains), there is a certain amount of repetition here from previous sections on The Scythians, Ogham, the Chaldeans, and the Brehon Laws. So, I am going to confine myself to the part about the Irish Feudal System of Government, as it so well represents what it’s like to read Vallancey.

After a preamble of many, many pages in which are mentioned the Phoenicians, the Egyptians, Aristotle, the Belgae, gold from Wicklow, Alexander the Great, Mr Wilkins (I’m not making this up), Aboul-Hassan-Aly, Armenians, the Empress of Russia (honestly), Father Georgius (who resided long with the Tibetans but who wrote in Latin, quoted at length here), the Huns (we might actually be Indo-Scythian-Huns, apparently), the Japanese, the Peruvians, the Great Mogul, Vallancey, perhaps not surprisingly informs us that the feudal system in Ireland was based on all of the above, except for two things.

The Tuarasdal, wages or subsidies paid annually by the sovereign to his feudatory chiefs, for which he received from them a certain supply of military forces, or some other state contributions tending to the common interest.

The Tribute for Protection. It is called in the Irish laws. . . eneclann, (i. e. protection of the clann). . . It does not appear that these vassals were originally obliged to furnish troops for their chiefs, but to pay a certain impost or tax for their protection.

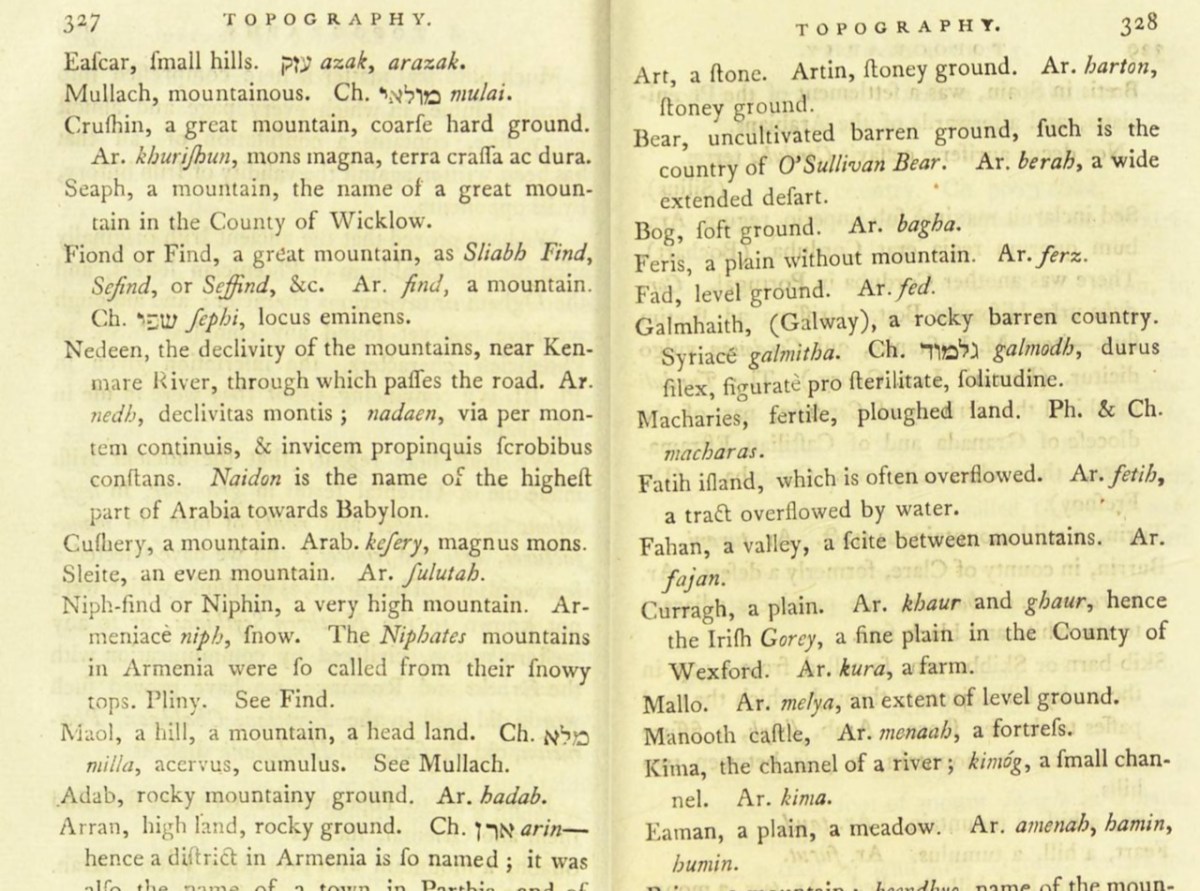

He’s particularly fond of the oriental influences here and to hammer home his point he provided a dictionary of topographical terms all of which he assures us come from Oriental Languages. Some examples, including their Arabian, Hebrew, Chinese, origins, etc:

My head hurts, so this is a good place to stop. How do I sum up this amazing man and his colossal and controversial achievements? The marvellous site Ricorso has a whole section on him which brilliantly sums up the person (although by one authority in here he has acquired 27 children!) and is worth reading in its entirety. The following quotes all come from there. It gives me the new information that Vallancey, despite all claims to the contrary, never actually learned Irish, although he owned a grammatical dictionary compiled by a school-teacher named Crab. One commentator, James Hardiman, confirms this, stating

It is well known, that the late General Vallancey obtained much literary celebrity, both at home and abroad, and, in fact, first acquired the reputation of an Irish scholar, by the collation of Hanno, the Carthaginian’s speech in Plautus. . . but it is not so well known that that speech had been collated many years before, by Teige O’Neachtain, an excellent Irish poet, and author of the extempore epigram, Vol. ii. p. 120, of this collection. Vallancey had this collation in O’Neachtan’s hand-writing, in his possession; and I am obliged (with regret) to add, that he never acknowledged the fact, but assumed the entire credit of the discovery to himself.

Thomas Davis says:

His “Collectanea”, and his discourses in the Royal Irish Academy, of which he was an original member, spread far and wide his oriental theories. He was an amiable and plausible man, but of little learning, little industry [not fair, I think], great boldness, and no scruples [nor this]; and while he certainly stimulated men’s feelings towards Irish antiquities, he has left us a reproducing swarm of falsehood, of which Mr. Petrie has happily begun the destruction. Perhaps nothing gave Vallancey’s follies more popularity than the opposition of the Rev. Edward Ledwich, whose Antiquities of Ireland is a mass of falsehoods, disparaging to the people and the country.

Here’s a good summation, from Joseph Leerssen

The successor of the Select Committee was the Hibernian Antiquarian Society, 1779-83, which in turn set in motion the creation of RIA in 1782, with Vallancey as one of its founding members. Vallancey was the son of a Huguenot émigré, Army officer; derided by many as a charlatan or at best a naive nitwit, Vallancey contributed few ideas of any value to the study of Gaelic antiquity, but much badly-needed enthusiasm, energy and social/religious respectability. He had founded his periodical Collectanea de rebus Hibernicis as a forum for antiquarianism. Further, it was the additional merit of Vallancey to open this world [of Ascendancy] enthusiasm for Irish antiquity] to his friend and mentor Charles O’Conor, in whose wake younger Gaelic, Catholic scholars like O’Halloran and Theophilus Flanagan could begin to function in close collaboration with Ascendancy Protestants.

So what have I concluded after lo these many weeks of sitting with Vallancey? The first is that it was a wonderful experience to be able to read the five volumes ‘in the flesh.’ The second was the whole things gave me a unique insight into the origins of my own discipline of Irish archaeology – how it was born out of a cauldron of claim and counter-claim, hubris and argument, ideology and fieldwork, nationalism and orientalism. None of that can be understood and appreciated without the towering, if ultimately misguided, figure of Charles Vallancey. Thank you, Holger of Inanna Rare Books, for this opportunity.