There are a thousand ways to tell a story. I thought I had written up much of what’s to know about the coming of Electricity to the rural areas of Ireland in this series (click the link). However, I now realise I have missed a dimension in this recounting: I haven’t included the direct experience of the populations whose lives were upturned by this state-imposed revolution. I haven’t written about that – but someone else has!!

Our very good friend Amanda – she of the holy wells – presented me with this book (and not just because it features a hare on its cover!) . . . This is a brilliantly written novel that concerns itself with the detailed lives of a small close-knit community – Faha – in County Clare, at the time of the heralding, and then the arrival of, electricity. The ‘voice’ of the book is a 78 year-old man remembering growing up and coming-of-age in the 1940s and 50s, and experiencing first-hand the changes that electricity brought to the order of things in rural Ireland. In fact the author – Niall Williams – was born in 1958, towards the end of that period, and has used his writer’s skills to invoke the colour and tenor of the times and, of course, the inevitable suspicions, consternations and conservatism that were inherent in a community and lifestyle which had changed very little over generations and many decades.

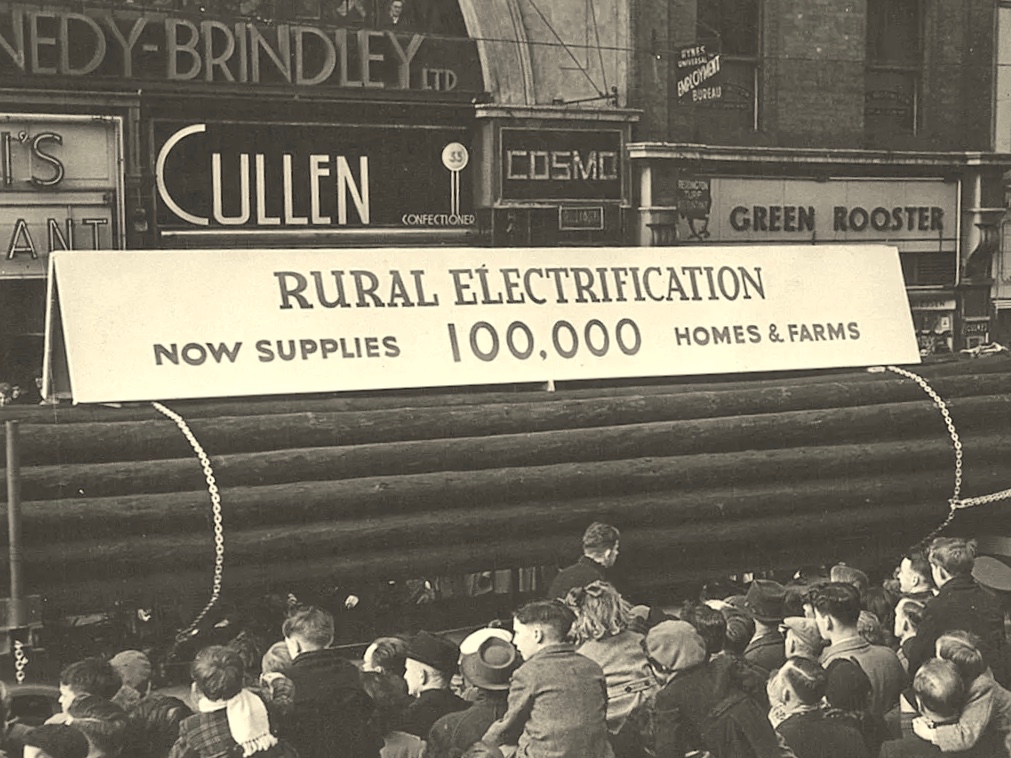

Rosses Point Village, Co Sligo: the poles arrive, 1940 (ESB Archives, which has been an invaluable source in my own search for information on the events of the time)

The book – This is Happiness – is outstanding. I consumed it eagerly, and I’m giving you a few extracts to whet your appetites. I thoroughly recommend that you read it, even if you think your interest in Ireland’s rural electrification is but brief. It’s also a story about people’s personal lives, of course, and all the characters are beautifully painted and completely credible. In terms of reality, my feelings are that Niall Williams has been scrupulous in his research, and deserves the accolade of having creatively told an absolutely true piece of social history through his particular medium of narrative romance.

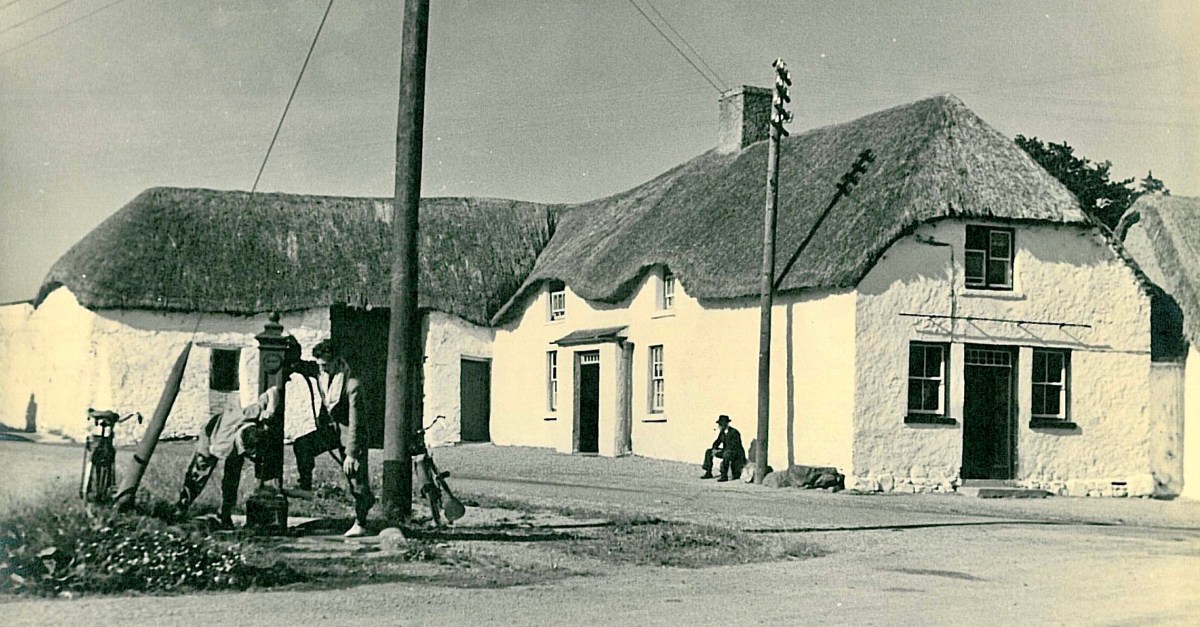

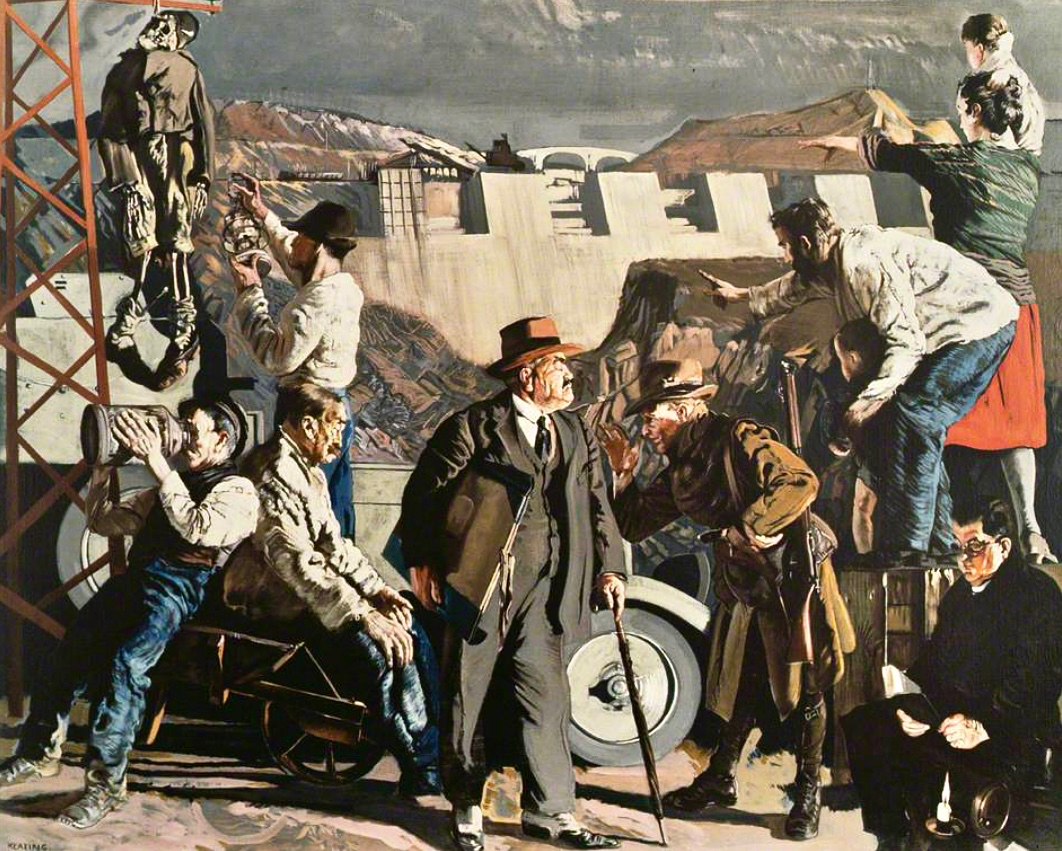

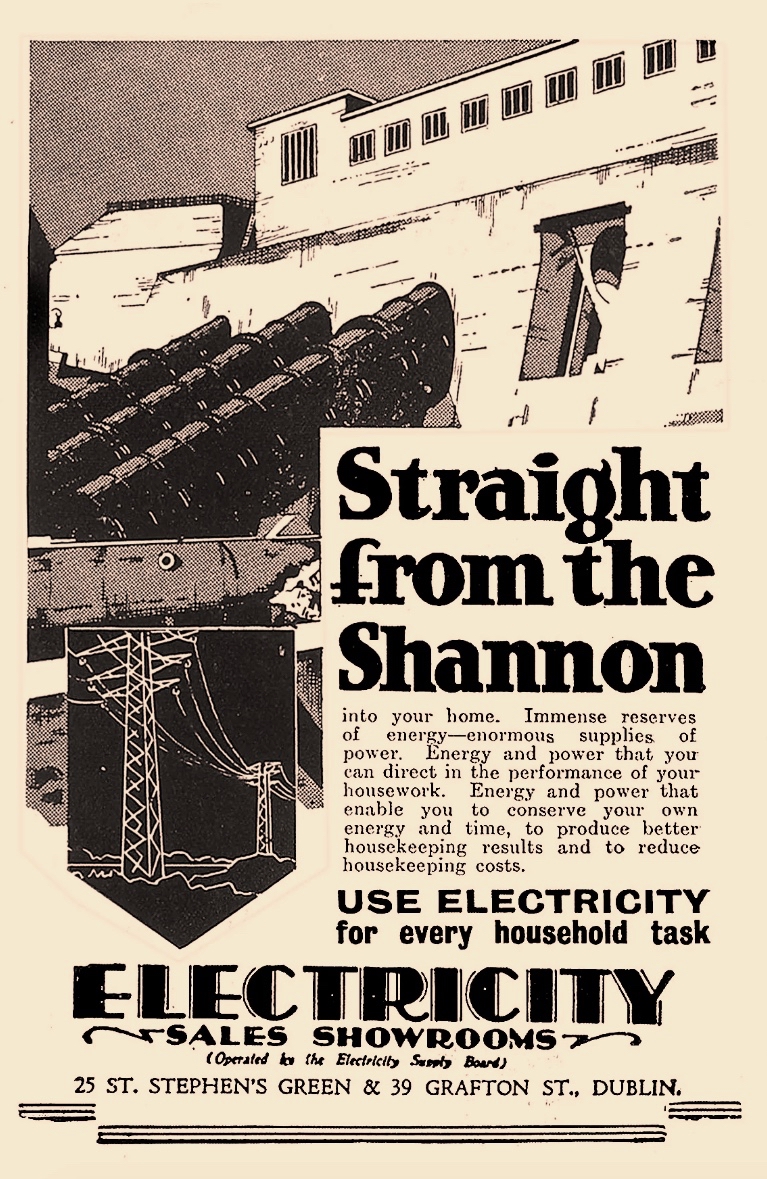

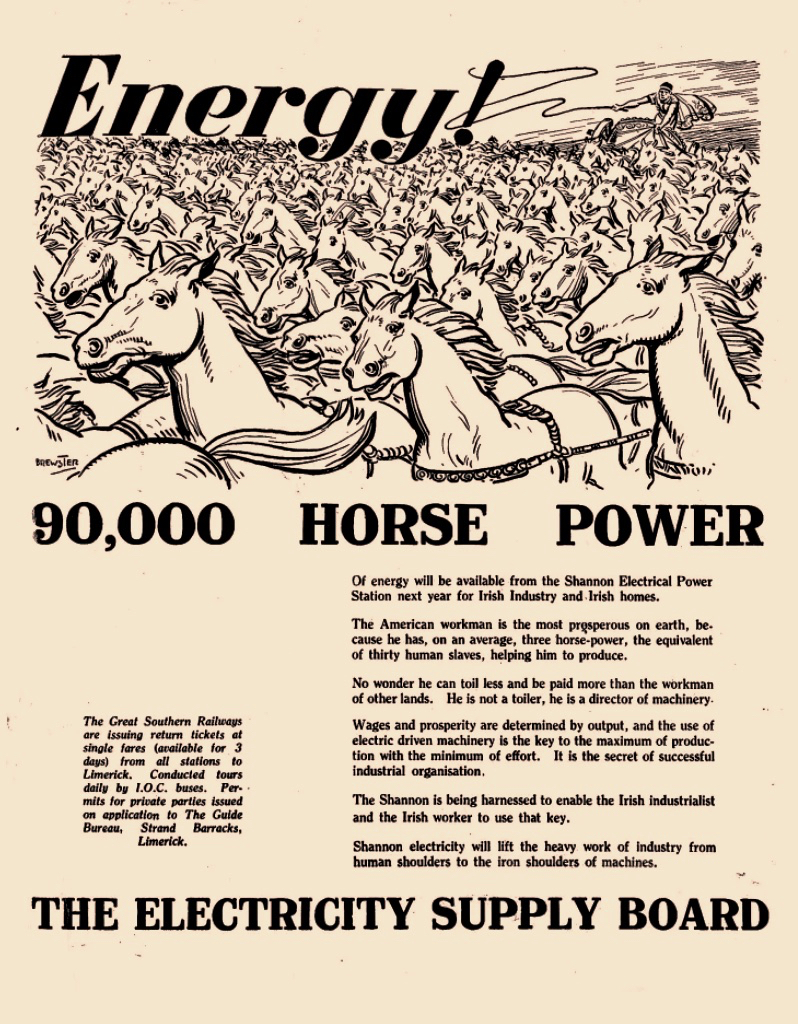

Before and After ESB Archives

Firstly, consider how ‘The Electricity’ had to be taken across rural Ireland: a landscape that was seldom accommodating – using poles and wires. Here is Niall Williams’ account of how the poles were purchased – all this can be verified:

. . . The electricity poles, it turned out, would not be Irish. Irish forests, we had learned in school, were felled to make Lord Nelson’s fleet and were now fathoms deep with the rest of the Admiralty. Instead, after extensive research, which in those days meant sending a man, the Board learned that the best place to purchase the poles was the country of Finland. To Finland they dispatched a forester, Dermot Mangan. Mangan had never been north of Dundalk. He tramped through the snow directly to the Helsinki offices of Mr Onni Salovarra, stood melting alarmingly beside the ferocious stove and said he was there to negotiate for poles on behalf of the Irish State.

Mr Salovarra thought him a novelty. He considered the comedy of the clothes the Irish thought adequate to the Finnish winter. The shoes, the shoes were little more than cardboard, a detail that inexplicably moved him, conjuring a country poor and valiantly endeavouring to overcome its circumstances. Still, business was business. Like all who had to outwit savage climate, Mr Salovarra eschewed sentiment and offered an inflated price of £4 a pole.

Mangan furrowed his brows and melted some more. He was not a businessman, his prime negotiation was with saws, but he had been told to drive for £3 and 10 shillings per pole, and if things did not progress, the Department Secretary had told him, drop in a mention of Norway, they won’t like that.

Mangan sat down. He said he was sorry he had travelled so far in vain. He said he had been hoping to see the glory of the Finnish forests, which he believed the finest in the world, but now he would have to travel on to Norway.

Mr Salovarra said £3 and 10 shillings per pole.

Mangan said he would send word back to the Government and asked for the nearest telegram office.

Right here is the only one, said Mr Salovarra and smiled. He had the kind of teeth that suggested the tearing of fish-flesh.

Mangan wrote up the words of the telegram. Please send this, he said, and passed the wording across the desk to Mr Salovarra. The message was written in Irish.

Mangan crossed the frozen street and into the tropic of a wooden hotel where three stoves were kept going and the floor of the lobby wore a permanent stain of male thaw. His room was spartan but it was overhead Reception and the heat fairly cooked him. The floorboards up there been shrinking and creaked like the bones of old men, but they dried his shoes in jig-time. In the same jig-time the stitching of them gave up the ghost and you could hear the tiny snaps of the cobbler’s thread as the soles came loose. The fish he ate for dinner was larger than the plate. He had no idea what kind it was, but with enough salt you could eat timber was Mangan’s thought.

He went back to Mr Salovarra the next day and received the telegram of the Government’s response, which was also written in Irish. Translated, it read: Delighted with offer. Accept on behalf of State.

Mangan looked across at Mr Salovarra whose teeth were smiling. ‘Offer refused,’ he said.

Mr Salovarra could not believe it.

‘Look here,’ said Mangan, and read aloud the impenetrably harsh sounds of the Irish. He finished with a flourish the sign-off, An tUasal O Dála.

Mr Salovarra asked him what An tUasal meant and Mangan explained that in Irish we remembered we were noblemen and greeted ourselves as such.

Mr Salovarra said £3 a pole.In all, ten telegrams went back and forth from Helsinki to Dublin, all of them in Irish, and, because in Irish and incapable of being translated in Finland, they were able to take on whatever degree of intransigence Mangan thought apt. Ultimately, because of the unnegotiable severity of the Gaelic, Mr Salovarra was bargained down to £2 a pole, and on that the two men shook.

But that was not the end of it. Now fearful that their inexperience might be taken advantage of, the Electricity Board insisted that each individual pole be inspected, calipered and approved by Mangan himself before being shipped to Ireland.

Mangan told Mr Salovarra he would have to stay in Finland for some months. He was to visit the northern forests in person.

Mr Salovarra lifted onto his desk the gift of a pair of fleece-lined lace-up boots and made a small respectful bow. An tUasal, he said.

Dermot Mangan travelled by sleigh to the snowbound forests of Finland. In the deep woods was a preternatural silence and the sense of the beginnings of time, and Mangan was not surprised to learn of the Finnish epic poetry of the Kalevala in which the earth is created from pieces of duck egg, and the first man, whose name is not Adam but Väinämöinen, starts by bringing trees to barren ground.

Mangan took to the woods. They were his dream habitat. He wore furs, Mr Salovarra’s boots, and went from pole to pole and made his mark, selecting the ones that in time would criss-cross the green spaces of Ireland. He became a story, and that story was well known by the electric crews that came in to Faha and told and retold it with greater or lesser detail. But the fact is that for the next 30 years, May to December, there was always a ship bringing poles from Finland to port depots in Dublin, Cork or Limerick. In the interest of story, sometimes you could do no worse than go out into the country, find one of those quiet roads where time is dissolved by rain, look out across ghost fields that were once farmed, and you’ll see still see some of those poles An tUasal Mangan first laid a frozen hand on in the forests of Finland . . .

Niall Williams – This is Happiness

One of the largest consignments of poles from Finland: the MV Make navigates the Shannon Estuary c1950 ESB Archives

One million poles were erected in Ireland, and 50,000 miles of electric cable were strung from them. Here’s the account from the book of one pole’s progress:

When we came into Quirke’s there was a quorum in shirtsleeves gathered around a fresh hole in the front field there. Quirke’s was mostly stones and the pole was on the ground while the men assessed whether enough stones had come out to make a third attempt to stand it. When Christy and I came into the avenue our arrival seemed propitious and we did the thing all men do, we came over for a look into the hole, nodding the tight-lipped nods that masqueraded as expertise. Two long lines of rope ran across the grass to a jittery grey horse waiting with Quirke. The third attempt was decided by a smack of the ganger’s hands. Christy threw off his jacket and, because there are coded imperatives in the company of men, I did the same, we stood in to raise the pole.

With a sharp hup hup from Quirke and a worry from his rod of osier the horse took the tension. Head down and hands out on the sticky sweat-melt of the creosote, I saw nothing and heard only the grunts of effort and the come on come on of the ganger, the now now, men as the shaft of timber sank into the hole and then began to rise like a giant’s needle into the sun. It was wonderful. I felt a surge of joy, the simple, original and absolute thrill of a physical victory over the ardours of the terrain, a pulse so quick as to pass instantly in through the arms of each man, into the blood and brain the same moment with the pole triangled now at nine o’clock, now ten, Come on come on, effort increasing beyond the point when no increase seemed possible and yet was found.

And because of that surge, because I was given over completely to the thrust of a communal triumph I had never experienced before, I didn’t hear the rope snap…

Niall Williams – This is Happiness

From the earliest days – 1946 ESB Archives

Niall Williams vividly recreates a gathering in Faha when the people of the village were summoned to a demonstration of what the benefits of ‘The Electricity’ might herald:

. . . One afternoon the stools and chairs were brought in from the garden and set around the kitchen because a summit of the neighbours had been called. Moylan, a salesman from the electricity company, was doing the rounds. Because it had the telephone and the air of unofficial post office, because it was already deemed connected, my grandparents’ house was chosen for the demonstration of what the future was bringing.

The meeting had been called for three in the afternoon. Moylan was a nine-to-five man, three was when he was at his peak, and country people have no work that couldn’t be left aside for something as essential as electricity, was his position. A Limerick baritone with a magnificent sweep of black hair, he arrived in the yard in the van. Sonny, help me carry these in, was his greeting. When he saw the smallness of the kitchen – the slope of the floor doubling the cramped illusion – he had to overcome the familiar fall of his heart that this was a lesser stage for his talents, and not let it impact upon his performance.

‘Where is everybody?’ He asked Doady.

‘Everybody is coming,’ she said.

Into the kitchen on a handcart Moylan hefted a selection of machines whose existence to that point had been notional. Many were white and of such a gleaming newness it seemed nothing in the parish was as white as had previously been thought. All had a black wire coming out the back with a three-pin plug that looked both imperative and nakedly masculine, as though in urgent need of finding a three-holed female. Moylan laboured to get the washing machine in and around the turning of the front door whose jamb was predicated on human dimensions. Doady said it was a shame Ganga wasn’t there to help. The turf needed turning, he’d announced abruptly that morning, and headed with Joe (the dog) to the bog.

In clusters of shyness, the neighbours began arriving.

Moylan had already given a performance in the village, and the reviews were good. ‘Nice little house you have,’ he said to Doady, the sweat shining off him standing in front of the twelve-foot hearth where small sods were sighing a complacent smoke unaware that their time was running out.

The centre of the room was taken with the machines and the neighbours came in around them muted and respectful the way they did when there was a body laid out. They settled into the chairs, onto the stools and benches, and let their eyes do the talking for a while. Mostly it was the women. Those who were not eyeing the electrical equipment were taken by Moylan’s shoes, which were two-toned, extra-terrestrial, and with an air of Hucklebuck. Maybe the Shimmy Shake too.

While the practical business of bringing the electricity to the parish was almost exclusively the domain of men, inside the houses the jurisdiction over electrical equipment, kettles, cookers, hairdryers and washing machines, was conceded to women. Only two men came to the summit. First, because it was taking place in the kitchen in daytime, and second, because men refused to be summoned, it outraged their dignity, and nothing in the known world had yet required that absolute submission accept Christ, and even with Him it was leeway. The two men were Bat from back the road who came in, God bless all, with cap low and eyes down, and Mossie O Keefe who was the Job of Faha . . . O Keefe’s mother died when the cart turned over on her, his father went into the bottle, he himself married the woman in love with his brother, one of his sons went in a threshing machine, the other drowned in a ditch.

There were others, the room filled and the sunlight blocked at the window, but Moylan couldn’t wait forever. Emboldened by the air of event, and with the fattened authority of farmyard matrons, three hens came inside the open front door, nestling down in a bath of sunshine to watch. Neither in nor out, I was perched on the back step.

To give Moylan his due, he had his routine down pat, Now I want you first to look at this, a combination of science and circus in an actor’s boom, This, this machine, will do all the work. It will wash your clothes for you. He lifted the lid and drew out a white towel, as though the washing and drying had happened in the time it took him to say the sentence and here was the proof. He had devised this touch himself and was proud of it. It was the only proof possible without electricity and had the added boon of making it seem as if he himself was the current or at least its conductor. Further to this, ten seconds into his pitch a film of sweat was glistening on him, lending him a shine which he didn’t dab away, believing it translated as electric excitement and disguised the actual truth, that he was being cooked by the fire.

His audience was rapt by the important and foreign sounds of spec and kilowatt in that 200-year-old house, and by touch and look Moylan kept relaying the words to the magic of the machines that sat mute but powerful like idols . . .

Niall Williams – This is Happiness

An early shop selling electric appliances – Blackwater, Co Waterford, 1955 ESB Archives

I have set out these extracts from what is a good-sized novel. Hopefully they will whet your appetite and make you seek out the book: it’s a good read. Finally, I’m taking a page which is close to the end of the story. And this isn’t just about electricity – it’s speaking of a vanished part of Ireland’s rural history:

. . . My grandparents never took the electricity. They didn’t act as though there was a lack. They carried on as they were, which is the prayer of most people. They lived in that house until they were carried out of it, one after the other. Because the twelve sons in the corners of the world couldn’t reach a verdict, the house was left to itself. The thatch started sagging in two places like consternated eyebrows, brambles overtook the potato ridges and came up the garden, and soon enough in under the front door. Soon, you couldn’t see the house from the road. Soon, too, the bits of hedging Doady had stuck into the ditch to camouflage the broken Milk of Magnesia bottles grew to twelve feet and fell over and grew along the ground then, marrying thorn bushes and nettles and making of the whole a miry jungle. When the roof fell in the crows that were in the chimney came down to see the songbirds sitting in Ganga’s chair eating Old Moore’s and that way becoming eternal. When grown a man, one of the Kellys took out the kitchen flagstones for a cabin he was making. He took out the stone lintel over the fireplace after, and a year later came back for half the gable when he needed good building stones for a wall.

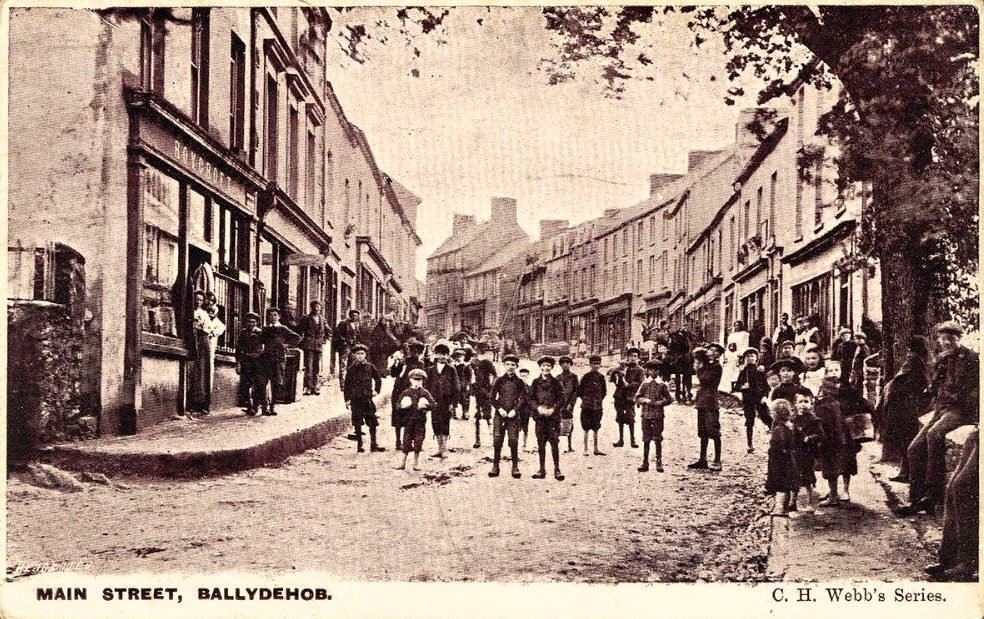

In time, as with all modest places of few votes, Government would be looking the other way when its policies closed Faha’s post office, barracks, primary school, surgery, chemist, and lastly the pubs.

In time, the windmills would be coming. Gairdíen na scoile and Páirc na mónaigh would be bulldozed to straighten the bends in the road to let the turbines pass. Any trees in the way would be taken down. Two- and three-hundred-year-old stone walls would be pushed aside, the councillors, who had never been there, adjudging them in the way of the future.

By that time, my grandparents’ house would be another of those tumbledown triangles of mossy masonry you see everywhere in the western countryside, the life that was in them once all but escaping imagination . . .

Niall Williams – This is Happiness

Switching-on ceremony Kilsaran, Co Louth 29 January 1952 – the 55,000th consumer! ESB Archives

A big thank you to Amanda Clarke for sending this book my way!

This is Happiness by Niall Williams, published by Bloomsbury 2019