Gorta, by Lilian Lucy Davidson, courtesy Ireland Great Hunger Museum

The potato crop failed first in 1845. Patrick Hickey in Famine in West Cork relates the discussion at the annual Skibbereen Agricultural Show dinner in October. Much congratulatory talk about the progress that had been made in agriculture, was brought to an abrupt end when the inevitable topic of the potato disease raised its ugly head. While several landlords and farmers felt the crisis would pass quickly, and others placed their faith in the new dry pits championed by the Rev Traill of Schull, Dr Daniel Donovan brought them down to earth with a first-hand account of the calamitous conditions all around them. Fr Hickey puts it poetically when he says, As these gentlemen headed home that night the sound of their horses’ hooves on the stony road rang the death knell of pre-famine Ireland.

Planting Potatoes – each cottage relied on an acre or so to plant enough for a year

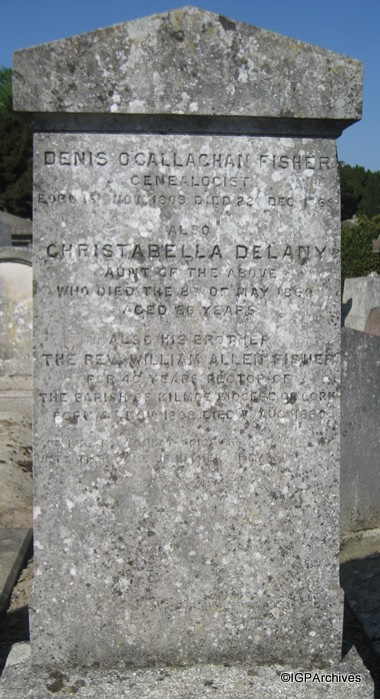

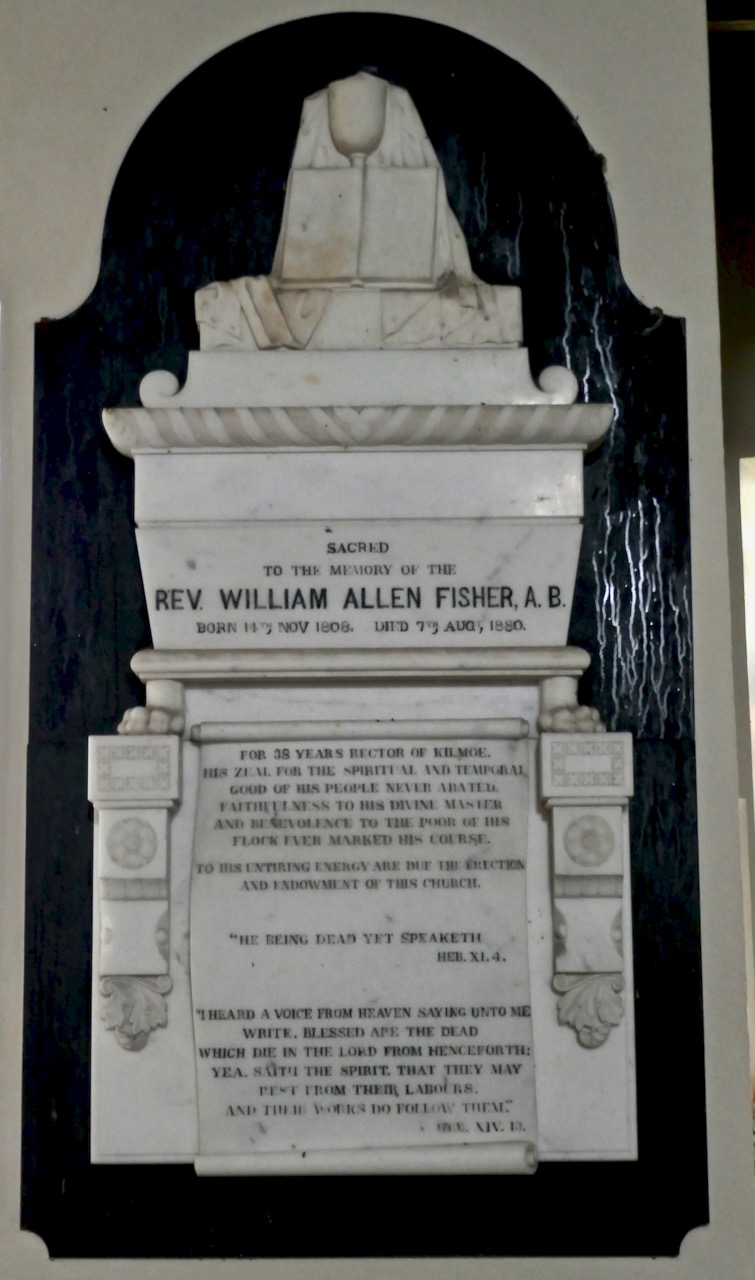

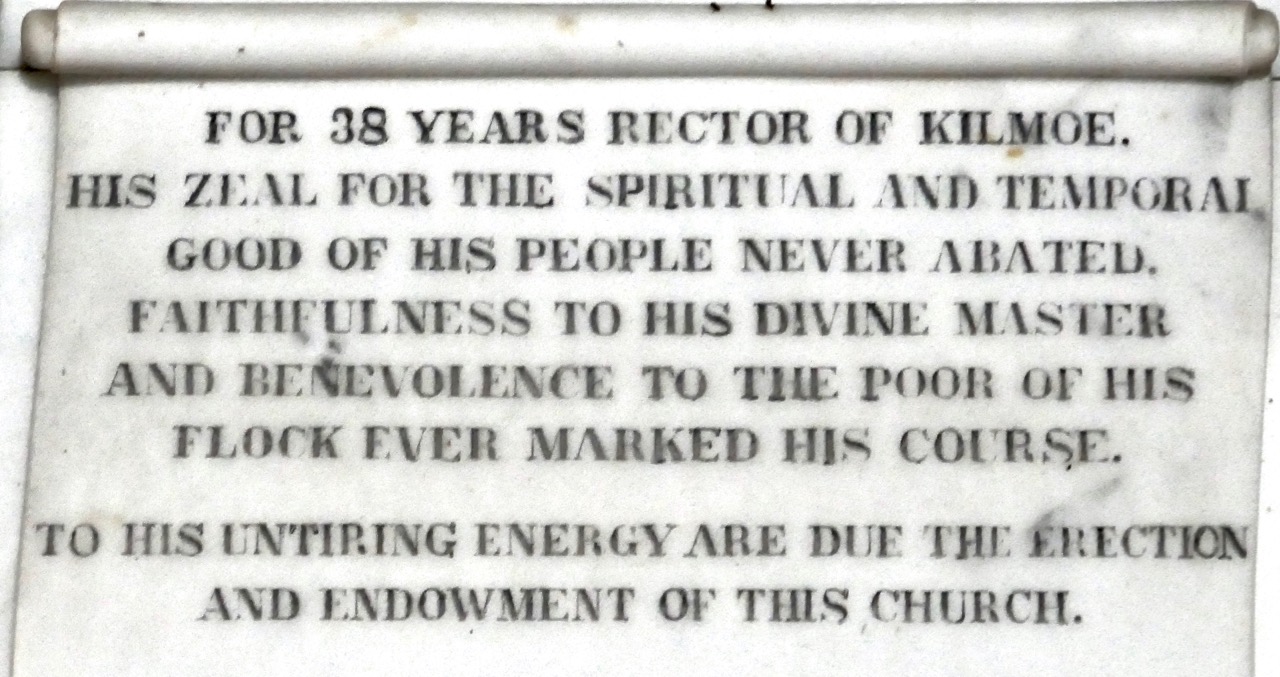

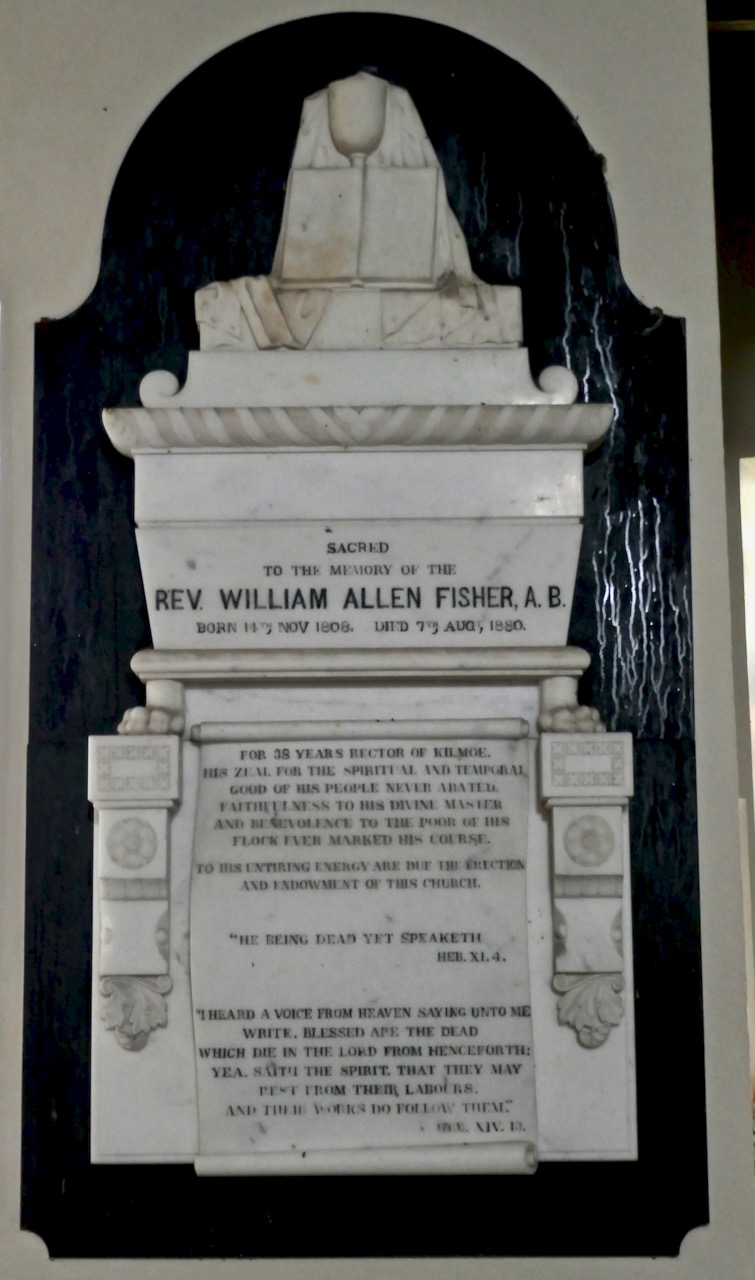

Relief Committees were struck and established food depots. In the Parish of Kilmoe the Rev Fisher and the Parish Priest, Fr Laurence O’Sullivan each contributed £5 as did other members of the committee. The ethos of the time was very much to tie relief with work and soon various schemes were proposed to the Board of Works and although one was initially approved no funding ever materialised. Distress was widespread.

The ‘lazy bed,’ in fact a labour-intensive cultivation method, has left its mark on the landscape all over Ireland

But it was the second failure of the potato crop in 1846 that precipitated a full blown famine environment. The workhouses started to fill, hungry people pawned anything they had and reports of death by starvation and fever started to pour in. The Parish of Kilmoe, which stretched from Schull to Crookhaven, encompassing Toormore and Goleen, was particularly hard hit. The Board of Works, inexplicably declined to fund any road or pier-building schemes. According to Hickey, The only refuge these hungry people had was the Kilmoe Relief Committee but even this was now in dire straits.

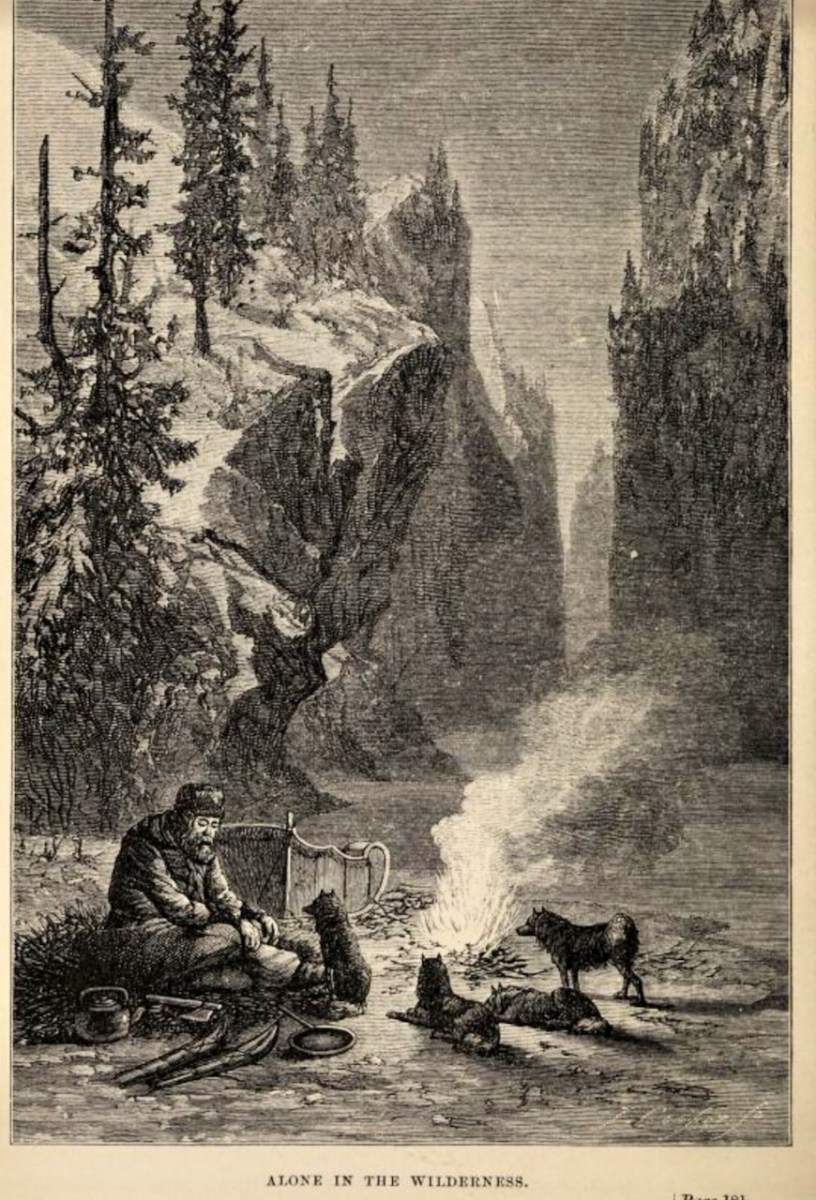

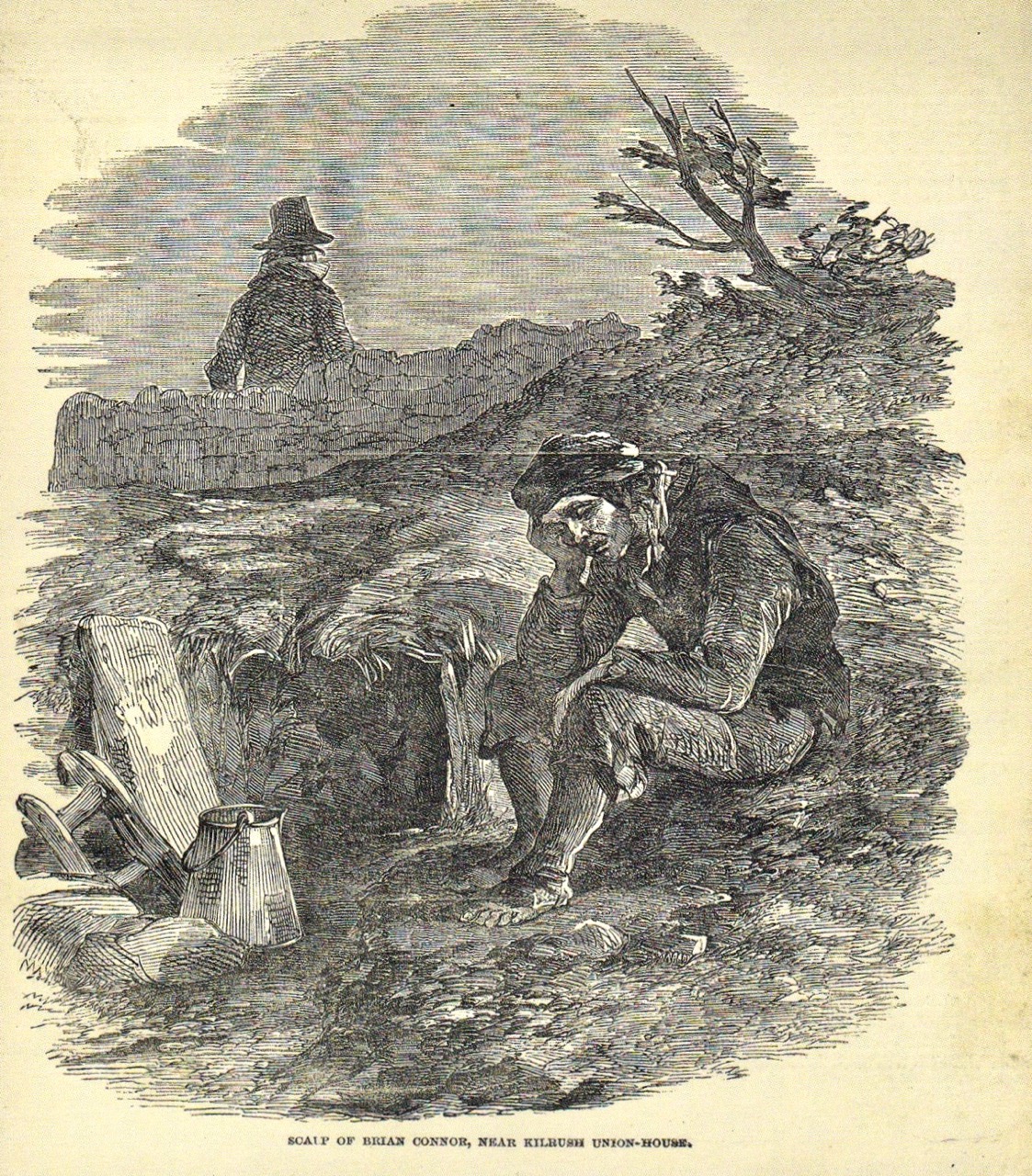

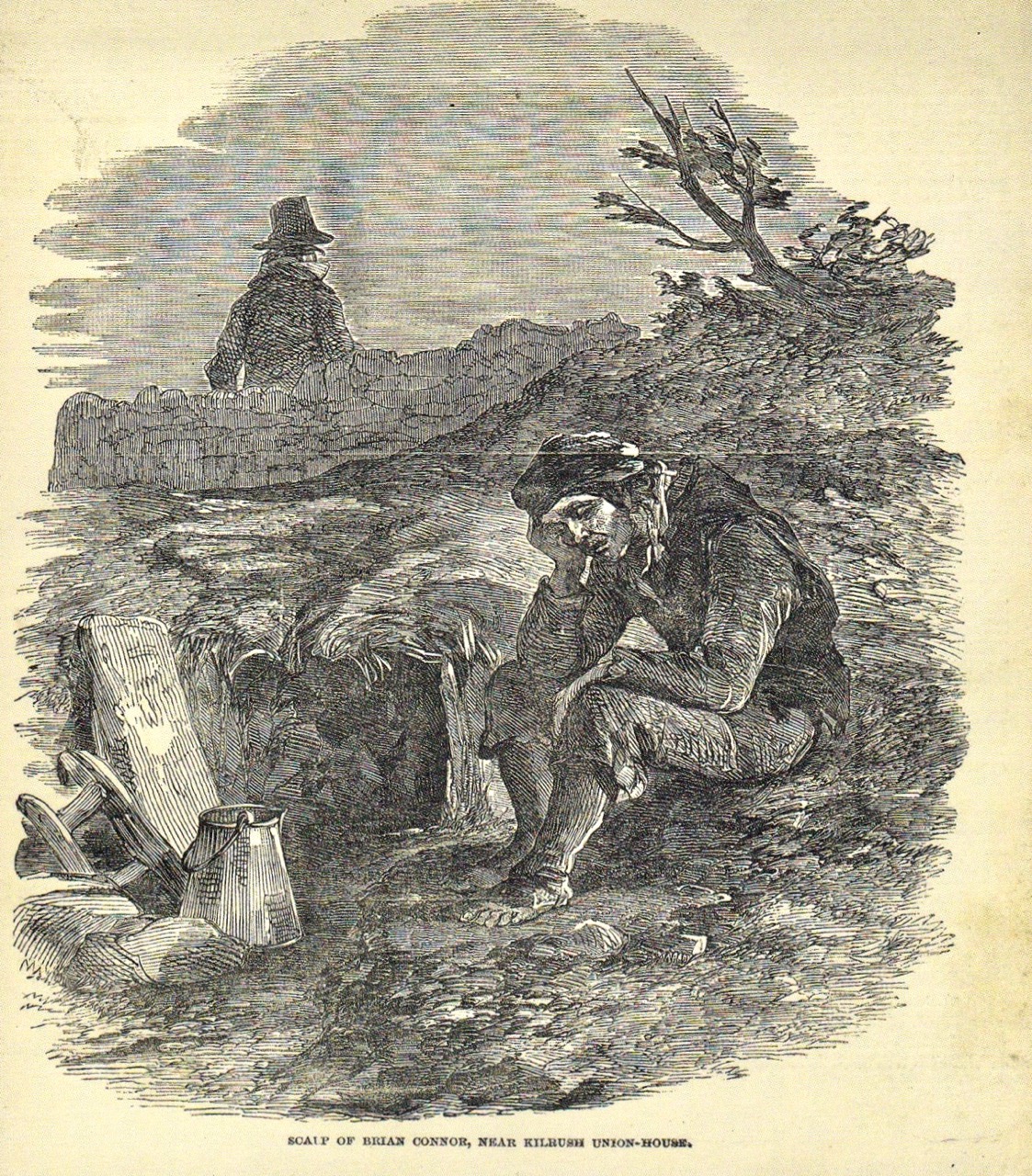

A ‘scalp’ was a just a hole dug in the earth. People resorted to living in such troughs when they had been evicted

How dire? I will let the committee speak for themselves – here are the proceedings of their meeting on November 3rd, 1846, sent to newspapers in the hope that it would elicit compassion and aid. It has all the impact of immediacy and desperation in the face of appalling official indifference, made all the more powerful by being sent by normally polite and government-supporting educated men.

Proposed by the Rev W A Fisher, Rector, and seconded by the Rev Laurence O’Sullivan, PP;

1. That this committee having repeatedly tried, but in vain, to arouse the attention of the government to the state of destitution and distress in this remote district, have determined to bring the matter before the public, through the medium of the press.

Proposed by Richard B Hungerford, Esq, JP and seconded by the Rev Henry P Proctor;

2. That the following statement of facts be forwarded: — “The parish of Kilmoe contains 7234 inhabitants, or 1289 families; we calculate that 7000 inhabitants require food, in consequence of the failure of the potato crop; the parish produces very little corn. Potatoes feed the people, the pigs, the poultry, the cows, the horses; and enabled the fisherman to dispose of his fish, for which he did not this year get as much as paid the expenses of taking and saving it, as the poor, from the destruction of the potato crop, are unable to purchase it. Thus deprived of their only means of support, they are now literally famishing. All this, in substance, we have stated over and over again to the Lord Lieutenant, the Lieutenant of the County, the Commissary-General, and the Commissary at Skibbereen. We asked a depôt – we offered a store free of expense – we entered security – and when we had done all this, at the end of a month we received a letter from the Castle, with a paper on brown bread enclosed, to say we had better purchase wheaten and barley meal.

Proposed by the Rev Thomas Barrett, RCC and seconded by Mr John Coghlan;

3. That this committee feel quite unable to meet the views of the government. There are only two resident gentry in this district – there are no merchants here – there are no mills within twenty-three miles – there is no bakery within that distance – nor is there any way of procuring food, except through the medium of our committee, which, out of our limited funds of 165l., have kept up a small supply of Indian meal and even with our very best exertions, in consequence of our trifling finances, and being obliged to bring our supplies from Cork by water, we have been twice, for a fortnight together, without meal.

Proposed by Mr B Townshend and seconded by Mr J Fleming;

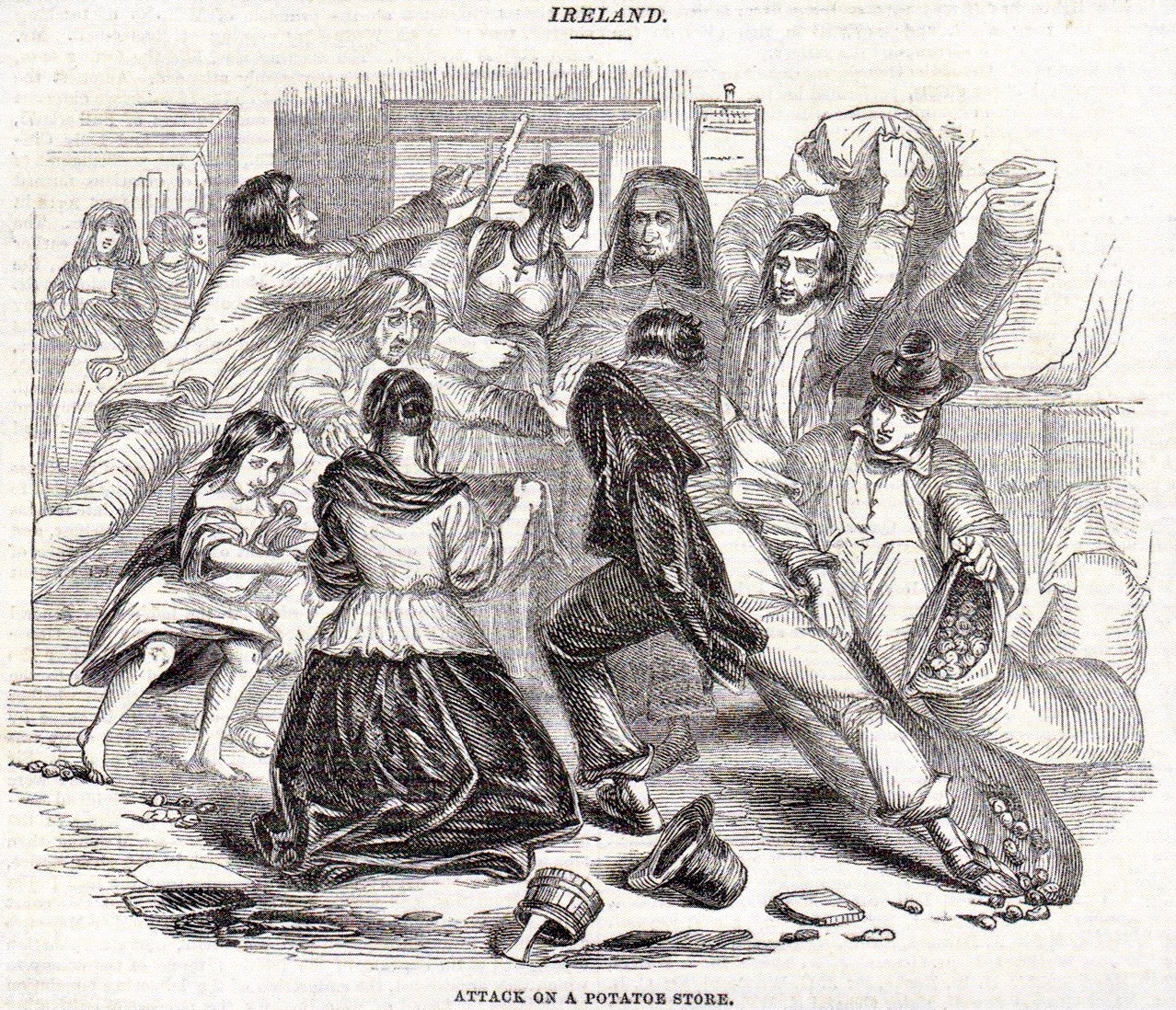

4. That our funds are now exhausted, and we have no means of renewing them, while the demand for food is fearfully increasing. We see no other way left to us but to try, to the medium of the press, to arouse the government to a sense of the fearful state of things which is inevitably impending. Rapine has already commenced and who can wonder? Many are living solely on salt herrings – many more on seaweed; and when our last supply of Indian meal was sold, they offered 3s. a stone – and would not go away without it – for some that was damaged, the very smell from which was so offensive that it was thought unfit and dangerous food for human beings.

Proposed by the Rev Laurence O’Sullivan, PP and seconded by Mr A O’Sullivan

5. That these resolutions be published in all the Cork newspapers, the Dublin Evening Post, Dublin Evening Mail, and the Times London newspaper and a copy be sent to Lord John Russell and Sir Randolph Routh, with a faint hope that something may be done without delay (for the case is urgent) to relieve our misery and want, else the public will soon hear of such tales of woe and wickedness as will harrow the feelings and depress the spirits of the most stout-hearted man.

Signed

Richard Notter, Chairman.

W A Fisher, Rector of Kilmoe, Sec

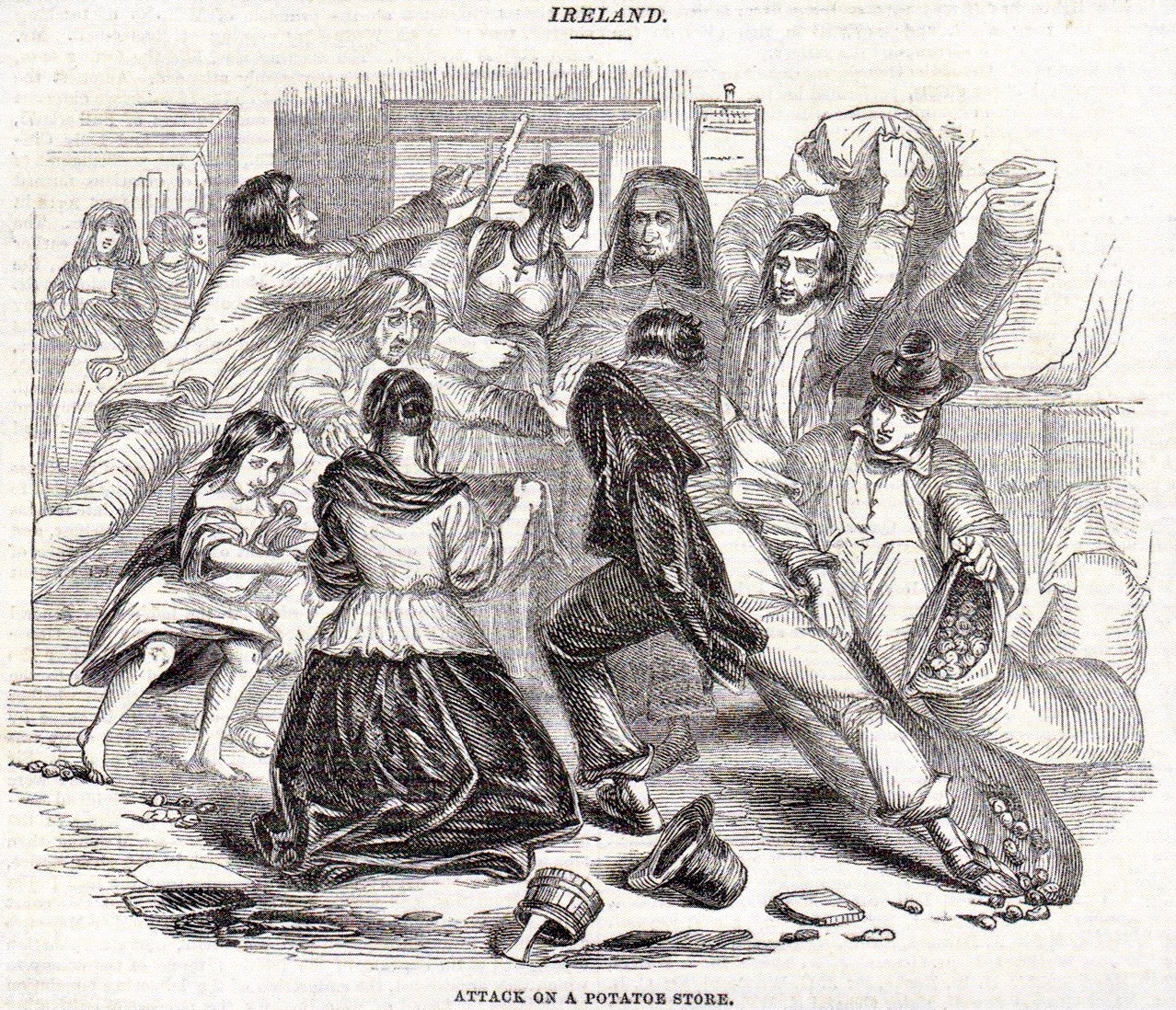

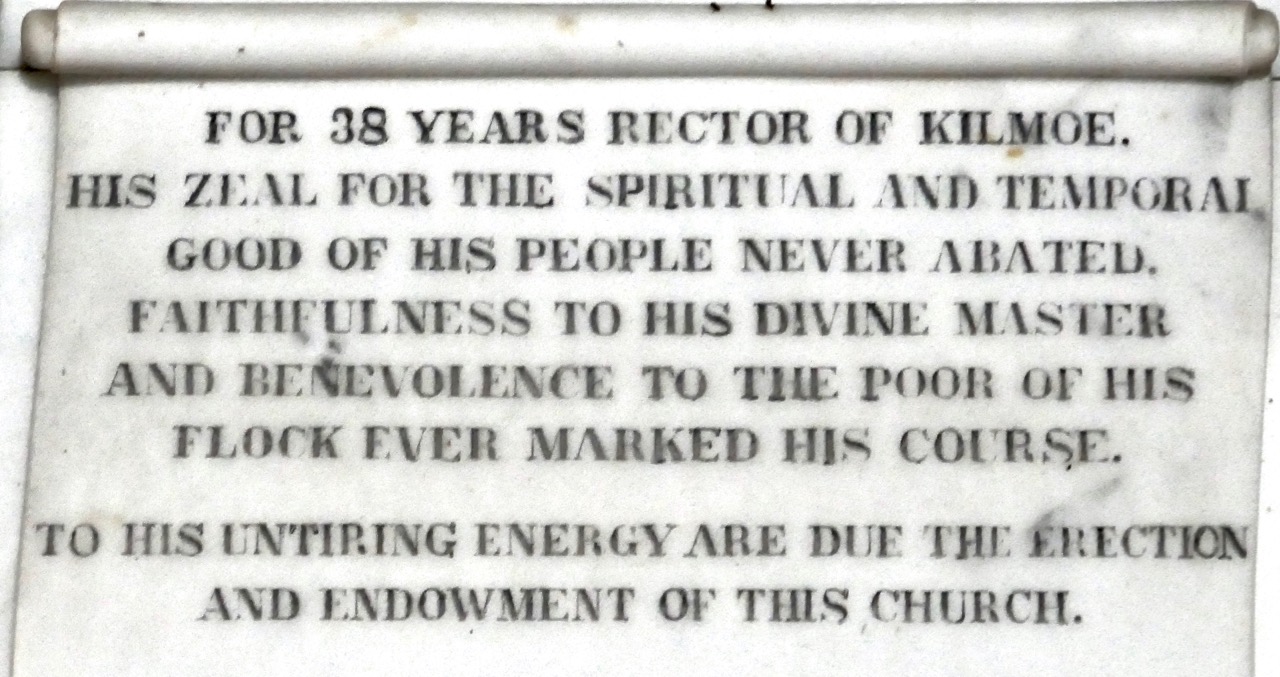

Upper: Memorial tablet to Richard Notter in the former Church of Ireland in Goleen. Lower: an example of the kind of ‘rapine’ predicted by the letter

Besides a stark description of conditions in Kilmoe, what these minutes show is that the relief committee was composed of both Catholics and Protestants, of clergy and lay men, drawn together in a common cause and working in a cooperative spirit. Perhaps as a result of this letter, a Board of Works road-building project was eventually implemented on the Mizen. These hated schemes were riven with administrative problems of all sorts, the most serious being a delay in paying the labourers.

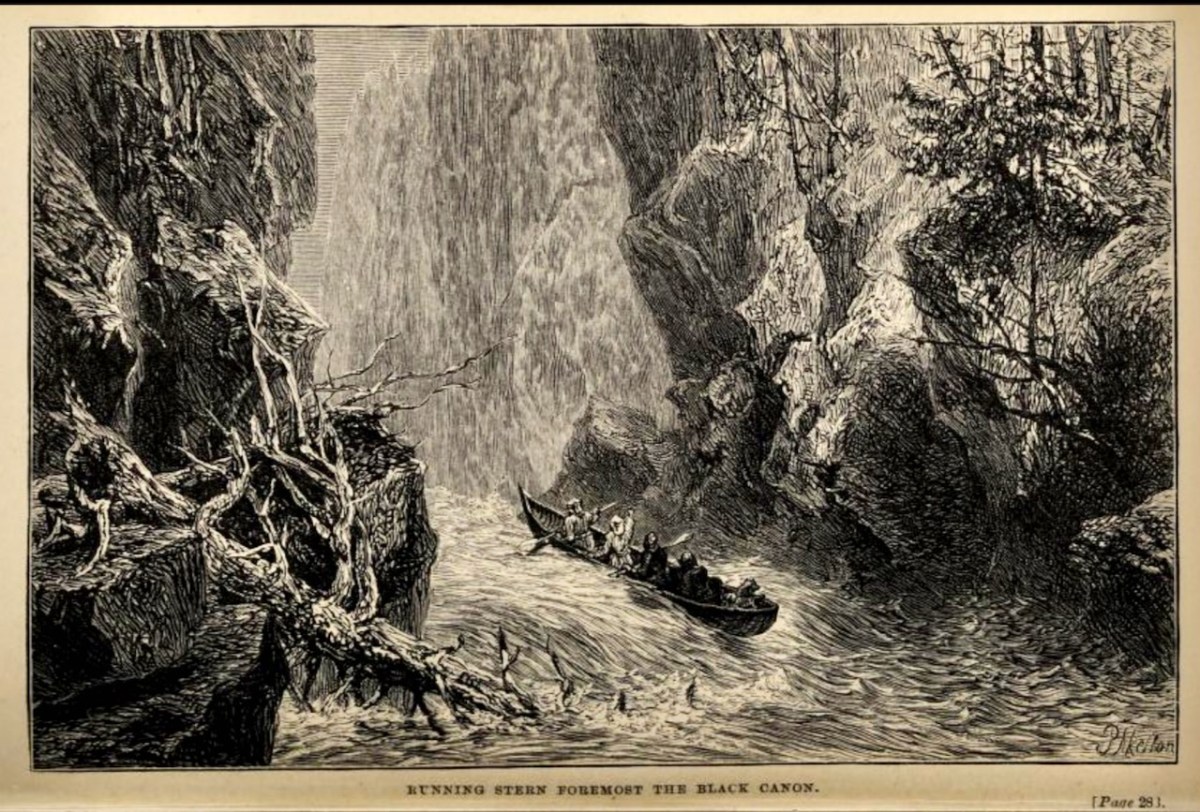

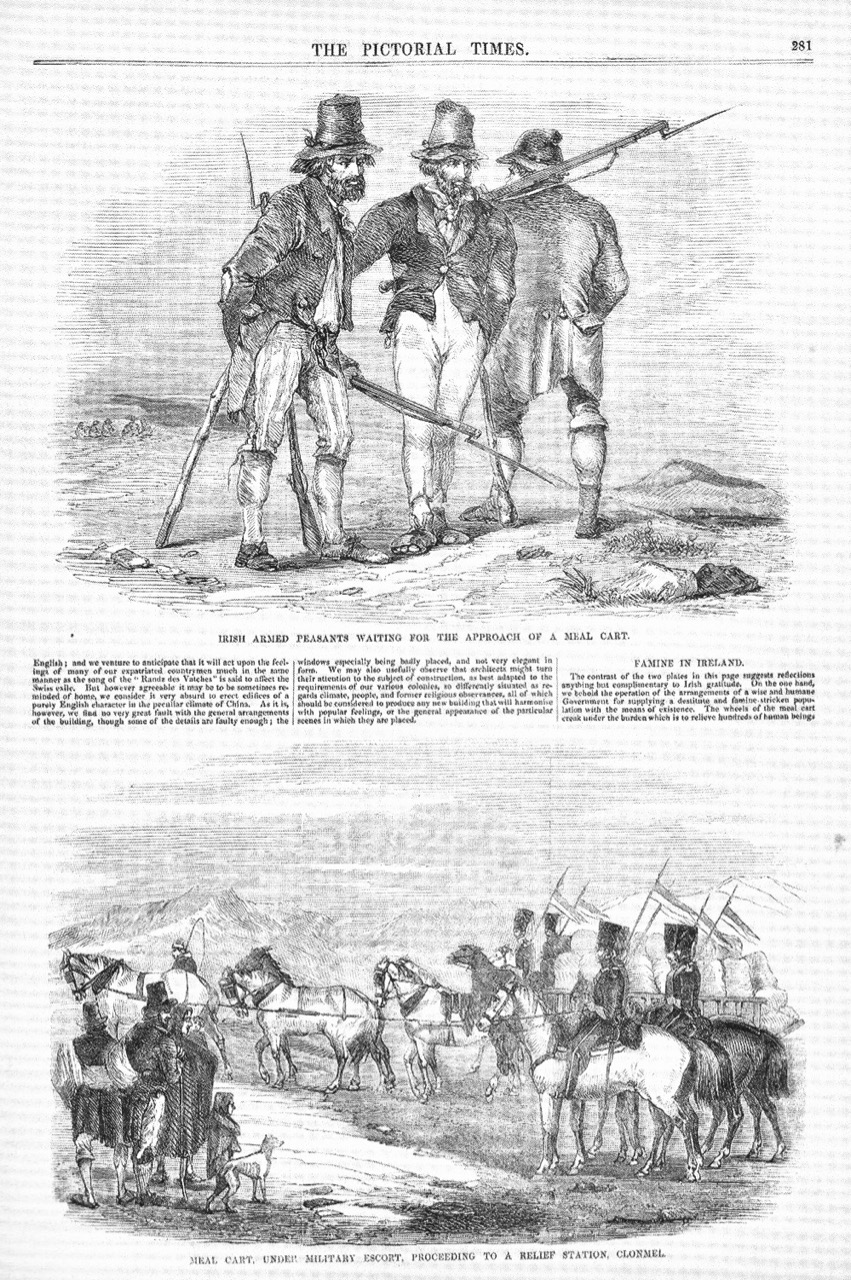

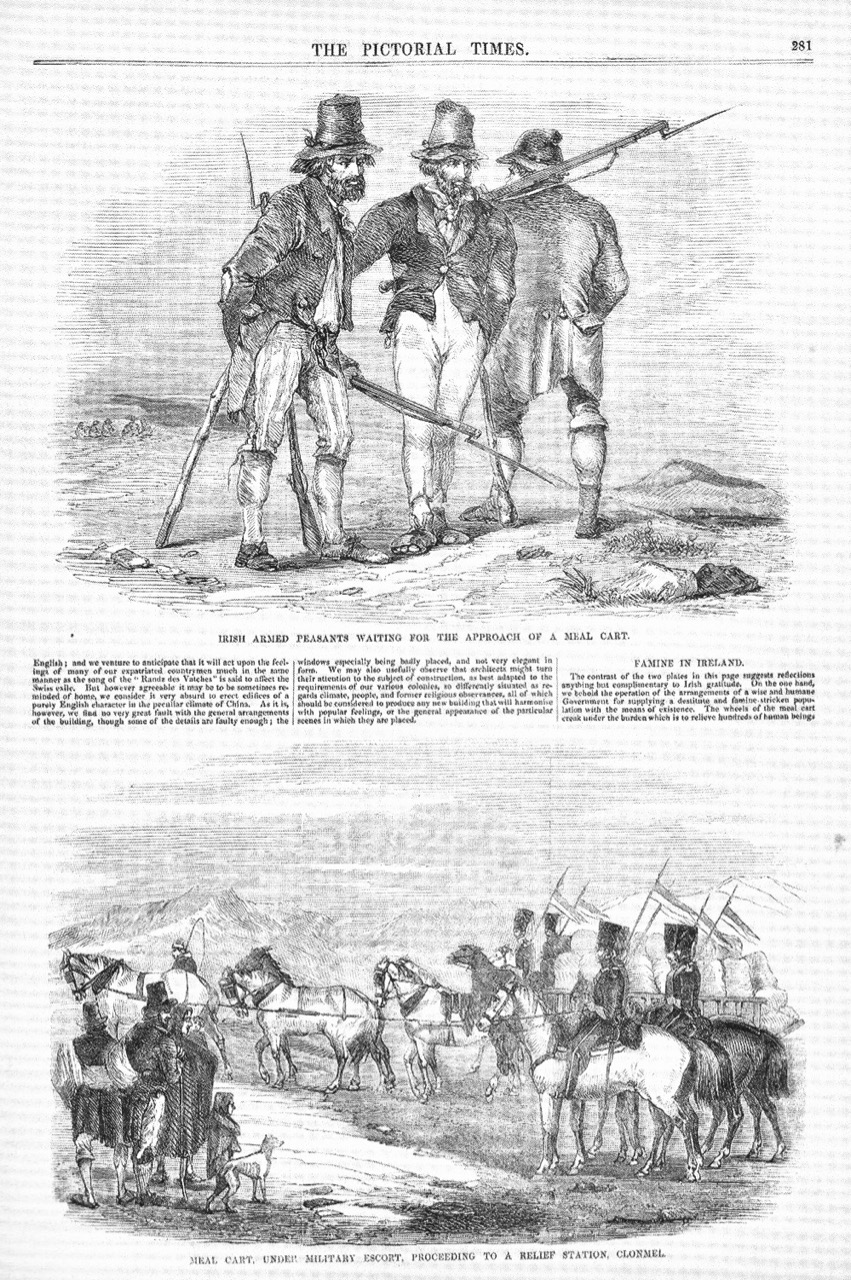

Meal being delivered under armed guard

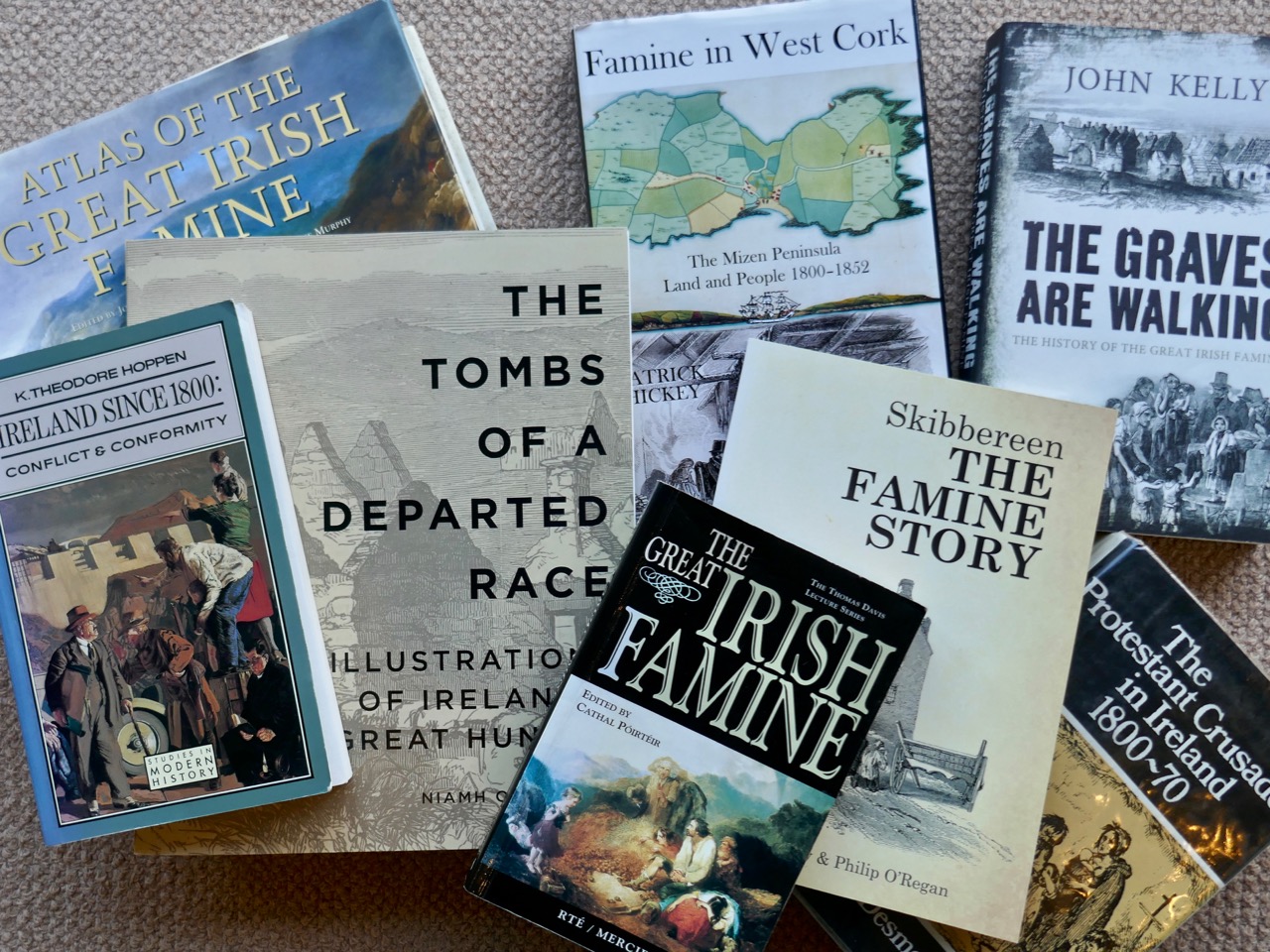

Because this is the story of Teampall na mBocht and Rev Fisher, I cannot dwell here on a detailed description of the harrowing progression in Kilmoe of the Great Hunger. Much has been written about the famine in West Cork, and I direct the reader to Patrick Hickey’s book, which has been my main resource. (In the final post I will supply a list of the resources I used for this study.) I confess that I find it difficult to write about the famine itself – it’s amazing how raw and emotional it becomes once I immerse myself in the subject. Anger wells up very quickly and I recognise a desire to find culprits to blame (there is no shortage of candidates) and to jump to judgement using a modern mindset and all the benefit of hindsight.

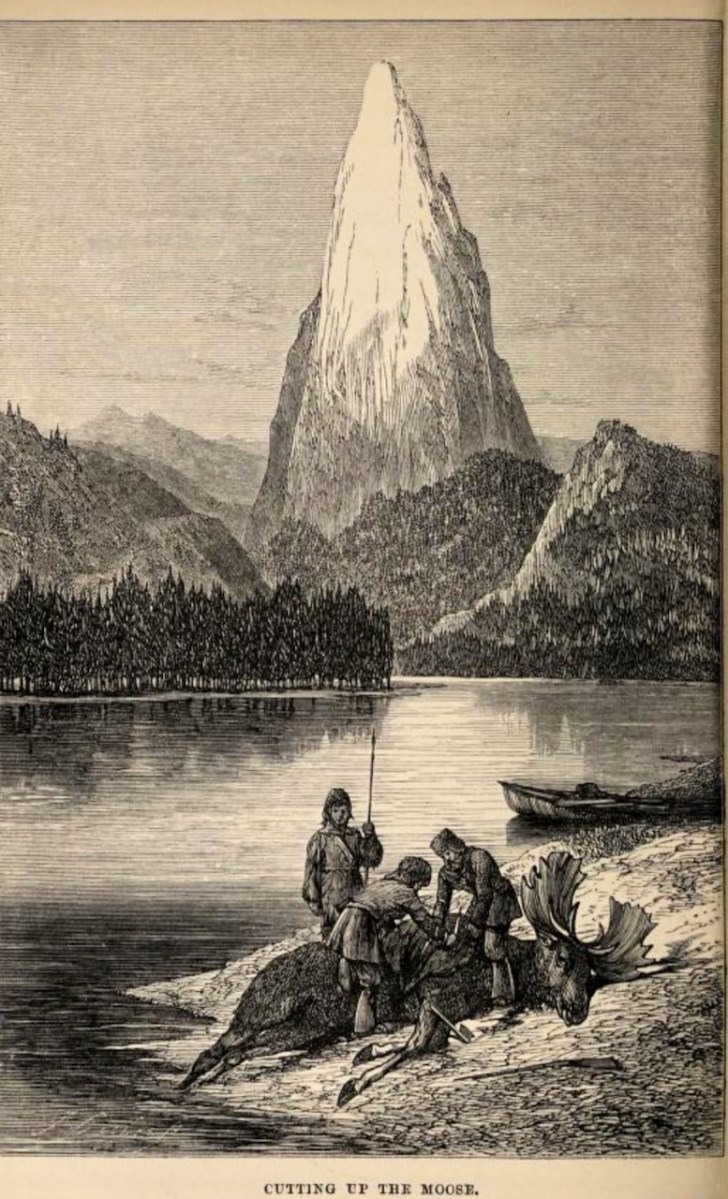

The Rev Traill, drawn by James Mahony for the Illustrated London News, in Mullins hut, while Mullins lies dying on the floor. Mahony stood “ankle deep in filth” to capture the image

For now, then, let’s get back to Kilmoe, William Fisher and Fr Laurence O’Sullivan, central actors in our drama. One digression, though, remember the Rev Robert Traill and how he railed against the wicked priests for opposing his tithes? He was very much part of the relief effort too, setting up ‘eating houses’ in cooperation with Fr Barry of Ballydehob (the regulation ‘soup kitchens’ did not provide food they considered nutritious enough) and travelling throughout his parish indefatigably providing assistance to all, Catholic and Protestant alike. When he came down with famine fever in 1847 he couldn’t fight it off, and died in April, mourned and honoured by everyone for his heroic efforts.

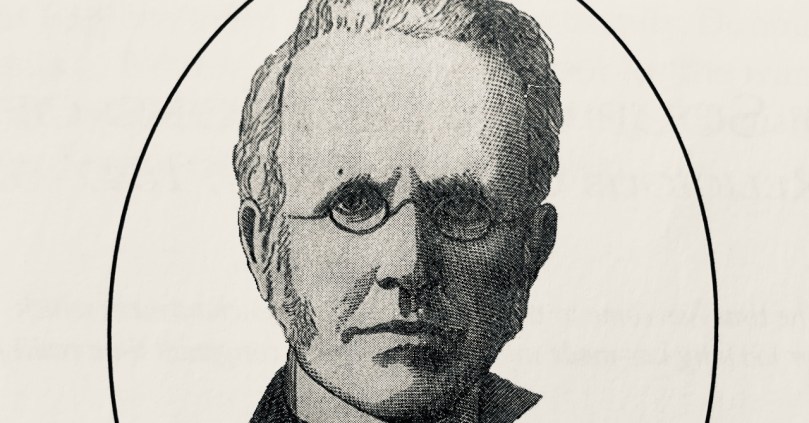

Rev Fisher had a printing press and used it to great effect, sending requests for aid to everyone he knew. Money arrived, and it enabled him to help a great deal with the relief efforts. Like the Rev Traill, he also contracted famine fever but managed to recover. It was during this period of recovery that he started hearing confessions. He was strongly influenced by the Tractarian Movement, a return to High Church liturgies that came close to Catholic practise. He claimed that he simply made himself available in his vestry and that the people poured in, wishing to unburden themselves of their sins. Soon, his church, in Goleen, was filled with the newly-converted.

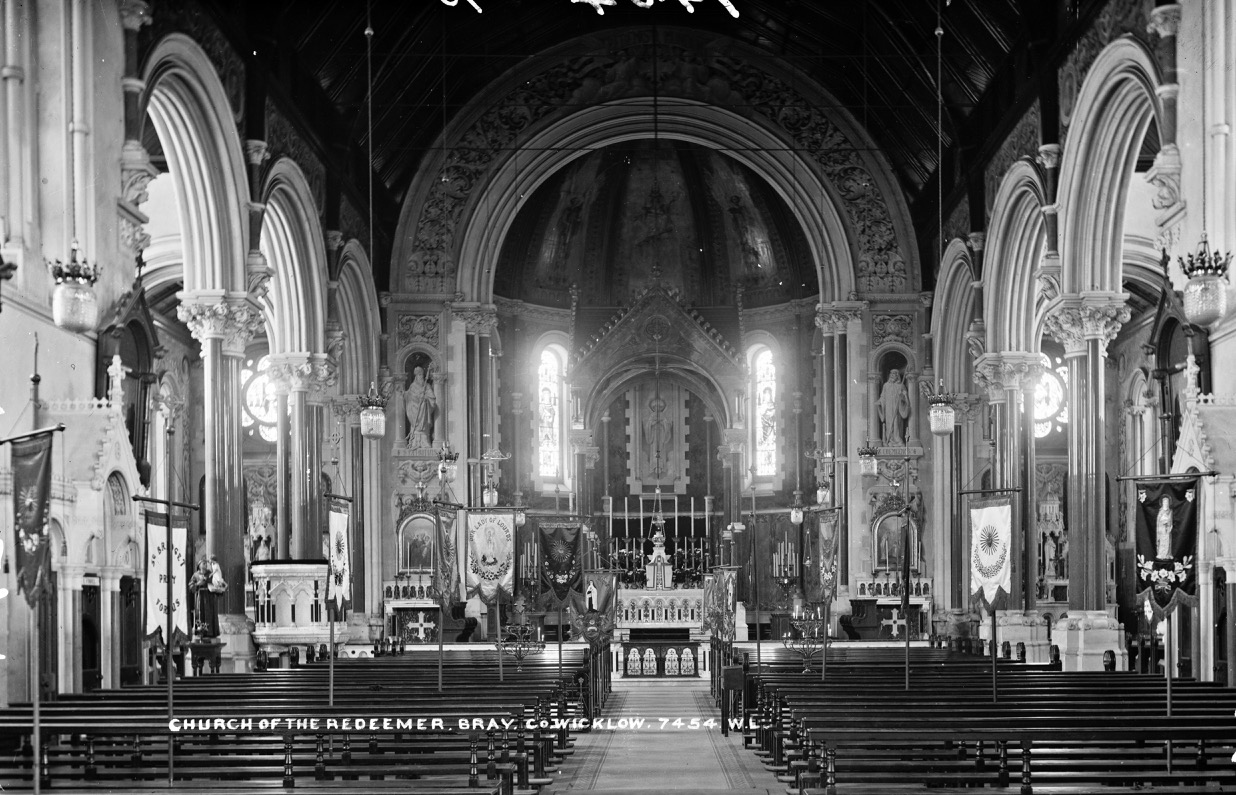

The former Church of Ireland in Goleen, now used for mending sails. Here, Fisher heard confessions and welcomed converts

In his book, The Protestant Crusade in Ireland, Desmond Bowen makes the claim that Catholics in the area were completely demoralised; they quarrelled with their priest who fled the community. However, Hickey points out that Bowen provides no source for that information, whereas Hickey tracked down Fr O’Sullivan’s movements and found that he left for only a short time (possibly ten days) to fund-raise (successfully) in Cork. Tellingly, he had withdrawn from the Kilmoe Committee as a result of dissension between the clergymen. Laurence O’Sullivan, in fact, remained in his parish throughout the famine and worked to raise and disburse funds as well as to feed his parishioners, also contracting famine fever which knocked him out of action for at least two months.

Fisher’s fund-raising efforts eventually enabled him to contemplate a building project. He considered first a school, and then a church. It would be built using only manual labour in order to ensure that the work was done by the poorest, and not farmers with horses and carts, and called Teampall na mBocht, Church of the Poor. At the same time, Fisher was donating money for food to schools (leading to a dramatic increase in enrolment) and trying to encourage a return to fishing by local fishermen. Hickey acknowledges, Whatever about the conditions of aid, implicit or explicit, Fisher organised the distribution of large supplies of food and this saved many lives.

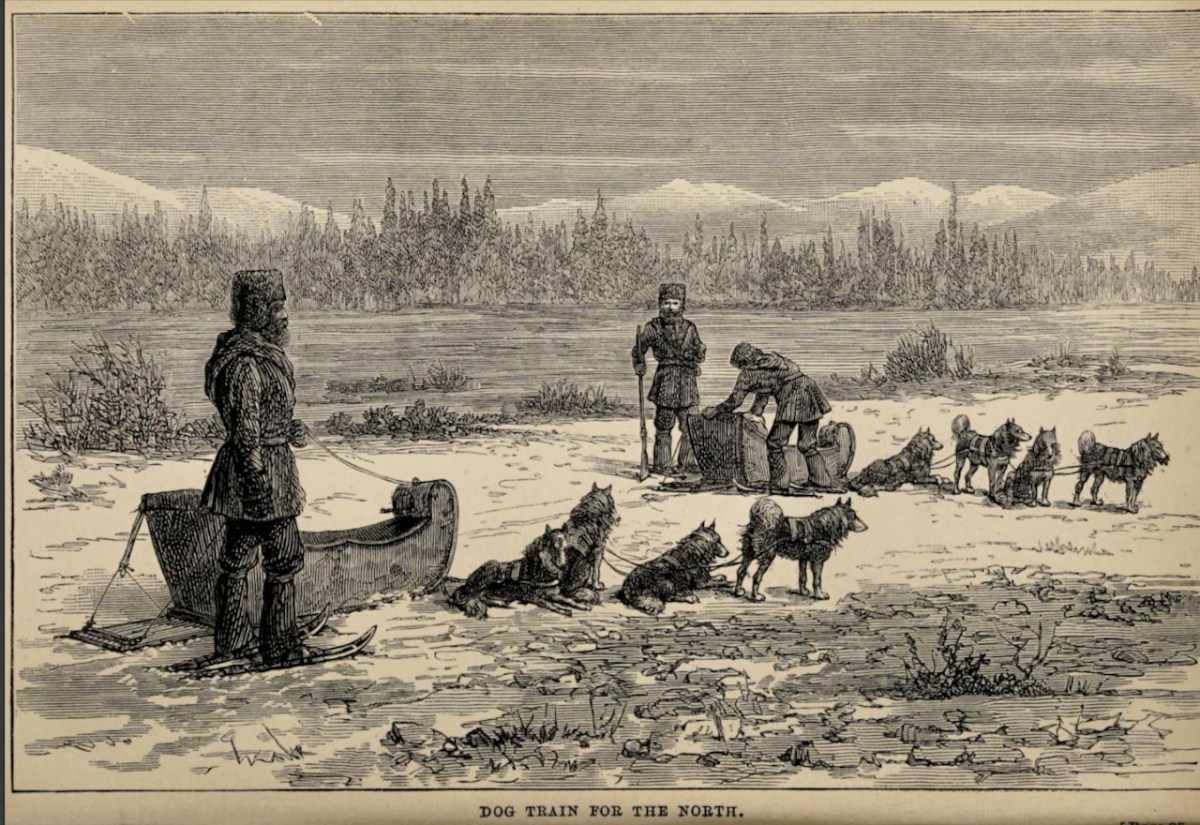

Funeral in Chapel Lane, Skibbereen

However, from the point at which he broke away from the Relief Committee, Fisher seems to have been in conflict with his Catholic clerical counterparts. A typical product of the evangelical movements described in the last post, he was zealously committed to winning souls away from the superstition of Popery. The crux of the matter, of course, is whether or not the aid he provided was conditional on conversion. Many other West Cork Protestant clergymen laboured to alleviate famine suffering, but most remained on good terms with Catholic priests and won praise from them rather than opprobrium.

Fisher’s memorial tablet in Teampall na mBocht

Damning accusation were made by Fr Barrett against Fisher, that his zeal led him to confine his bounty to those of his creed, and to famine-constrained proselytes. He went on to state that when he protested to Fisher, that Fisher had said that had English contributors known that a Popish priest sat on the same seat as himself, sooner would they have cast it away than give a single shilling to relieve those whose religion he himself had sworn to be idolatrous, etc, and which he, in common with English contributors, believed to be the sole cause of blight disease, death, etc.

Also in Teampall na mBocht

Fisher, of course saw things very differently. He denied ever coercing anyone into converting. If he gives only a little charity, he wrote of the fate of Protestant clergymen, he is accused of living off the fat of the land, but if he denies himself and his family to relieve the poor he is publicly reprobated as one taking advantage of the misery of the poor in order to bribe them into a hypocritical profession of a religion that they do not believe. But despite his protestations his reputation among Catholics remained that of a Souper. Perhaps there is no smoke without a fire.

Fisher’s son-in-law, Standish O’Grady (above), whose own father had preceded Fisher as Rector of Kilmoe, wrote about him that, if ever a saintly man walked the earth, he was one. I never saw in any countenance an expression, so benignant or which so told of a life so pure and unworthy and a self so obliterated.

Fisher’s pulpit in Teampaill na mBocht

This is the central dichotomy at the heart of this story. Fisher was a deeply spiritual man, fired up by the desire to do good, as he saw it. The beneficial outcome of this was that, during the worst of the famine, he provided food and employment for hundreds, and saved probably thousands from death. He stayed in Kilmoe until his own death in 1880 – ironically from famine fever contracted during another, although less catastrophic, period of famine – and continued to labour tirelessly for his flock.

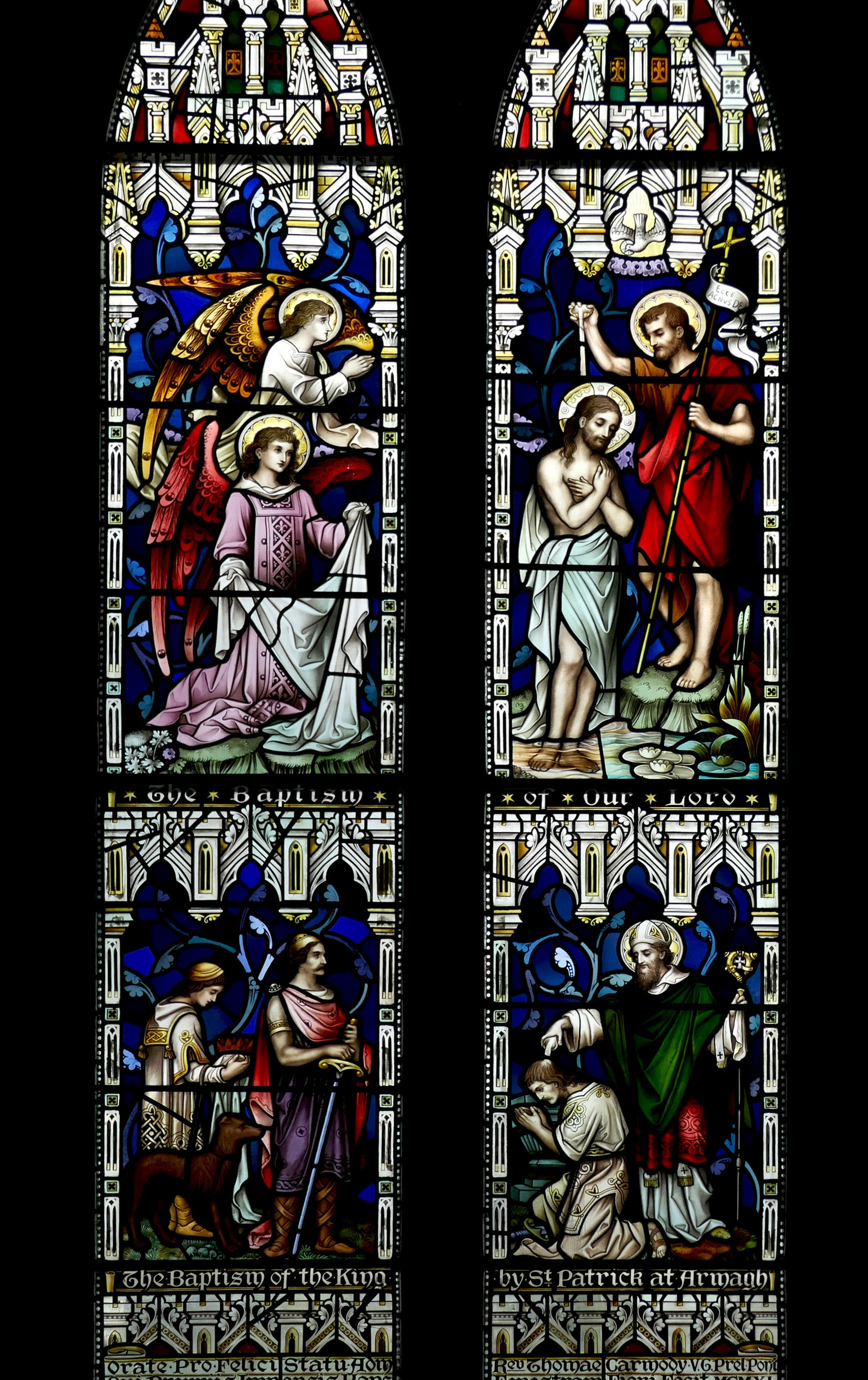

Fisher’s memorial window in the former Church of Ireland church in Goleen

If he did indeed administer the bible test as a precondition of aid, he did so in the honest and total conviction that what he was offering was true salvation, an escape from the worst excesses of Popery. In this, he was no different from the zealots who galvanised into action to win back those souls for the Catholic Church. In the next, and final (whew!) post, we will examine the Second Counter-Reformation that swept into West Cork like the cavalry coming over the hill, to set Kilmoe and its converts back on the true path – the path back to Rome, in fact.

St Brendan’s Church of Ireland, Crookhaven. One of the Kilmoe churches, still with no electricity

The black and white line drawings used in this post are from the Illustrated London News, mainly by James Mahony, a Cork artist contracted by the ILN to produce drawings of famine conditions in Ireland.

This link will take you to the complete series, Part 1 to Part 7

Email link is under 'more' button.