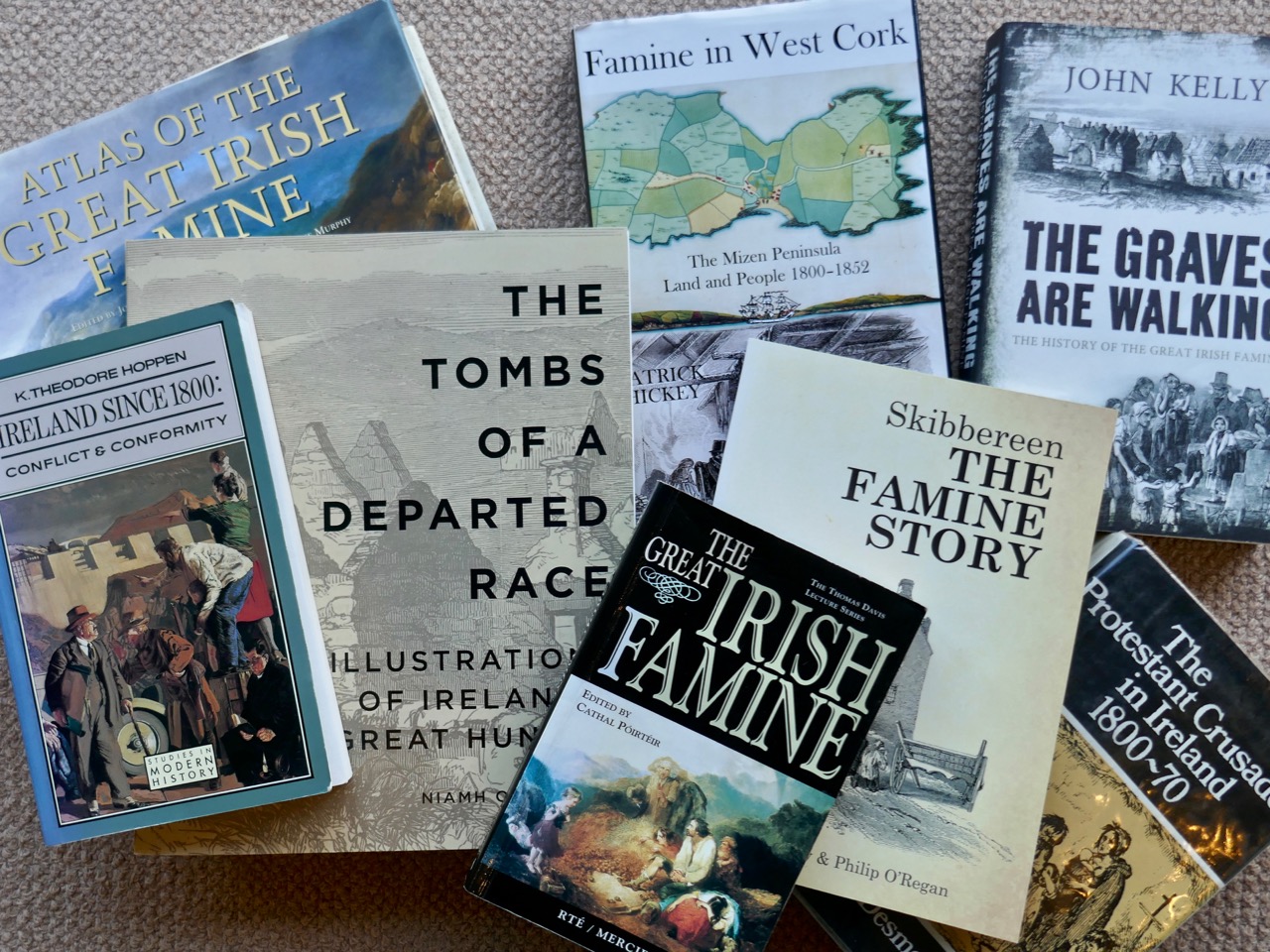

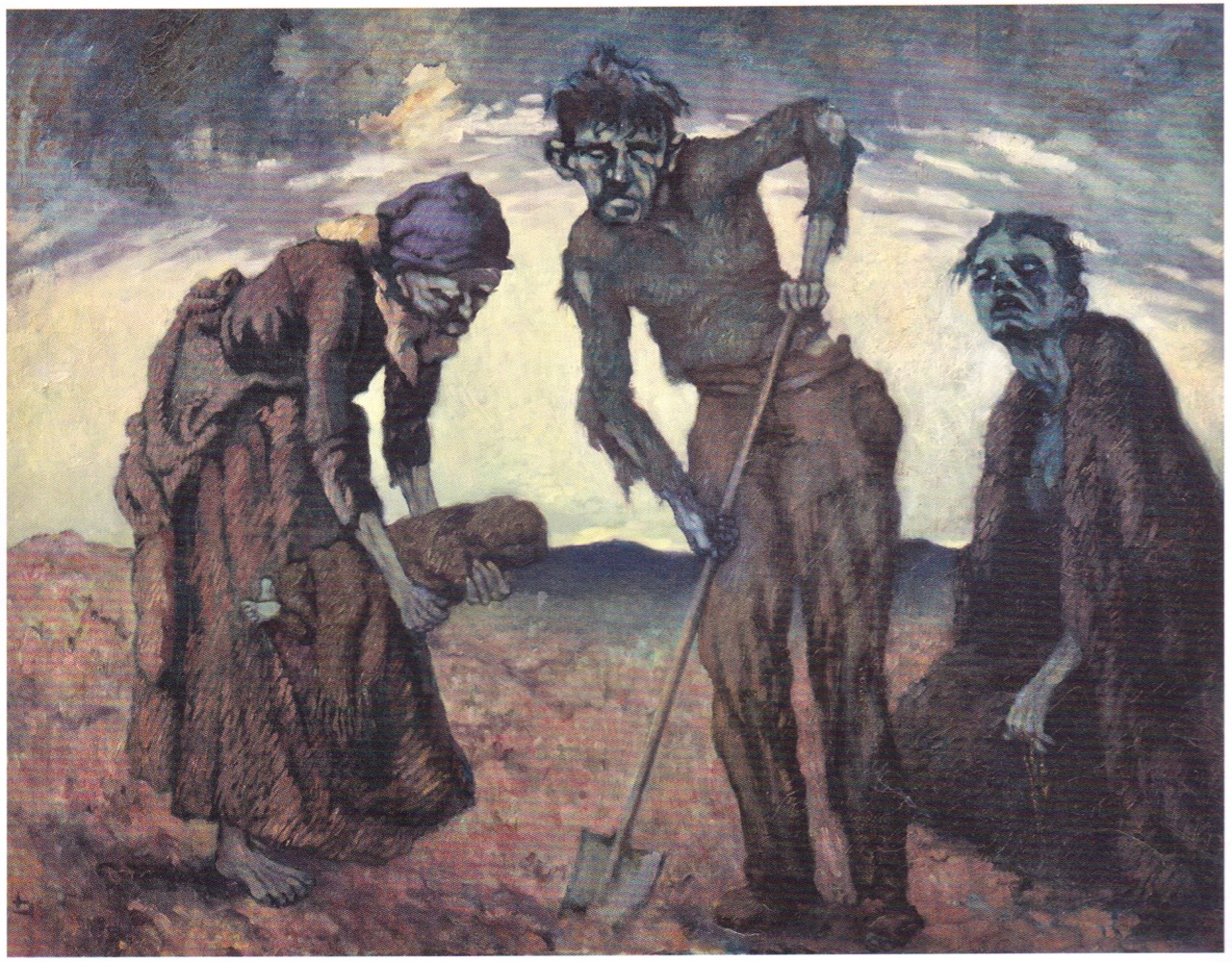

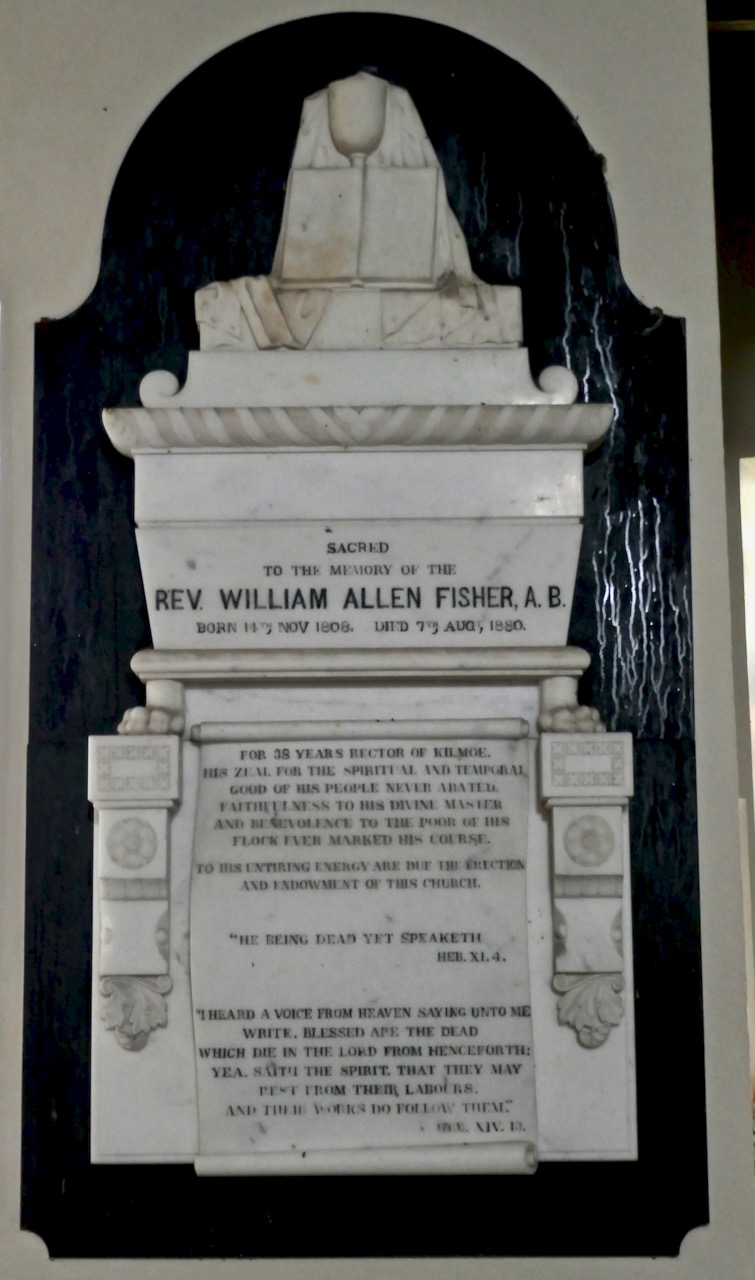

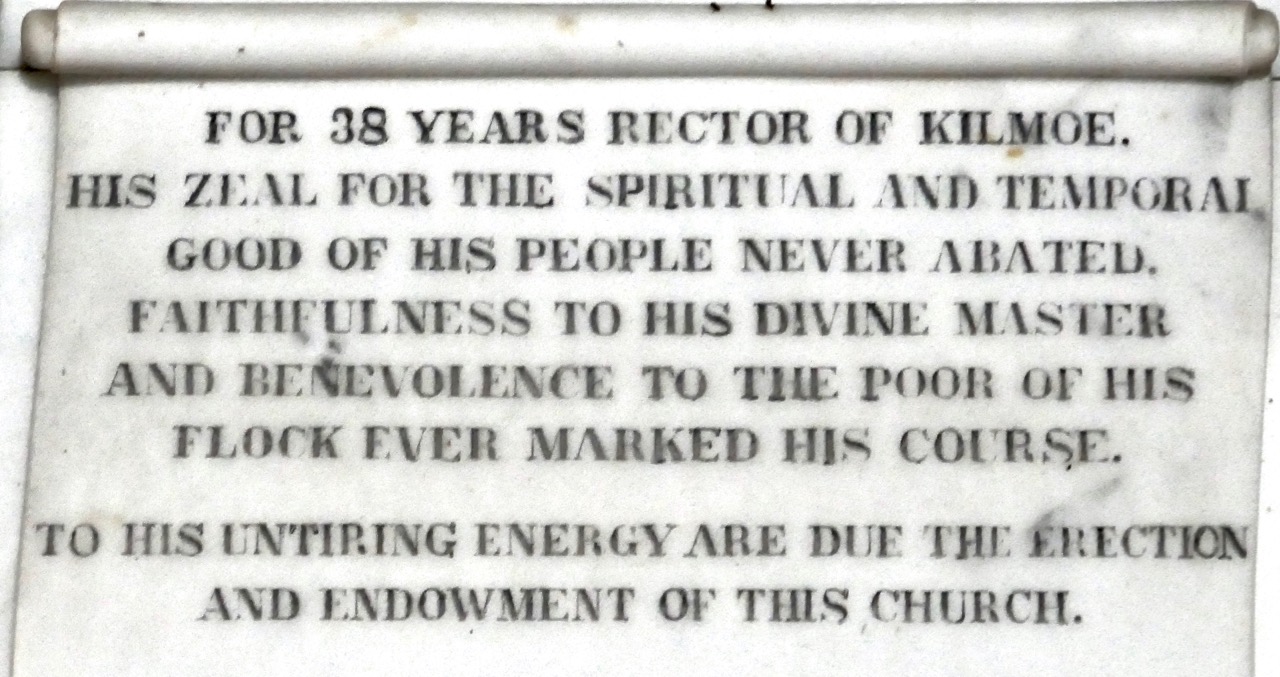

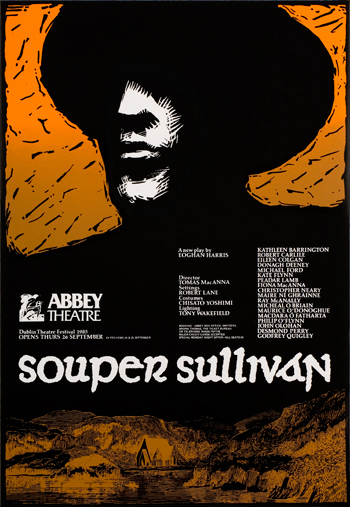

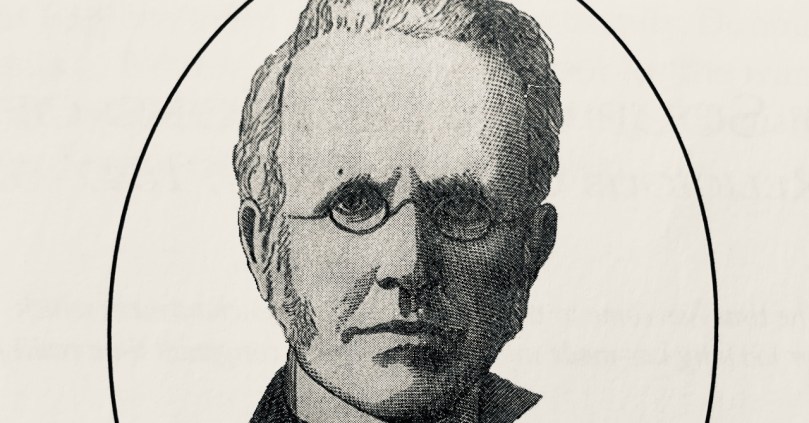

Over the course of a marathon seven posts, I wrote about the Rev William Allen Fisher, revered by his kin and congregation as the energetic and saintly saviour of hundreds of famished souls during the Great Hunger, and reviled by his Catholic clerical counterparts as one of the worst examples of a Protestant Clergyman who bought conversions with food and employment. Balanced precariously on the fence of fairness, I concluded that he was both a Saint and a Souper, conflating, as he did, the imperative to feed the body with his mission to save souls.

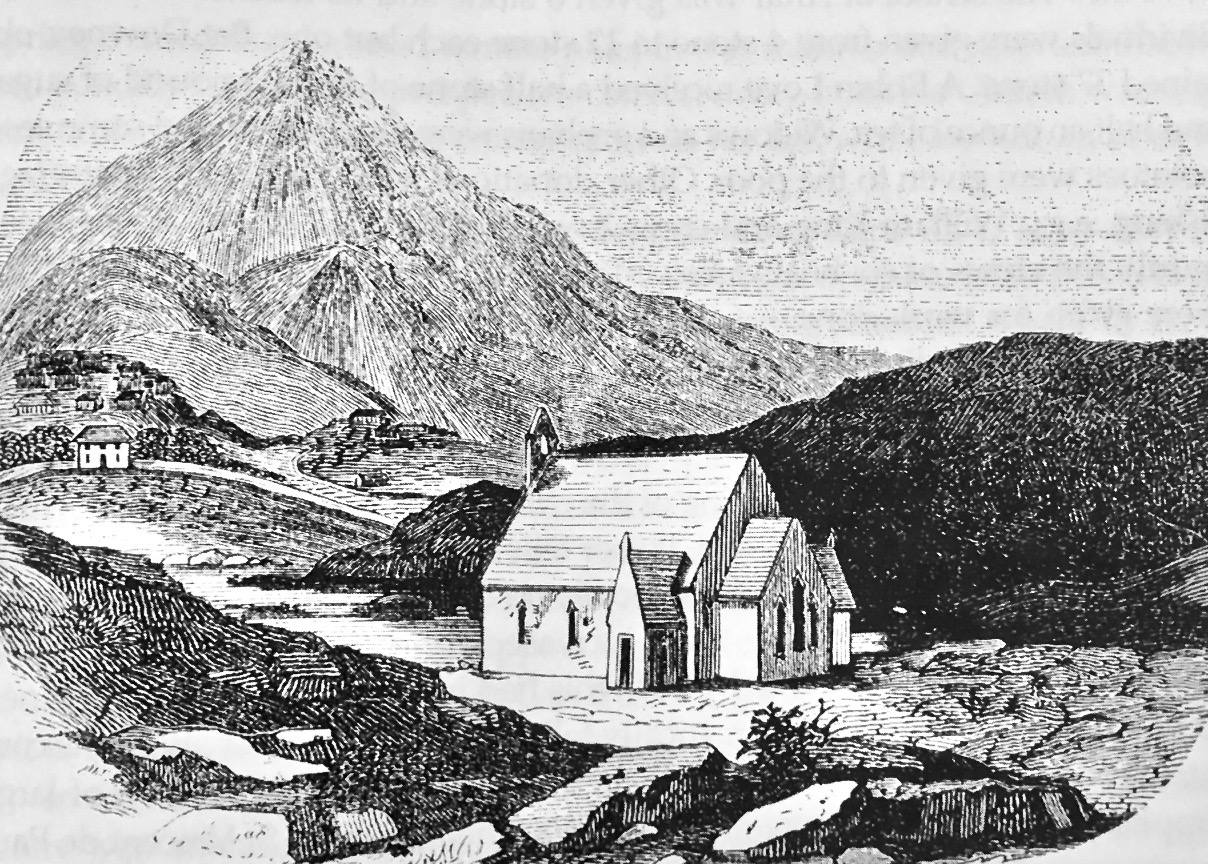

Paul Farmiloe’s lovely sketch of Fisher’s church, Teampall na mBocht in Toormore

It is difficult to overstate, from this remove, how normal his kind of evangelical Protestantism was for the time in which he lived and worked. Ultimately, though, he was on the losing end of history. Not only did the Protestant Crusade, of which he was an enthusiastic proponent, fail to convert broad masses of ‘Papists’ but the burgeoning social and economic power of the Catholic Church ensured that those individuals who had converted to the Church of Ireland felt the full might of episcopal condemnation. Indeed, to be accused of being a Souper remains to this day one of the worst insults that can be said to an Irish person.

In this church-dominated narrative, which all of us were fed in school in the 50s and 60s (betraying my age there – and I am in that blurry photo above), there was no room for allowing that a conversion to the Church of Ireland could possibly be through genuine conviction or a change of heart. No, such conversions – or perversions as they were labelled at the time – came as a result of taking advantage of people driven mad with hunger. Knowing as we did that Catholicism was the one true faith, how could we accept that anyone in their right mind could abandon it? It’s always been interesting to me, by the way, that at the same time as we were taught to excoriate those who converted away from their own faith, we were happily offering up our pennies to fill the collection boxes that every school had for Ireland’s extensive Missions Programs, in which Irish priests and nuns (including members of my own family) spread out across the world with the intent of wresting souls away from other religions.

In the second half of the 1930s the Folklore Commission collected stories and local traditions from over 50,000 schoolchildren in Ireland (like the boys in the 1930s classroom above) – now all available online. I was curious whether stories of the Rev Fisher had persisted in local memory and I turned to this collection to look, specifically to the schools in the vicinity of Toormore. And yes – here it all was, occasionally in remarkable specificity, still very much alive ninety years after the events had taken place.

Mary O’Sullivan from Toormore National School contributed this detailed piece:

The only landlord that any of the old people around here heard tell of were Mr Baylie and Mr Fisher. Although a Protestant, he was a very good man, and all his tenants were catholics, in fact the Catholic curate of the parish was living in a cottage on his lands – where Mr Hogan now resides. All his tenants were living in peace and comfort until he was forced to sell all his property to the church body, one of whose agents was a minister named Mr Fisher.

The first act that he did was to issue notices that any catholic that did not pay the running half gale within a month would be evicted. All the catholics paid, and the next notice issued intimated that any catholic that did not go to church on the following Sunday would be evicted.

Some of the catholics remained steadfast, but as Fisher had the law in his own hands he had no trouble in evicting all those who he knew had the best of the lands. Those farms he divided into smaller lots, and gave to those whom he got to go to church.

There were two catholic schools in Toormore at that time, one for boys and the other for girls. These were closed so that the children should go to the Altar Protestant school. As the time went on the people got poorer as a result of evictions, and Mr Fisher keeping constantly going amongst the poor people with his charity and prayers he got some of them to go to church to save themselves from starvation. But others endured the greatest privation and kept the faith. Some of these that were evicted were given houses by their old landlord Mr Baylie.

Mr Fisher was supposed to have contracted what was called a slow fever, he was taken from the Altar to Dublin where he died.

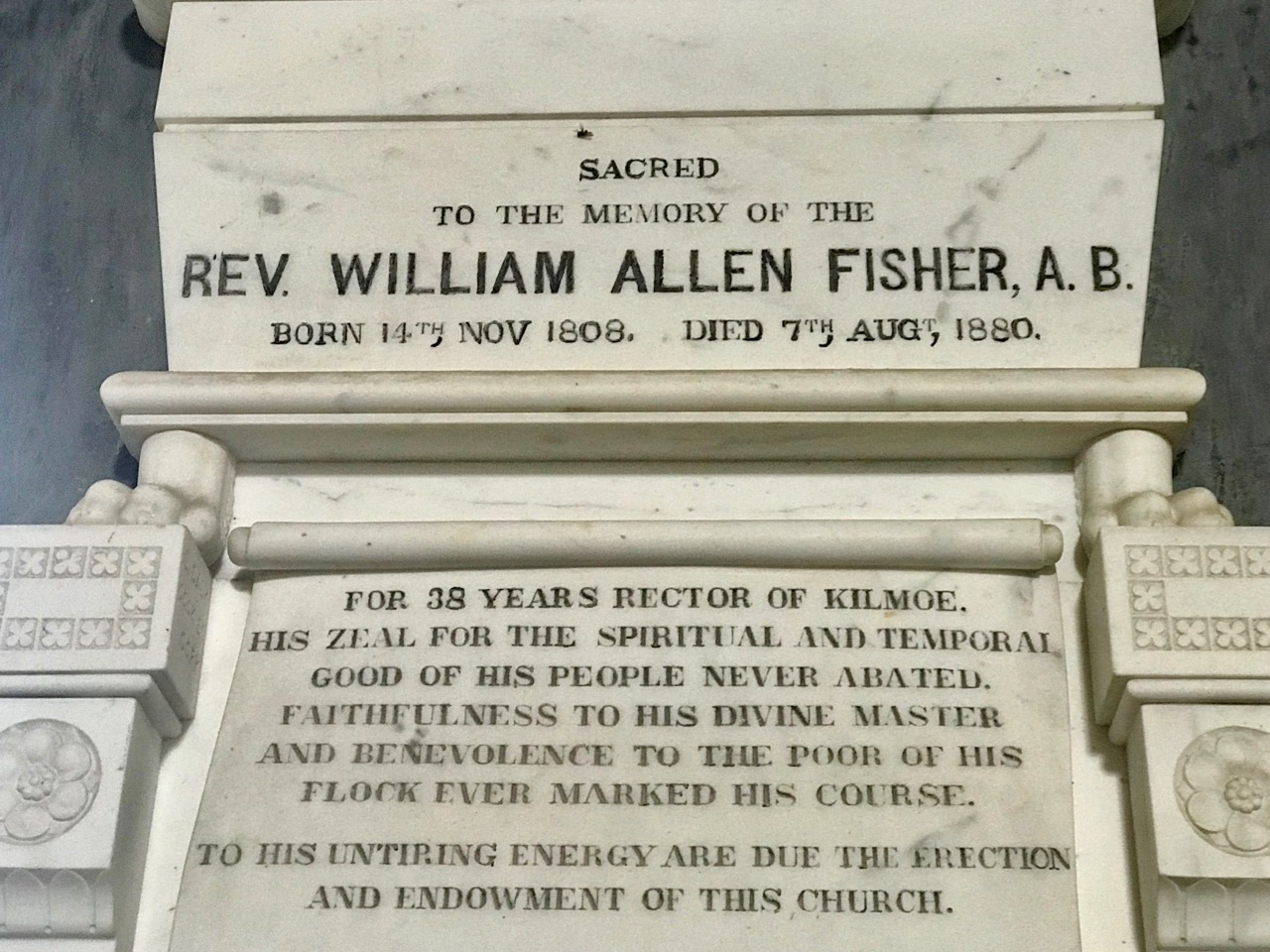

I found that last paragraph interesting as I know that Fisher is on the same headstone (below) as his brother in Mount Jerome Cemetery in Dublin but had been unable to find any account until now as to why he would not have been buried in his own churchyard in Goleen. I also need to point out that there is no evidence, or accusations in contemporary accounts, that Fisher evicted tenants or used eviction or a threat of eviction to force conversions. Finally, if anyone knows what a ‘running half gale’ refers to, do let us know as I have been unable to track down the term.

Eileen O’Driscoll, also of Toormore, had this version

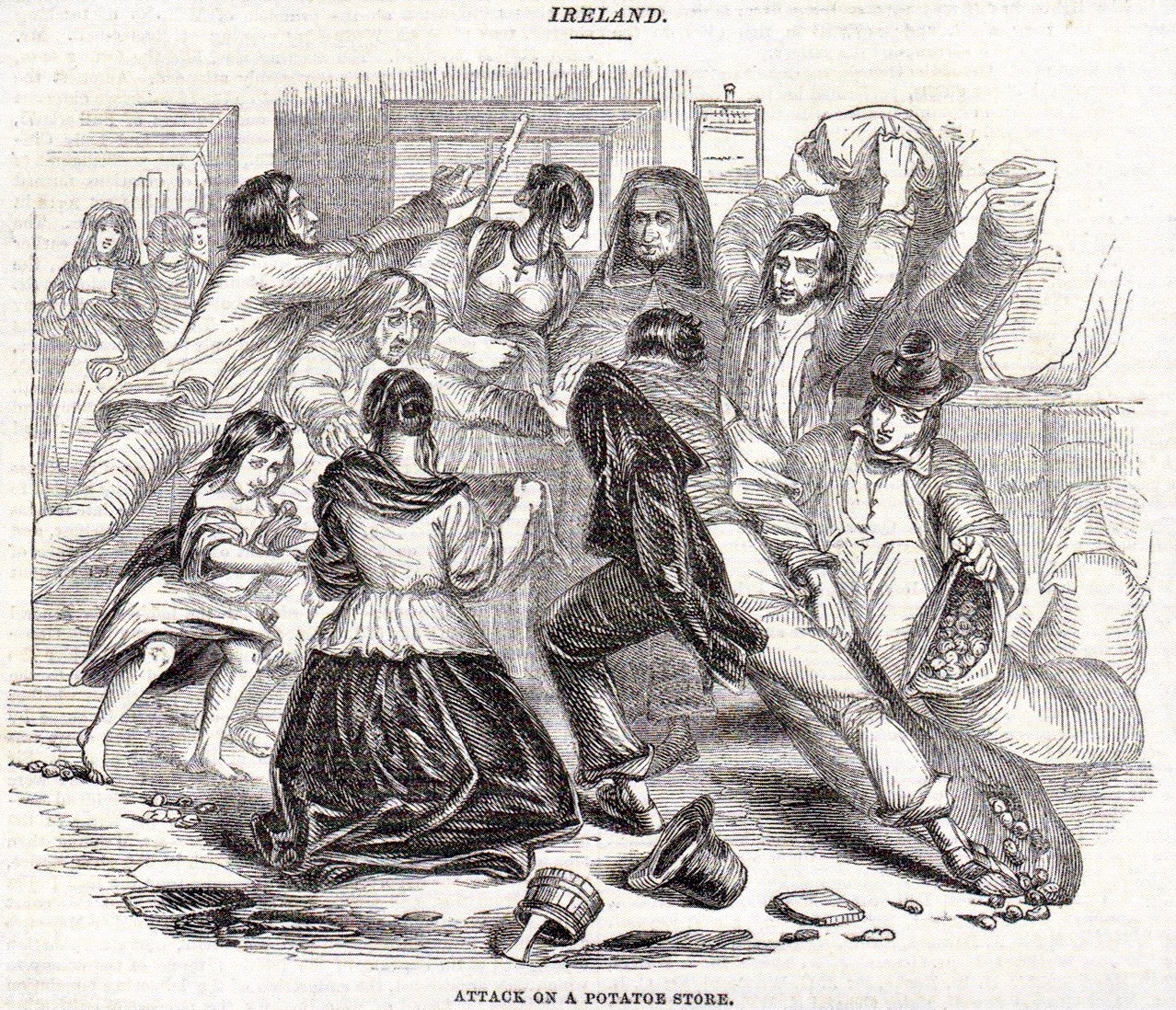

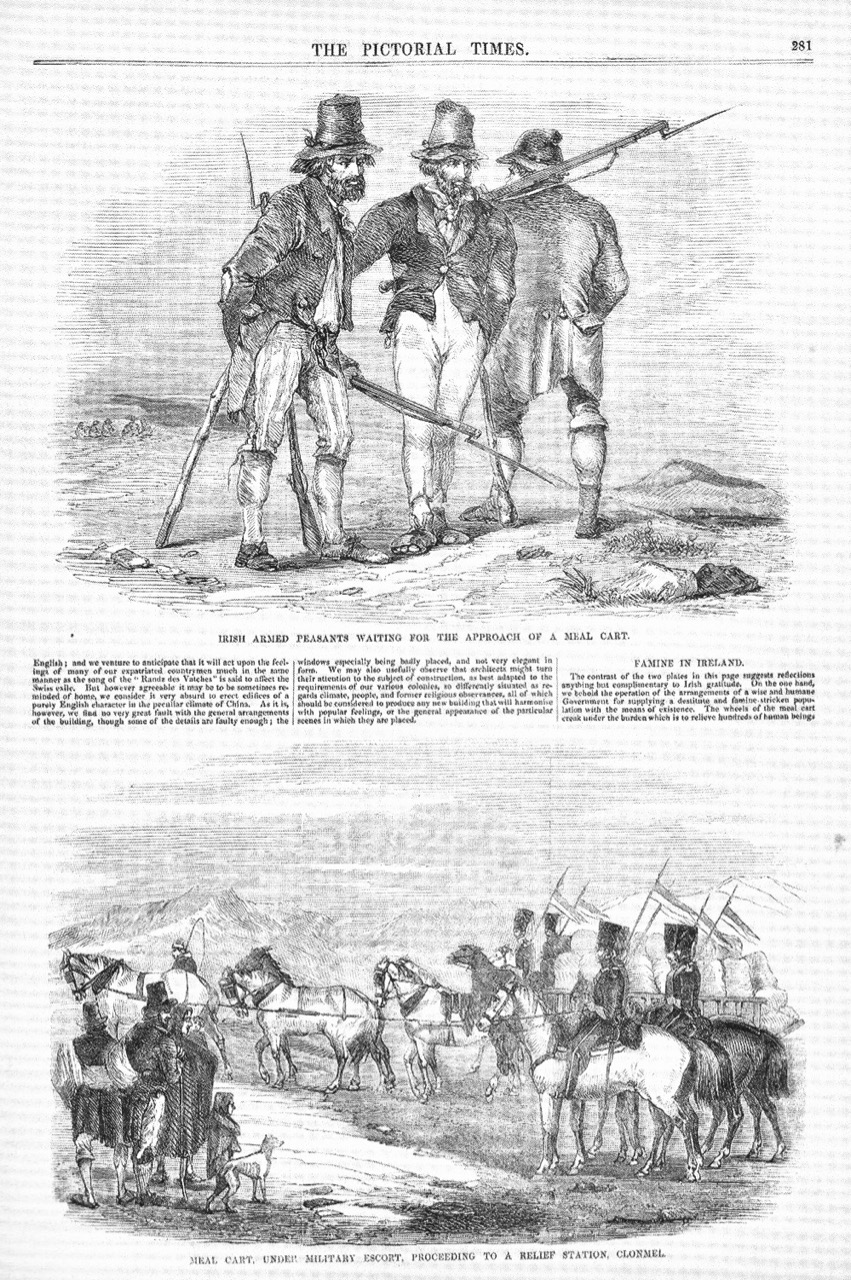

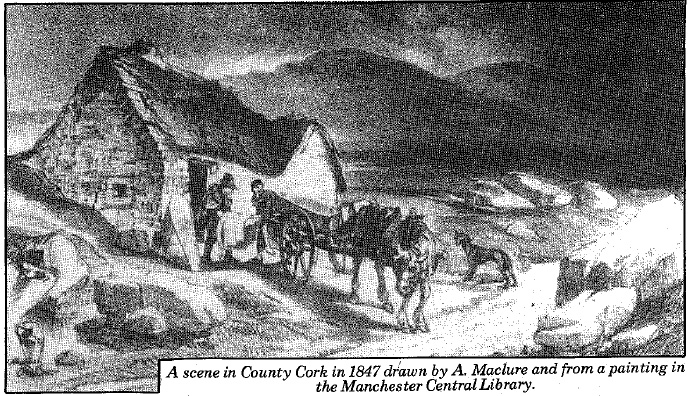

The famine years lasted from 1845 to 1847. In this district the people had plenty of corn but they had to export it to England to pay the rent and the potato crop failed. The potato was their principal food for breakfast dinner and supper. Lots of them died of hunger and the fever came all over the county and swept them in hundreds. There were men hired for carrying them to the nearest burial ground which was Kilhangil. They had a special car for that purpose. They called it a bogey car. This man carried nine or ten at the time and dug a big hole and covered them over without any coffin. There was then a relief sent from England to all Parish priests and ministers. In this parish the the minister took hold of the clothes that were sent and some of the poor Catholics died of hunger before they would take anything from the Protestants and others took the clothes and turned Protestant. Mr Fisher was the minister of this parish and also the landlord of Toormore and Gorttyowen. He got the clothes and distributed them to anyone that went to the Protestant church on Sunday. Many Catholics availed of this offer and they were called “soupers or turncoats” The Bishop became angry and he sent a very strict priest to the parish. His name was Fr. Holland. He gave very harsh sermons to the people and we are told that when Mr Fisher got up on Monday mornings he found lots of clothes outside his door. A lot of the people still kept on getting the clothes. Fr. Holland said that he would curse the people that went to the protestant church. He got permission from the bishop to do so. One Sunday as he was speaking in Ballinaskeagh Church a man stood up and said he would go in spite of any Bishop to what churches he like himself. The man died before the end of that day, and his son was killed by his own horse within a week. This frightened the people and it forbade a great number from attending the Protestant Church any more There was one man in Toormore that went to the Protestant Church but he also went to Mass before going there. Mr. Fisher found this out. He met him one day and asked him why he was going to Mass and also going to Church He said he was going to Mass to save his soul and that he was going the Church for to save his body Mr. Fisher bought Mr. Bailey’s property which was Toormore, Gorttyowen, and the Altar. He evicted all the Catholic out of Gorttyowen Toormore but left those that remained souper in their holdings and they are known as Toormore soupers.

There is so much to unpack here. In this version of the story the main inducement to convert is the provision of clothing, rather than food. In Saints and Soupers Part 6 I related that Bishop Delany of Cork had sent the firebrand Fr John James Murphy (AKA The Black Eagle of the North) to sort out the situation and he had succeeded in winning back (or browbeating) many of the converts. There was indeed a Father Timothy Holland in Goleen, but it was several years after the Famine, from 1863 to 1867, and his fierceness and effectiveness has obviously lived on in folk memory and become intertwined with that of Fr Murphy. (Perhaps it was Fr Holland who lined up all the newly married parishioners and married them again in case they hadn’t been ‘properly’ married the first time – see the comments at the end of Part 7.)

The story of the man who asserted his independence of choice only to be struck down, along with his son, is a trope of many Irish stories, often revolving around the wilful destruction of a fairy fort or a holy well. Finally, Kilhangil, nowadays a particularly beautiful and peaceful spot (below), may be familiar to you from the post Mizen Magic 19: Church of the Angels

A pithy entry from Mary Lucey of Ballyrizard relates information from her father, Tim.

Mr Fisher was landlord of Toormore. He was a very bad man and he hated the Catholic Religion. All Catholics who would not become Protestants were evicted. Most of them kept the faith but some turned Protestants for the sake of keeping their land.

Once again, eviction takes centre stage, this time as the outcome of refusing to turn Protestant. Hating the Catholic Religion is equated with being a very bad man.

Kathleen McCarthy from Lowertown School (that’s Lowertown townland, above) wrote about many aspects of the Famine, including this section on Fisher.

The famine times were from the beginning of eighteen forty seven to the end of eighteen forty eight. The conditions of the Catholics was terrible at that time. Their potatoes were destroyed with the blight, and they had to sell their wheat to pay the rent. In this district three quarters of the people died with hunger.

The English sent yellow meal to the Protestant minister in Toormore to distribute among the people but it was the Protestants who got the most of it. Any Catholic who would turn a Protestant would go to the minister’s house every day and they would get a bowl of soup to drink and meal to take home. Nearly every Catholic in Toormore turned Protestant in that time and their descendants are there today, Protestants and bearing Catholic names. Toormore is known as “the land of soupers” on account of the number of people that turned Protestant for a bowl of soup. There lived one man in Toormore called John Barry and he had seven children. Six of the children died with starvation and he would not go to Fisher for anything for them.

This is the first account we have of Taking the Soup, and the labelling of Toormore as ‘the Land of the Soupers’. The story of the man who would rather let his children starve to death than take the soup is a familiar one. While these John Barrys were held up, in our history lessons, as a model of steadfastness and an exemplar of Catholicism, I remember being horrified that any father would act in this way. Perhaps it’s one of the thousand little cuts that eventually ushered me out of the church.

A cloakroom in a traditional schoolhouse

Annie Donovan collected information from Jeremiah Donovan of Gunpoint who was 97 when he was interviewed. There is a long and detailed description of the conditions and burial practices during the Famine, and it includes this short piece:

The Catholics were starving with the hunger and Fisher who lived in Toormore at that time gave meal and soup to any Catholics that would go to him. Nearly every person in Toormore went to him for the soup and yellow meal, and they turned Protestants also. They were called “Soupers” and the village of Toormore was called “The village of the Soupers” since and their descendants are still living in Toormoor with Catholic names.

This is a particularly interesting account, since Jeremiah would have lived through some of the events he relates, as a young boy. There is also the same reference as in Kathleen McCarthy’s essay to ‘Protestants with Catholic names’ – a poignant reminder that in Ireland one’s last name is often a pointer to one’s religious affiliation.

Peter Clarke’s beautiful sketch of the church that Fisher built at Toormore, also called the Altar Church and Teampall na mBocht (Church of the Poor)

A long but anonymous entry from Gloun School (on the slopes of Mount Gabriel – the old school house at the end of this post is associated) goes into great detail about various aspects of the Famine, mainly centring on evil landlords, and contains this:

At the time of the famine, some Catholics turned Protestants. They became perverts to get soup which the Protestants minister gave out. The name of the minister of Toormore was Mr. Fisher.

Some of the “soupers” were William O Donovan and John O Donovan both natives of Toormore. William O Donovan’s daughter, Mrs Coughlan, still lives in Corthna. John Donovan’s grandson is a shop-keeper in Schull, whose name is Joseph Woods. Another man who was a “souper” was Joseph Daly, a native of Toormore. He afterwards became a minister. Before he became a “souper” he was so holy it was said that he could walk upon the waters. He tried to do it once, before a crowd but he sank. He also answered Mass in Ballinashker Chapel barefoot once. His son lives in Schull. Ever since Toormore is sometimes called “the land of the soupers” and the Protestant Church is called ” Teampall na mboct” which means”the Church of the poor”.

I think this piece, more than any other, is illustrative both of the long memory of these events and of the classroom ethos of devout Catholicism in which this child writes – an atmosphere in which it has been normalised to name and shame the ‘Soupers’ and their descendants several generations on. This is divisive sectarianism at its most abhorrent, and it’s just as important to understand this, as it is to chuckle at the funny verses and old folktales that the children also write about.

The old school house at Lissacaha near Gloun

There’s more, but I think this gives you a flavour. Rev William Fisher has left a complex legacy. Some of it springs from his own actions – we haven’t exonerated him from bigotry and over-enthusiastic proselytising (another possible future post, in the light of new information). But it’s also based in the narrow, blinkered, self-righteous Catholicism that encouraged the condemnation of neighbour by neighbour, in the name of religion. It would be good to think we’ve moved beyond that now, in Ireland.

This link will take you to the complete series, Part 1 to Part 7