Loher Fort was excavated for four seasons in the 1980s by an archaeologist from UCC. Yes, that’s right, four seasons! You might reasonably expect, therefore that this would be the fort that would yield a thick report full of details and illustrations of what was found, some radiocarbon dates, some historical context – but shockingly, the only report ever forthcoming was a few paragraphs provided to Excavations.ie. I quote it in full now.

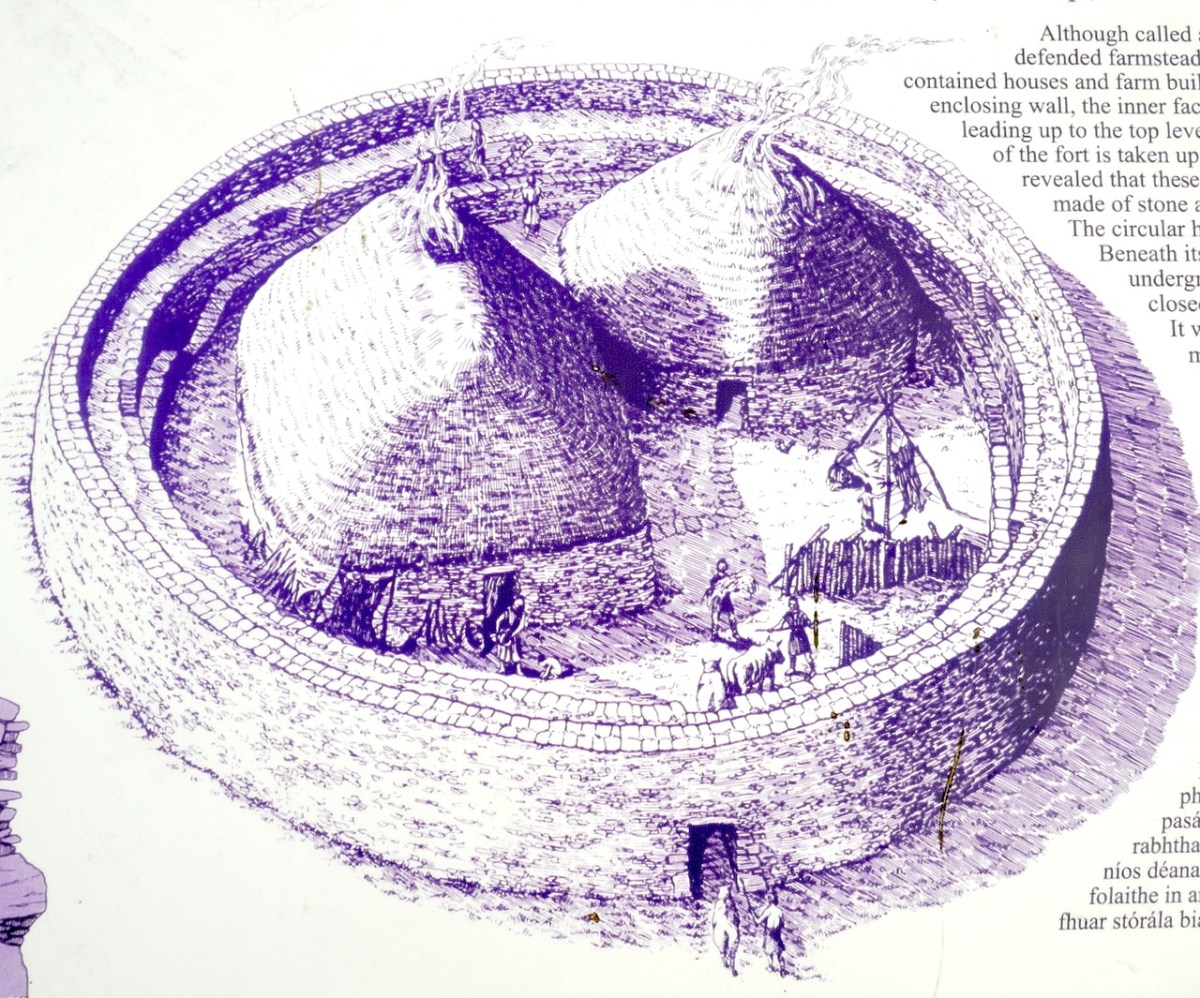

The fourth season of excavation was completed during 1985. The site may be classed as a cashel, 20m in internal diameter, with rampart walls, 2m thick.

Prior to excavation the interior of the site was composed of stone fill to a depth of 2m. On removing this fill, 2 stone structures were uncovered. Both of these had walls surviving to a height of 1m and 1m in thickness. One structure is circular (clochan type) and the other rectangular. The circular structure is c. 5m in diameter and the rectangular structure is 7m x 6m in extent.

The interiors of both these structures have been excavated. This revealed no great depth of occupation deposit but did reveal a good stratigraphic sequence of structures. Essentially, there are 5 identifiable structures including the above two. In the area of the surviving circular structure, an earlier stone-built circular structure was uncovered. This was pre-dated by a wooden structure constructed of driven stakes.

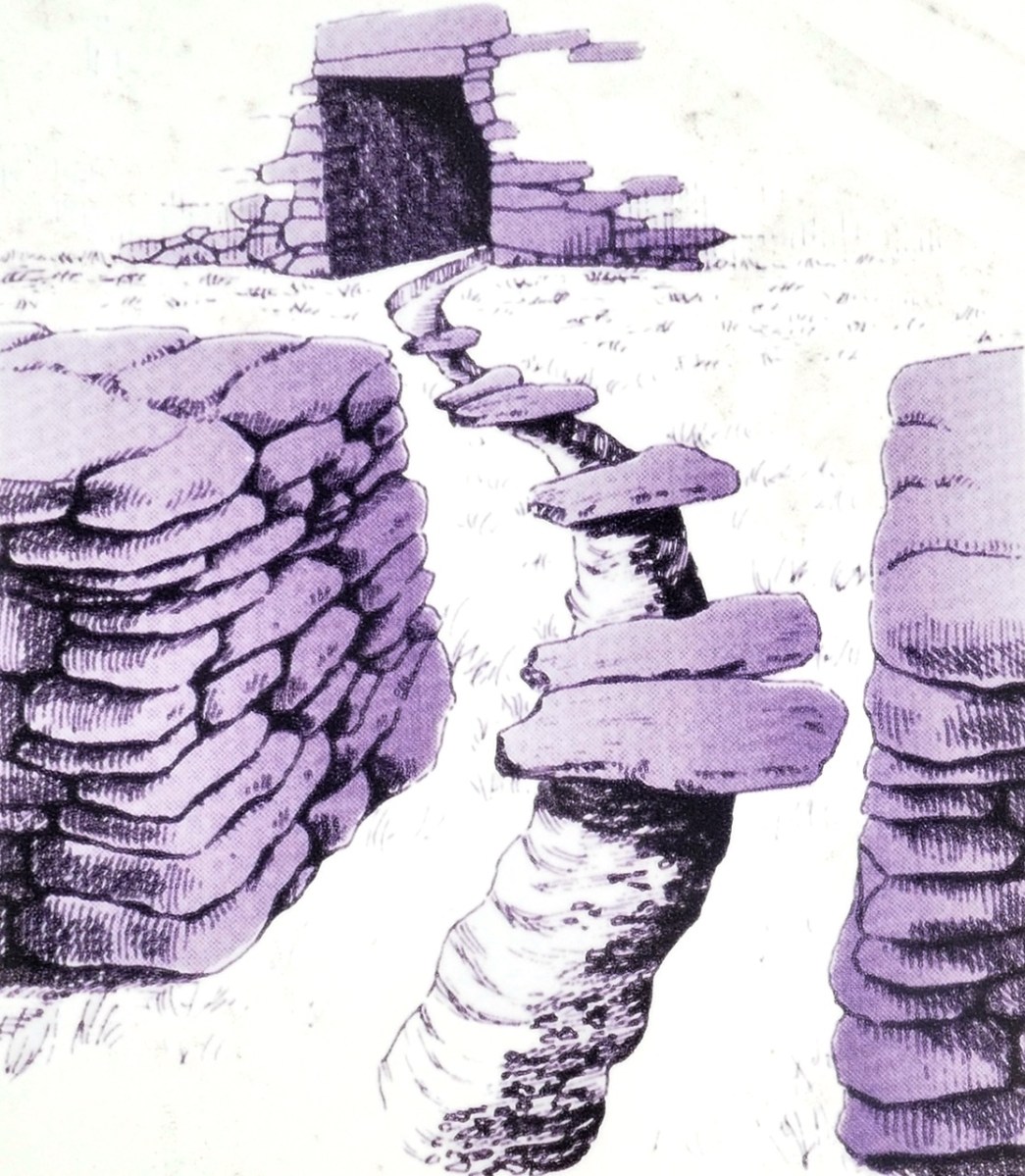

The rectangular structure was pre-dated by a circular wooden house, again of driven stakes. There is also the possibility of another post-built structure in this area. Apart from the above mentioned stratigraphic relationships, the latest circular structure pre-dates the rectangular stone structure. Other features include a souterrain associated with the circular house, and a parapet walkway and mural steps.

Finds include glass beads and a tanged knife. Organic material includes shell, carbonised seed remains, fish scales and fish bones.

https://excavations.ie/report/1985/Kerry/0000602/

That’s it – that’s all we know, apart from a very broad assigned date in the overview of Medieval (AD 400-AD 1600).

Interestingly archaeologist Aoibheann Lambe, the rock art expert, has identified a number of pieces of rock art in an around the fort, including on stones used as building materials. While these pre-date for fort by several thousand years, it is evidence that people were living in this area for millennia. It’s easy to see why – it’s a spectacular setting, with access to the sea and a location that provides a strategic point of domination over the surrounding landscape.

As at Leacanabuaile, there was also a souterrain, although there is no indication on the ground now of where it was, and we have no record of what it looked like and no plan. It was under the round house, which is the earlier of the two houses. Here’s what the National Monuments records says about that:

The entrance to a souterrain is located in the W half of the interior of the house. Measuring 1.1m x 1.3m, it gives access to a drystone-built lintelled passage, 1m high, which runs E-W for 3m before turning sharply to N. The excavation revealed that the construction of the souterrain post-dated that of the house, and that an earlier stone-built circular structure in the area of the house was, in turn, pre-dated by a wooden structure constructed of driven stakes.*

What is a souterrain exactly? As the name suggests, it’s a man-made underground passage, often associated with ringforts and cashels. They may have had a variety of uses, but perhaps the main one was as a root cellar to preserve food. That’s me, above emerging from one of the most famous of of our Irish souterrains, Oweynagat at Rathcroghan. They’re a common class of archaeological monument – there are over 1,000 in Cork and over 800 in Kerry. Folklore is rich with stories of souterrains that stretch for miles, that end up in the sea or in a nearby castle, but alas although we know of complex examples with passages leading to multiple chambers, most are quite short and contained within the general area of the ringfort. For more on souterrains, see this wonderful site.

There was also a covered drain leading from the fort entrance to the house, and another between the two houses. Not quite the fine paving that was found at Cahergal, but certainly a way of keeping your feet dry on what were no doubt well-worn paths. There’s no mention of this in the brief report, but obviously the OPW, who conducted the reconstruction, knew about this, as did National Monuments who commissioned the interpretive plaque. Is there, in fact, more information available somewhere? I would be happy to stand corrected.

The walls and stone steps, which are a standout feature of these Kerry Cashels, are described in the National Monuments record. Note they use the word Caher instead of Cashel – both mean ‘stone fort.’

Caher Wall: This consists of a rubble core faced internally and externally with random courses of well-built drystone masonry. Much of the external face, which is battered, is concealed by a substantial build-up of collapse and field-clearance material. The wall, which is up to 4m in basal thickness, varies in external height from 1m to 2.5m and internally from 2.5m to 3.3m. A lintel-covered paved entrance passage. . . leads into the interior of the site from SSE. A terrace, reached by means of seven inset arrangements of opposing steps, occurs on the internal face of the caher wall at an average height of 1.3m. The arrangements of steps occur at irregularly spaced intervals, and the individual sections of the terrace to which they give access average .6m wide. Traces of a short section of a second terrace, also furnished with steps, occur above the first in the N sector of the wall.*

Because we have no access to a proper excavation report, we don’t know how closely the reconstruction efforts at Loher were based on the findings. However, from the little information we have it seems that what we see now on the ground is a reflection of what was left after multiple periods of occupation, one of which (perhaps the earliest phase) included a house built with wooden stakes.

Like Leacanabuaile and Cahergal, it seems that once the excavation is over, the OPW moves in and ensures that what is left, if it is to be open to the public is made safe for visitors. If that was all they did, we might all, perhaps, be a little less confused now about what these forts looked like originally. But the instinct to reconstruct is strong, as well as the perceived need to tidy up the place, round off sharp corners and keep the grass trimmed to golf course standards. The information plaques the National Monuments folk provide are exceptionally well designed and full of welcome information.

What we can say is that it’s a wonderful site, impressively built and situated, and adds to the sum total of what knowledge we have of how high-status individuals constructed statement dwellings or ceremonial spaces for themselves in medieval Ireland.

- The description is taken from the online inventory maintained by National Monument for all archaeology sites in Ireland, available to search here: