Some intriguing arrangements of stones here – and some enigmatic reporting of their significance as history. We are a long way from West Cork – in fact, over on Ireland’s east coast, among the fine estates of Killiney. We can’t help but search out examples of archaeology wherever we go, and a red dot on the Historic Environment map is always a good starting point, as is anything with an enigmatic name.

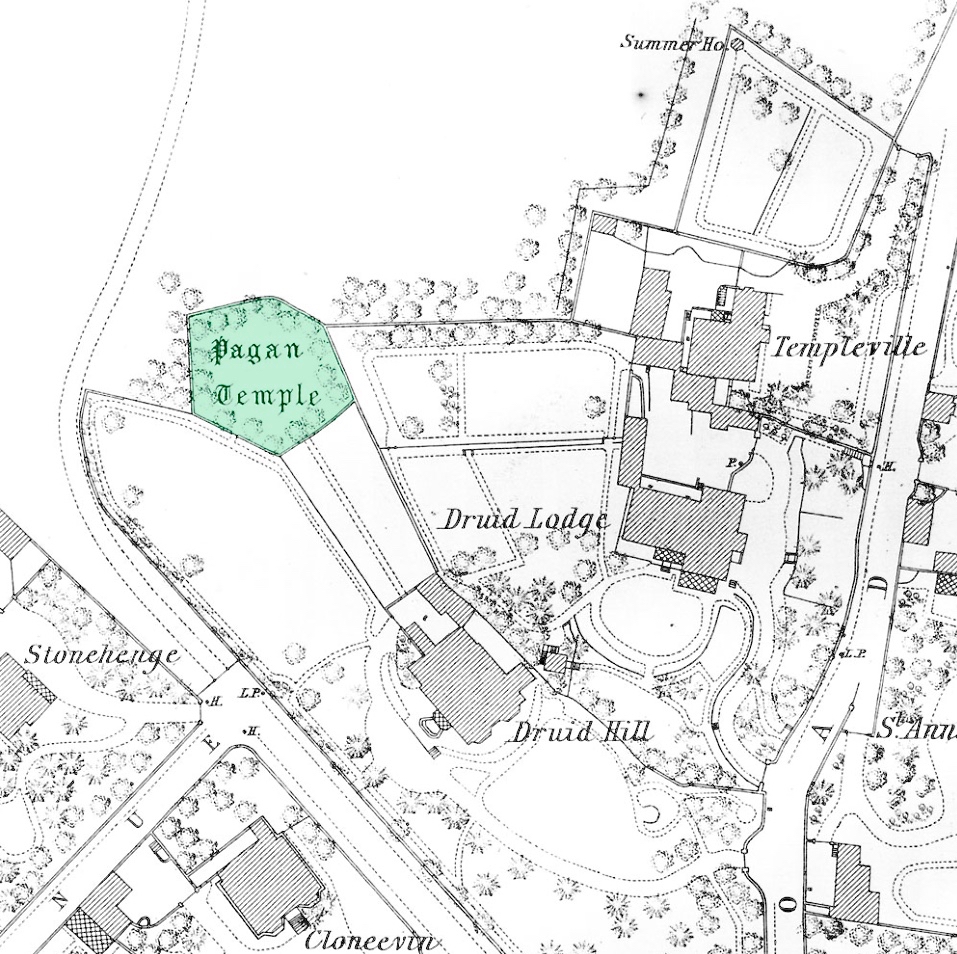

In this case, the red dot is just to the left of the ‘Pagan Temple’ at the top of the 25″ OS map – but look at all the other intriguing names in the locality!

Here’s a close up -extracted from the 1888 OS map, highlighting the site that we are looking at today. With Templeville, Druid Lodge, Druid Hill and Stonehenge as neighbours, the Pagan Temple demands a closer look!

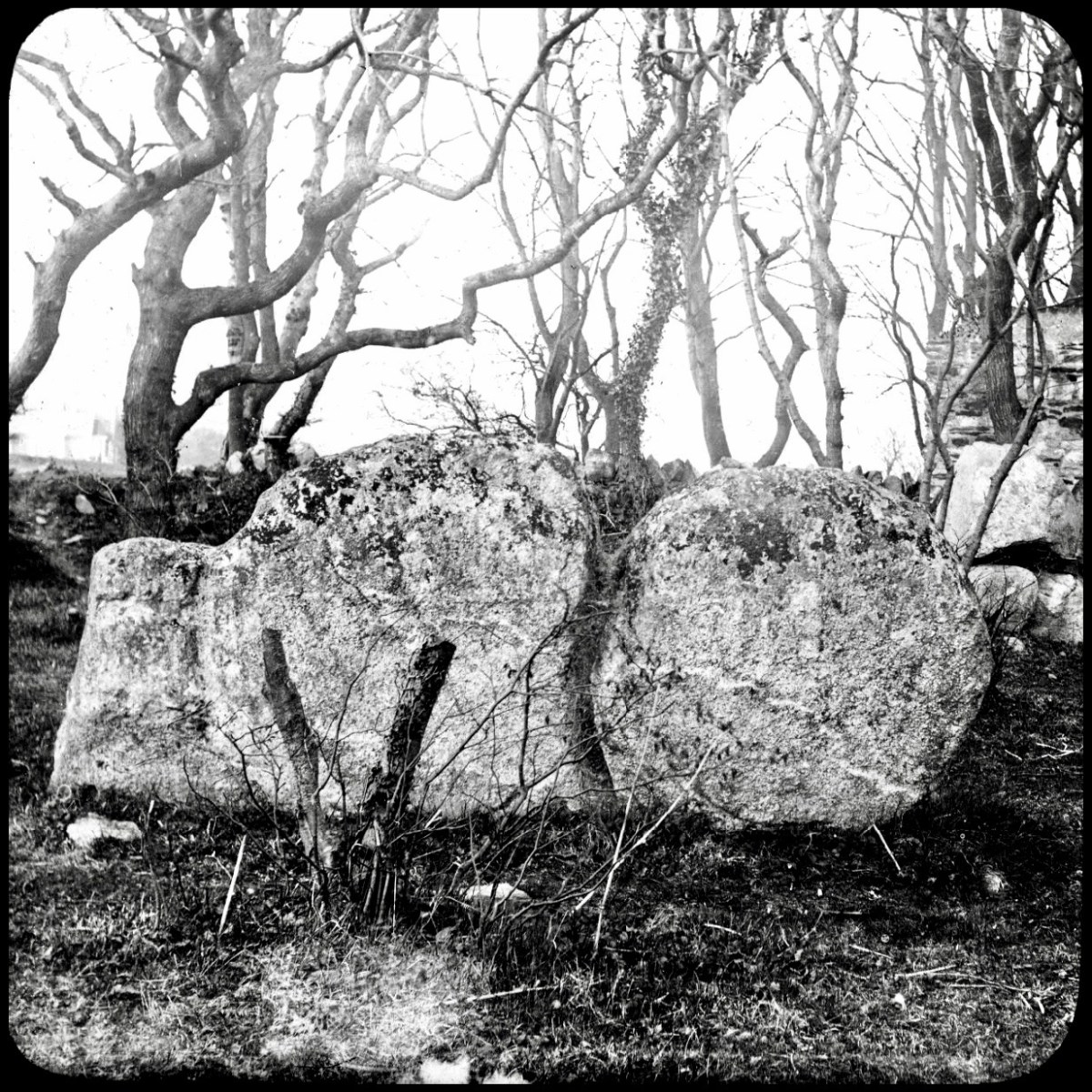

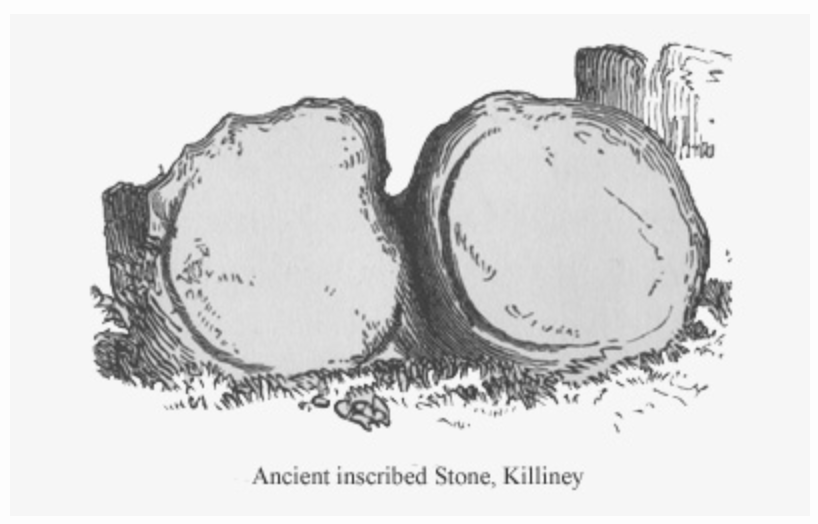

It was last week’s subject – the writer and photographer Thomas Holmes Mason – who directed us to this County Dublin location. As a significant producer of picture postcards, Mason has left a large body of work, even though many of his photographic plates were destroyed in a warehouse fire in 1963. The National Library of Ireland houses a comprehensive collection, and I am grateful to them for this image, above, which shows an intriguing stone formation on the Killiney ‘Pagan Temple’ site. It is referred to as The Sun and Moon stone by some antiquarians, and the following description appears on the current Historic Environment Viewer:

DU026-010—-

Scope note

Class: Megalithic structure

Townland: KILLINEY

Description: “. . .This enigmatic structure is located within an area enclosed by a hedge on top of Druid Hill. In the E side of the enclosure are three irregular granite boulders that form a façade behind which is a larger boulder containing a setting of stones that form a seat. To the W of this are two large granite slabs set on their long axis. There are tool marks present. This structure appears to be a folly but it may incorporate the remnants of an earlier monument . . .”

Archaeology.ie Historic Environment Viewer

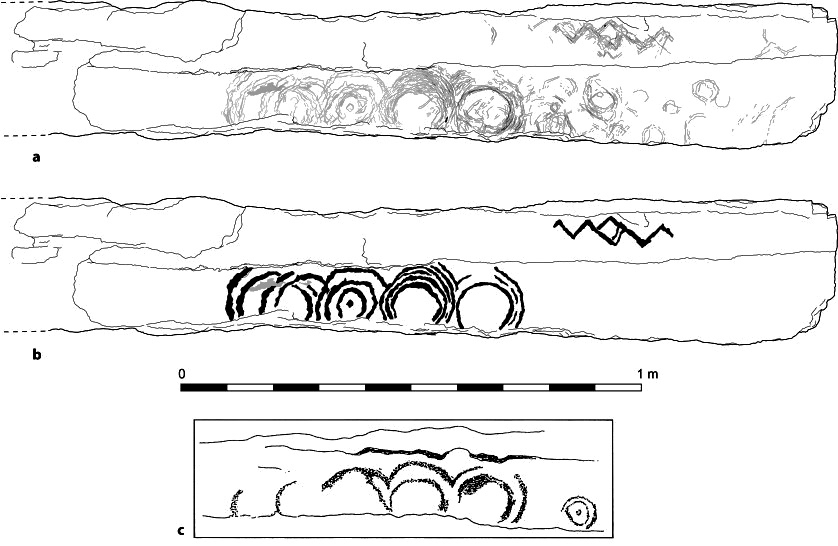

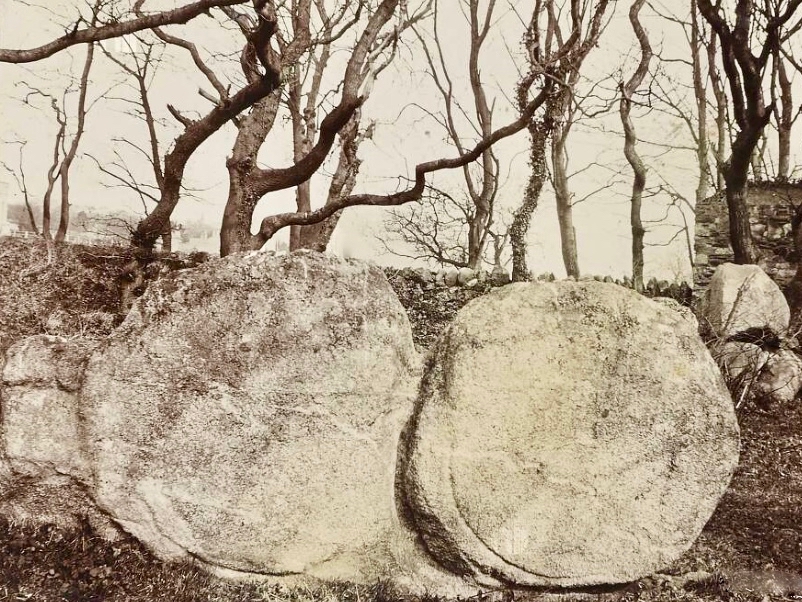

The Archaeology.ie write-up is accurate. In addition to the ‘chair’ (which Finola is elegantly modelling while trying not to sit in a puddle!) there are two further irregular granite boulders – but one of them (detailed in the T H Mason photograph) looks like two circles – hence ‘sun and moon’ – but is in fact a single boulder, here seen from the ‘front’ face:

The right-hand side of this stone has some marks carved on it (by human hand) – possibly part of a large circle that outlines this half, while the vertical ‘groove’, central to the boulder, also appears to have been chased out. It’s worth noting as well, perhaps, that there are two small holes drilled on the back face of this stone, one on each side but not aligned on any centre. Additionally, there is also a small hole drilled on the back face of the second stone:

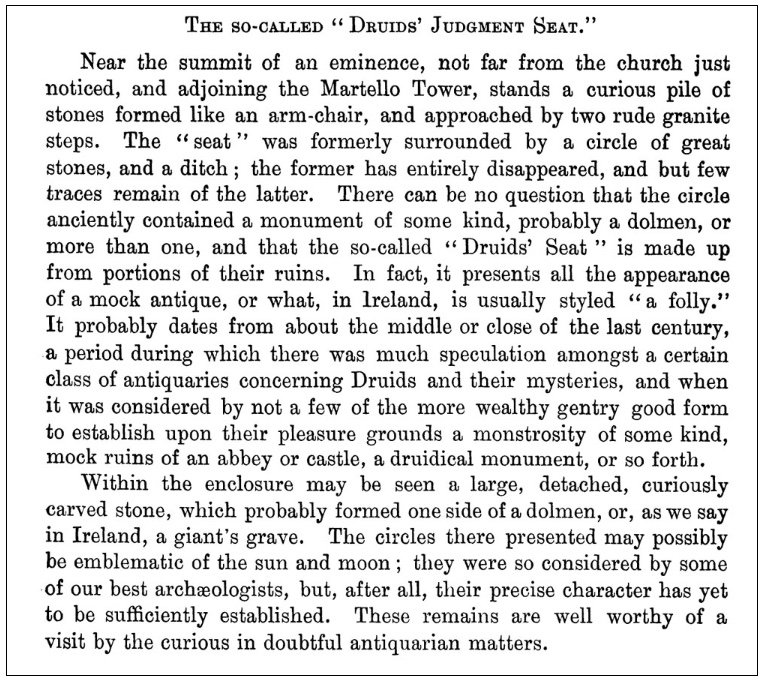

This article – by William Wakeman – appeared in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland December, 1896. It introduces an element of scepticism, which we should perhaps explore. The excellent Killiney History website has collected together a number of writings and observations about this site.

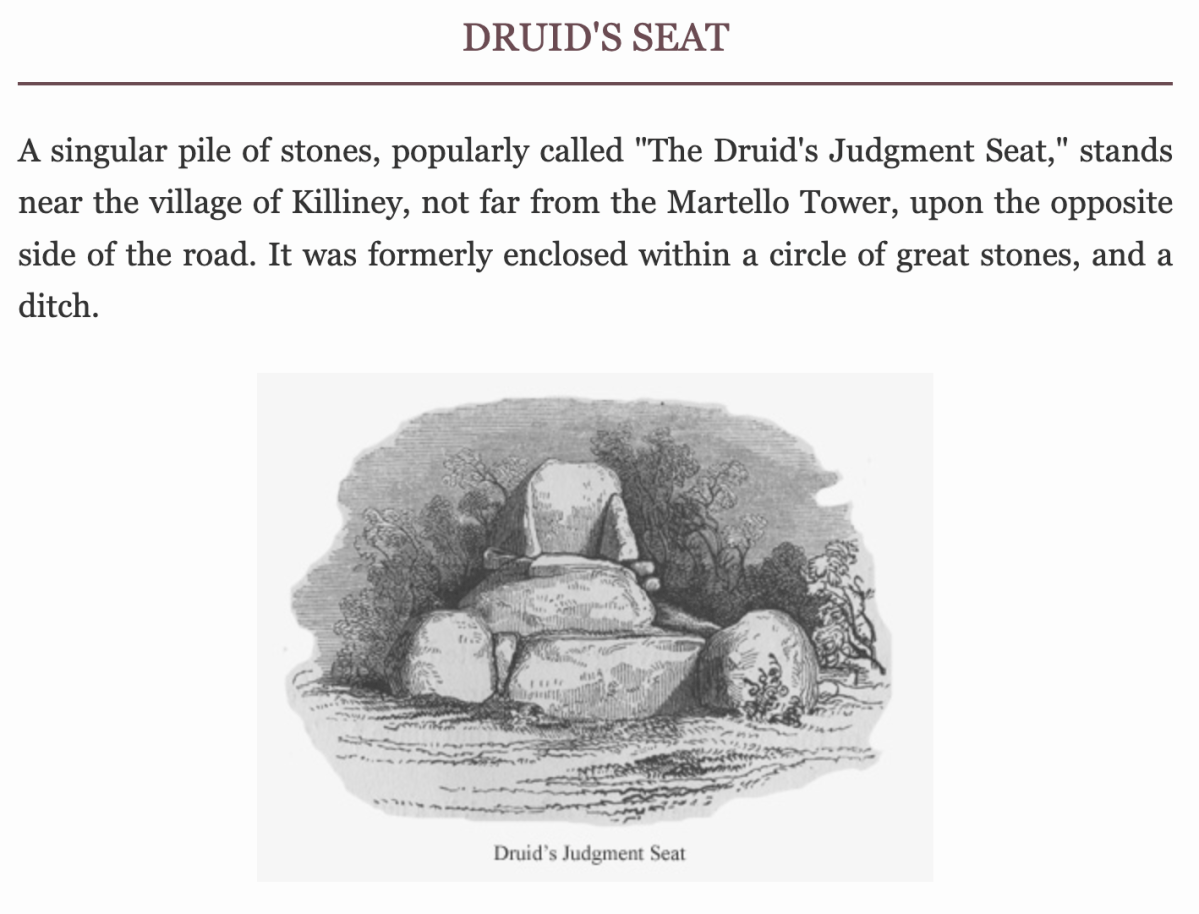

John Dalton writing in 1858 seems quite satisfied of the antiquity of the Judgment Seat. The Gazetteer of Ireland states “A well-preserved Druidical circle with its priests’ seat and its sacrificing stone, occur within a carefully kept enclosure, behind Mount Druid demesne, and near the Martello Tower, but is made accessible by the proprietor to respectable visitors.”

Killineyhistory.ie

William Wakeman, a well known antiquarian of the last century, appears to have been the first to condemn these remains as spurious. “Formerly it was enclosed within a circle of great stones and a ditch. The circle has been destroyed and the ditch so altered that little of its original character remains. The seat is composed of large rough granite blocks and, if really of the period to which tradition refers it, an unusual degree of care must have been exercised for its preservation. The stones bear many indications of their having been at least rearranged at no very distant time. Small wedges have been introduced as props between the greater stones. The right arm is detached from the other part, to which it fits but clumsily. The whole, indeed, bears the appearance of a modern antique, composed of stones which once formed a portion of some ancient monument.”

Killineyhistory.ie

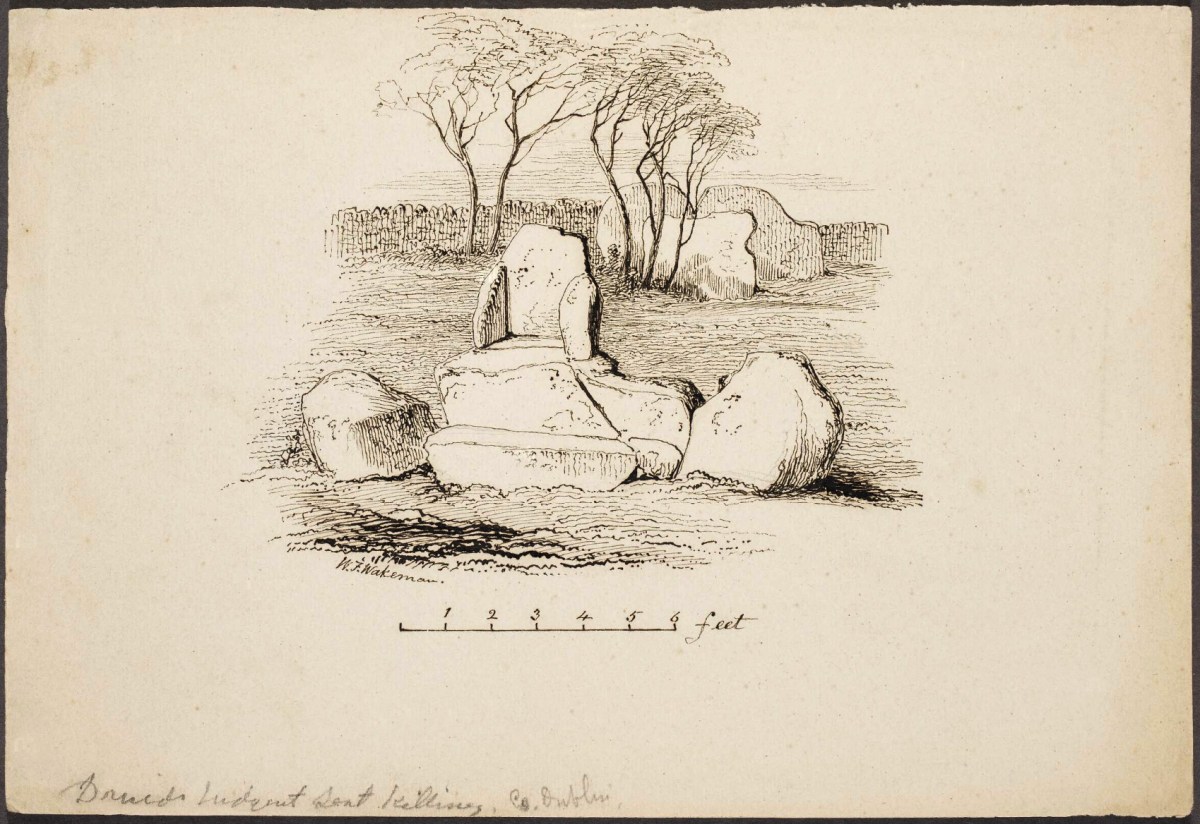

These photographs were taken by William Frazer in 1898. The arrangements of stones at that time are very similar to what we see today – well over a century later – but with far less growth of ground cover.

Above: Druid’s judgement Seat, Killiney – from Library of Ireland archives.

Elrington Ball [1863–1928] confirms this view of the Druid’s Judgment Seat. The stones of which it is composed formed part of a Sepulchral memorial dating from very early times, consisting of three small cromlechs, surrounded by a circle of upright stones about 135 feet in diameter, and, at the time of its first attracting attention, in the 18th Century when everything prehistoric was attributed to the Druids or the Danes, it was assumed to be a Pagan Temple . . . Near the circle was discovered at the same time an ancient burying place, and some stones with curious markings, which are still to be seen. The burying place was of considerable extent, the bodies, which were enclosed in coffins made of flags, having been laid in a number of rows of ten each . . .

Killineyhistory.ie

Finally Woodmartin [Traces of the Elder Faiths of Ireland 1902 Vol 11] makes the sweeping statement: the entire structure leaves the unmistakeable impression of very modern fabrication, and it is a mere clumsy attempt to gull the public . . . As seen to-day these relics of antiquity present rather an unlovely picture, in an obscure and ill-kept corner, surrounded by an unsightly hedge, where weeds and brambles share their ancient sanctity; they seem to arouse but little interest . . .

Killineyhistory.ie

Today, the jury seems to be out on what we are looking at on this site. Time has undoubtedly changed the shape of things: wouldn’t we like to go back a while and see the burying place of considerable extent with all those . . . bodies, which were enclosed in coffins made of flags, having been laid in a number of rows of ten each . . . ? But we do appreciate that a former landowner must have donated the land to excite our interest!

A good tailpiece from William Wakeman