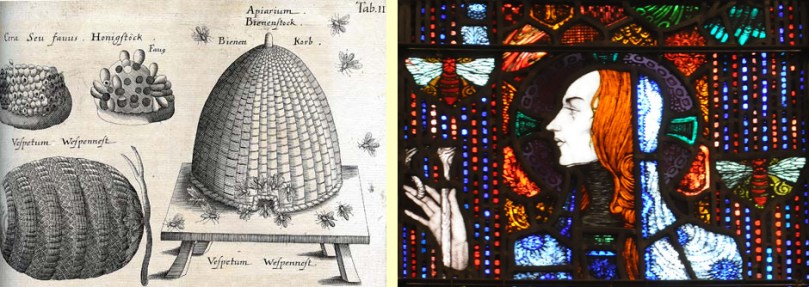

Right: Harry Clarke’s St Gobnait

- With all the excitements of the hurricanes this week bringing down trees and taking out power and telephones, we almost forgot to celebrate Saint Gobnait’s Day.

- Saint who?

- Saint Gobnait – 11th February.

- But what sort of a name is Gobnait?

- It sounds like Gubbnet. Not an unusual girl’s name in Ireland: Finola went to school with one. She seemed happy enough with it.

- But imagine calling a little baby Gobnait… What does it mean, anyway?

- Er, not sure really: there’s a suggestion that it’s similar to Deborah. That means Honey Bee. Also there’s an Irish word Gabhan which means Blacksmith, and our Saint is supposed to be the patron of ironworkers.

- So what’s the story of Saint Gobnait?

- Um, there isn’t one. There’s no history or hagiography about her… But she is mentioned in the ‘Lives’ of St Abban and St Finbarr.

- But no doubt you are going to tell me that there’s lots of folklore about her?

- Exactly! This is Ireland after all. She’s celebrated in Ballyvourney, in the Gaeltacht area of Cork. She’s Cork’s local saint. However, she came from somewhere else – possibly Clare, maybe the Aran Islands. She was visited by an angel who told her to travel until she came upon nine white Deer, and that would be the place for her to settle.

- Did she find the nine white Deer?

- She did. But not until she had met three white Deer – in Clondrohid, and then six white Deer – in Ballymakeera, both in County Cork. But she carried on until she reached Ballyvourney; that’s where she met the nine white Deer and so founded her religious community there. It’s a site of pilgrimage today: there’s a church and a Gobnait’s Well which is dried up now, and which is said to be haunted by a white Stag. There is evidence that the well is still venerated today – rags and ribbons are tied to the trees and offerings are left there. Interestingly, excavations around the site in Ballyvourney revealed evidence of ancient ironworkings.

- So it looks as if Saint Gobnait was superimposed on some pre-Christian traditions?

- Yes, very much like Saint Brigid.

- Anything else which sets her apart?

- Bees! She is always depicted with her Bees: she is supposed to have had great powers of healing and could even cure the plague with a medicine made from honey. Interestingly there are folk traditions that the soul leaves the body in the form of a Bee or a Butterfly. Bees could therefore be incarnations of our ancestors; perhaps that is why it’s important to ‘tell’ the Bees our family history – births, marriages and deaths. There were also once laws called Bech Bretha – Bee Judgments.

- So what am I supposed to do on Saint Gobnait’s Day?

- Think about Bees, ancestors, iron and healing… And do the ‘Rounds’ on Pattern Day. This involves going around the well or church either three times or three times three times, always clockwise. At Ballyvourney the pilgrims also touch the Sheela-na-gig as part of the turas (journey).

- Sheela-na-gig?

- That’s a statue of a female figure with prominent genitalia. There’s one carved on the wall of the church at Ballyvourney, which is supposed to be a representation of the Saint.

- That certainly sounds pagan!

- Possibly something to do with fertility. There are a lot of examples in Ireland and Britain, almost always associated with churches. Perhaps just a medieval joke – or something which has a meaning now lost to us.

- So, is that everything that there is to know about Saint Gobnait?

- No – at Ballyvourney the Parish priest looks after a 13th century carved wooden figure of the Saint, and this is brought out on her day and also on Whit Sunday. Some people supposedly still use a Tomhas Ghobnatan: a length of ribbon or thread which is measured against the carved figure and then used as a healing charm. There are other sites in Ireland dedicated to her: a shrine and well in Dunquin, and Tobar Ghobnait, another well in a ruined oratory at Kilgore on the Dingle Peninsula, County Kerry. Here is found a simple ancient stone bowl which is always full.

- How active is the pilgrimage at Ballyvourney?

- Very active: the church is always crowded on the day, and there are long queues waiting to measure their ribbons against the wooden statue after doing the ‘rounds’.

- Well, thank you: I will take a trip up to Ballyvourney…

- It’s worth going on a Sunday to hear the Mass sung in Irish. Sean O’Riada formed a choir there which is still going strong today, now led by his son Peadar.