As it happens, the posts on the Goat and Skeam Islands, and the others listed last week, were also among my own favourites this year, but I want to concentrate on posts that didn’t get a look-in then. Be warned – some of them tap into my nerdy side.

Readers will know how I love some meaty research, especially if I can combine it with photographs, and I started off the year with a bang with two posts on the Anglo-Normans in West Cork: Hiding in Plain Sight. I had the huge advantage of piggy-backing on the work of Con Manning, esteemed medieval archaeologist, and together we looked at sites that might give us clues at the presence of the Anglo-Normans in this part of the country. This was particularly significant because they have left behind so few clues to their presence – or so it seemed. Turns out we were looking in the wrong places after all. One of the sites we think is an Anglo-Norman Ringwork is at Cnockeens, across from Dunmanus Castle (above), currently labelled a cliff-edge fort in the National Monuments records.

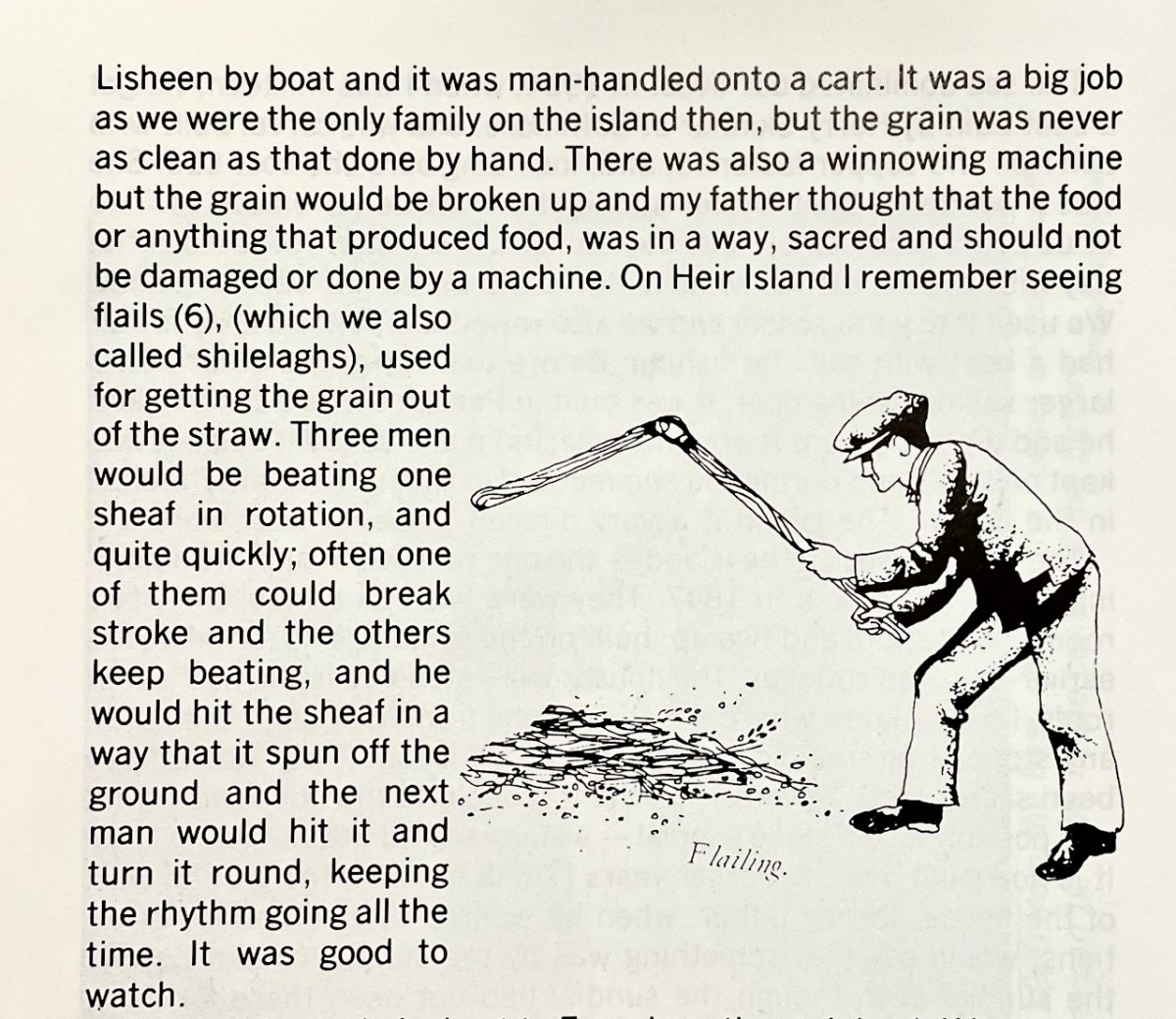

I also loved a three part examination of a book, discovered in Inanna Rare Books, about the voyage of St Brendan. What made this book special was that it contains a facsimile reproduction of a 14th century illustrated manuscript which takes us through the Navigatio, incident by incident, with subtitles in Gothic-script Latin and ‘joyful’ pen-and-ink drawings.

A highlight for me this year was my visit to Owen Kelly, Stitching and Storytelling Among the Rocky Fields. To hear Owen talking about his practise, his inspirations, his methods and his stories, is to spend time with a master craftsman – it’s humbling and elevating all at once. The mermaid in the lead photograph is his work, as is the cheerful fellow below.

I did a ‘co-op’ blog with Amanda Clarke of Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry. We went to the end of the world – well, the far reaches of Kerry, to look for a sacred site that hadn’t after all, as she was afraid it might have, dropped off the cliff. This was a journey into the realm of Punishment and Pilgrimage in 16th Century Ireland and I don’t think I will ever forget Amanda’s excitement at what we found.

Also with Amanda, we had a day on Sherkin Island in May, and as these things tend to do, it turned into a three part blog exploring the Island, the Castle and the Friary. Despite having been on Sherkin many times, I had never managed to get inside the Friary before, but this time we found an open gate (shhh) and had a good old explore. The feature photo at the top of the post was taken by Amanda that day – coffee break on Sherkin.

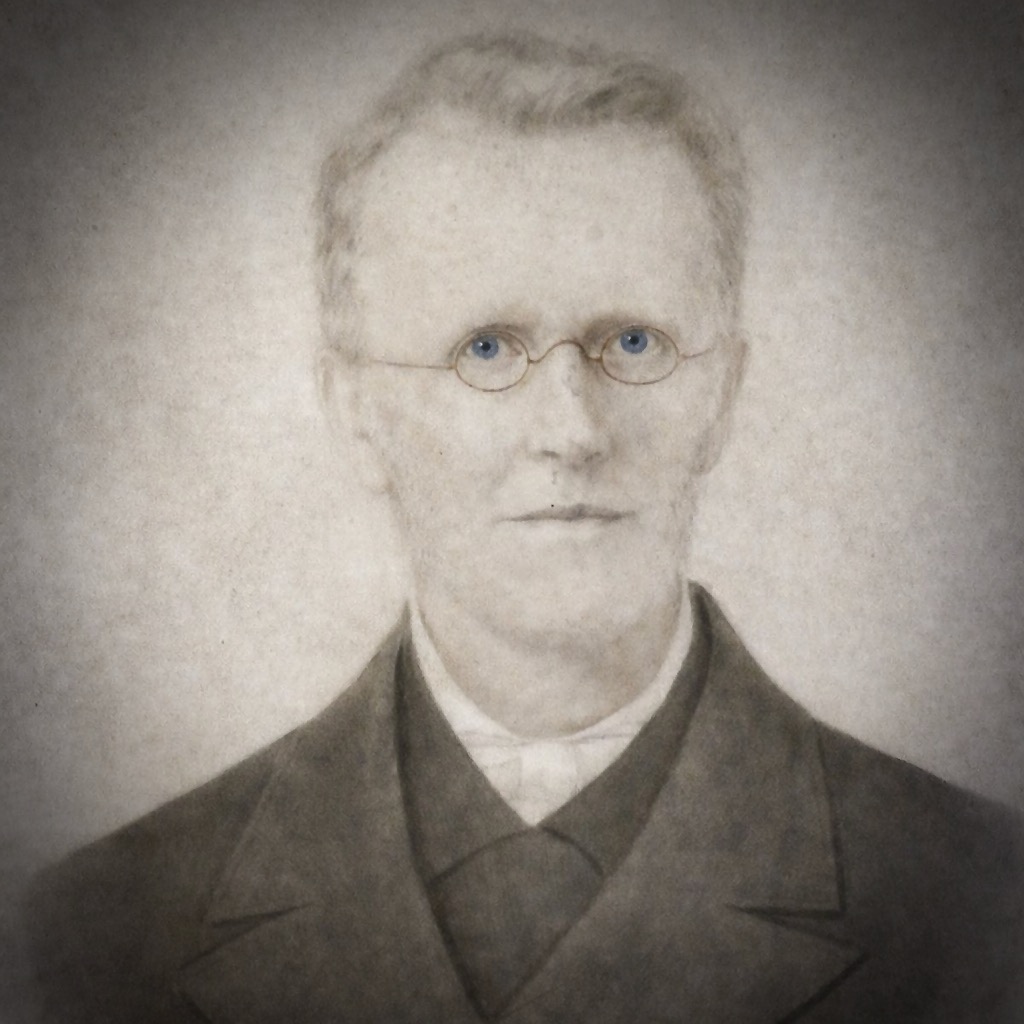

And – although it wasn’t my blog post, I really enjoyed being on the podcast Cork Chronicles with Shannon Forde. We drove out to Toormore and talked about Rev Fisher, the protagonist of my Saints and Soupers series, and the firestorm of accusations and counter-accusations about his actions during the Famine. You can listen to the podcast by clicking on the image below.

I am thankful to Rev Terry Mitchell who facilitated my access to the vestry so that I could photograph this original portrait of Rev Fisher. Isn’t it wonderful? It’s probably an albumen print , dating to the 1860s or so. It’s been hand-coloured and although most of the colour has faded, the gold-rimmed spectacles remain as well as those startling blue eyes.

And on we go to 2026! This will be the 15th year for the blog – our first post was in Oct 2012 and garnered 5 views. Just an advance notice that operations may slow for January as I am moving house. Details to follow as sorting and packing allows. Don’t worry, I am staying in West Cork, not far from where I am now. But I sure will miss this view!

Happy New Year to all my wonderful readers – you are why I do this.