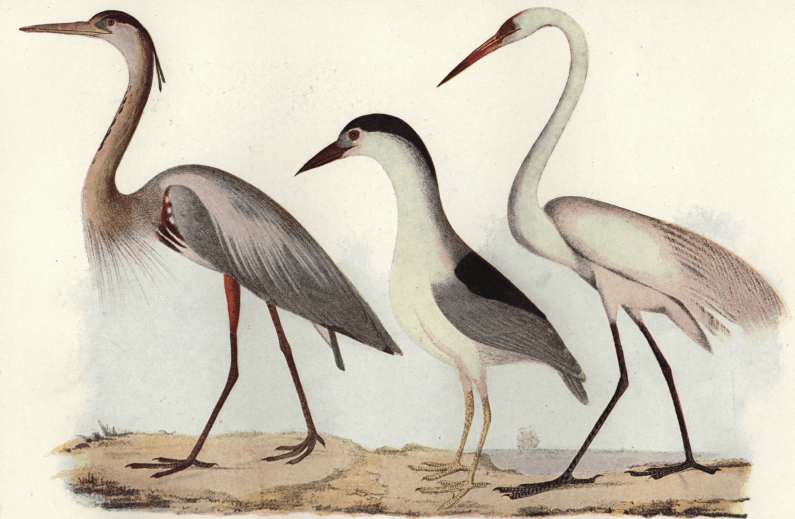

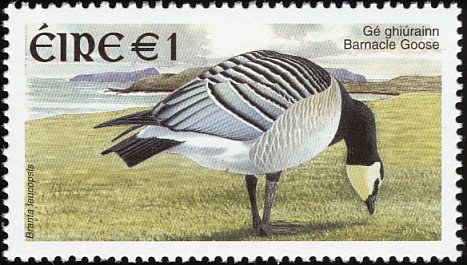

Here at Nead an Iolair we are on a flight-path. Not for Eagles – which you might expect (Nead an Iolair means Nest of the Eagle) – but for Herons. I have often watched one of these most prehistoric seeming of birds lazily flapping its way across our view, apparently from the hills behind us, towards the islands in front – no doubt heading for its shallow water fishing grounds. Yesterday I saw the Heron being mobbed persistently by Crows – presumably worried about their eggs and young – but our Old Nog ignored the harrying and continued stolidly on his way. Herons roost in trees – and do so communally: I would like to search out the Heronry, which would be a rich experience in both sound and smell.

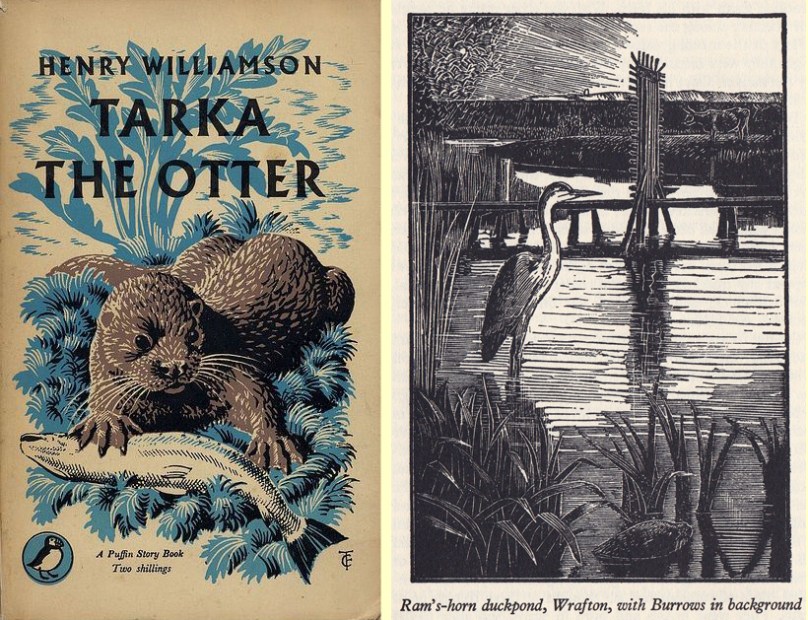

Old Nog – there’s a good name for this character. It comes from Tarka the Otter, probably the most famous book by Henry Williamson – a master nature writer and novelist who lived from 1895 to 1977, spending many of those years in Devon. The book – winner of the Hawthornden Prize for Literature in 1928, and never out of print since it was published – opens with these lines:

…Twilight upon meadow and water, the eve-star shining above the hill, and Old Nog the heron crying kra-a-ark! as his slow dark wings carried him down the estuary. A whiteness drifting above the sere reeds of the riverside, for the owl had flown from under the middle arch of the stone bridge that once carried the canal across the river…

The story of Tarka unfolds in places I know well: I was in Devon for nearly four decades before I came here to Ireland. The stone bridge that once carried the canal across the river is still there, not far from where I once lived: the old aqueduct on the Rolle Canal over the Torridge now carries the driveway to a private house. Tarka’s travels took him right up to the heart of Dartmoor: to Cranmere Pool, close by which stand, today, the ruins of an old farm. This was once described (by William Crossing the Dartnoor writer) as ‘the remotest house in England’. My mother’s grandmother was born and raised there in the nineteenth century, one of fourteen children from a single generation. The name Cranmere comes from ‘mere of the Crane’, and the Crane was and still is a name often given, in England and Ireland, to the Heron.

Having established, perhaps somewhat tenuously, my own relationship to the Heron, I will enlarge upon the bird’s place in folklore and tradition. The Heron was once a regular dish on the English medieval banqueting table: as the property of the crown, heavy fines were levied on anyone caught poaching the bird, while in Scotland the penalty was amputation of the right hand. From observations of the bird standing still for hours in shallow water waiting patiently for its lunch to pass within range of its sharp bill, anglers assumed that the Heron’s feet had some means of attracting the fish towards it, and it was once a custom for the fisherman to carry a Heron’s foot for luck, but also to coat the fishing line with Heron’s fat and a noxious mixture made from boiled Heron’s claws.

Aesop penned a fable about the Heron and the Fox: Fox invites the Heron to dinner but only provides a shallow plate of soup which the bird is unable to partake of because of its long beak. In retaliation, Heron invites Fox, and provides the food in a bottle with a long narrow neck: Fox is unable to share in this food. The moral? ‘One bad turn deserves another’.

I have never successfully photographed a Heron, but you can see some excellent pictures in the portfolio of Sheena Jolley – a professional wildlife photographer who lives not far away from here, in Schull. And here’s another – by our friend Lisa who lives out on the Sheeps Head.

In Ireland the Heron is known as Corr reisc or Corr-ghrian (crying Crane). Although a common bird, I have found no specifically Irish folktale which includes Herons: if you know of one I would be delighted to hear it. There are some superstitions: if a Heron lands on your house you will have good luck, and if some of its plumage floats down to you – then you will have amazing luck! So, come on Old Nog – how about an occasional perch on the roof of Nead an Iolair? And, while you’re at it, throw out a few feathers as well… Of course, if there are more than one of you we will be able to say …there goes a siege of Herons…!