Finally getting back to good old St Brendan and his voyage. (You can catch up on Part 1 and Part 2 if you haven’t read them already.) While writing this post I have been listening to one of my all time favourite pieces of music – The Brendan Voyage by Sean Davey, with the great Liam O’Flynn on the uillinn pipes. Robert wrote about the thrilling experience we had at the National Concert Hall where we attended a memorial concert for Liam O’Flynn which featured the whole Brendan Voyage, with Mark Redmond on the pipes. That post, Piper to the End, has several links to extracts from the Brendan voyage, but I will just post one movement here, and because I am half Canadian it has to be the Newfoundland Suite. Turn the volume up.

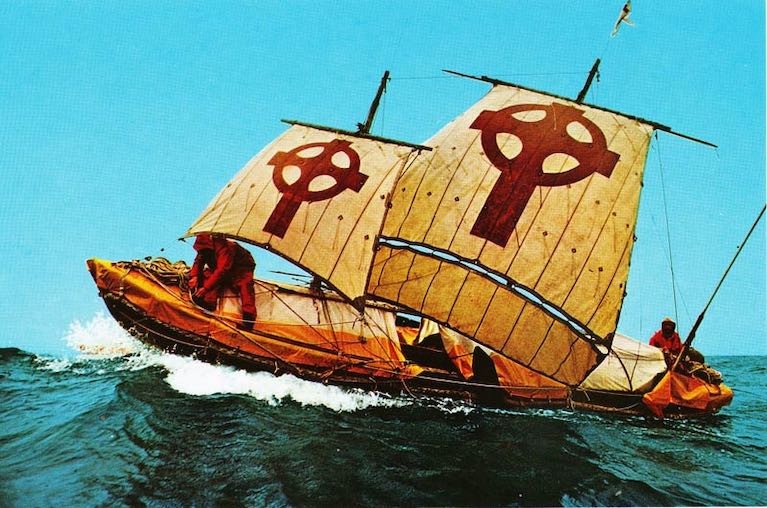

This music was written to celebrate the extraordinary journey taken by the late Tim Severin, tracing St Brendan’s voyage across the Atlantic. You can read the book (it’s a great read) or watch the documentary – I found part 1 and Part 2 online. Tim was an incredible explorer – the Brendan Voyage was one of many epic adventures he undertook to trace the footsteps of early voyageurs and travellers – you can read much more about him at his website, from which this photo, and the lead photo above, was taken, with thanks.

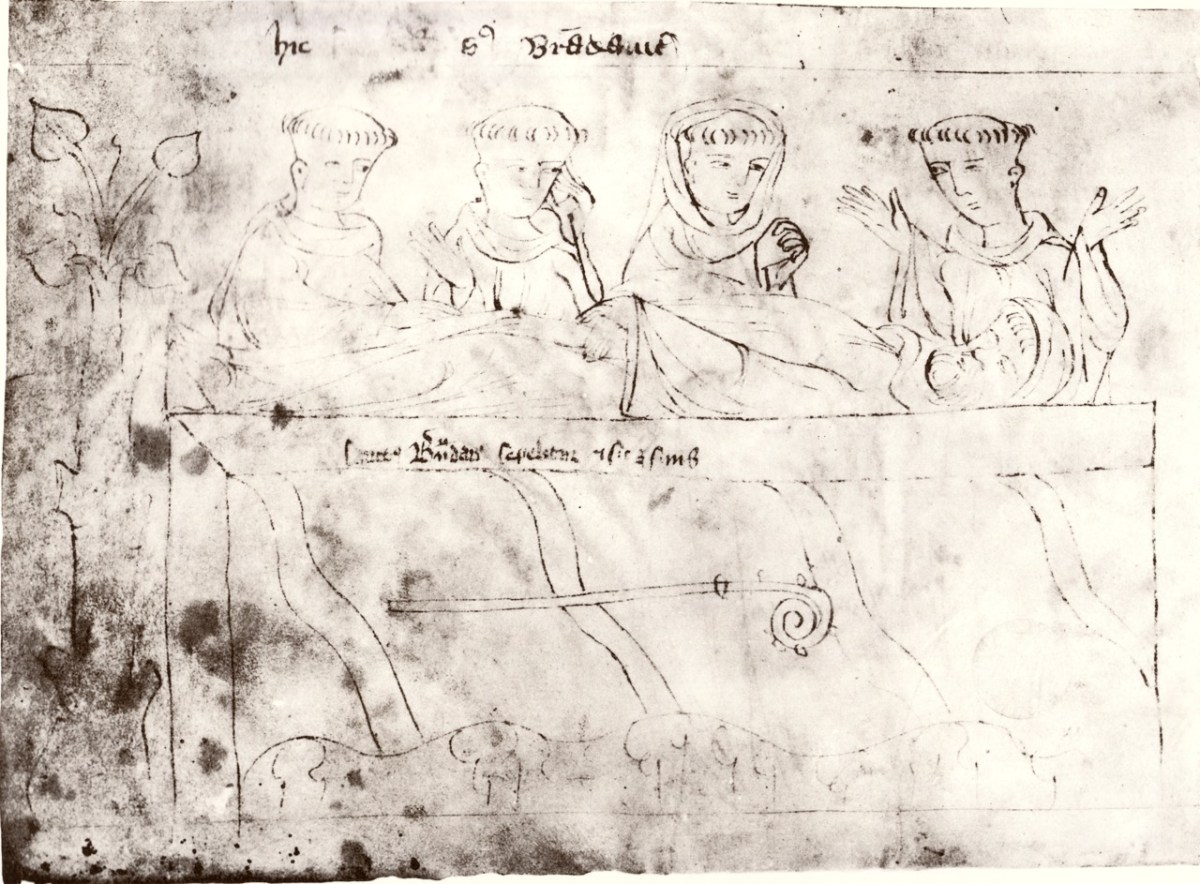

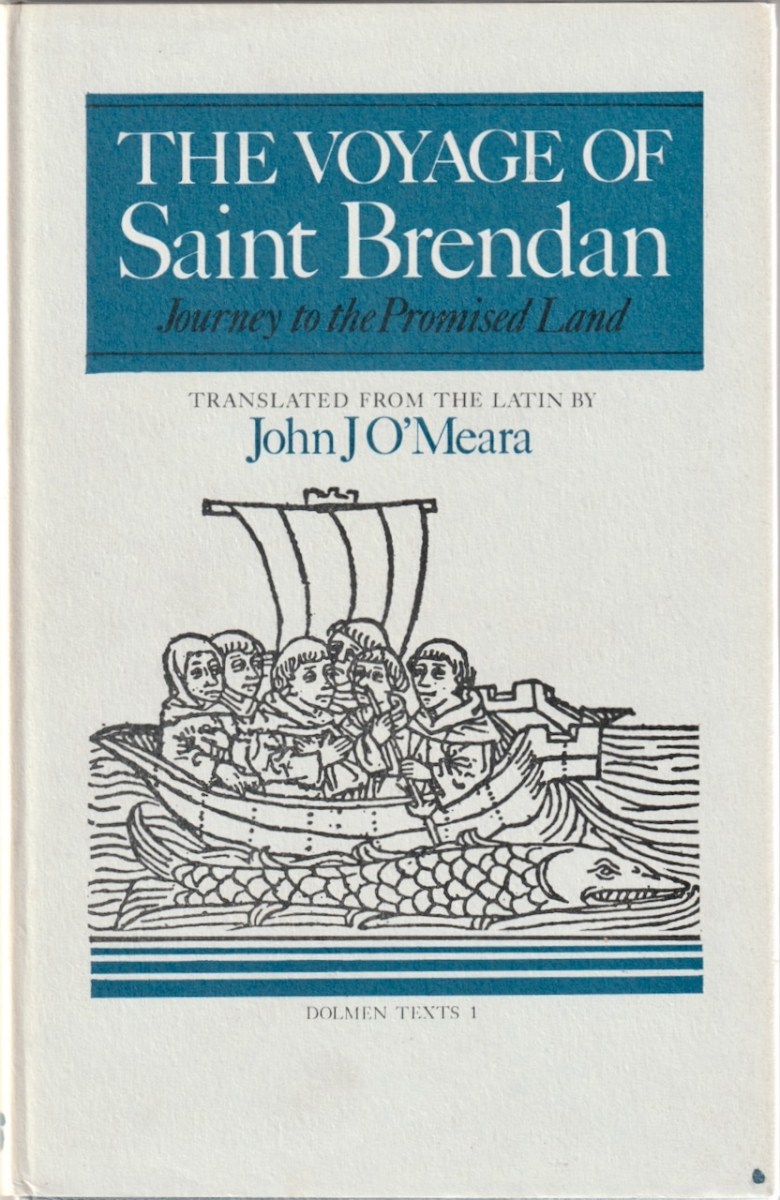

OK – back to S Brandanus and the 1360 graphic novel that illustrated his adventures for a medieval audience. For my final series of images from the book, I am using the translation this time of the great Irish scholar, John J O’Meara. In 1976 he translated the Navigatio into English, published by the Dolmen Press. He explains in his Introduction:

. . .within a hundred years of his death there already existed a primitive account in Latin of Brendan’s quest for that happy land [the Land of Promise]. This account was ecclesiastical in general character, but influenced the creation of the secular, heroic Voyage of Bran, written in Irish, which goes back to the late 600’s or early 700’s.The Latin Voyage of St Brendan, which is here translated, was written in Ireland perhaps as early as 800.

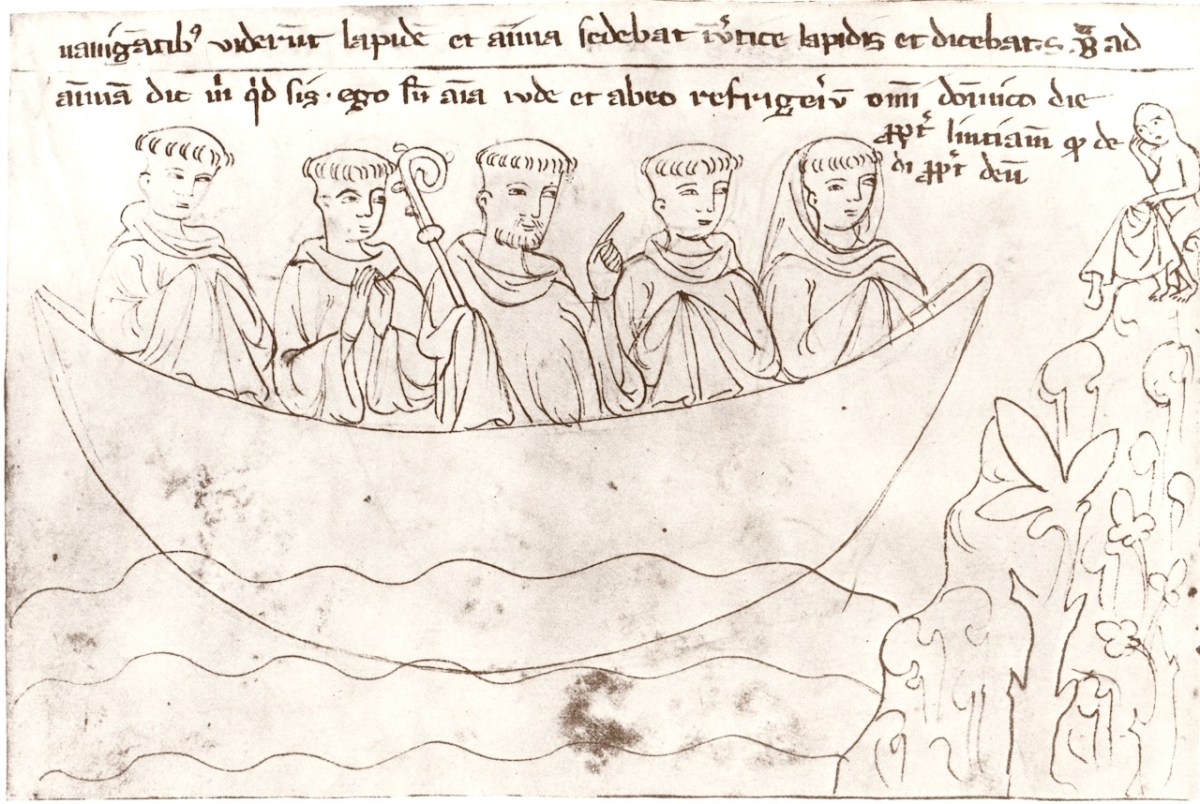

O’Meara illustrated his book with woodcuts from Sankt Brandans Seefahrt, printed by Anton Sorg at Augsburg in 1476. As you can see, they are different in character from our manuscript, being woodcuts for one thing, rather than pen and ink drawings. For example, the illustration on the cover is of the famous incident with the whale, covered in Part 2 of this series, while the illustration below is of the Unhappy Judas on a rock in the sea. Contrast it with the same scene from S Brandanus, below the first quote.

Nevertheless, O’Meara’s translation and the S Brandanus illustrations correspond perfectly, indicating that both were based on the same text. I am using the story of Brendan’s meeting with the Unhappy Judas. Regular readers will remember that I wrote about this once before, in my post Harry Clarke, Brendan, Judas – and Matthew Arnold. While the stories are the same, Arnold’s poem ends with Judas disappearing, while the story from the Voyage carries on. Here goes.

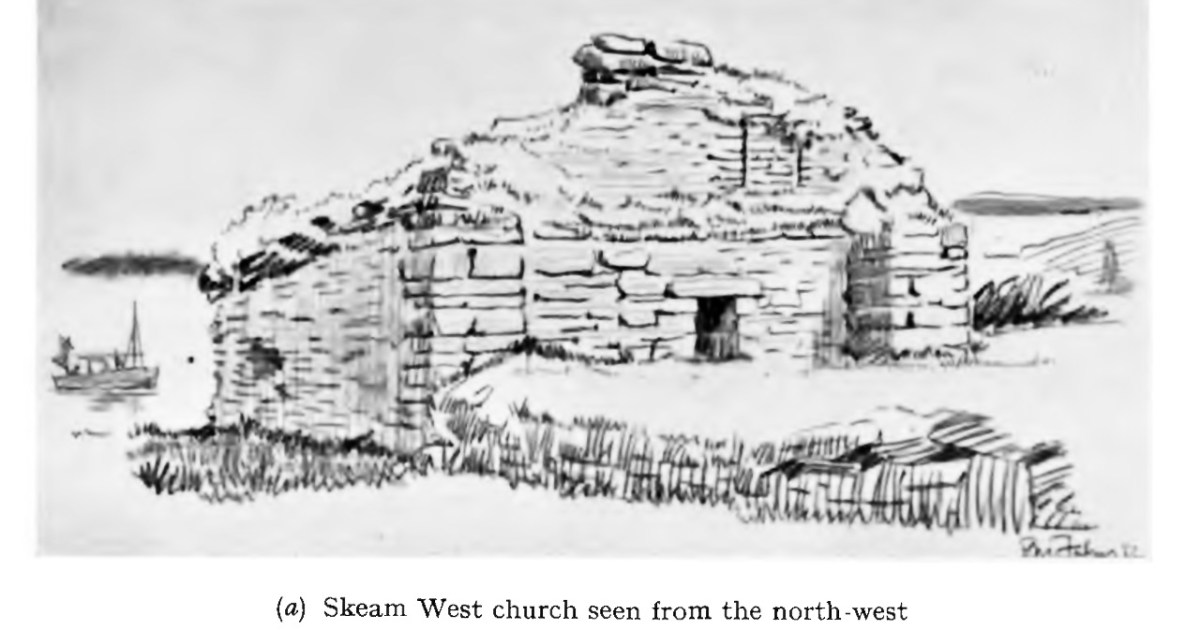

When Saint Brendan had sailed towards the south for seven days, there appeared to them in the sea the outline as it were of a man sitting on a rock with a cloth suspended between two small fork-shaped supports about a cloak’s lengths in front of him. The object was being tossed about by the waves just like a little boat in a whirlwind. Some of the brothers said it was a bird, others a boat. . .

Blessed Brendan questioned him as to who he was, or for what fault he was sent here, or what he deserved to justify the imposition of such penance?

The man replied: “I am unhappy Judas, the most evil trader ever. I am not here in accordance with my desert but because of the ineffable mercy of Jesus Christ. This place is not reckoned as punishment but as an indulgence of the Saviour in honour of the Lord’s resurrection.. . .

When I am sitting here I feel as if I were in a paradise of delights in contrast with my fear of the torments that lie before me this evening. For I burn, like a lump of molten lead in a pot, day and night, in the centre of the mountain that you have seen. . . .

But here I have a place of refreshment every Sunday from evening to evening, after Christmas until the epiphany, at Easter until Pentecost, and on the feast of the purification and assumption of the Mother of God. After and before these feasts I am tortured in the depths of hell with Herod and Pilate and Annas and Caiphas. And so I beseech you through the Saviour of the world to be good enough to intercede with the Lord Jesus Christ that I be allowed to remain here until sunrise tomorrow, so that the demons may not torture me on your coming and bring me to the fate I have purchased with such an evil bargain.

Saint Brendan said to him, May the Lord’s will be done! Tonight until the morning you will not be eaten by the Demons.

The man of God questioned him again saying what is the meaning of this cloth?

The other replied I gave this cloth to a leper when I was procurator for the Lord. But it was not mine to give. It belonged to the Lord and the Brothers. And so it gives me no relief but rather it does me hurt. Likewise the iron forks on which it hangs I gave to the priests of the temple to hold up cooking pots. With the rock on which I sit I filled a trench in the public road to support the feet of those passing by, before I was a disciple of the Lord.

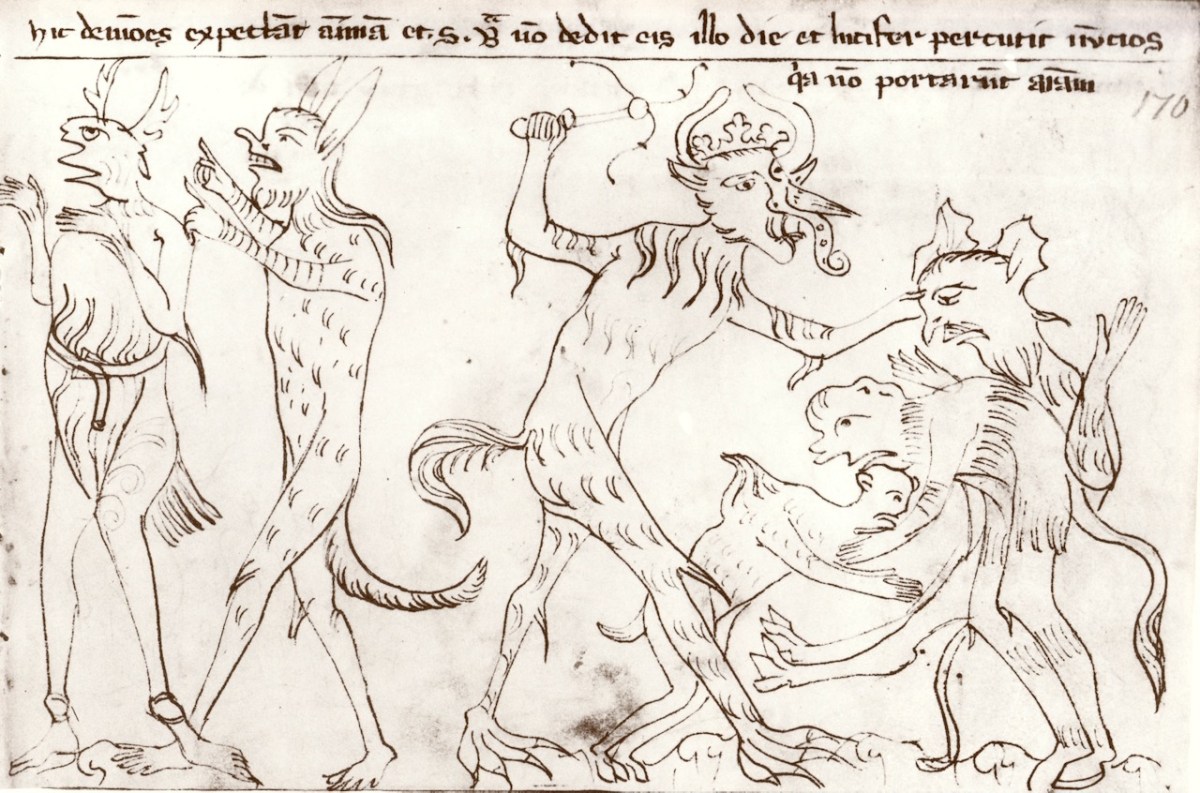

The story continues, with the demons coming to take Judas back to hell, upon which Brendan forbids them to do so. The following morning, when they come to fetch Judas,

. . . an infinite number of Demons was seen to cover the face of the ocean emitting dire sounds and saying ‘Man of God, we curse your coming as well as your going, since our chief whipped us last night with terrible scourges because we did not bring to him that accursed prisoner.

They tell him that Judas will suffer double punishment for the next six days because of this, but this also Brendan forbids, in the name of God, saying:

I am his servant and whatever I order, I order in his name. My service lies in those matters which he has assigned to me.

The Demons followed him until Judas could no longer be seen. They then returned and lifted up the unhappy soul among them with great force and howling.

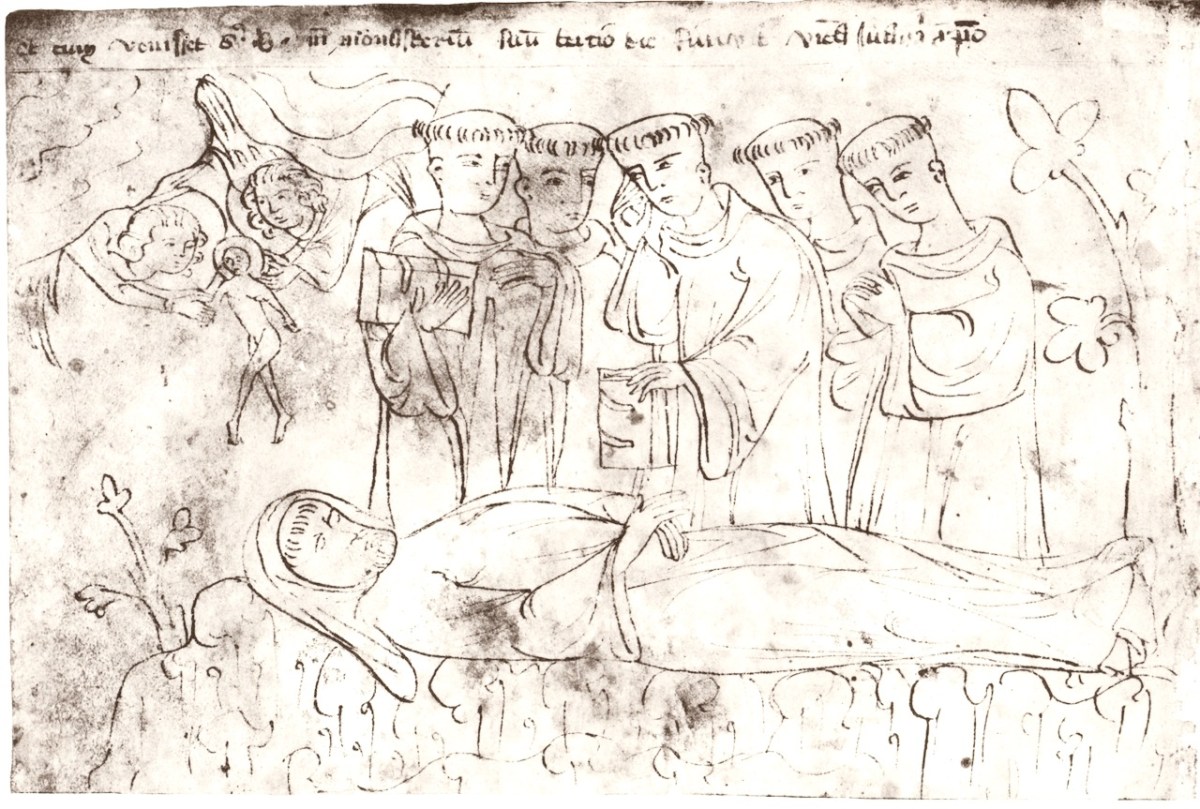

Eventually the voyage ends and Brendan returned home, relating everything that had happened on the voyage and saying that his own time had now come to an end. His dying and death are given less than half a page – an unseemly short few words to bring the voyage to a close.

For when he had made all arrangements for after his death, and a short time had intervened, fortified by the divine sacraments, he migrated from among the hands of his disciples in glory to the Lord, to whom is honour and glory from generation to generation. Amen. End.