At the very far reaches of the Mizen, surrounded by townlands whose names all translate as variants on the theme of rocky fields, in a place with immense views, lies an oasis of creativity and charm: the home of Owen and Kate Kelly and their family.

Three of us, Artist Christina, Blogger Finola, and Writer/Actor/Director Karen, fetched up there on a blue sky day this week, to visit Owen and see his craft. Owen is a stitcher, an embroiderer, a needleworker. He’s also a professional coach (international table tennis), a gardener and a conservationist. Nowadays, he, as a fifth-generation stitcher, makes his living crafting unique garments and decorative elements for high-end clothing.

It has all grown organically from his social media accounts on Facebook and Instagram and Bluesky. Somehow, the like-minded find each other and the army of admirers grows, and the orders start to arrive.

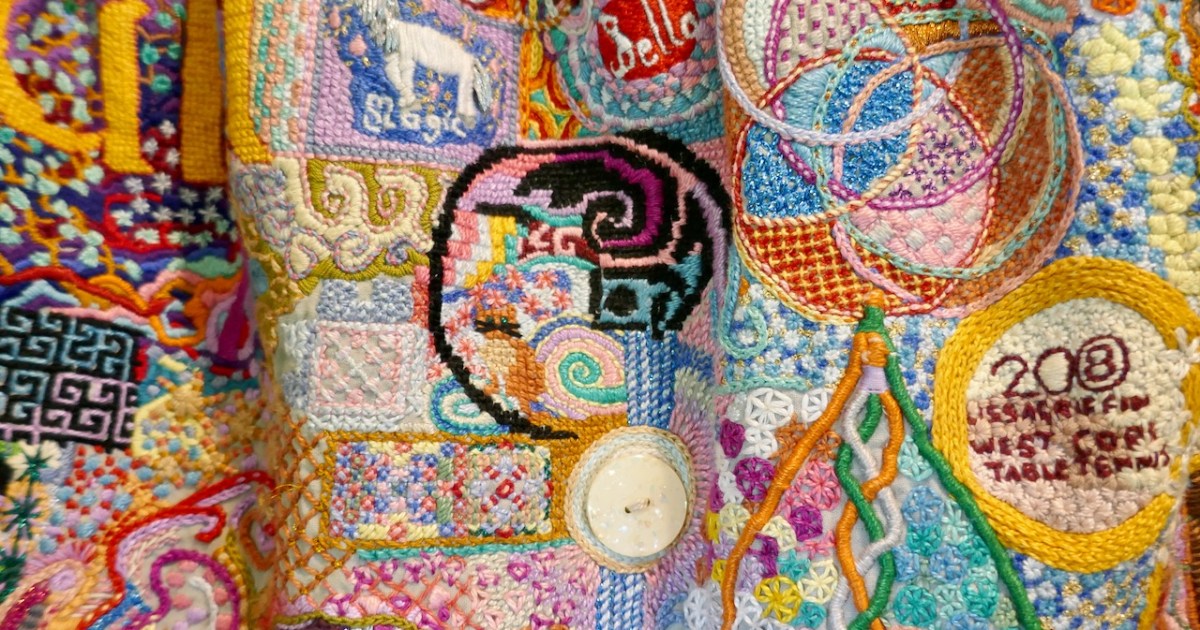

Owen doesn’t just decorate – he tells stories with every piece. The first thing he showed us was his memory skirt, full of his own history. That’s his trip to Glastonbury, here’s a particularly memorable table tennis tournament, the birth of a daughter, his grandmother’s favourite stitch in her favourite colour.

He thinks it’s finished and I certainly didn’t see any place to add more, but heck, you never know.

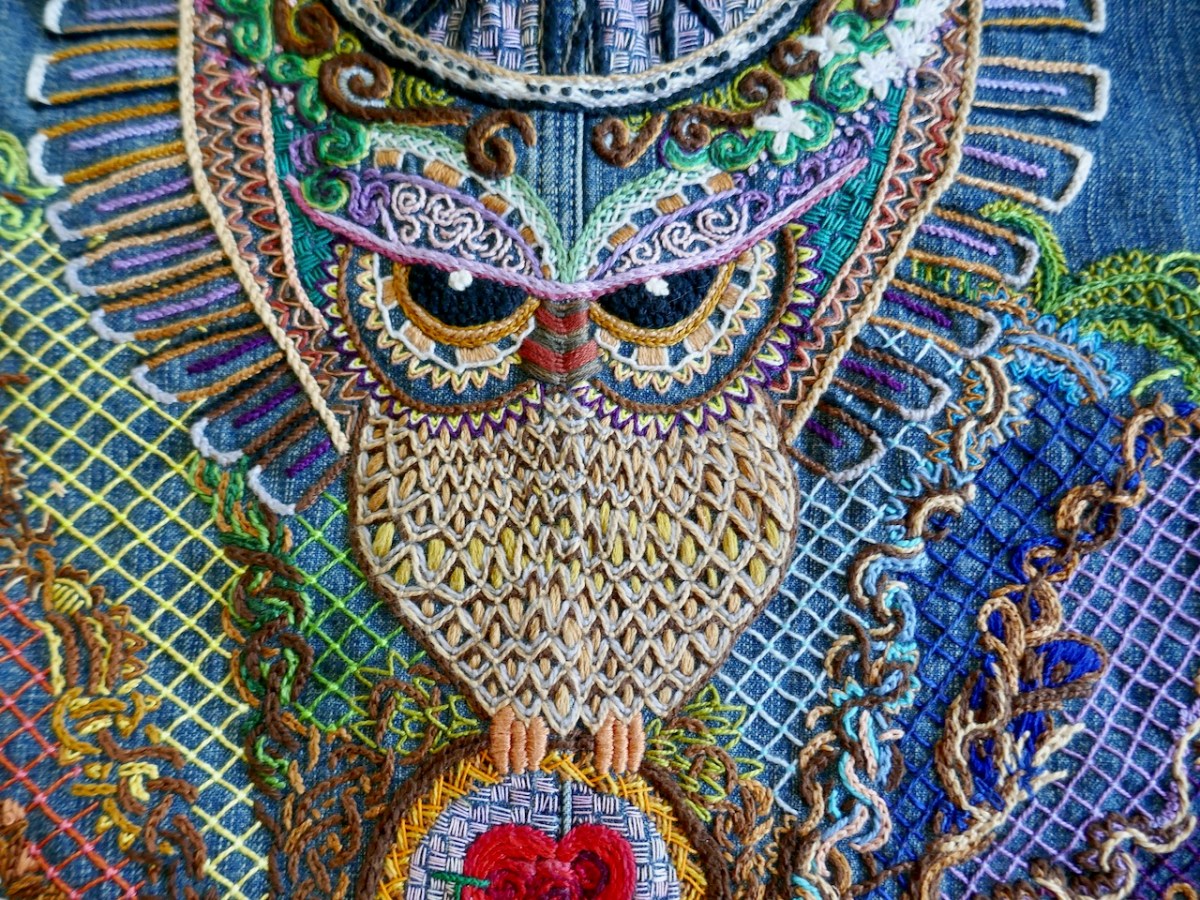

Here’s the back of a jacket that I assumed was an owl – but Owen was referencing the need for masking that so many people feel. That is, they cope with life by concealing their mental struggles, their ADHD or Autistic tendencies, in order to fit in. It’s exhausting, and his depiction is an act of masking in itself, since I jumped to the conclusion that this was a bird.

And the mask is a good piece to take a closer look at the sheer variety of individual stitching styles. I have a vague memory from school of learning blanket stitch, daisy chain, French something-or-other, but Owen must know hundreds of different stitch types. Zoom in!

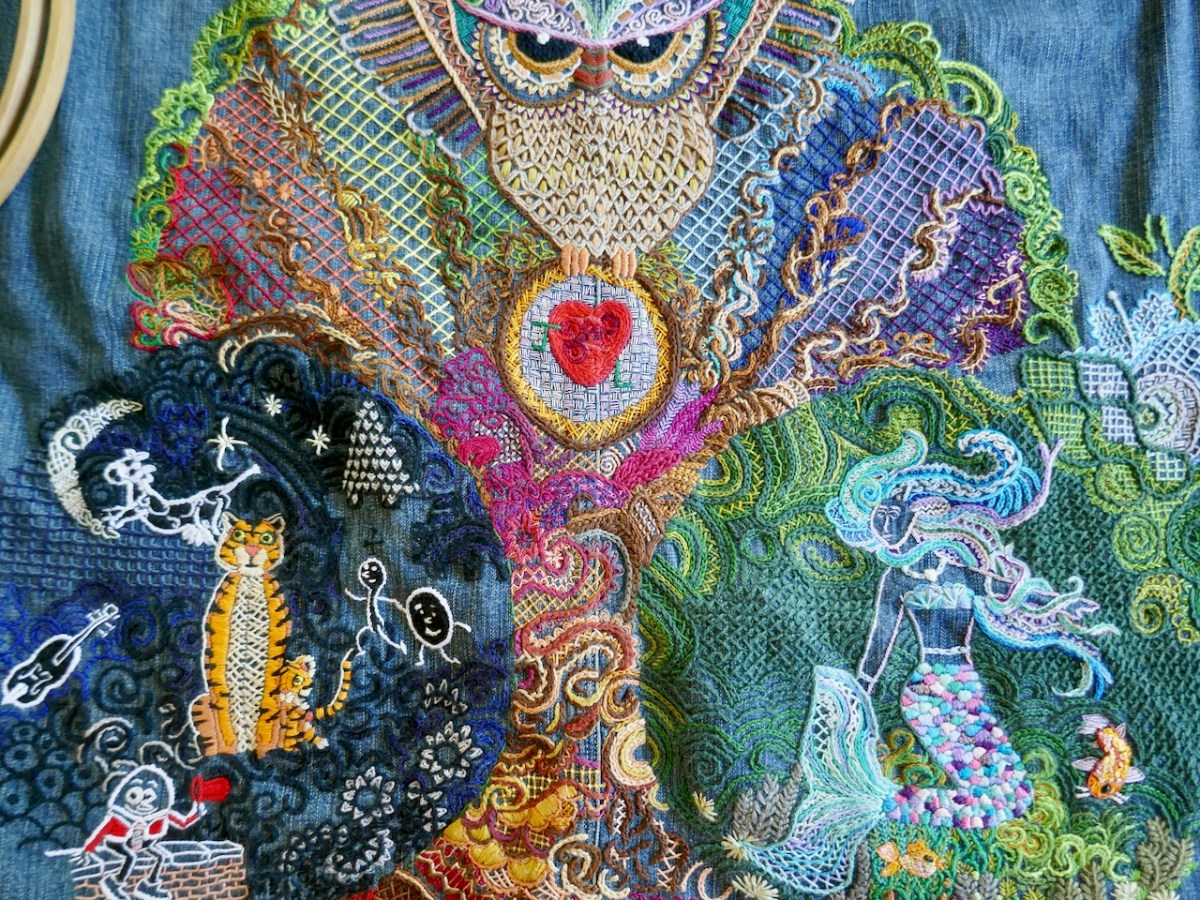

Owen walked us through the process of designing the back of a Ralph Lauren shirt for a client – sorry, that should be, for a friend. That’s what they all turn into. In this case he has already done pieces for other members of the family so he knows the children, the grandchildren, the stories, the likes, the hobbies, the icons they gravitate to.

What fascinated me most is that he doesn’t start out (as left-brained me would do) with a plan – there is no sketch design, no chalk marks on fabric, no story board or end-goal. But in his head is the story he wants to tell. He calls this process ‘flow stitching.’

In this case the story is about a proud grandpa, so there’a grandfather clock and an owl for wisdom, and the heart that he and Grandma once carved on a tree. There’s a tree too, and a rainbow. And, can you see it? The overall shape is a Buddha.

The grandson is there, with the tiger, and the cow jumping over the moon and Humpty Dumpty waving Owen’s signature red hat. The granddaughter loves mermaids. And in between there are all kinds of little symbols and references, in all kinds of different stitches and colours. As I poured over it, all I could think of was – be still my heart – how I would love to be at the unveiling of this wonderful garment.

He learned his skills from his mother and grandmother and of course he got bullied in school but he persisted anyway. He’s heavily influenced by indigenous art, by Indian and Persian designs and by Celtic interlacing and illuminated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells.

He cites his remote location on the edge of the Atlantic as another influence – the colours, the wildness, tuning in to the natural world and the deep tradition of story telling and mythology.

Ongoing projects include his hoops – 6” rounds, each one telling a story, and his quilt pieces, which will (may?) eventually make up a whole quilt. He loves to play with symmetry – with half- or quarter-designs for example, that need to be matched with other halves or quarters to make a whole.

And of course – there’s Seamus! Seamus O’Comanssy is a little stitched guy who is travelling the world. He’s currently in Australia, but before that it was Slovakia and before that France. You can follow his journey – even volunteer to host him!

I’ll leave you with images of a hat – Owen is a hat man and his signature is a red hat. In fact when I met him recently he was wearing a red jacket, a red hat, and an amazing embroidered tie.

And I didn’t leave empty handed – I took away one of Kate’s lovely mugs. She’s been experimenting with a new green glaze and it’s gorgeous. I can report that coffee tastes really good from it too. That’s Kate’s own photograph, below. Her pottery is for sale at the Mizen Visitor’s Centre.

Thanks for such a lovely visit, Owen and Kate.

If you’d like to hear Owen talking about his life and work, tune in to the Stitchery Stories Podcast.