As a retired couple we often get asked what we find to do all day. How do you spend your time? Perhaps there’s a subtle sub-text of ‘way out there in the wilds of West Cork.’ Well, it’s only half way through the month and we have had numerous experiences already in June, including many that revolve around art and music so I thought I would highlight them in this post to give you a flavour of the Wilds.

Robert has written extensively about the thriving art scene established first by the artists and hippies that made West Cork their home starting in the 60’s, a legacy that is celebrated in the Ballydehob Arts Museum. But it’s as true now as it was then and just in our small villages of Schull and Ballydehob we have been to several exhibitions over the last couple of weeks. I am always drawn to photography and I was bowled over in particular by three exhibitions.

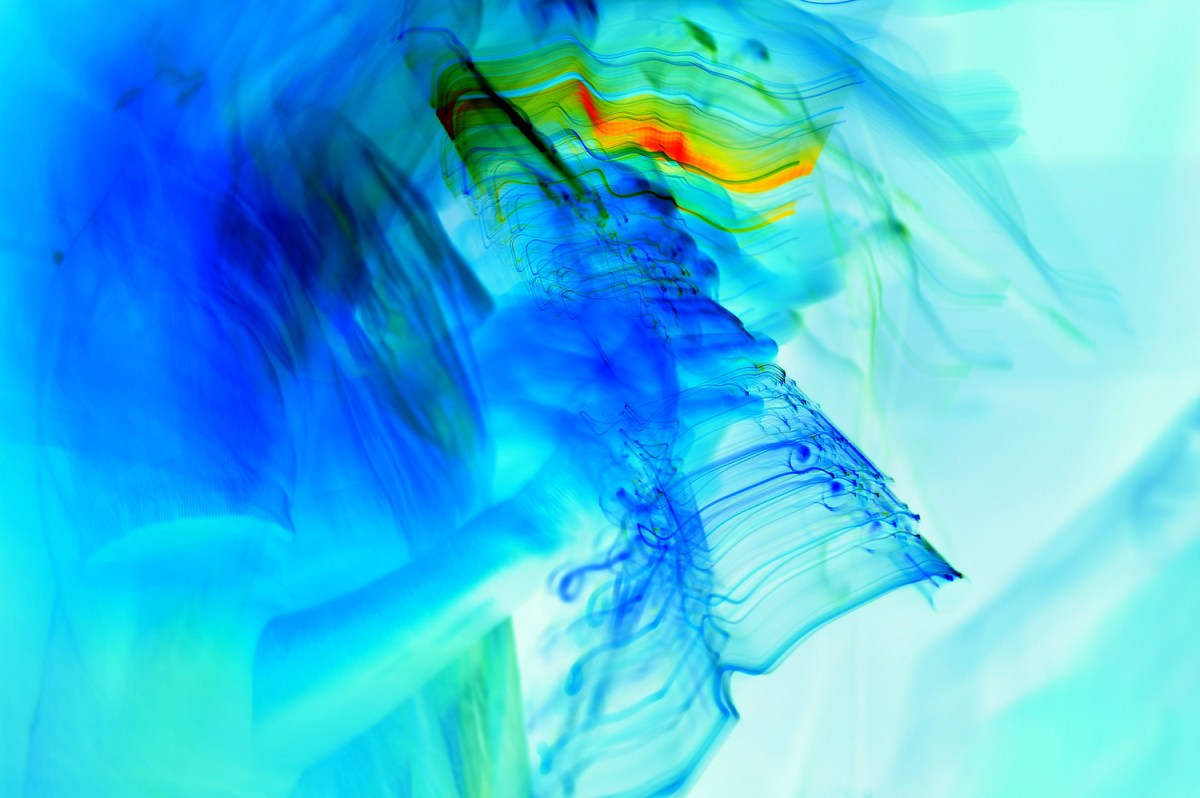

Oliver Nares is exhibiting at the moment in the Working Artists Studio in Ballydehob. The first three photographs in this post are his. The first two are Flutes and the one above is Tambourine. Oliver captures his images live and, as Pól Ó’Cólmán astutely noted at the opening, he photographs the music, not the musicians. Unbelievably, this is Oliver’s first ever exhibition – if the reaction is anything to go by, it won’t be his last!

Another exhibition that left me breathless was Richard Breathnach’s The Bog in the Bale at the Blue House Gallery. Everyone who comes to see this has the same reaction – what is this? An Oil Painting? An abstract? Richard’s photography, which included many many hours of lying in a bog waiting for just the right image, captures the reflections of a bog in those ubiquitous black plastic silage bales – the results are extraordinary and you can see more on his website.

Meanwhile, the Aisling Gallery, situated over Rosie’s Pub in Ballydehob, has an exhibition focused on All Things Maritime. Chris O’Dell’s iconic image of Cobh (above), taken from the sea, is only one of several of his photographs, and the photographs of others, on display in this show. Chris is a distinguished cinematographer who has worked in television and cinema and is now recording his archive.

We went to Kenmare to see the new Butter Market Gallery, recently opened. (OK – that’s in Kerry, not West Cork, but sure it’s only the next parish over.) With a Modern Irish Sculpture show as its premier event, we weren’t disappointed!

One of the standout artists in the Kenmare show for us was Ayelet Lalor – that’s her large piece above destined now for a hotel. Back in West Cork we were delighted that the Blue House Gallery in Schull devoted prime space in their latest show to her work. Titled A Life at Odds, Ayelet uses her iconic female heads to explore her own heritage and influences with an eclectic conglomeration of media including concrete, ceramics, cutlery, garden forks and industrial brooms! The results are both captivating and provocative.

On to the music – our regular Friday sessions have resumed in Ballydehob after two years. It’s always great fun for Robert to participate in these and even more so now as they are earlier in the evening (starting at 7 rather than at 9) so he’s full of beans as he heads off with his melodeon and concertina. His post last week had a clip of them all playing. The Fastnet Maritime and Folk Festival is on here at the moment, so the village is full of musicians, including Jackie Daly and Matt Cranitch, about whom Robert wrote in his post Learning from the Masters – check that out to see some of their playing. For now, a tiny clip of John and Uwe from one of the sessions on tin whistle and flute playing Carolan’s Draught.

A couple of days ago we went over to the Beara to meet up with our friend Susan Byron, of Ireland’s Hidden Gems and her group of American tourists. Among them was Bob, who played us over the Healy Pass.

Finally, for something completely different, we travelled to the Beara again today to hear the wonderful David Syme in one of his legendary Living Room Concerts. If you ever get a chance to do this, grab it! Here he is playing the Chopin Etude “Tristess”. This is his own recording on YouTube, and if you Google David Syme and choose video, you’ll get lots more that will give you a flavour of what we heard this afternoon.

Among the pyrotechnics of Chopin, Schubert, Brahms, Bach and Gershwin, David told us a moving story about his Ukrainian-Jewish grandmother and played us a gentle piece called Jewish Prayer for Healing by Debbie Friedman. I will leave you with a short clip from his performance.