The highlight of last week was a trip around Roaringwater Bay in a traditional wooden boat, the Saoirse Muireann, visiting the Skeam Islands. Our captain was Cormac Levis, who led us last year on a trip to Castle Island and who is encyclopaedic in his knowledge of Roaringwater Bay.

Now, you may be tempted, as I was, to pronounce this The Skeems, but you can mark yourself out as a true local by referring casually to the Shkames. Called after St Céim (pronounced Kame), apparently, although this particular saint is surprisingly controversial, cropping up as Céin, Keane, or Kame, depending on the authority. THE authority, Pádraig O’Riain, in his Dictionary of Irish Saints is uncharacteristically silent on this saint, so we turn to the Mizen Journal for more information. The Mizen Journal was the much-missed publication of the Mizen Archaeological and Historical Society and it combined well-researched articles with lots of local lore. Bernard O’Regan was a highly-regarded local historian, interviewed by two others, Lee Snodgrass and Paddy O’Leary, before his death in 1994. In the interview he gave this account:

When St Ciaran left Cape Clear to go to the continent to be educated, he left his brother Kame and his sister in Cape [Clear]. Kame then built a wooden church on the West Skeam (Inis Kame, Kame’s Island).

The Bernard O’Regan Story Part 2

Mizen Journal No 4

Remember the bit about the wooden church, as we’ll come back to that.

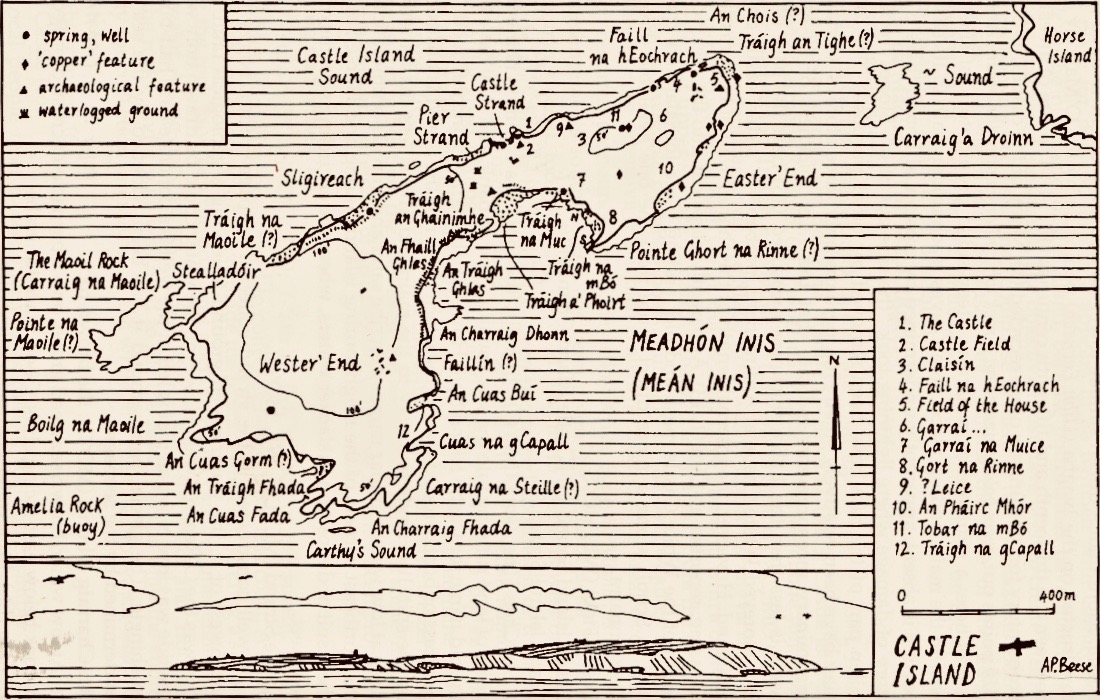

According to the geologist Anthony Beese, the West Skeam and the East Skeam were once probably joined, and possibly to Heir Island also, since the seas are very shallow between them. Based on geomorphological evidence, and Keating’s 17th century History of Ireland, Beese estimates that the islands may have separated due to storm activity some time between the 5th and the 9th centuries. Such a scenario, he says, would explain the lack of evidence for an early medieval settlement and burial ground on Heir Island.

His own interpretation of the placename is more prosaic – rather than being based on a saint, he speculates that the Irish word scéimh (pronounced shcay-ev) might be apt – it means an overhang, a projecting rim or edge. He says:

The attitude of the cliffs of the Skeam Islands is determined by the subvertical dip of bedding planes, and when walking over the ridges, the feeling is one of looking down from a high table, boats below your feet, the rocky shore hidden.

Anthony Beese

The Natural Environment and Place-Names of the Skeam Islands

Mizen Journal, Vol 8, 2000

The goats on East Skeam certainly appreciate the cliffs.

So take your pick – the Skeams are named from a saintly church builder from Cape Clear, or the name reflects the geology of the island. Which side are you on?

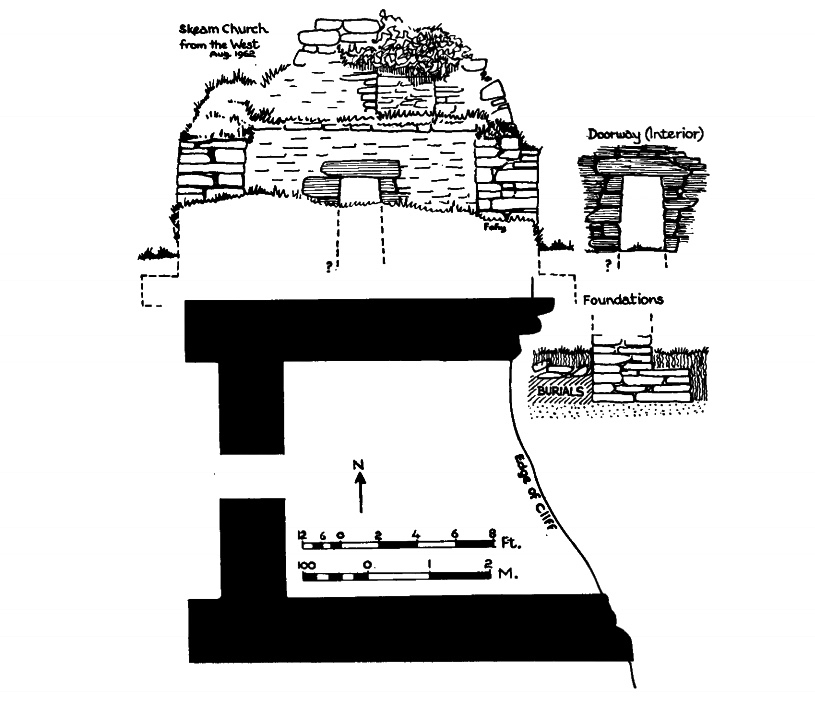

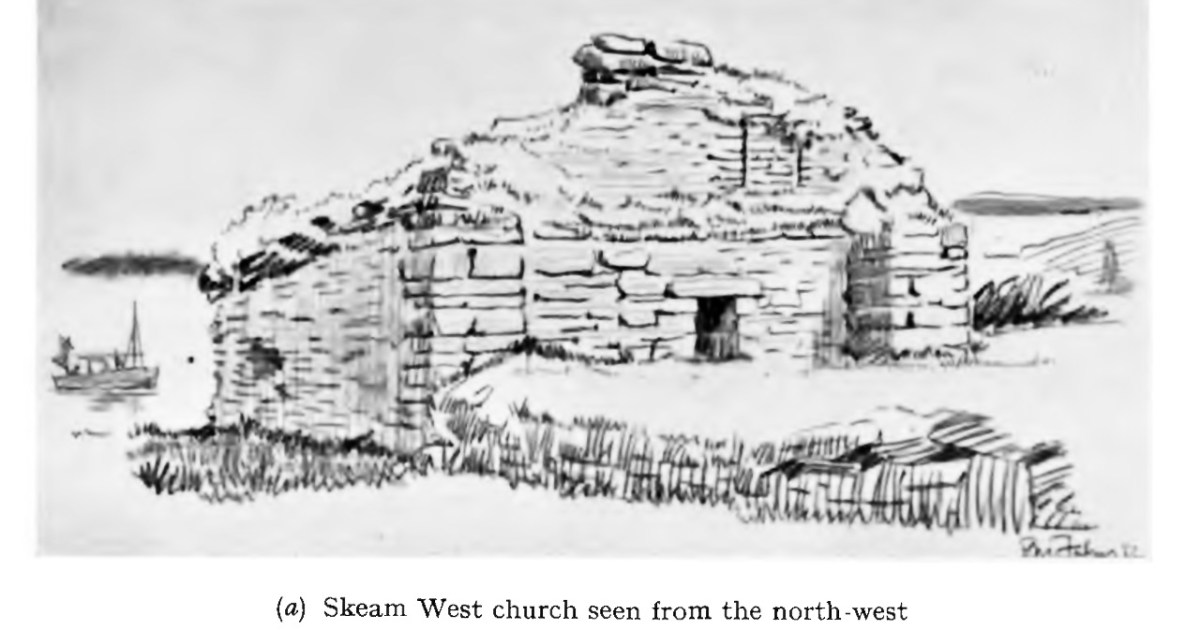

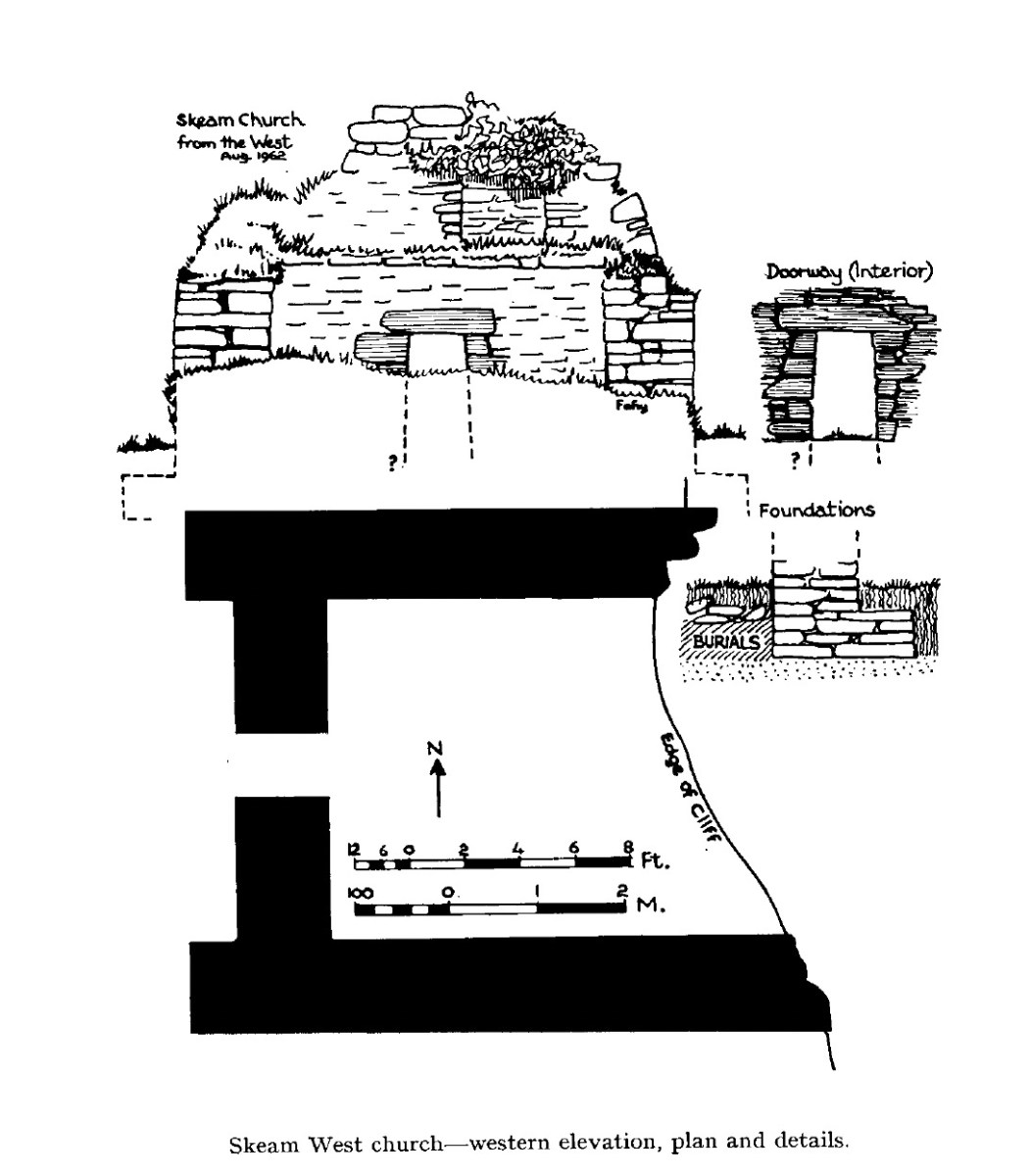

West Skeam has a fascinating history, as evidenced by the barely-hanging-on remains of an early Christian Church. It’s a small single chamber with antae and a splayed linteled doorway. In the photo above, courtesy of the Irish Times, it’s the small ruin on the bank halfway along the beach. Take a look at my post Irish Romanesque – an Introduction for more about this kind of early, pre-Romanesque Church. It is presumed that antae – the projections of the side walls beyond the gable wall – reflect an earlier form of wooden church in which those projections helped to hold up the roof and provide shelter over the entry. The survival of this feature is known as a Skeuomorph – an imitation in the stone-built form of the earlier wooden construction method.

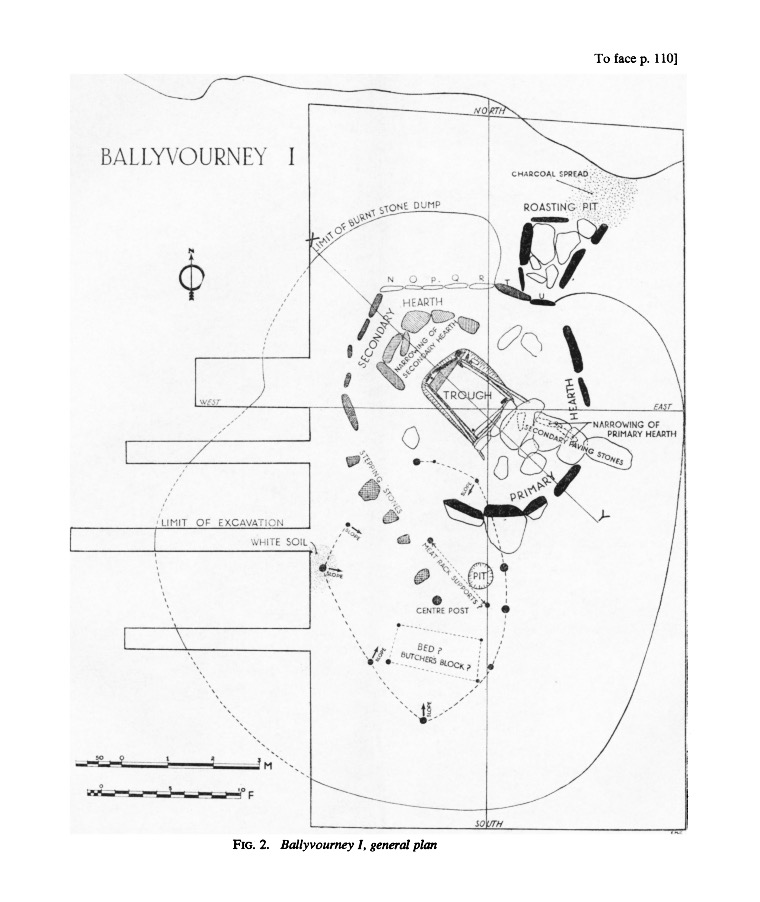

This little church is very significant – It’s the only one of its kind in West Cork. For many years it has been falling into the sea. Although once, Beese notes, it would have been high and dry, successive storms and the prevailing winds have eroded the bank it stands on over the centuries. Local people, Cormac included, tell of bones eroding out of the bank. The archaeologist Edward Fahy conducted a brief survey in 1962. The drawing above and one at the top of this post are from that report, and here is the conclusion:

Inhumed burials are visible in the cliff for a distance of almost thirty feet to the north and south as well as within the church itself where they are overlain by some soil and 18” of collapse from the walls. The burials extend downwards to foundation level of the building and appear to post-date it. The density of burials is not high and the skeletons are laid parallel to the axis of the church with their feet to the east. One grave is slab-lined but the rest are simple inhumations.

The architectural features of the church, dry stone building, simple doorway with inclined jambs and without architrave, the antae and the estimated length/breath ratio of the interior suggest a ninth century date for the structure. It is to be regretted that this, the only church of its date in the area is to be allowed to crumble into the sea.

Edward FahySkeam Island Church,

Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, 1962

A proper excavation was conducted by Claire Cotter in 1990, necessitated by a proposal by the OPW to build a wall to protect the church from further erosion. Here’s what the bank looked like when Fahy reported in 1962, and it was in an even more perilous condition by 1990.

Cotter published her findings in an article, Archaeological Excavations at Skeam West, in the Mizen Journal, Vol 3, 1995. The excavation was confined to the burial grounds – that is, the area outside the church itself. It revealed that burials had been taking place there long before the stone church had been built! In fact, radiocarbon dating of the first phase, containing 24 individuals, mostly adult males, assigned a date range of 430 to 770AD.

Phase 2, consisting of 15 bodies buried in the north side of the church, once again mostly adults, but this time one body could be identified as female. Rather than in body-shaped cuttings, some of these bodies had been placed in pits, and they were in a semi-propped up positions. These burials dated from 550 to 855.

This is what the church looks like now from the landward side. It’s very overgrown, but you can clearly see the antae and the linteled entry

Phrase 3 encompassed 33 bodies and dated from 1165 to 1395, after which the graveyard went out of use. Some of these graves may have had markers – a stone cross and notched stones were found.

Another interesting find, Cotter tells us:

In a number of burials the head was marked by small flat stones – generally one stone set close to the head on each side. This may indicate that the bodies had been placed on timber planking – the cradle stones would subsequently support the head and keep it in position when the timber planks had rotted away leaving a void within the grave. Remains of such timbers have been found in early medieval graves in England. In the case of Skeam, such timber planking could have formed part of a bier, perhaps used to carry the body on the sea journey. Two burials of newborn infants also belong to this phase and these had been placed on large stone flags.

It looks as if this burial ground was accommodating people from the other islands. Apart from a cillín on Heir Island, there are no burial grounds on East Skeam or on Heir. A midden to the south of the church contained lots of fish and shellfish remains, as well as fragments of seal and whale bones, and cattle sheep and pig bones. This activity dated to the 16th and 17th centuries.

Cotter, in her discussion, says the following:

There are no historical references to the church on Skeam west. It lies in the parish of Aughadown; and a decretal letter of Pope Innocent III [that’s him, below] issued in 1199 refers to “Aughadown and its appurtenances” and the Church in Skeam West may well have been included in these. Local tradition attributes the origins of some ecclesiastical foundation on the island to Ceim or Keims, a brother of Kieran of Cape Clear. This would place the foundation in the pre-patrician period and the site is therefore of great interest. Was the stone church built to replace an earlier wooden structure – perhaps destroyed by the storm which washed up the deposit of shingle visible at the north side of the present building?

. . . Small church sites such as Skeam were generally located within an enclosure which defined the termon or area of sanctuary of the church, and the ditch uncovered to the south of the church is probably the remains of such an enclosure. The question as to whether these foundations should be regarded as monastic has been much discussed in recent years. Some scholars suggest that these ecclesiastical foundations should be regarded as small church sites which provided essential religious services for the local community. Others would argue that the majority of these foundations began as monasteries and only later assumed a community role. In many examples the earliest burials are exclusively male and only at a later stage do we find mixed burial i.e. adults and children of both sexes.

. . . The burial ground at Skeam West appears to have been used over a long period perhaps as long as the 900 years. During its later history it may have been used by a wider community drawn from the neighbouring islands and coastal district as well as the Skeams.

She adds:

The human burials uncovered during the excavations were re-buried on the island in 1992 in what is hopefully their final resting place.

Above is the OPW wall, which seems to be doing the job of arresting erosion for the moment.

There’s lots more to tell you about the West Skeam Island, including fascinating details as to who owned it, and what life was like there. And we haven’t even arrived at the other Skeam Island, East Skeam, yet! Next time.

One final note – the island is privately owned and monitored by video link. A disembodied voice reminded us that we were trespassing, at which point we left.