In my original post on this site, Ballyrisode Fulacht Fia: Discovering a New Bronze Age Site on The Mizen, I described it as an intertidal fulacht fia (or water-boiling site). Subsequently, I wrote a paper for the Skibbereen Historical Journal on the site, and that paper can be read in full here: https://zenodo.org/record/3247880. This post will look at new information about this site in particular and fulachtaí fia in general. I give the original post in full further down, or you can read it, and its many interesting comments, here. If you haven’t read it before, it’s a good idea to do so before proceeding.

The photograph above was taken more recently and shows how sand carried in by the tide could, over time, bury these stones completely

In the original post and in the paper, I found parallels to the Ballyrisode situation in several other sites but particularly in the one at Coney Island in Connemara. The excavators concluded that this site was deliberately constructed to be inter-tidal – that is, to fill with water and drain as the tides advanced and receded. However, I have had the privilege of visiting the site anew with two geologists, Anthony Beese and Robin Lewando, and both are of the opinion that the site was originally on dry land. That’s Robin with the crossed arms, below, on an expedition to get measurements at the site.

Anthony Beese has studied the intertidal zones in West Cork and has concluded that the sea level has risen since the Bronze Age by enough to locate the trough on dry land, since it is barely covered now by water at high tide. Anthony also pointed out that a small stream was flowing from the land onto the sand nearby (below), which would have been a good source of fresh water for the trough.

The second piece of new information comes from a recent paper by Jennifer Breslin in Archaeology Ireland, Burnt Mounds – the answer is under your fingertips. In it, Jennifer posits that the mound, rather than being secondary to the trough, is in fact the primary focus of the site and is what is left after the production of charcoal. The troughs may have been used to produce tar, a bi-product of charcoal. This may explain why excavated fulachtaí fia have yielded very few food remains. Another intriguing take on these enigmatic but abundant sites.

Now here is the original post, published Sept 2018

Ballyrisode Fulacht Fia: Discovering a New Bronze Age Site on The Mizen

Hidden in plain site – that’s how we stumbled across a hitherto unrecorded archaeological site at Ballyrisode Beach. It’s a popular swimming place, often swarming with swimmers, sun-bathers and picnickers in the summer and enjoyed by dog-walkers in the winter. Like many others, we were simply enjoying being at the water on a warm day when Robert drew my attention to an odd grouping of stones.

Three sides of a rectangle were defined by stone slabs laid on their sides in the sand, while two other upright slabs stood close by.

It had all the appearance of a carefully constructed trough, with one side missing, and it immediately reminded us of the cooking site at Drombeg Stone Circle.

Drombeg – besides the famous stone circle there is a hut site and this – a water-boiling trough with associated hearth and well, surrounded by a horseshoe-shaped mound of stone. An interpretive panel illustrates its use.

I took photographs and posted them to an online forum with a request for more information. An answer came back immediately, from a group of archaeologists who had excavated an almost-identical site in Sligo – what we were looking at was indeed an intertidal fulacht fia (full oct fee-ah, pl: fulachtaí fia/full octee fee-ah)).

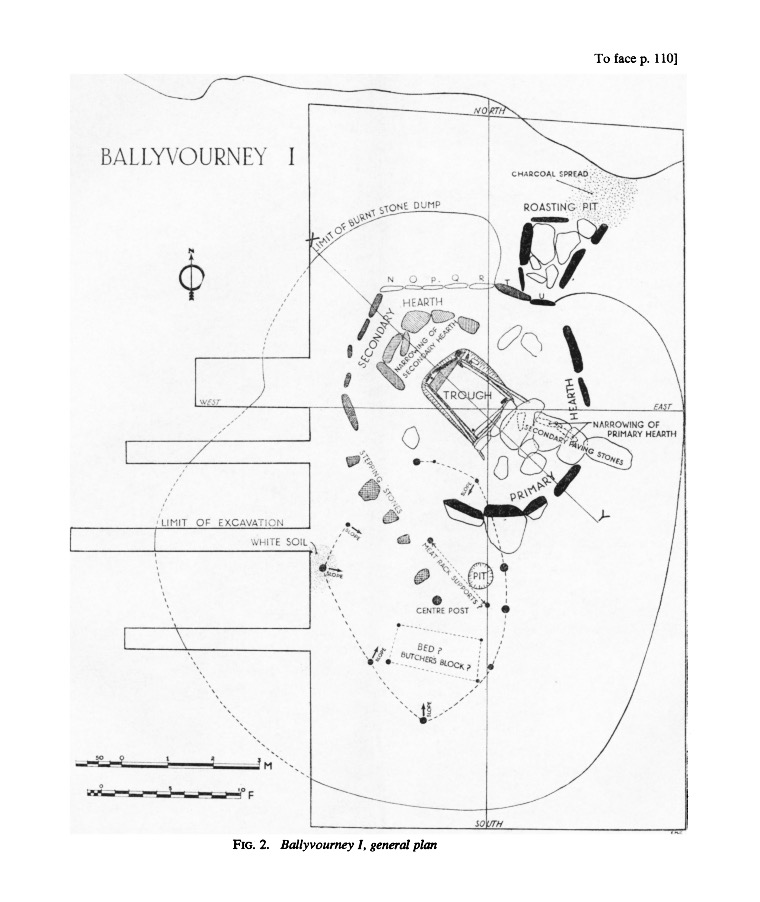

E M Fahy excavated Drombeg in 1958 and returned the next year to dig the fulacht fia. This is his site drawing of the fulacht fia. You can read his original report here.

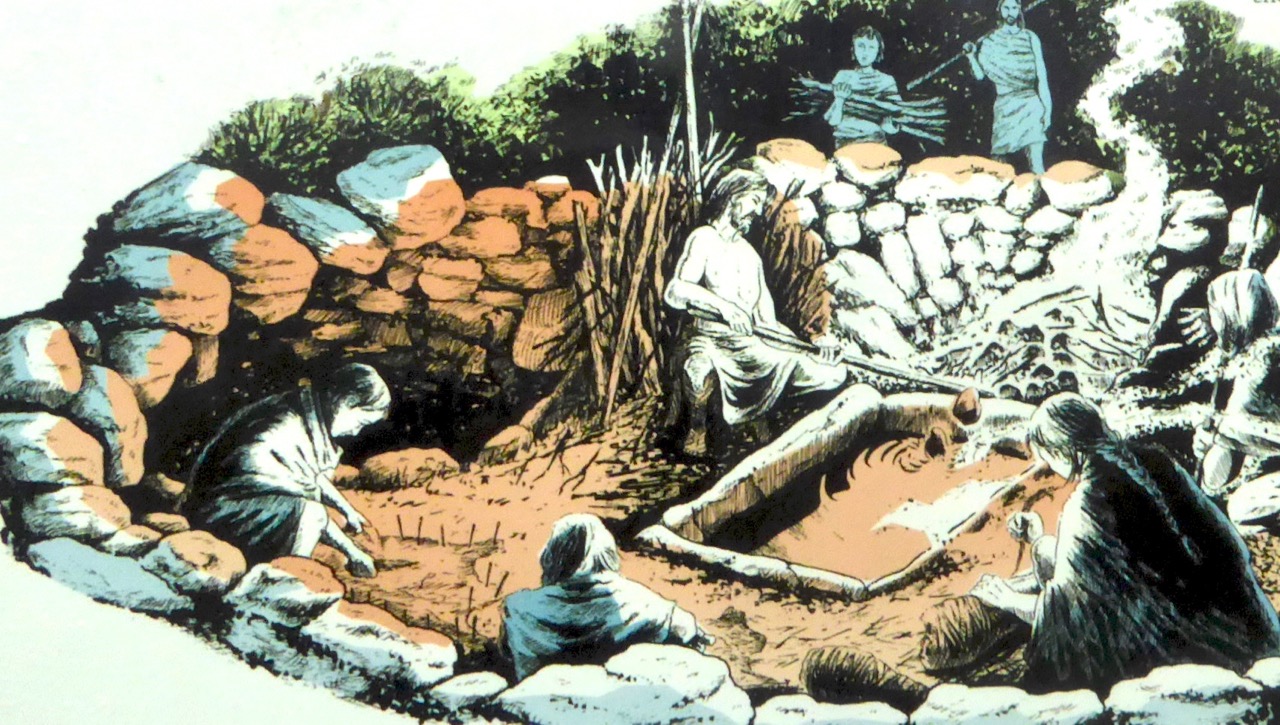

What exactly is a fulacht fia? The name translates as a wild cooking place and it was coined to describe this kind of open air kitchen. In Britain they are known as Burnt Mounds. Typically, they consist of a trough, normally lined with stone but occasionally with wood. The water in the trough was brought to a boil by dropping very hot stones into it, and therefore another feature of a fulacht fia is a hearth for heating the stones. Once the stones were used up (after heating and cooling one or more times they cracked and broke) they were tossed aside and over time a horseshoe-shaped mound of these burnt and shattered stones accumulated around the trough.

Another site drawing of a fulacht fia – this one was in Ballyvourney, excavated by Michael J O’Kelly in the 1950’s (report available here). Observe the numerous slabs laid on their sides around the trough – some for the roasting pit and some for the hearth. The two upright slabs at Ballyrisode are likely to have been part of such a related grouping of stones

Fulachtaí fia, in fact, are the most numerous archaeological sites in Cork, with 3,000 recorded sites, although they are known all over Ireland and in Britain and Northern Europe. Prof William O’Brien, in Iverni, refers to them as ‘water-boiling sites’ which is a more accurate description, since we don’t actually have overwhelming evidence that they were used for cooking. Few bones have been found among the burnt stones at some sites, although this is often explained away by reference to acidic soils and poor bone preservation.

Trinity Well, near Newmarket in North Cork, is a Bronze Age fulacht fia that has been re-purposed in modern times as a holy well! Read more about this site in Holy Wells of Cork

So the question remains open as to their purpose or purposes and proposals include their use for tanning and brewing. It is also possible they may have been used for bathing, or incorporated into sweat-house rituals.

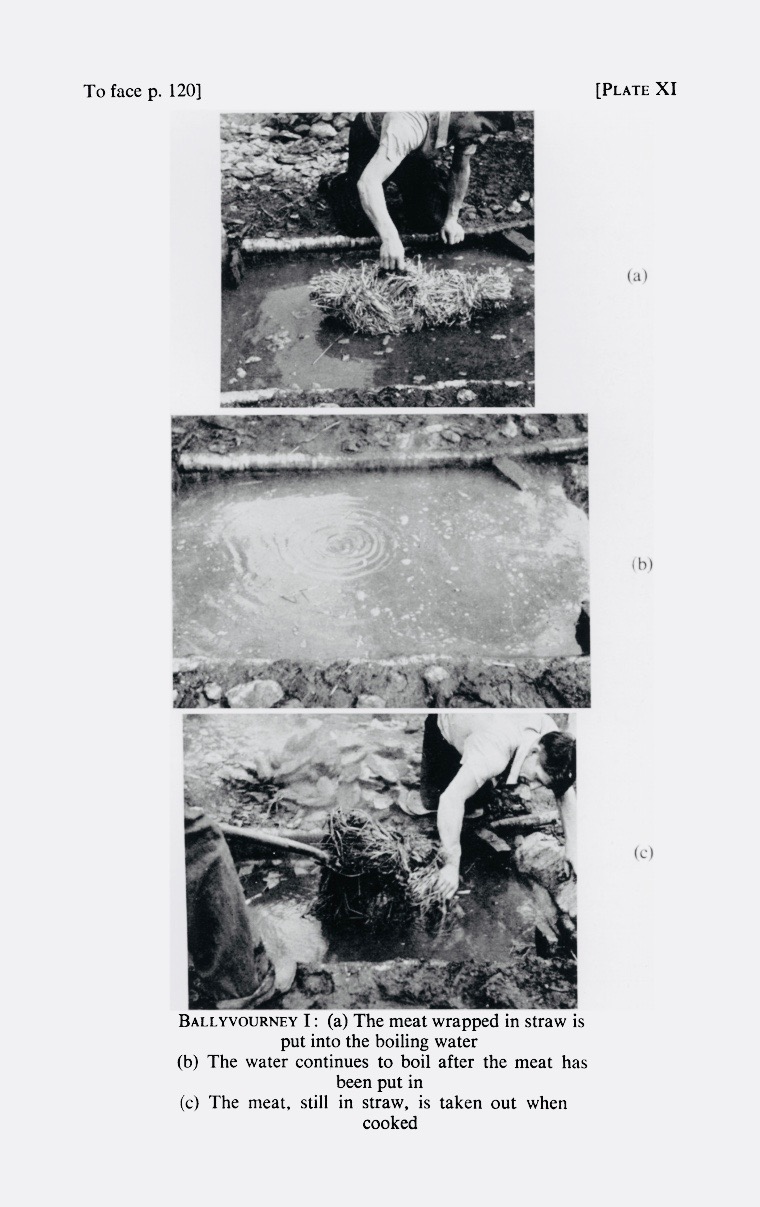

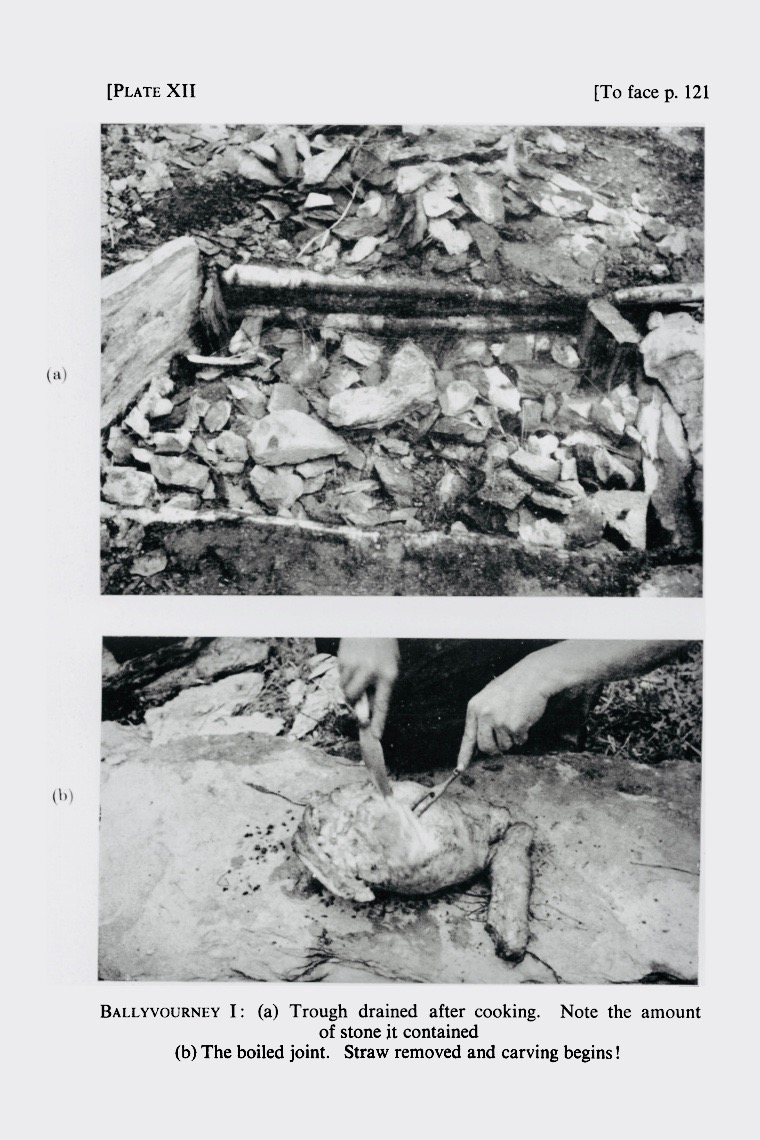

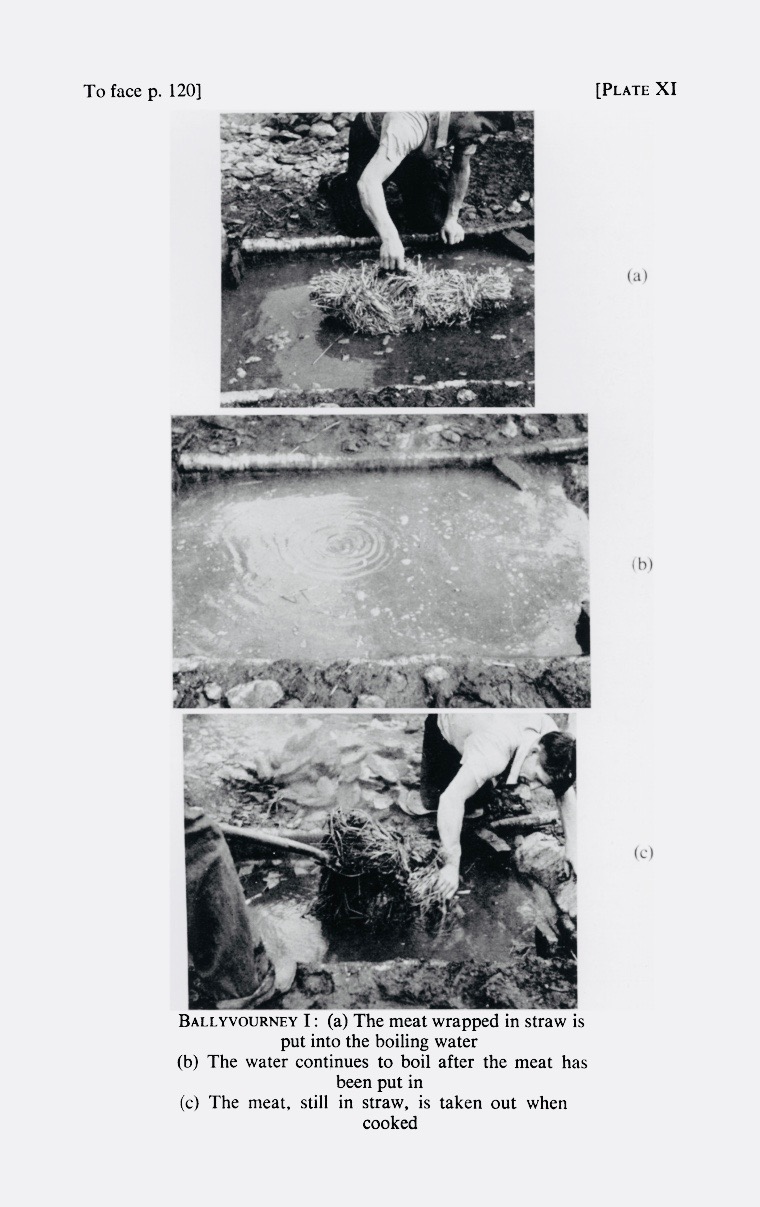

From Prof O’Kelly’s report on his excavations come these photographs of his cooking experiments

We do tend to think of them as cooking-places, though, largely because of the experimental work carried out by Prof Michael J O’Kelly in the 50’s. I remember him telling us about it when I was a student in his classes and I can still see the obvious relish with which he described the juicy leg of mutton that emerged from the simmering trough after almost four hours (they used the 20 minutes to the lb and 20 left over formula) and how clean the meat was when unwrapped from its straw casing.

But the brewing argument is compelling too – just take a look at this experiment by two archaeologists making ‘a prehistoric home brew!’

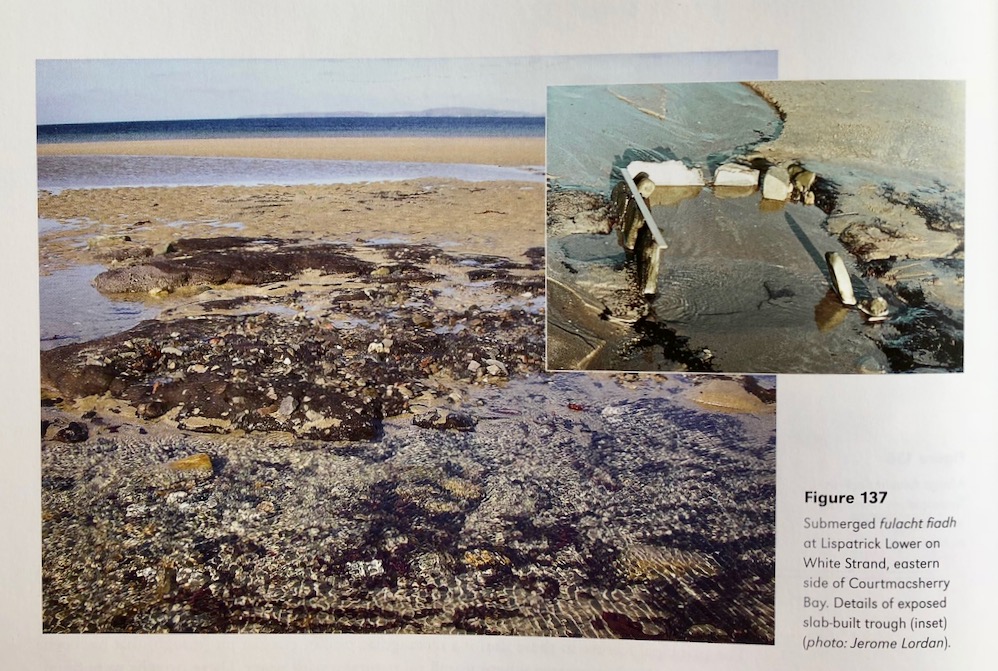

But what about a site like our one, half buried in the sand? It turns out that there’s a similar one in Cork at Lispatrick on Courtmacsherry Bay, that was visible when first discovered at low tide but underwater at high (see note from Jerome Lordan in the comments). Thanks to Alan Hawkes for alerting me to that one. Alan is the author of The Archaeology of Prehistoric Burnt Mounds in Ireland, the most comprehensive study of fulacht fia ever undertaken.

This photograph of the Lispatrick site is taken from Iverni

There’s another one at Creedon in Waterford (below) and that one is made of wood – thanks to Simon Dowling for sending me a 3D image of it (not shown), showing toolmarks on the wood

The wooden trough of the fulacht fia at Creedon Beach in Co Waterford, discovered by local historian Noel MacDonagh (photographer unknown)

Possibly the most helpful site to use as a comparison to Ballyrisode is the inter-tidal fulacht fia from Coney Island in Sligo. We are fortunate that the site was thoroughly analysed by James Bonsall and Marion Dowd of IT Sligo, and the results published in The Journal of Irish Archaeology in 2015 and available through JSTOR. (Thank you for the link, James Bonsall.) Ciarán Davis found the site and also participated in the excavation and he has kindly shared some of his photographs with me. Thank you, Ciarán!*

This and the following two photographs are of the Coney Island (Sligo) sites, kindly shared by Ciarán Davis

Like Ballyrisode, the trough is stone-lined and full of sand from the movement of the tide, which covers it at high tide. It was dated using a charcoal layer beneath the floor slab, to the Late Bronze Age (making it about three thousand years old).

The flat slab at bottom right has been interpreted as a kneeling stone – such stones have been observed elsewhere

The authors point out that it is impossible to tell whether the intertidal location of many such sites is a planned feature, or whether they were originally on dry land and have ended up in the intertidal zone due to erosion or shifting sea levels. However, at Coney Island it seemed clear that the fulacht fia had been deliberately constructed such that it filled with water at high tide and held that water for several hours afterwards. The presence of a nearby midden indicated that this fulacht fia may indeed have been used to boil fish and shellfish in salt water – an efficient (and delicious!) method of cooking seafood.

So there you have it – an exciting new discovery to add to the archaeology of West Cork! This summer has seen incredible new finds in the Boyne Valley, due to the unusually dry weather and the emerging technology of drone photography. While our find is not in the league of a Dronehenge, it’s always good to know that there is still lots to discover in the wonderful West Cork landscape.