We were unexpectedly in County Wicklow, and had a day or two of sunshine. To take advantage of this, we found our way up to the Great Sugar Loaf, with every good intention of climbing to its peak – 501 metres above sea level. I’ll come clean and mention that the starting point for the walk is already halfway up this elevation – and also we didn’t make it all the way on this occasion, as we were heavily overdressed! Only yesterday we still seemed to be in the grip of a very harsh winter, so had assumed that gloves, scarves and thick jackets would be the order of the day. In fact, quite a few other climbers were clad in tee shirts and shorts…

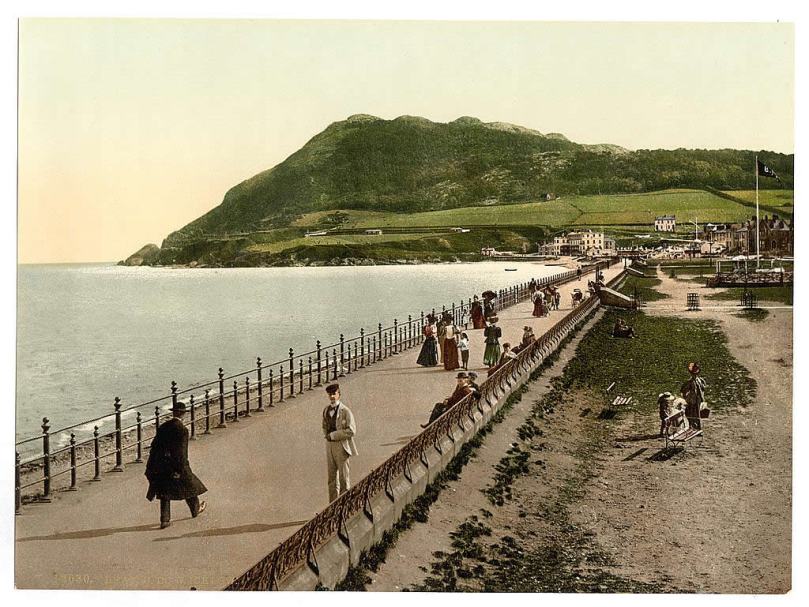

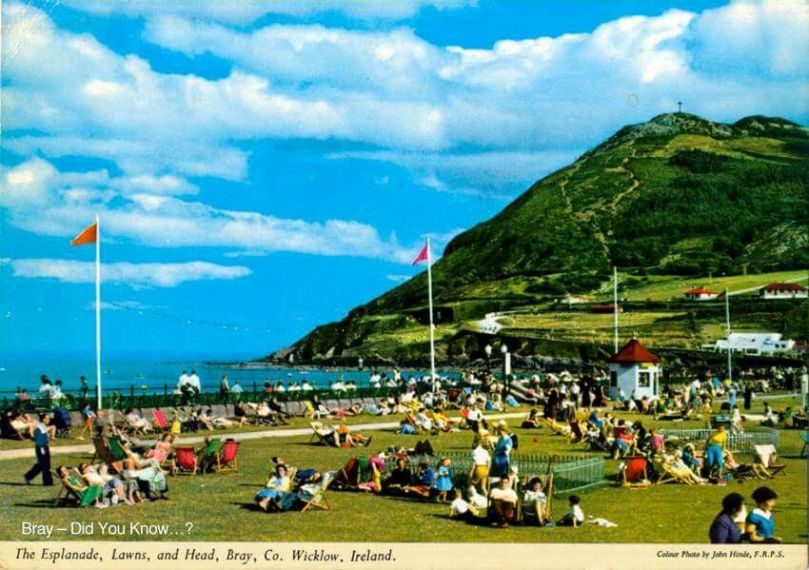

The upper view was taken on the path going up to the top – this morning. The lower view – taken a couple of years ago from Bray Head – gives a good impression of the Great Sugar Loaf (the furthest peak on the right) as the high point in a range, rather than a lone conical summit. There is also a Little Sugar Loaf which – in this view – is the high point in the central range in the photo. From other places, the ‘Little’ loaf also appears like a conical ‘peak’. Have a look at the pic below, where I have tried to show both ‘cones’ in the same view.

This photo, which dates from the early 1900s, is taken from the old beach in Greystones: the Little Sugar Loaf is over to the left, while the ‘Great’ one is at the left end of the further ridge (photo by William Alfred Green (1870–1958) – courtesy of Ulster Folk Museum). Below – the same view of the two ‘sugar loaves’ taken from the Marina, Greystones, today.

Here’s another view of the ‘Great’ loaf, with further pics of today’s adventures below, including the prospects from on the hill:

The area deserves considerable further exploration. The extracts below are from the Schools Folklore Collection, recorded in the 1930s: valuable commentary and memories collected from local inhabitants.

. . . If we were to visit Kilmacanogue over a hundred years ago it would present to us a very different appearance from what it does now. Our journey would be by the end of the Sugar Loaf Hotel of today, up the school lane, turning west for about a quarter of a mile and crossing the present day Rocky Valley road and following in a south-western direction along the foot of Sugar Loaf mountain. On our left was a church (in Brerton’s Garden) but not even the ruins of this remain. It is said the monks fled from this church in the Penal days, burying behind them their gold chalice, which still lies hidden in the field still know as the Church field. The road leading from Kilmacanogue to Kilmurry (now known as the Old Road) was the Coach Road between Dublin and Wexford. At the Kilmurry end there is a plot of ground about one acre known as Kilmurry Green which is believed to have been an old burial ground. The lane leading off from this road to the present main road near Kilmurry Dispensary locally known as Connolly’s Lane is supposed to have been lined with houses. The field on the North side of this lane (now in the possession of Miss Powell) is called the Street Field which indicates that a village must have been there at one time. The south part of Kilmurry Green contains the sites of two buildings – the stones, are still to be seen there, which marked the foundation of the gable. Traces of graves remain, though the place has not been used as a burying ground within any person’s memory . . .

Schools folklore Collection Kilmacanogue, Bray

Teacher: Caitlín Ní Chuinneáin

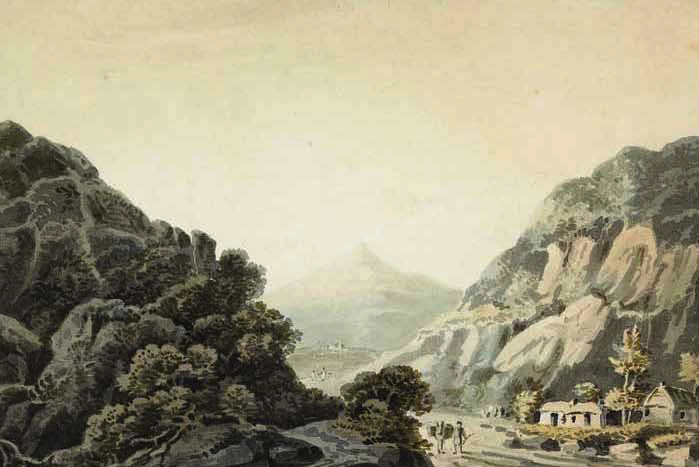

The Great Sugarloaf was a popular subject for artists. Examples are these watercolours: from Views of Bray and the Sugarloaf, County Wicklow, circa 1820 John Henry Campbell (1757-1828) – Whytes.ie. Back to the Schools Folklore Collection: we were particularly interested in the mentions of Red Lane, where there was evidently once a church, burial ground and holy well: it is said that none of these are visible today, but we will pencil in some further visits to have a closer explore.

. . . At the Southern extremity of Kilmurry bordering on Calary are two ruins which are popularly called Leghteampall or the Monasteries. These ruins stand in two adjacent fields, separated by a narrow lane (Red Lane). They lie east and west of each other in the Kelly’s and Whelan’s land, that in the west forming a square of thirty two yards each way. On the south side stands an angle of ancient wall built of stones and mortar 4′ 2″ high 2′ 2″ thick. There is a clump of stones and thorns at the north side 30′ long by 12′ broad and 2’2′ in height. There is an ancient holly tree in full vigour at the south-east angle a cross is cut in the tree and funerals stopped here and recited the prayers for the dead. About thirty yards east of there are the traces of an ancient church. A few stones of irregular shape remain in the foundation of the south wall; the stones appear to have been carried away from the north side within a comparatively late period. A heap of stones and rubbish occupies the place of the western gable, along which lies a large shapeless lump of a stone, having at the top a rudely formed cavity 7″ deep and 9″ in diameter at top, narrowing gradually to the bottom. This was a holy water stoup, one of the rudest ecclesiastical antiquities. An ancient decayed ash tree stands on the north of the church and graves may be traced in several places around it, though it has not been used as a burying ground for a long time. About a furlong south west of this place is a holy well called Bride’s Well (in Chapman’s Lane) at which Patrons were held, but none was held there within the last forty years . . .

Schools folklore Collection Kilmacanogue, Bray

Teacher: Caitlín Ní Chuinneáin

This winter scene is courtesy of Wiki Commons: we would like to visit at that time of the year, although the mountain may well not be hospitable then. Below – that’s the somewhat unusual gateway to the car-park at the Great Sugarloaf: take care when entering!