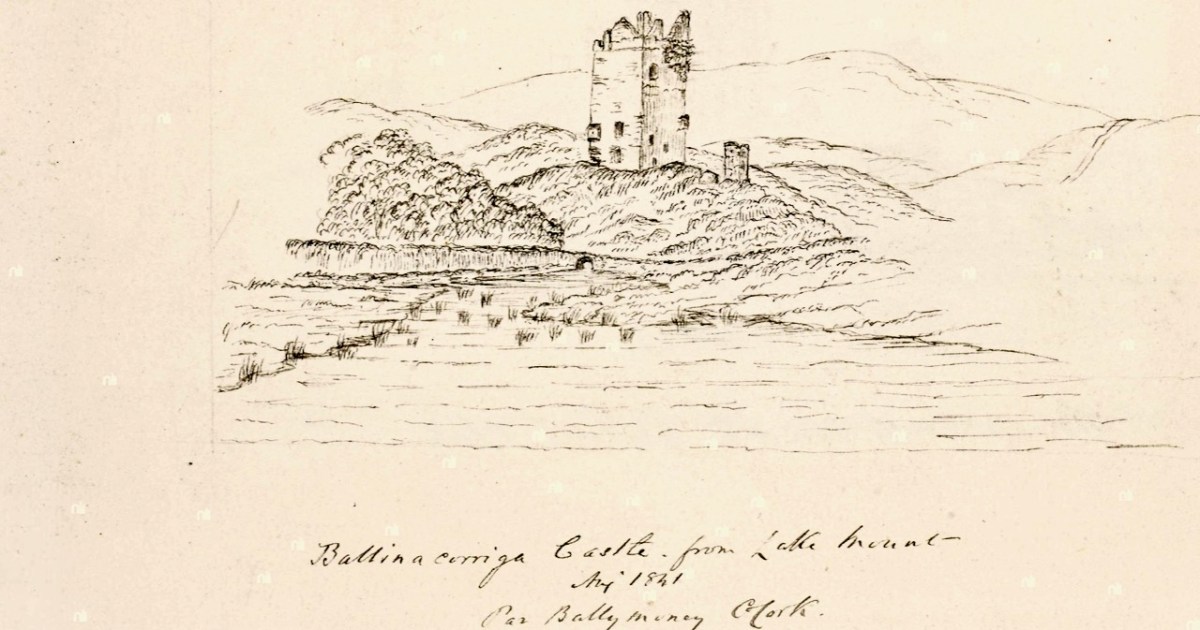

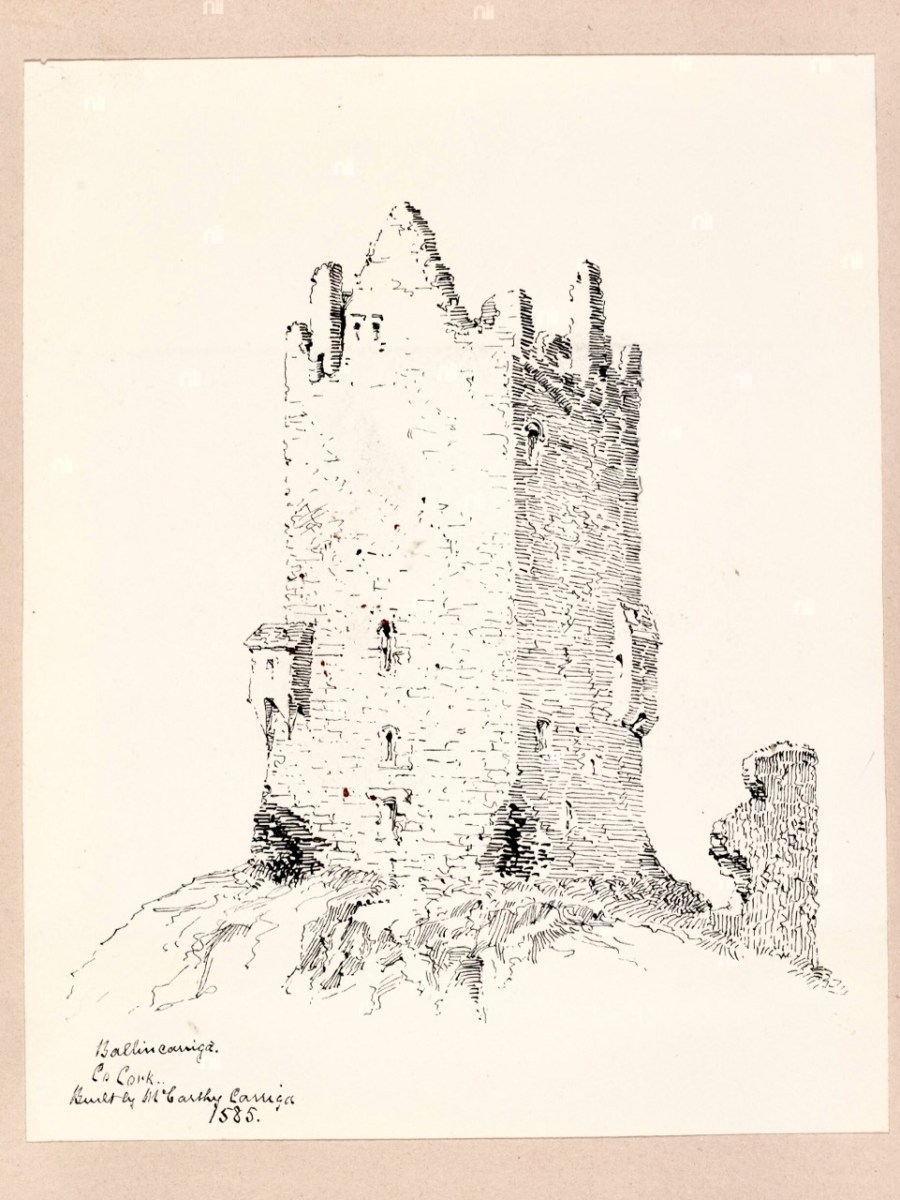

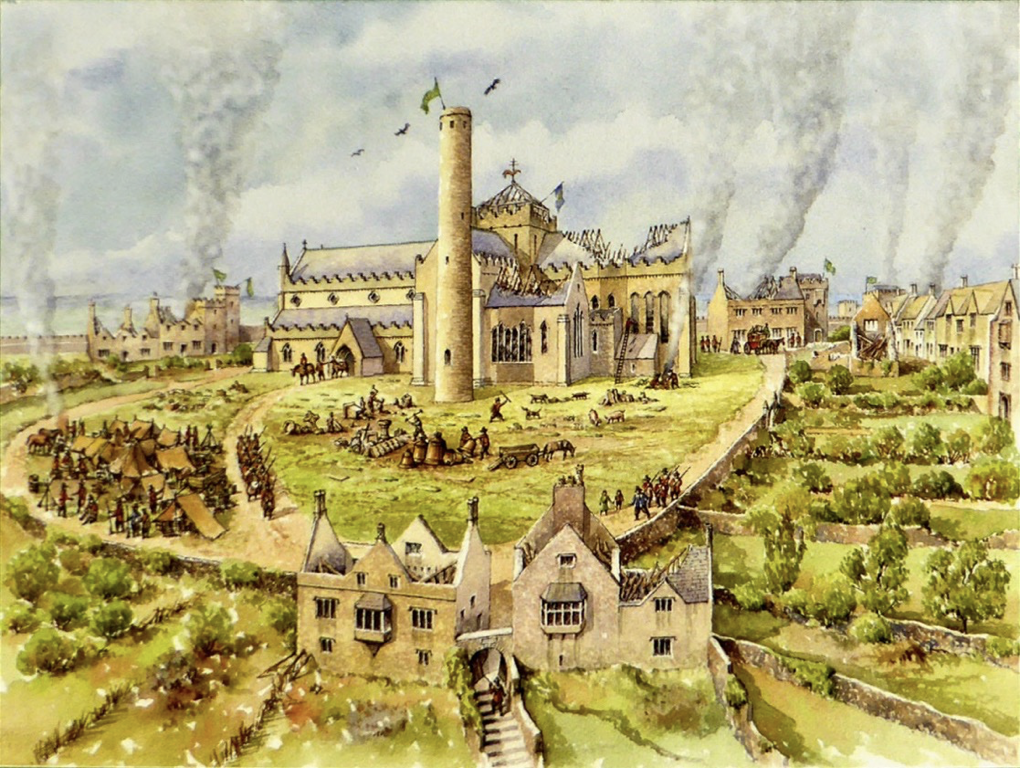

The romantic situation of Ballinacarriga Castle, and its relative intactness, meant that it was a favourite of antiquarians and travellers. There was a great appetite in the nineteenth century for images and accounts of all things to do with Irish antiquities – we were rediscovering our past and revelling in the realisation that we had a proud and significant heritage. Two of those illustrators, William Frazer and James Stark Fleming, visited and drew Ballinacarriga for their series on castles and other antiquities. Fleming, a Scottish solicitor and a constant visitor to Ireland was an accomplished watercolour artists and architectural historian. In all, he produced 10 volumes of drawings of Irish castles*. His sketches ( like the one below) were made on the spot.

William Frazer was also a prolific illustrator but his sketches were sometimes based on other drawings (such as by du Noyer) or on photographs. His interior scene is a lovely wash. Both the lead images are by Frazer, and the Fleming and Frazer drawings are included here courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

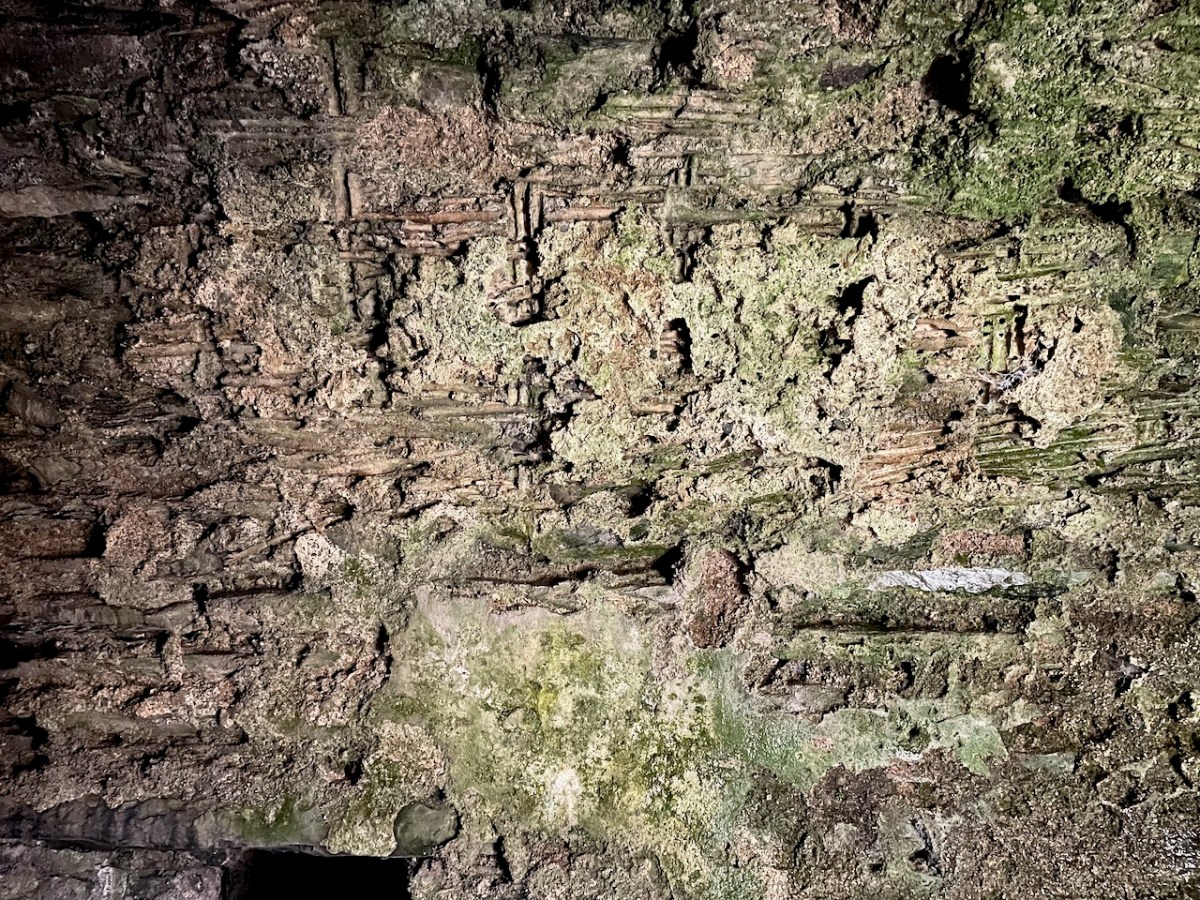

And yes, the interior – let’s go back inside the castle (see Part 1 for the exterior). Before we leave the level under the vault, let’s take a look at the interior render, still in place on the walls. It’s a reminder that those walls would have been lime-rendered in white, which would really have helped with visibility inside.

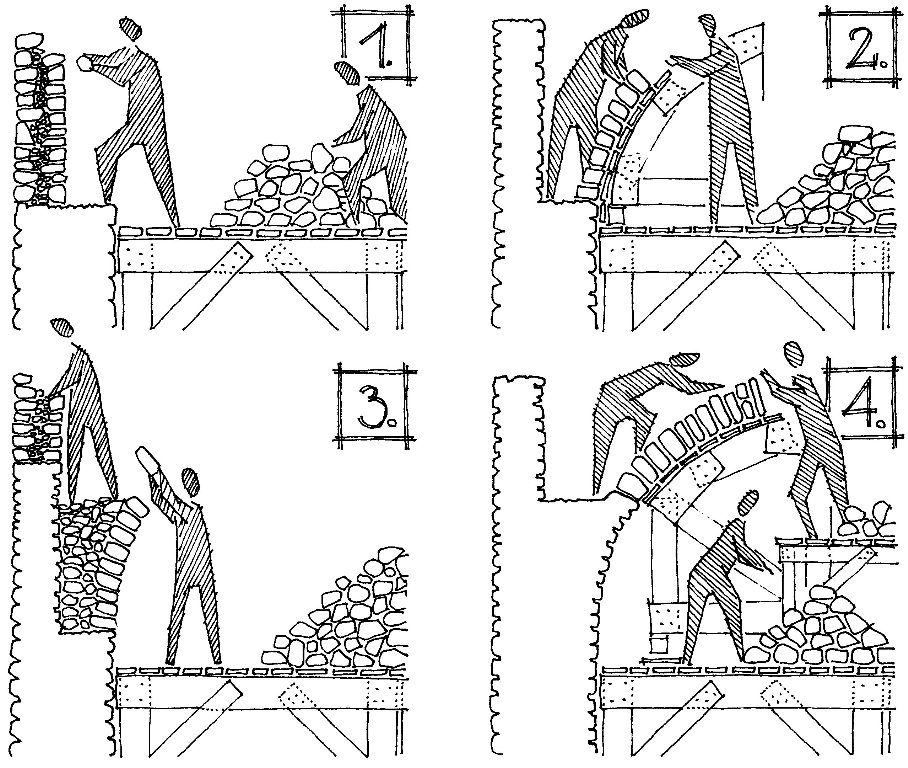

A mural chamber (room within the walls) at the top of the stairway also has a vault and here we can see exactly how the vault was constructed.

A scaffolding of wicker was erected first and a layer of mortar laid on top of that. Ceiling stones were laid on the scaffold and mortared into place and then the stone work was built up to provide the floor of the next story.

When the scaffold was dismantled the impression of the wicker was left on the mortar – and in this case it looks like some of the wicker stayed behind as well.

Another mural chamber contained the castle’s indoor plumbing. In the last post we saw the exit of the garderobe chute. Here is the garderobe itself – it would have had a wooden seat for comfort.

Another way of getting rid of rubbish was to have a slop chute and there is one here, close to what may have been an interior cooking area.

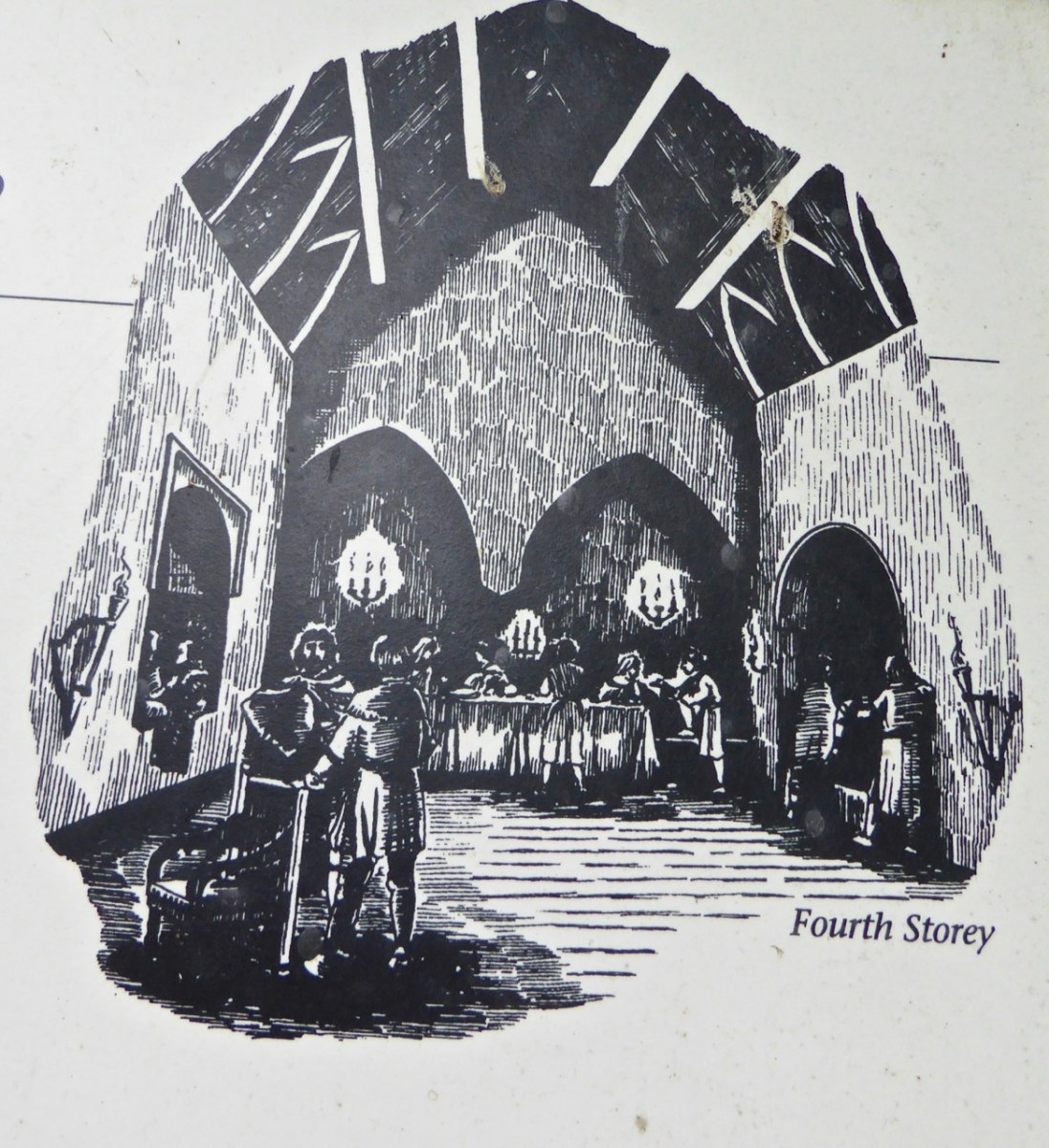

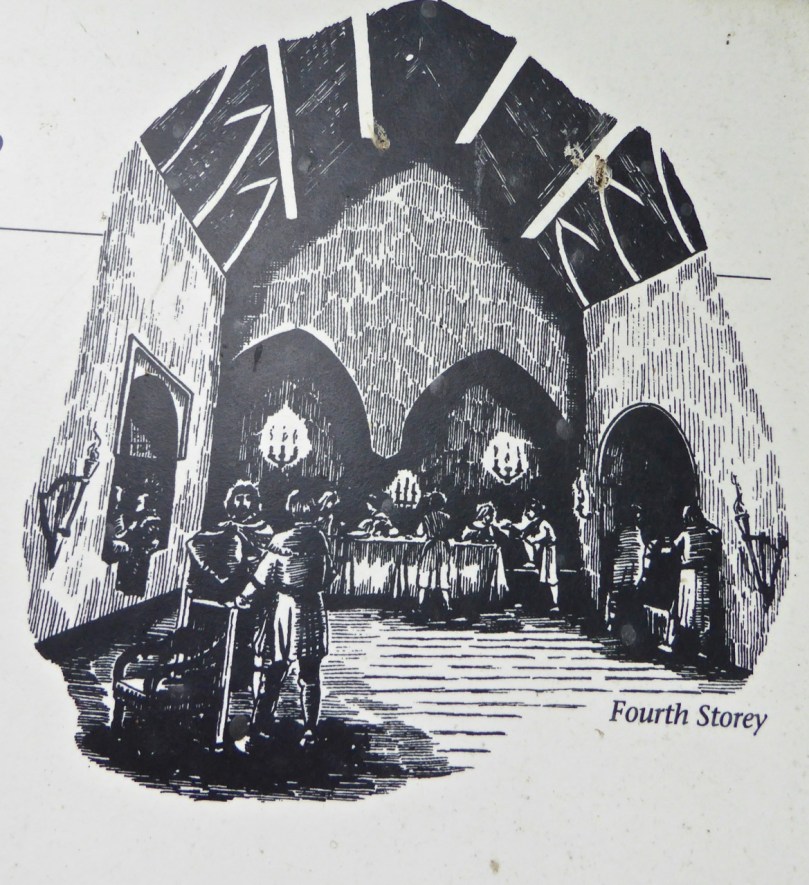

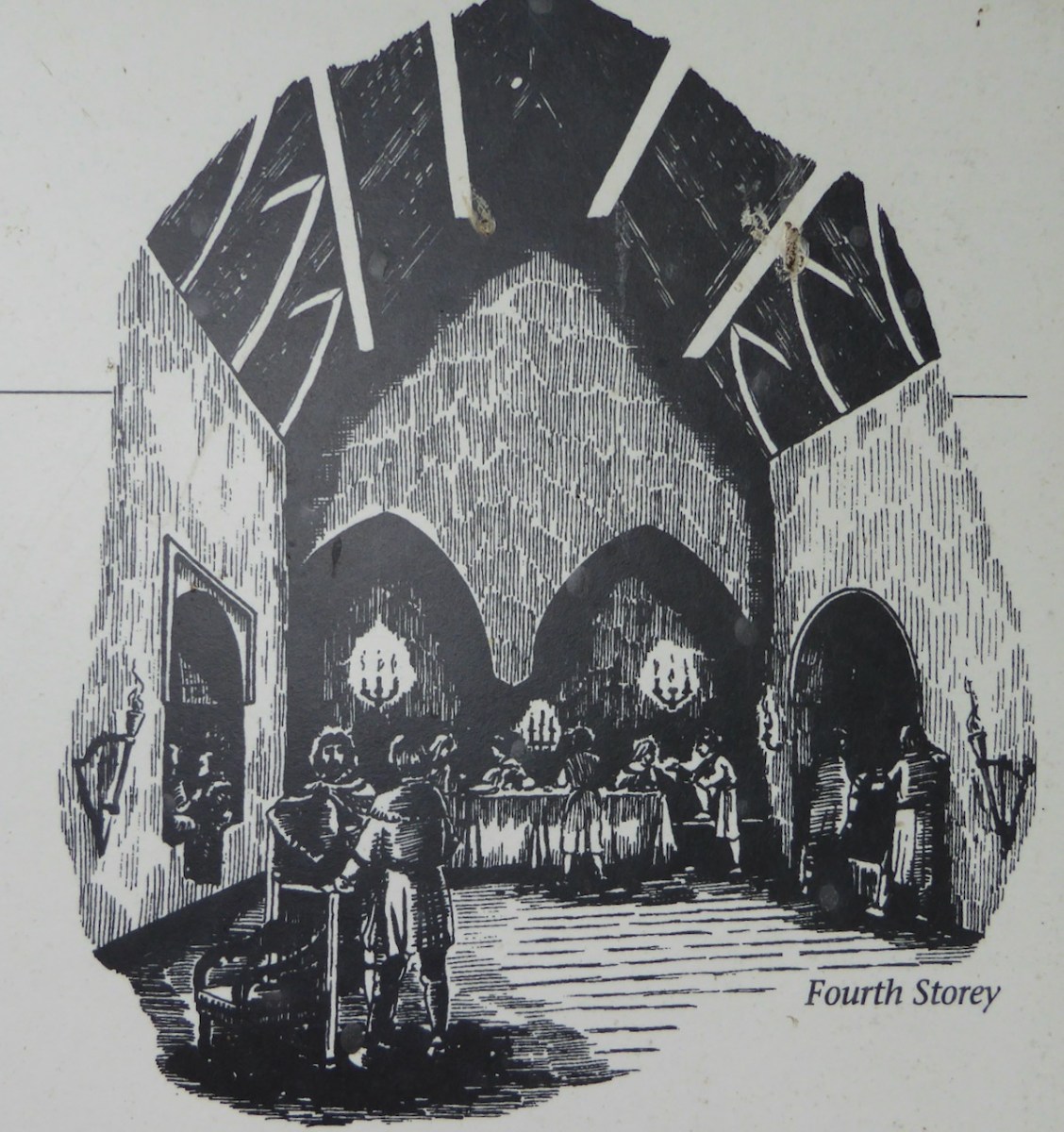

But the real glory of the castle is the top floor. The function of this chamber, sometimes called a solar, was for the chief and his family to entertain visitors and to conduct business.

Hospitality was an important obligation of all the great Irish houses and a drawing on the information board at Ballinacarriga shows how this room may have been used for feasting and discussions.

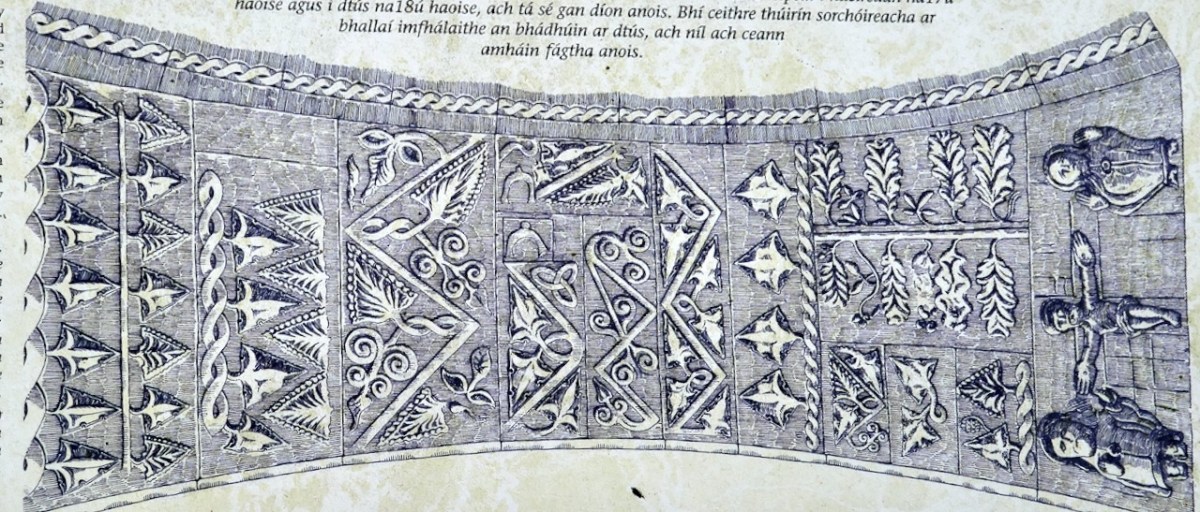

And here we meet more carvings – yes, there are two more window embrasures with carvings on this level. On a window on the north side there is an inscription that gives the date of 1585, and the initials R.M. C.C. for Randal Muirhily (Hurley) and his wife Catherine O Cullane (we met Catherine last week). So this is likely when all the carvings were done.

This room may also have been used as a private chapel. The clue is in the nature of the remaining carvings. The window on the South side has a crucifixion on the east end, but the whole surround is carved with stylised foliage and scroll patterns. While it is difficult to photograph this, the information board has a great illustrations (even if backwards from how it is viewed).

The crucifixion and other religious iconography (more of that in a minute) is a remarkable and unique element in this castle. After the Reformation got underway, and starting around the 1530s iconoclasts destroyed anything in the way of religious representational art they could get their hands on. It’s the reason we have no Medieval stained glass left in Ireland. That’s right – not a single window, nothing but a few scraps of glass that have turned up in excavations.

Crucifixion images were particularly anathema to the Protestant reformers. What survived those rampages fell victim to the Cromwellian Puritans from the 1640s on, like the destruction of St Canice’s Cathedral above – once renowned for its great East Window.

The location of the Crucifixion carving is probably the key to its survival — tucked inside a West Cork tower house, it was simply inaccessible to reforming zeal. And the date of 1585 is actually rather bold, coming right in the thick of the Elizabethan push. It could even be read as a deliberate act of Catholic defiance by the Hurleys, which adds another layer of significance.

The crucifixion scene actually looks a little archaic – more like a Romanesque carving than a 16th century one. That may have been because local craftsmen were working in a persistent native tradition rather than following Continental Renaissance trends. Jesus on the cross is flanked by Mary and John. The carving is naive, the hands are disproportionately large and the feet are pointing sideways. There is a checkerboard pattern as background. I have provided a black and white image as well as the colour photo, in case that helps.

Equally intriguing is the Arma Christi, or Instrument of the Passion panel on the opposite (north) wall. This is a motif that is also familiar from much later 18th century headstones. It was a particular favourite of the Franciscans, and the Hurleys may well have had good relationships with the friaries in Bantry or Timoleague, and a Franciscan confessor (pure speculation on my part).

While I have seen assertions that the top panel features images of Mary and St Paul, I have pored over them and see only the familiar elements of the Instruments of the Passion. From left to right, on the bottom panel (below) I see the pillar and ropes used to bind Christ, the ladder, the crown of thorns, the hammer (with a hammer end and a pincer end), and a heart pierced by crossed swords.

On the upper panel (below) I see the cock and the pot, the spear, a nail behind the spear, the crucified Christ, and the flail. The thing that looks like a boot to the left of Christ has me stumped, as do hints of other elements. It looks like a checkerboard background is used, which would indicate it is of the same exact vintage and by the same hands as the crucifixion on the opposite window.

Please – dear readers, tell me what you see – I love to be educated and corrected in these matters. Apparently, this room was used as a chapel by local people. The author of the piece in the Dublin Penny Journal says Up to 1815, (when the chapel of Ballinacarrig was built,) divine service was performed for a series of years in the hall of the castle. There is a strong local tradition that that was, indeed, the case. By the way, the whole piece in the 1834 Dublin Penny Journal is highly improbable and equally entertaining. You can read it freely here.

Ballinacarriga Castle is in many ways a typical West Cork 15th/16th Century tower house. What make it unique and a national treasure are the carvings, and the hints they give of a secret life away from the prying eyes of the conquerer.

* Available here: https://catalogue.nli.ie/Collection/vtls000245965