A cold and clear January day is just the ticket for a trip to the Northside of the Mizen. While Robert writes about the life of Northsiders, I want to look specifically at the area known as Dunbeacon. On rising ground that ascends to Mount Corrin and overlooks Dunmanus Bay West of Durrus, Dunbeacon offers spectacular views and lots to explore.

Looking across to The Sheep’s Head at the head of Dunmanus Bay, near Durrus

In the last few years the Sheep’s Head Way has expanded into parts of the Mizen Peninsula. This is a very welcome move and the SHW committee is to be commended on taking this initiative. Today we followed part of this new trail through Dunbeacon townland and were rewarded with glimpses of the past, lovely vistas, Caribbean blue seas – and biting cold!

This section of the trail runs along a scenic boreen

Dunbeacon is synonymous with the Stone Circle that carries its name. Robert and I have visited it on a couple of occasions in the past. We have knocked on the farmhouse door for permission to cross the land to get to it and never found anyone home. We proceeded anyway, albeit slightly nervously as it was an obvious trespass on a working farm. The stone circle is sited on a small plateau with views east and south to Mount Corrin and Mount Gabriel, although rising ground to the northwest obscures Dunmanus Bay.

Mount Corrin: a large cairn on top can be seen from many miles away. We have walked up to this cairn – see our account of it here

The circle is incomplete so it is difficult to know exactly how the builders intended its orientation as the portal stones and recumbent are missing. It may have had a central monolith. (For a complete explanation of Stone Circles see our post Ancient Calendars.) However, the clear view to the east and south horizons are design features that link it to sunrise and moonrise at certain times of year.

This photograph of Dunbeacon Stone Circle, and the one that heads up this post, were taken before the access trail (described below) was built

Intriguingly, Michael Wilson, of the Mega-What Website, says that practically the stone circle is really half a monument: what it takes to complete it for calendrical purposes are two other elements across the valley in Coolcoulaghta, a standing stone (now gone, but its position is known) and a standing stone pair.

The Coolcoulaghta standing stone pair, with Robert for scale. These stones were knocked down in the past but re-erected following a local outcry. Access and parking are now provided

Having studied the area carefully, Mike says, This site [the standing stone] combines with the Stone Circle 400m away at Dunbeacon to enable observations of the lunar nodal cycle in all four quadrants as well as giving complete all year round solar coverage. It thus seems likely that the Standing Stone was an original outlier to the Stone Circle and that the Stone Pair was added later, probably by a different group of people, in such a way as to make a minor technical improvement.

It’s further than it looks in this picture, but there is a clear view to the stone circle from the standing stone pair. In between is the most annoyingly positioned electricity pole in Ireland

As part of the development of the new walking route, the SHW group has negotiated access to the Stone Circle, and has, in fact, built a fenced trail across the fields and up to the circle. This, of course, is excellent in that it finally provides open access to this wonderful site. There is, however, a problem: the stone circle is now surrounded by a wooden fence on all sides that severely impacts on the appearance and atmosphere of the site. While it will keep cattle away from the stones (cattle can do a lot of damage to sites like this) and provide a safe zone for walkers if there are animals in the field, it has become impossible to relate to the site in the same way as we used to.

The last section of the fenced trail. The fence around the stone circle can be clearly seen now

The author of the Facebook Page Walking to the Stones expressed himself thus when he saw the new enclosure: “The wire fenced avenue turns into a wooden fenced coral. The stones, imprisoned in a begrudgingly small pen. The wildness has gone, the mystery has gone. You might just as well be standing in a sterile museum environment. What have they done?” His comments generated a chorus of agreement.

Indeed, it is hard not to look in dismay at a fence like this. It makes taking photographs of the whole circle well-nigh impossible. It creates an overwhelming visual barrier between the circle and its surroundings. As an erstwhile archaeologist, I also have to wonder what was disturbed as the post holes were dug. And yet, all of this was done with the best of intentions, and it has succeeded in providing public access to the site. I would be interested in our readers’ thoughts.

It is quite difficult now to get a photograph of the entire circle. This one is partial, and shows a clear sightline to Mount Gabriel

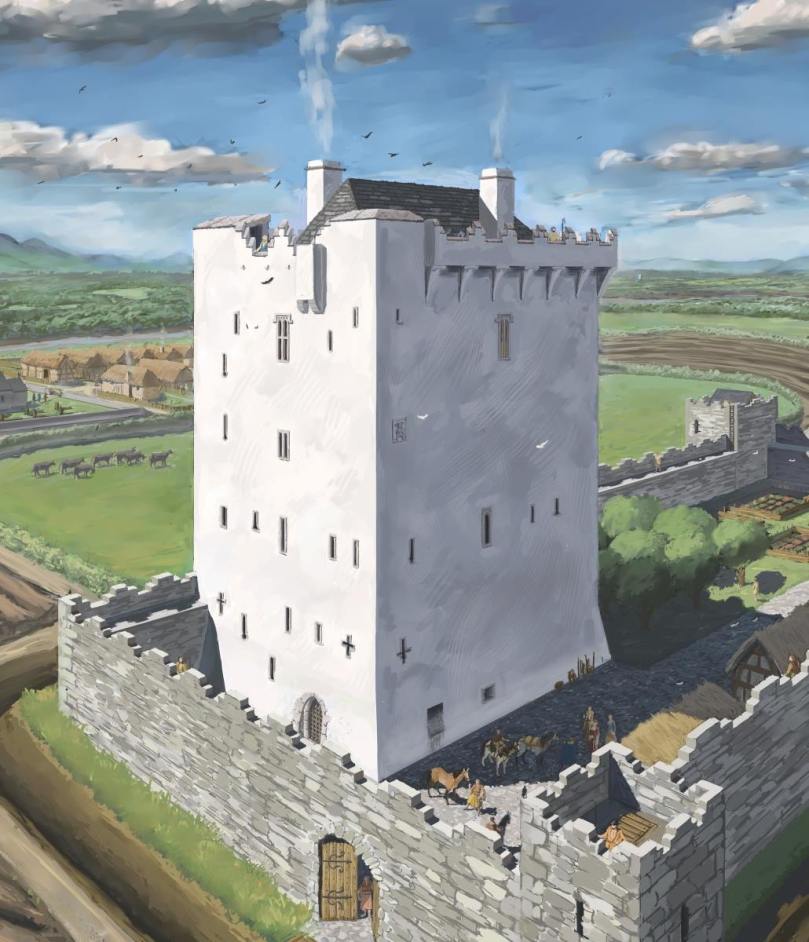

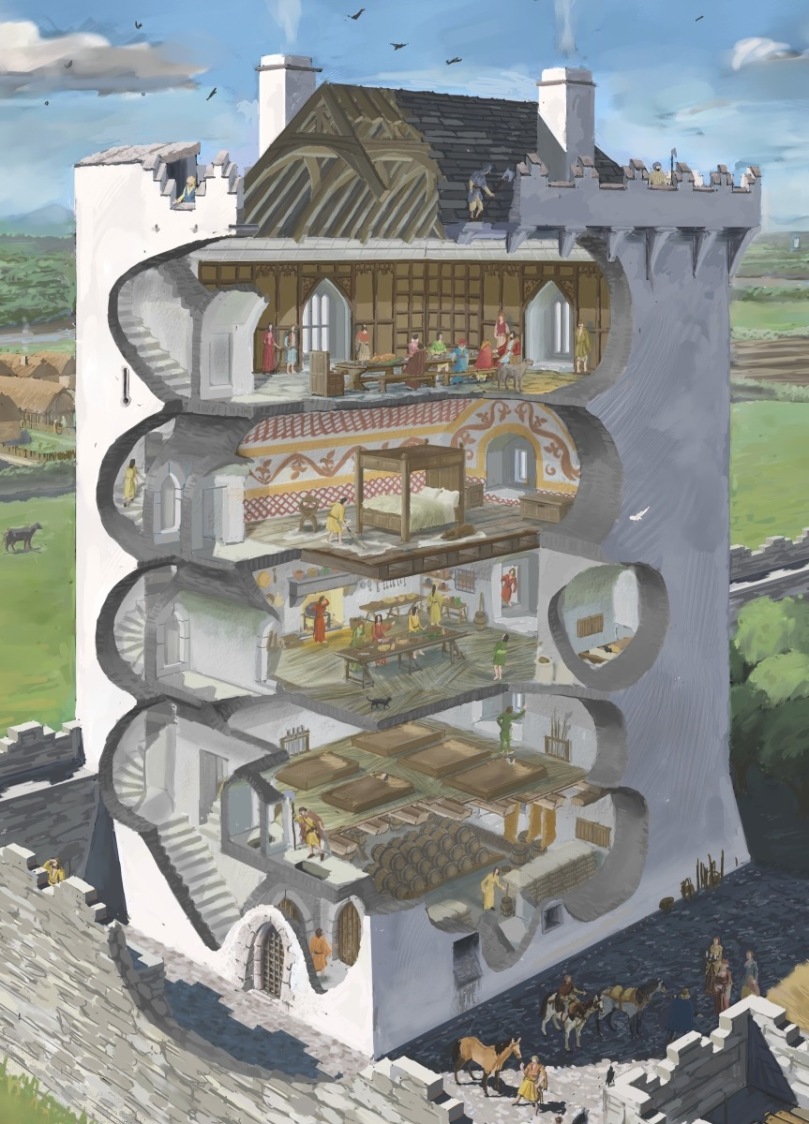

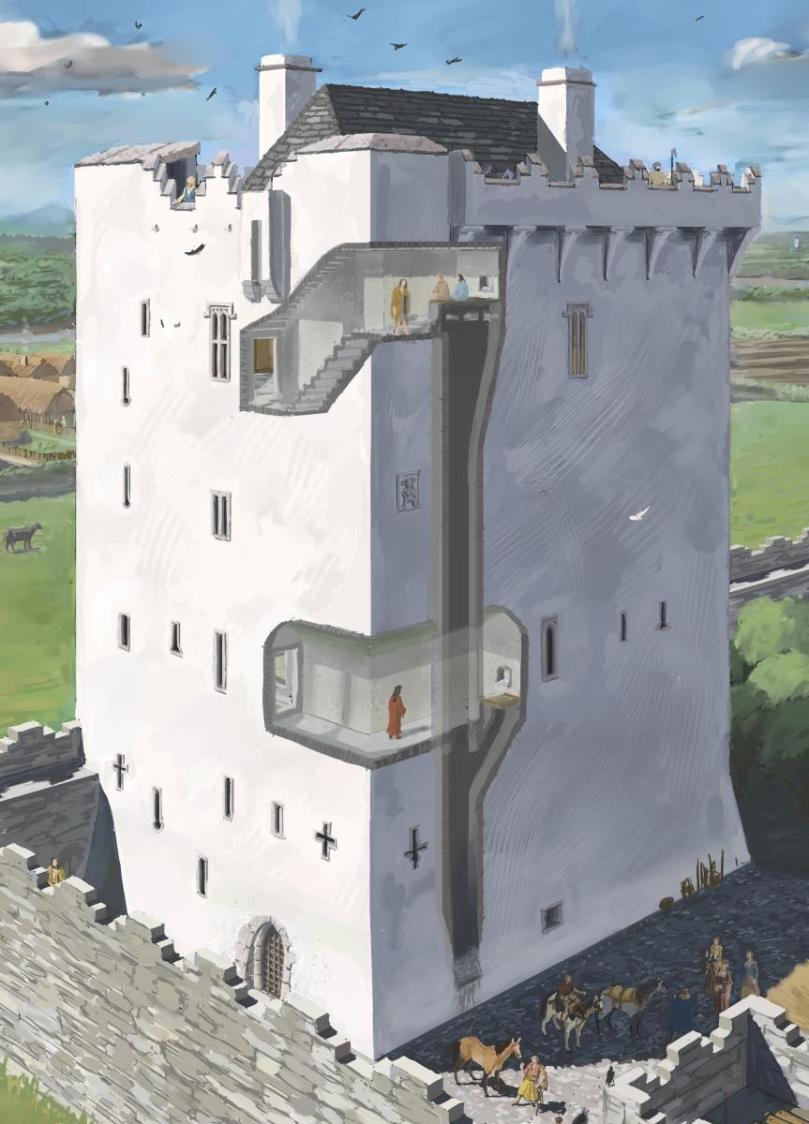

Before we leave Dunbeacon, I can’t resist a quick trip down to what’s left of Dunbeacon Castle. One of a string of O’Mahony Castles on the Mizen, this tower house once guarded the head of Dunmanus Bay. Its siting is strategic – no ship was going to penetrate to the head of this bay without being in clear view of this stronghold. The O’Mahonys controlled fishing and trade in this area from the 12th to the 16th centuries and became fabulously wealthy in the process.

What’s left of Dunbeacon Castle

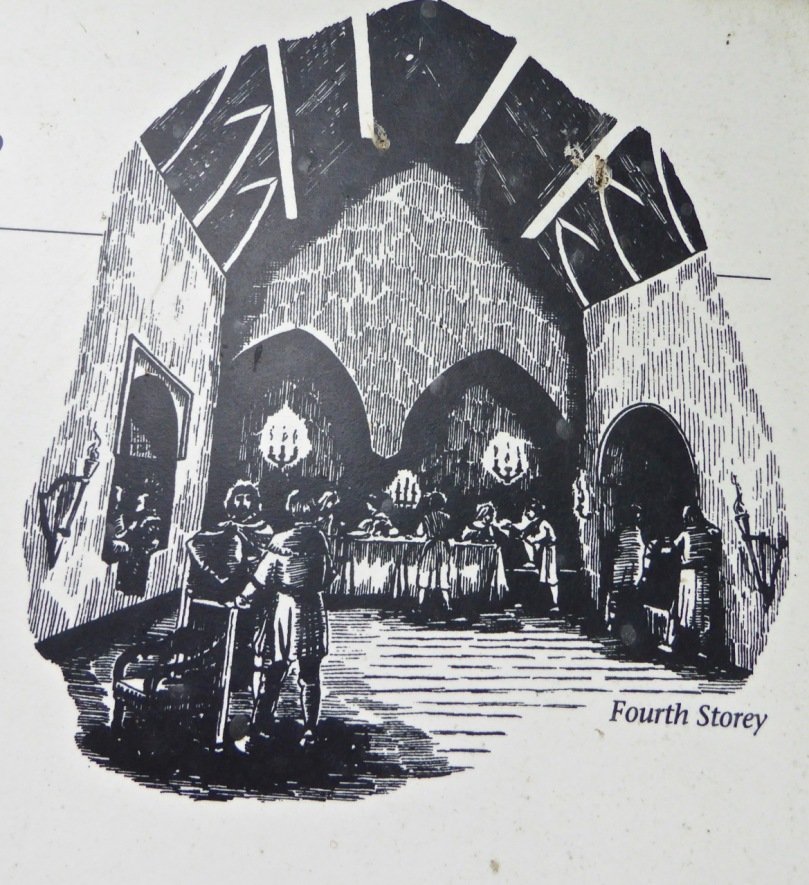

This castle would once have been the dwelling place and administrative centre of a powerful chief. He would have hosted banquets where his poets and musicians entertained the guests with stories and song. Alas, after the Battle of Kinsale all the O’Mahony tower houses in this area were taken by the British and many that were left standing were dealt a final blow by Cromwell’s cannon.

Not much left – but what an incredible position!

The centuries pass. The old Mount Corrin mines are no more. The sizeable population sustained by potatoes was devastated by the Famine. Now the land is grazed by cattle and sheep and a few farm houses dot the landscape. It is a peaceful and beautiful place. Do the walk – you will be in the footsteps of farmers and chieftains, of herders and megalith builders and astronomers, of miners and fisherfolk who have called this place home for thousands of years.