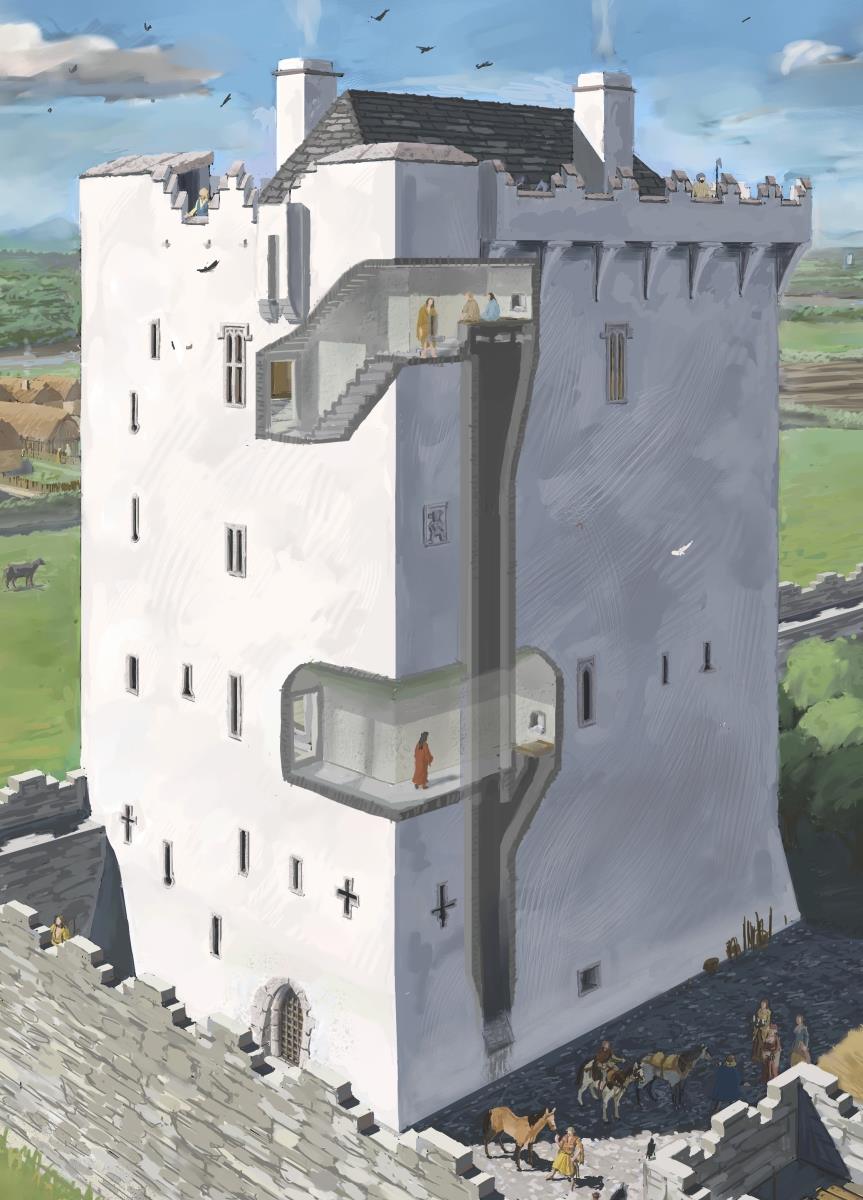

Home of the Taoiseach, or Head of the Clan, Ardintenant was one of the most important of the O’Mahony Castles of Ivaha (or what we now call The Mizen). Fortunately, it is relatively intact and we can observe and record much about it. The drawing above was done by James N Healy for his magnificent book on The Castles of County Cork. This post is another in my series on The Castles of Ivaha.

First the name – Ardintenant has been variously interpreted as coming from Árd an Tine (Ord on Tinneh, Height of the Fire), Árd an tSaighneáin (Ord on Tye-nawn Height of the Flash, or Beacon) or Árd an Tiarna (Ord on Teerna, Height of the High Chief). Any of these would be apt, since tower houses by the sea like this one (viewed from the sea, above) could be used as navigation beacons, possibly with a fire on the battlements. We also know that it was the residence of the head of the O’Mahony Clan, even though it was not the largest or most elaborate of the O’Mahony castles. Locally, it is also known as White Castle, which may refer to the white render that once made it stand out in the landscape (for more on render and castle colours, see the discussion on Kilcoe Castle). The photograph below demonstrates that it was prominent on the landscape and close to, although not right on, the sea.

It now stands in the middle of a working farm, surrounded by stone buildings that are picturesque and notable in their own right.

Ardintenant is typical of castles built during the 15th century by Irish clan chiefs – wealthy and powerful and anxious to assert their claims on land and sea.

Dermot Runtach (the Reliable) succeeded in I400; his life and the lives of his sons spanned the Fifteenth Century. He was celebrated as a ‘truly hospitable man, who never refused to give anything to anyone’ . . . The period of 1400 -1500 was the most peaceful and prosperous period in the history of the clan. The Ivagha peninsula was protected by the sea on three sides and the family became wealthy from the exaction of dues from the continental fishing fleets; trade also enriched them, causing long-standing enmity with the citizens of Cork. Tradition relates that the majority of the O’Mahony tower houses in Ivagha were built by or for the sons of Dermod Runtach. The date of Dermod Runtach’s death is recorded in the Annals of Loch Cé as 1427.

THE TOWER HOUSES OF WEST CORK

MARK WYCLIFFE SAMUEL, 1998

Dermot Runtach’s sons were the castle builders. Conor Cabaicc succeeded his father in 1427 and remained Taoiseach for 46 years, embarking on an ambitious program of construction to provide castles for his sons and brothers, beginning with Ardintenant. He died in 1473, by which time probably all of the castles of Ivaha were built and occupied by various members of his derbfine (extended family). Cabaicc means of the exactions (or forced tributes), although it is possible that Conor was more benignly known as Cabach – meaning talkative. His brother, Fineen, the Táiniste (heir-in-waiting) built Rossbrin Castle, about which Robert has written, and which is the castle in our view at Nead an Iolair. Rossbrin and the remains of a small tower on Castle Island are both visible from Ardintenant.

While there is evidence that other O’Mahony castles were built on pre-existing fortifications such as promontory forts (see Three Castle Head, for example) or ring forts, this is most visible at Ardintenant, where the ring fort can still be seen as a circular rampart around the tower house. You can make out part of it in the photo above. Another unusual feature is the survival of a single flanking tower, along the line of the ring fort and across from the tower house, although there may have been more than one originally, since the 1840s OS map shows what could be a second one – the leftmost building on the line of the ringfort below. Note that farm buildings also dot the site even at this early stage.

The possible second flanking tower had disappeared by the time the next series of maps were produced, around the 1890s. The farm buildings have changed as well.

In his marvellous paper on Ardintenant Castle in Mizen Journal 11, 2003, John Hawkes investigates the history and construction of the castle and provides elevation and plan drawings. I am grateful for his scholarship and thoroughness, which has informed the following description of what is left at this site, as well as provided illustrations.

The presence of the ringfort raises an intriguing prospect since it appears that instead of the usual rectangular bawn, surrounded by a stone wall (see the illustration in this post), we have a round bawn, with the stone wall built on top of the bank of the ringfort. Although that stone wall is not obvious now, it is noted in the description of the ring fort in the National Monuments survey. Thus, what we have here is a hybrid ring fort/tower house – a sensible adaptation of a pre-existing fortification and a continuation of the site as a high-ranking residence. The National Monuments survey also refers to an external fosse, although traces of it are hard to see on the ground. If it was originally a substantial ditch, another possibility is that the bank was surrounded by a moat.

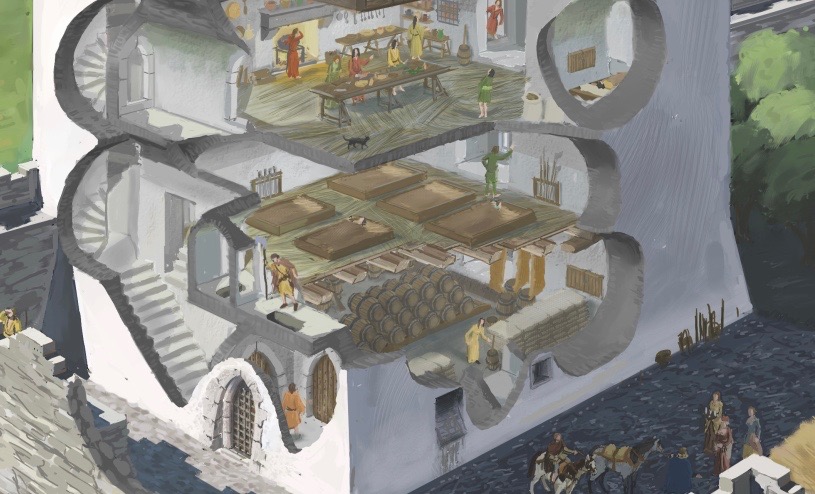

As with all of the O’Mahony Castles, Ardintenant is the type of tower house known as Raised Entry, that is, the ground floor door allows access to the public areas of the castle, while the door above it, originally accessed via a wooden stairway, gives on to a set of steps up to the private area.

The first two-and-a-mezzanine floors are covered by a vault. This set-up was partly defensive – the upper floors could only be accessed through this raised doorway and staircase – and partly for security, in that the vault was a barrier should a fire break out on the lower floors. The doorway to the left leads to a garderobe, while on the right are two deeply splayed window embrasures.

At Ardintenant, as with Dunmanus, the ground floor has been in use as a cow byre. It is normally impossible to access the upper floors, although those who have done so report that it is in good condition. That floor is reached by means of a mural staircase that rises from the raised entry.

A second staircase, in this case a spiral, gives access from the upper floor to the wall walk. This was not a castle built for comfort – in common with the other 15th century O’Mahony castle it had no fireplaces and very few windows.

Above the vault was what Hawkes calls the Great Hall. One large room, accessed via the mural staircase, the only notable feature of which is are deeply splayed window with seats in the embrasure. Picture the Lady of the house seated here, trying to catch whatever light she could as she bent over her handwork.

In one corner of the Great Hall, the spiral staircase led up to the wall walk (what Hawkes calls the Allure). While nothing remains of these battlements now, we can assume that there was a walkway around the roof, perhaps with Irish crenellations and a sentry box.

The flanking tower (above) is covered in ivy, so it’s hard to make out details. It may have looked a bit like the one Westropp called The Turret, at Dunlough.

It’s much smaller than the castle, rectangular, and three stories high. The illustration above, by Jack Roberts, indicates the relative sizes. The way in was from the level of the curtain wall and each floor was connected by a ladder, except for the wall walk/allure, reached by a spiral stone stairs.

Hawkes tells us that “its function appears to have been to accommodate hostages.” He bases that on the absence of a ground level entry (the current hole on the ground level having been broken through in more recent times), so that the ‘dungeon’ was accessed through a trap door from the room above, which in turn he calls a ‘detention room.’ See my post on Dunmanus for a discussion of possible functions for rooms like the ‘dungeon.’

Ardintenant is still standing and intact, but a lot of the base batter – the broad stone base that gives it its strength and stability – is missing and holes have been punched through the walls in the past.

Along with the other extant O’Mahony castles, its continued survival cannot be taken for granted. It’s a listed monument on private land, and Ireland’s complicated heritage laws means that it can’t be deliberately damaged, but conversely, there is no onus on the landowners to conserve it at their own expense. All fingers crossed that it remains standing for ages to come.