This is the last part (links to Parts 1 and 2 at the end of the post) and I will use it to look at where most people seemed to be living – along the River Lee and the Blackwater/Bride Rivers. Cork is shown, as we know it was and still is, on an island, as a substantial walled town with four towers. Two of the towers guard bridges and are ports of entry, and two guard inlets of the river. There’s a cross in the middle and five buildings outside the walls.

The buildings to the left of the city (remember, that’s North) are labelled Mogelle, F:barro and M:nellan, while to the right (south) the upper building is unlabelled and the lower one is C:Tanboy?

To see what this is all about, let’s take a look at the earliest map of Cork City, which I showed you in my post Mapping West Cork, Part 2: John Speed. I reproduce that map here. It dates from 1611/12. As I said in the John Speed post, while Speed seems to have based his land maps on earlier work by Mercator . . .

. . . the city maps were all new and it seems that Speed, with one of his sons, actually travelled to the cities he includes in his atlas and paced out the distances, drawing the maps based on these calculations. They are a unique and invaluable record of a time when Ireland had walled cities, especially given that so few intact stretches of those walls remain.

And there is the Market Cross! While that is the only feature inside the city on our map, Speed’s is beautifully detailed, and he provides a key to all important buildings. There are many churches, only two of which, Christ Church and St Francis’s Church, are within the walls. Assuming that Finbarr’s church is labelled F:barro on our Map (although the brown rectangle looks more like a tower house) and St Barrie’s Church on Speed’s, it is shown in different places. St Augustine’s or St Stephen’s may be the uppermost building to the right of the city, but what is the brown pyramid-shaped blob labelled C:Tanboy? Perhaps a true Cork historian can help us out here and figure out what’s what.

Interestingly, there is no sign, on our map, of the large star-shaped fort that Speed labels The New Fort and that subsequently became known as Elizabeth Fort. It was started in 1601 by George Carew (the original owner of this map collection) built of earth, stone and timber. This supports a pre-1600 date for this map. Elizabeth Fort is still very much part of the Cork landscape, with its massive walls still dominating the south side of the river (above).

As we progress west along the Lee, the land is shown as wooded and there are several establishments by the river and its tributaries. I recognise Kilcrea Castle and Abbey (given here as Kileroye), but I’m sure others, more familiar with this landscape than I am, can add more.

Cork Harbour, as might be expected, has many towers, the main one among them still standing is Barry’s Court (barris courte), soon (we hope) to be re-opened for visitors and also Belvelly (B:vyle), magnificently restored by a private owner. Corkbeg Island and Castle are shown, as well as several other castles on either side of the delta. Cloyne is of course indicated, as it was an important ecclesiastical centre.

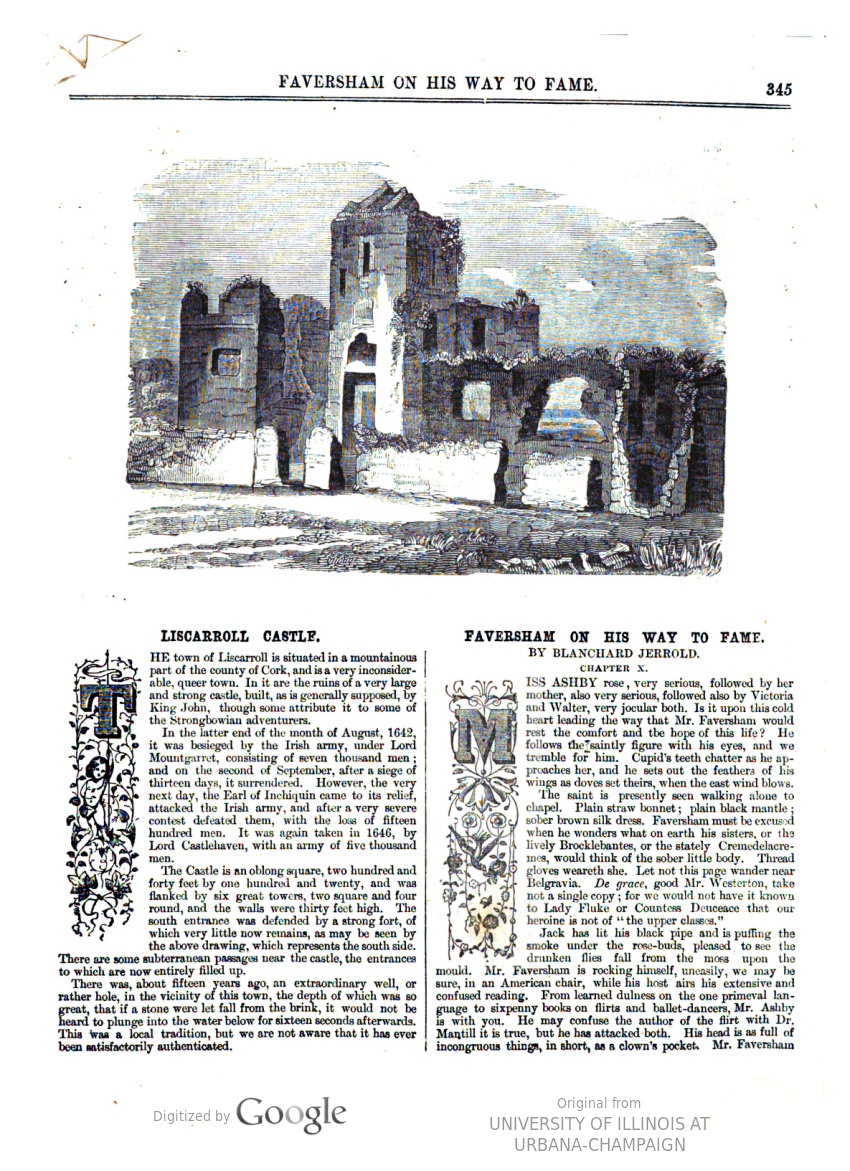

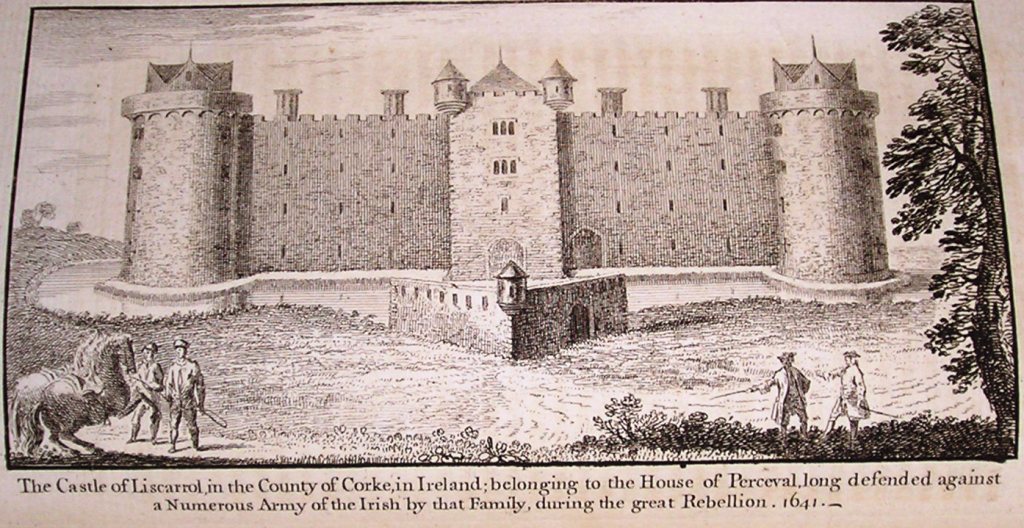

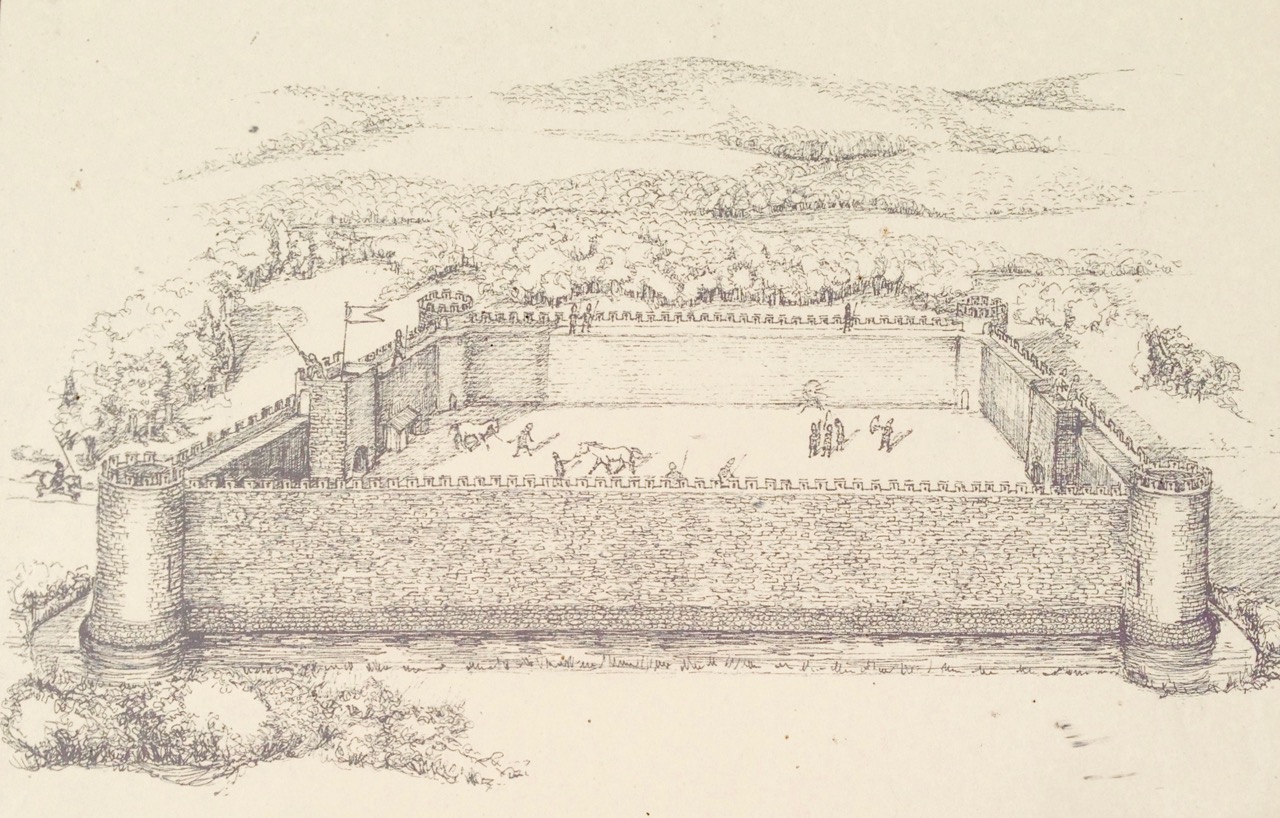

Moving now to the Blackwater/Bride River system, we see perhaps as populous and encastellated an area as around Cork, especially along the two rivers, which were navigable for many miles inland. Youghal is shown as a walled town, guarding the mouth of the harbour but also a large commercial and trading centre.

We have written about Youghal before, and specifically about its well-preserved stretches of wall – an unusual feature of Irish towns as very few medieval walls have survived.

I am reproducing below the map from Pacata Hibernia I used in my Youghal’s Walls post. As with Cork, it can help us to understand a bit more about Youghal. Note, for example, the South Abbey clearly shown outside the walls on both maps.

Upriver is Strancally Castle – not the more modern manor house, but the original tower house of which only a vestige remains down by the river. Also easily discernible is Pilltown in modern-day Waterford and Inchiquin, a townland east of Youghal. Inchiquin Castle is now the ruins of a round Anglo-Norman masonry tower which went through tortuous changes of ownership but was eventually occupied by in the fabled Countess of Desmond who in 1604 died at the age of 140 by falling out of an apple tree. The castle was then seized by Richard Boyle, Great Earl of Cork, who, along with Walter Raleigh, is closely associated with Youghal and the Blackwater River. The drawing of Inchiquin below is by James Healy from his marvellous book The Castles of County Cork.

Boyle’s Castle (it’s still there) was in Lismore, but at this point lesse more is shown as a church on the banks of the Blackwater, not the centre of power it became with Boyle’s ascendance.

Castles, towns and churches line the Bride and the Blackwater, showing how important these rivers were at a time when the best way to traverse the country was by water.

I’m going to leave it there, although I just might come back to this map at some point in the future because, well, it’s so darn interesting and it’s fun to try and puzzle out the names. I hope I have supported my thesis that this map must date to before 1600. It is most likely another of those made for the purposes of identifying property in order to confiscate and carve it up during the Plantation of Munster. Please do visit it for yourself and see what you can find – additions always welcome in the comments section below.

OK – one last image – the source of the Blackwater is shown in this one. What do we call these mountains now?