In 1539 a certain Heneas MacNichaill (Henry McNicol) of Armagh confessed to a particularly heinous crime, that of strangling his son. We know nothing about the reason, nothing about the son – an indication that it was more important to record the punishment than the details of the crime.

We know what the punishment was because it is recorded in the Register of Bishop George Dowdall. Dowdall was a fascinating character, living in a time when it was prudent to be Catholic, then Protestant, then Catholic again and finally back to Protestant. Dowdall was not for turning – he resigned his seat as Primate of Ireland rather than approve of the Book of Common Prayer. He was later restored to the See by Bloody Mary (below), dying conveniently just before she did. While in office he kept what is known as ‘Dowdall’s Register’, the last in the series of volumes of medieval records which survive for Armagh.

One of Dowdall’s Deans, Edmund, meted out the punishment to Heneas MacNichaill. He was ordered to do a round of pilgrimages to all of the great Irish Medieval Pilgrim sites – 18 of them. We don’t know how common such a sentence was, but Salvador Ryan tells us that such punishments

. . . often took the form of a long, arduous pilgrimage, a substantial deed of almsgiving or some kind of penitential abstinence or fasting.

The annalists frequently record instances of pilgrimages undertaken as penance. The Annals of Ulster, for instance, relate that in 1491 ‘Henry, son of Hubert, son of James Dillon slew his own father, namely Hubert, with thrust of knife and he himself set out for Rome after that. The sinner might also found a monastery, as expiation for sin, or at least offer to sponsor an existing foundation’s restoration. Some accounts of the Mag Uidhir clan illustrate how individuals belonging to an important Gaelic family, in this case rulers of Fermanagh, made reparation to their God. In 1428, ‘Aedh, son of Philip Mag Uidhir went on his pilgrimage to the city of St James…and died…after cleansing of his sins in the city of St James.’

St James, above, with his pilgrim’s attributes of the scallop shell and the staff and pouch.

Heneas returned two years later, in 1541. The Register records it thus:

71. Certificate of fulfilment of penance. Memorandum that, on the 4th April, 1541, Heneas McNichaill, a layman of Armagh, appeared before the Primate to declare that he had fulfilled the penance imposed on him by Edmund, Dean of Armagh and custos of the spiritualities of the vacant see, for having strangled his son.

He had visited :

1. Struhmolyn in Reghterlaegen in Patria Kewan (or Rewan ?).

2. Lectum Cayn in Glendalough (i.e., St. Kevin’s Bed).

3. Rosse Hyllery 0 Garbre in patria McCarbre Rewa, principale purgatorium hic ut dicit (Ros-ailithreach, Co. Cork).

4. S heilig Meghyll in patria McCathiremore (i.e., The Skelligs, off the coast of Kerry).

5. Arayn Nenaw (i.e., Ara na Naomh).

6. Cruake Brenan in patria militis Kerray (Crock Brendain, in Kerry).

7. Sanctorum Flanani et McEdeaga in Momonia (i.e., Killaloe).

8. Comllum. Sti. Patricii in Conacia in patria Y maille (i.e., Croagh Patrick).

9. Purgatorium Sti. Patricii apud Loughdirge in patria Ydonyll (i.e., St. Patrick’s Purgatory in Lough Derg).

10. Enysskworym Sti. Gworain Anmerrys Downy

11 in Conacia (Gort, Co. Galway). 11. Cornancreigh in patria McSwyne.

12. Tyrebane in patria Ydonyll.

13. Sanctum Cntcem apud Woghterlawan in patria Comit?s Ormond (i.e., Holy cross).

14. Can eh C ai s sill (i.e., The Rock of Cashel).

15. Dwyne, et Sawyll, et Craen Yssa (or Craev Yssa) et Strwyll (i.e., Down, Saul . . . and Struell).

The Primate re-affirmed the absolution. (Primas continuavit causam absolu tio

Laurence P Murray*

So Heneas had done his time and was forgiven his great sin. But where had he gone on this trip around Ireland? The sites have all been identified by scholars. Some are obvious (Cashel, Lough Derg, Croagh Patrick, Glendalough) and remain important sites of pilgrimage to this day.

But some are obscure – and it’s one of those I want to talk about today. Number 7 on the list is recorded as Sanctorum Flanani et McEdeaga in Momonia. Sanctorum Flanani is straightforward – it’s St Flannan’s Shrine in Killaloe (below).

It’s the one next to it that had scholars chewing their pencils – McEdeaga in Momonia. But it has now been identified as St Erc’s Holy Well in Glenderry, near Ballyheigue, on Kerry Head in the extreme northwest corner of Kerry. Amanda had tried to find it twice before but last week she hit it lucky and I was along for the ride.

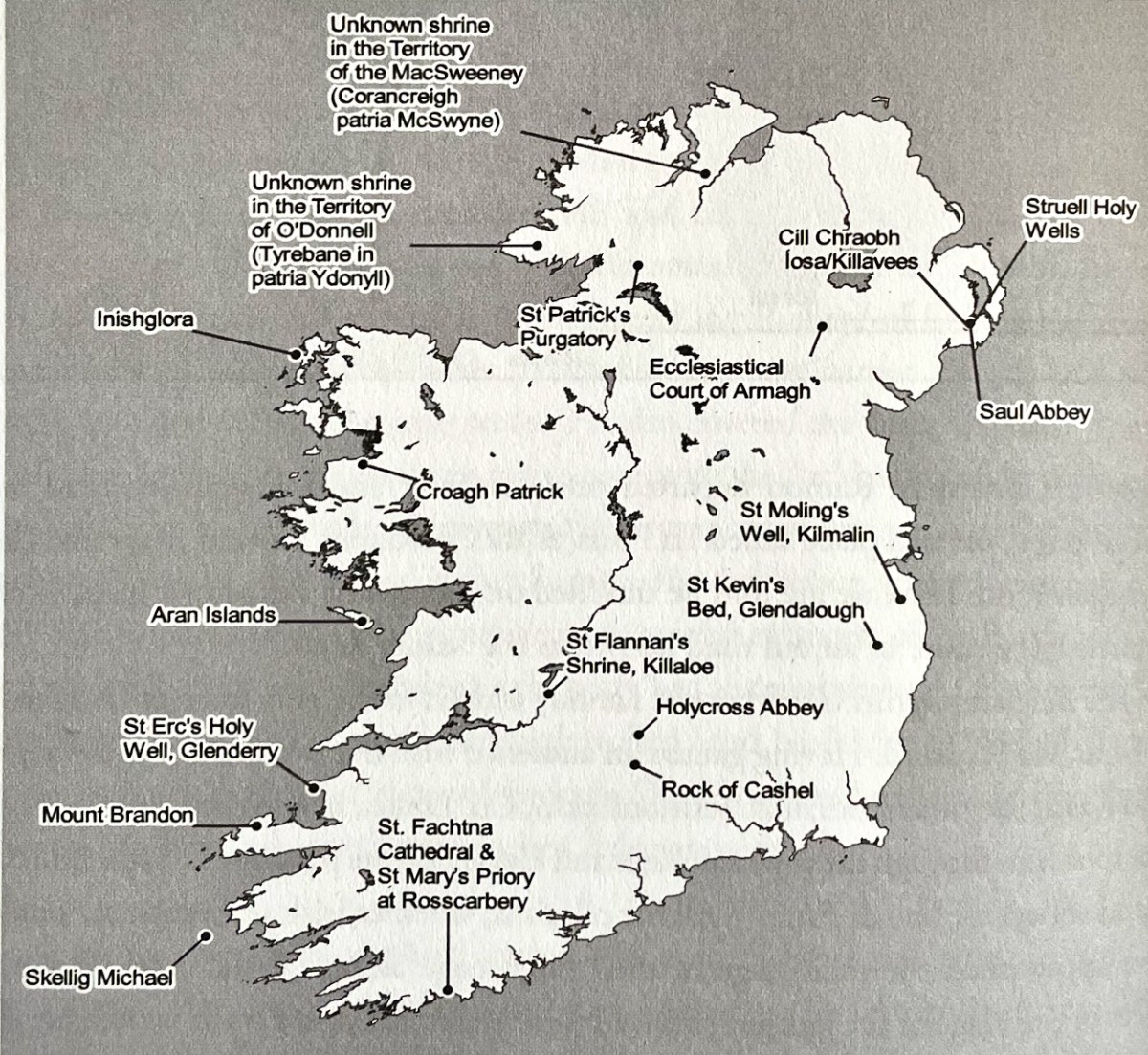

This map is from the wonderful Journeys of Faith: Stories of Pilgrimages from Medieval Ireland by Louise Nugent. One of our reasons for being in Kerry was to hear Louise’s talk to the Kerry Archaeological and Historical Society and she showed us this illustration of Heneas’s journey – I was immediately captivated by the fact that the well Amanda was seeking was on the map!

I can’t emphasise enough how obscure this well is now. Although the Corridons, the traditional well-keepers have kept the knowledge alive, it has faded from the memory of everyone else and is no longer a site of pilgrimage at all. And who was St Erc? His little church, above, is still a sacred spot on Kerry head. He is associated with St Brendan – he baptised Brendan and blessed his voyage.

I will treasure forever Amanda’s excitement at Michael Corridon’s offer to take her to the well, and the enormous beam on her face upon her return. But there was one more thrill in store – so what I want you to do now is go to Amanda’s blog and she will take up the story. This is a co-op blog!

I will leave you with Michael Corridon and Amanda setting off for the well. Now go to A Mysterious Well at the End of the World – St Erc, Kerry Head