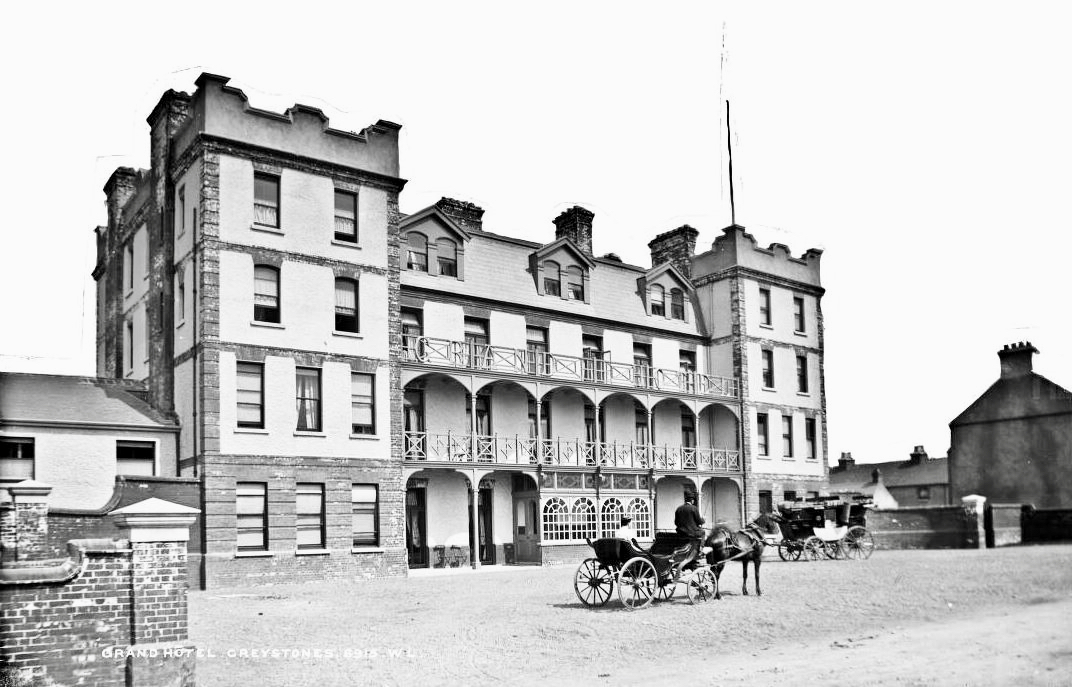

Above – Trafalgar Road, leading down to the harbour, Greystones, c1900. This seaside town is in Co Wicklow, and the connection with West Cork is that our ‘Big Fella’ – Michael Collins – had intended to set up home there once he had married Catherine (Kitty) Kiernan. Collins was staying in the Grand Hotel when he proposed to Kitty. That building is better known to us as the La Touche (photo below from the National Library of Ireland).

Above: la Touche, mid 20th century. Today, the hotel has been transformed into modern apartments (below). The fine original central building has been retained and upgraded:

Michael Collins and Kitty Kiernan have been described as ‘star-crossed lovers’. The pair were first introduced by Michael’s cousin, Gearoid O’Sullivan, who was friendly at the time with Kathy’s sister, Maud. Kitty was also close to Harry Boland, who served as President of the Irish Republican Brotherhood from 1919 to 1920. Boland was a good friend of Collins.

Harry Boland (left), Michael Collins (centre) and Éamon de Valera (NLI public domain c1920). Collins and Kiernan announced their engagement in 1921 and planned to marry the following year, but the political upheavals of the time kept delaying the wedding. During this turbulent period, Collins had ‘grown quite fond of Greystones’, often spending time in the house of his aunt, Maisie O’Brien Twohig – Dysart, Kimberly Road. Ironically, this property backed on to the RIC station.

(Upper) Dysart – home of Michael Collins’ Aunt Maisie. (Lower) former RIC barracks and present-day Garda station, immediately adjacent to Dysart.

(Above) Kitty Kiernan. Collins and Kitty had planned to live in Brooklands, on Trafalgar Road, Greystones (below), after their marriage.

Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith and Robert Barton were delegates to the Treaty Negotiations that ended the Irish War of Independence in December 1921. Before he left Greystones, it is recorded that Collins visited Fr Ignatius of the Congregation of the Passion:

. . . The facts are these: he [Collins] was staying at the Grand Hotel, Greystones, while I was giving a mission there. It was coming near the close of the Mission. Michael was very busy in Dublin, worked and worried almost beyond endurance. He got to Greystones one night very late and very tired. It was the eve of his departure to London, re the Pact. He got up the next morning as early as 5.30 am and came to the Church, and made a glorious General Confession and received Holy Communion. He said to me after Confession, “Say the Mass for Ireland, and God bless you, Father”. He crossed an hour or so later to London . . .

Patrick J Doyle PP, BMH.WS0807, pp 39-40, 90-91

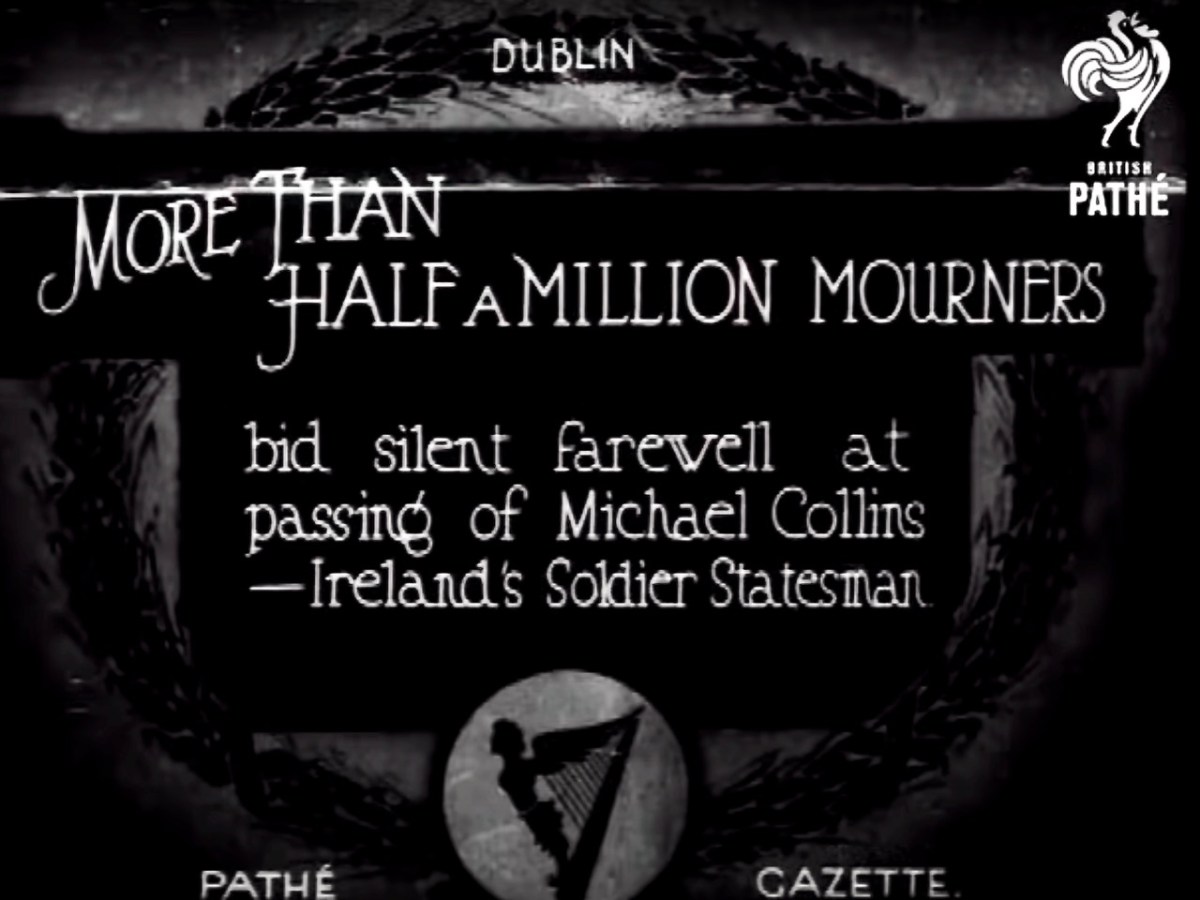

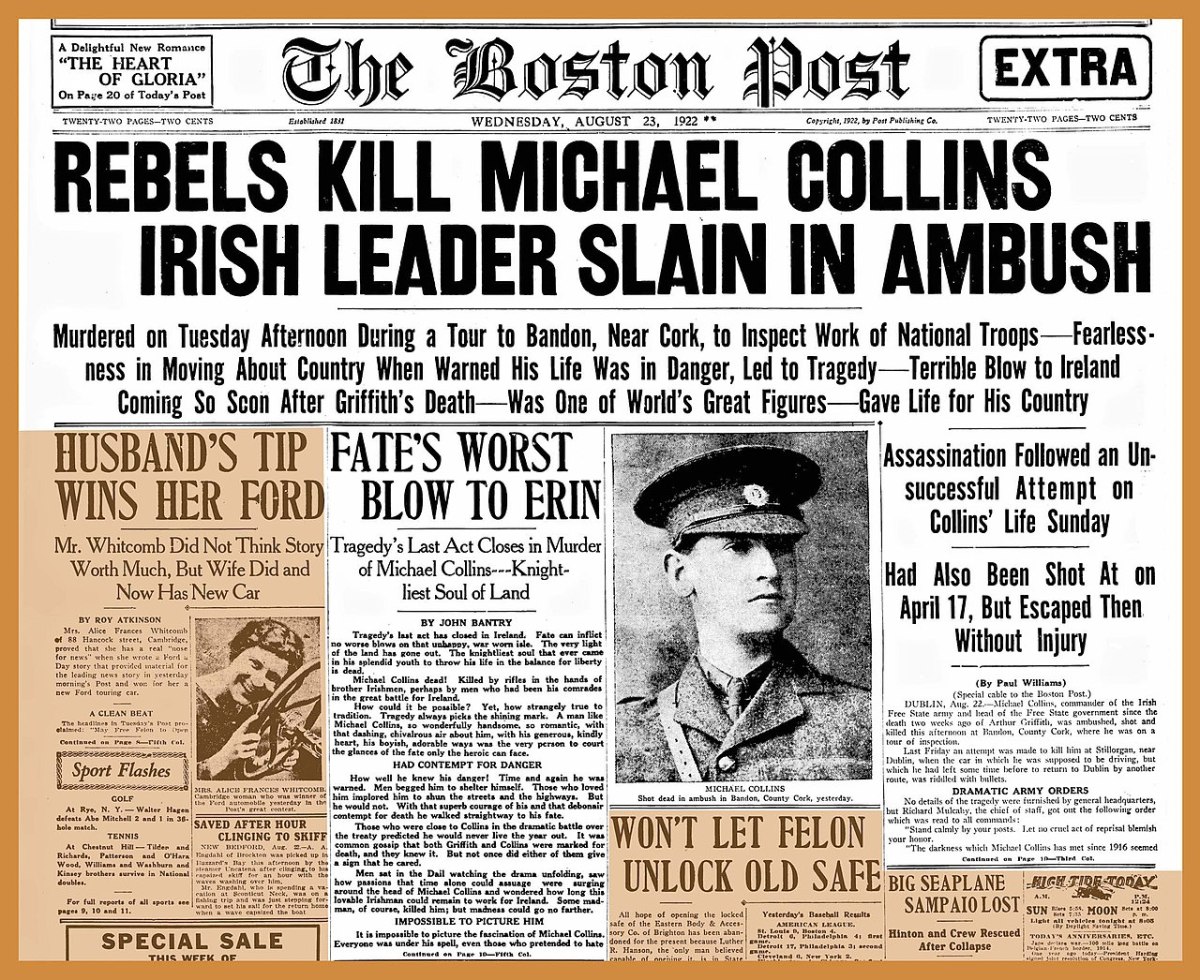

(Above) St Brigid’s Church, Greystones. Fatefully, Collins was shot in West Cork on 22 August 1922. Collins “. . . One of the World’s greatest figures . . . Knightliest Soul of the Land . . .” was mourned by the nation, and – of course – by Kitty.

(Above) headlines in the Boston Post on the morning of 23 August 1922.

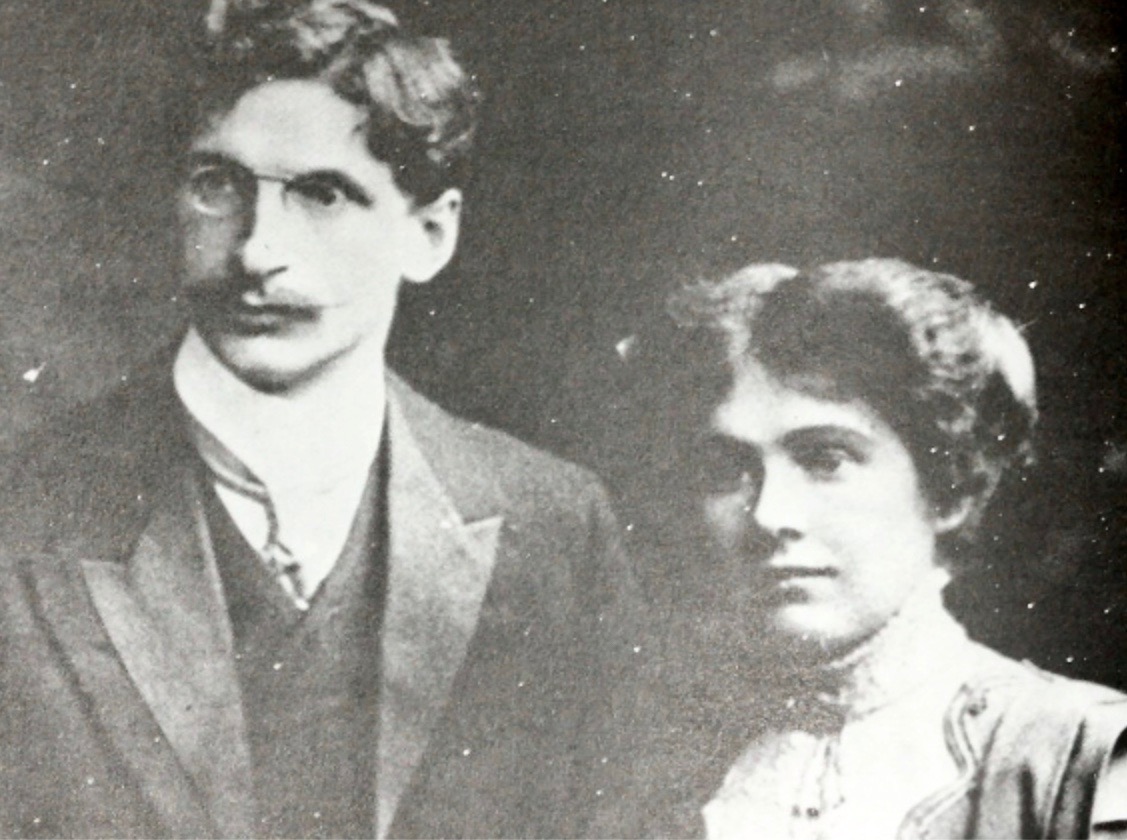

The de Valeras – Éamon and Sinéad (above, in 1910) – took a house in Greystones soon after the 1916 rising, situated on Kinlen Road in the Burnaby Estate. The house was built at the turn of the 20th century by Patrick Joseph (PJ) Kinlen, who lived there for a time himself. PJ built much of the Burnaby estate and Kinlen Road was named after him. They named the house Craigliath – it is now known as Edenmore (below).

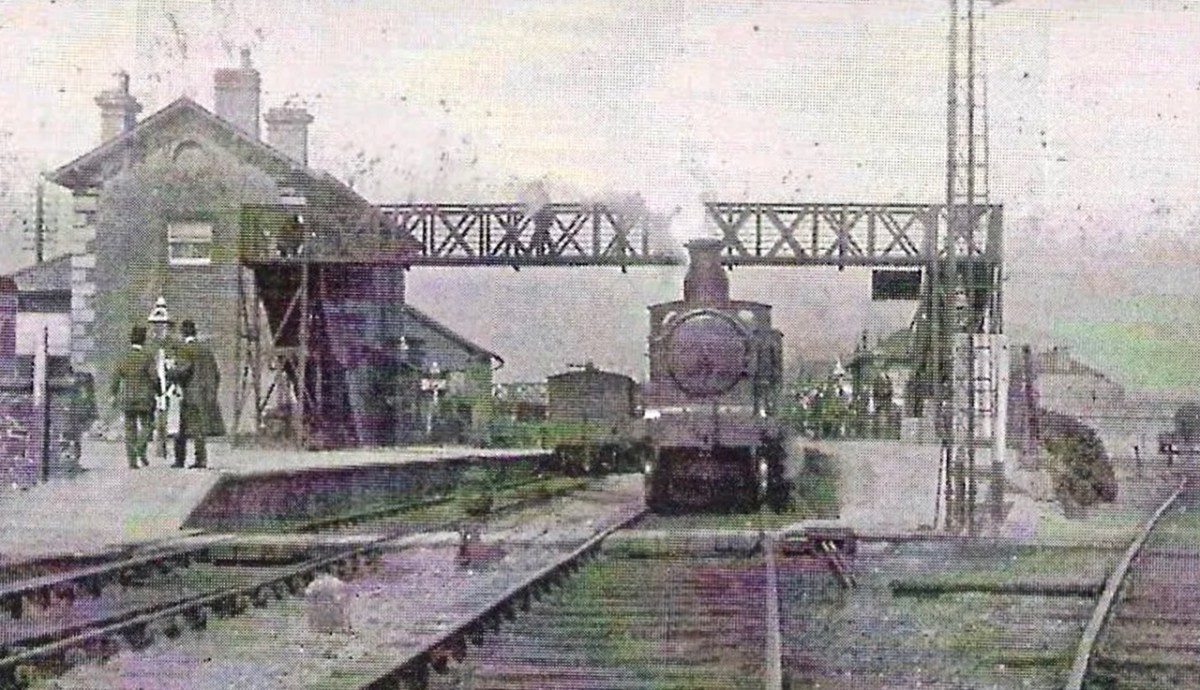

A reason for the popularity of Greystones in the early 20th century was its relative proximity to the centre of Dublin, and the railway line which gave access to the city. If any readers have travelled on this line – which goes down the east coast as far as Wexford – you will know that the section between Bray and Greystones is one of the most adventurous railway journeys in the world! Engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, it clings to the precipitous cliffs and ran on trestle-bridges and through a series of tunnels: there have been many incidents during its history, and the line has had to be reconstructed a few times to avoid the effects of erosion. (With thanks to the Greystones Guide for the image below):

A popular story tells how Éamon de Valera was travelling home from Harcourt Street to Greystones on the night of 17 May 1918. When the train reached Bray, the driver saw that “two detectives” (although some versions say it was a number of constables) had boarded the train a few carriages behind.

. . . [The driver] felt sure that the intention was to arrest de Valera that night in Greystones. He said that they would slow down the train coming into Greystones before they arrived at the station at a certain point, which they indicated to de Valera, and they advised him to jump out of the carriage on the off-side, and that he could easily get away, and afterwards they would put on speed . . .

However, de Valera chose not to accept this offer, and when the train arrived at Greystones, he was apprehended and arrested. The Irish Independent adds a few further details:

. . . Dev “. . . was taken to the waiting room under a heavy guard, and after being searched, was placed in a motor car and driven to Kingstown, where he was handed over to the military and placed on board the transport … for England” . . .

Irish Independent, 20 May 1918

(Above: Greystones Station – late 19h Century). Personally, I am unsurprised that de Valera did not accept the train driver’s offer. Jumping from a moving train is not a recommended course of action – especially when the terrain of that section of railway-line is so hazardous. De Valera was imprisoned in England but escaped and then went to America: his wife did not see him for three years. During this time Michael Collins visited her often in Greystones to bring her news and also to provide funds. Later she reportedly told her husband that she was ‘quite in love with Collins’. He grumpily responded: “…That’ll do. There are enough people in love with Michael Collins…” (Below – lantern slide of Greystones Harbour, 1900):

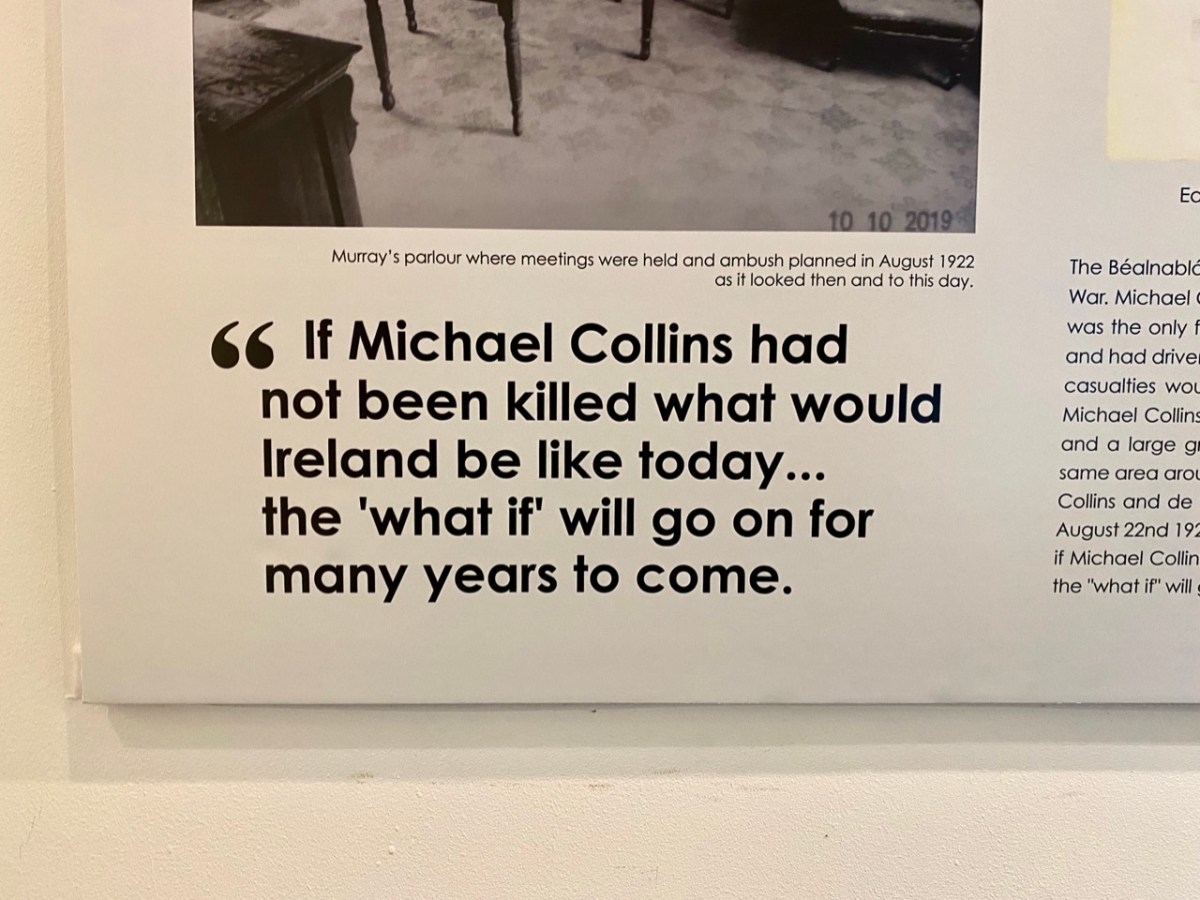

Of course, de Valera lived to tell his tale – he died on 29 August 1975, aged 92, having achieved the status of Taoiseach and President of Ireland – whereas Michael Collins did not: he was shot at Béal na Bláth, County Cork, at the age of 31. It is fair to say that he undoubtedly achieved the perhaps more fulfilling status of National Hero.

Greystones Harbour in 1911. With many thanks to the excellent Greystones Guide for invaluable free access to pictures and information.