Yeats country – Benbulben and Classiebawn Castle (above). Finola took this fine view seven years ago, when we set out to visit the haunts of William Butler Yeats. We have to turn to Yeats now, as it’s exactly one hundred years since he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature – in December, 1923. I have carried a place in my heart for Yeats, ever since I was at Primary School on the Hampshire/Surrey borders, not far from Thomas Hardy’s Wessex. Yeats and Hardy were rivals for the coveted award – the final vote in 1923 was between the two of them: in the end, only two Nobel committee members voted for Hardy, and Yeats achieved the prize. The Guardian newspaper said that “…Mr Yeats is to be congratulated, almost without reserve, on lifting this substantial stake. He is a poet of real greatness; prose, too, he can write like an angel…”, however then arguing that Thomas Hardy would have been a worthier recipient of the award!

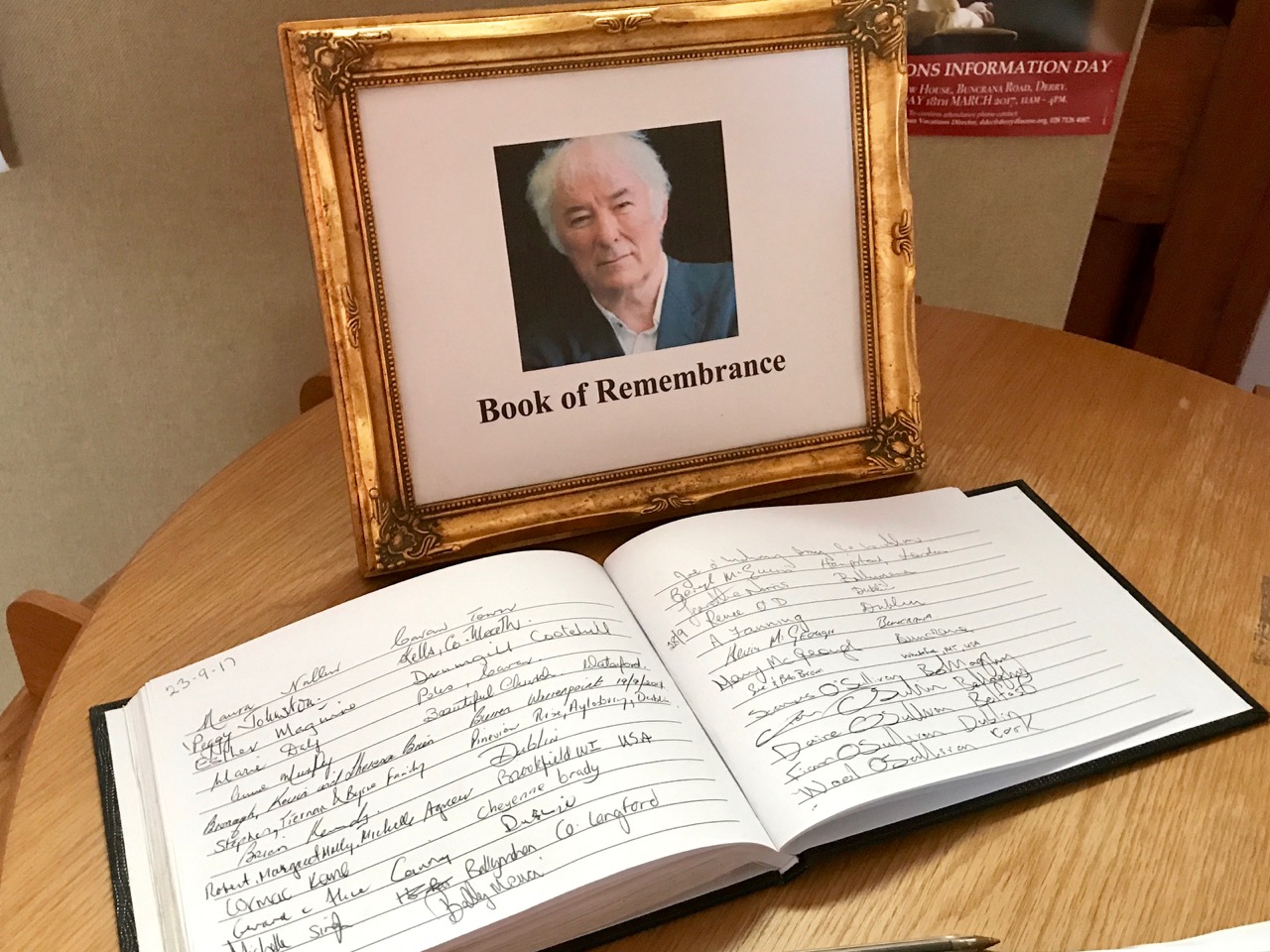

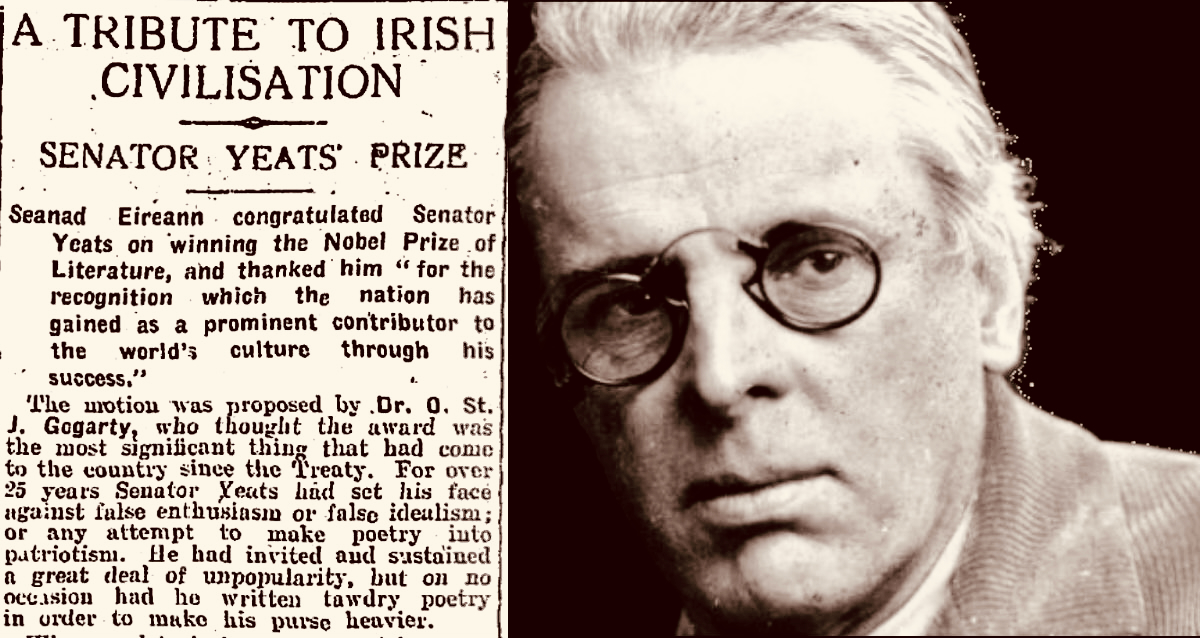

The Irish press congratulates Yeats on his achievement (above – Irish Independent 29.11.1923). My schoolboy encounter with the poet must have been when I was around ten years old and we were tasked to learn The Lake Isle of Inisfree. I can still recite it, word for word, to this day, sixty seven years later. But it was far more than mere words for me, then. Our teacher – Mr Sharpe – was careful to explain that this man was cooped up in the city of London – on its “pavements grey” and was yearning for the countryside he loved:

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

Inisfree serves the poet’s romantic dreams of a remote idyllic landscape far away from the noisy metropolis. It does exist as a place – on Lough Gill in Co Sligo: Yeats spent childhood summers nearby. Interestingly, I searched the internet for pics of the island, and the above came up. It’s from a Roaringwater Journal Post which I wrote in 2016. And it’s not Inisfree, but another ‘lake island’ – just outside Skibbereen, in West Cork – Cloghan Castle Island on Lough Hyne: there’s a holy well nearby, and an 8th century church dedicated to St Brigid – but all that is another story. The diversion just serves to warn against trusting what you find online!

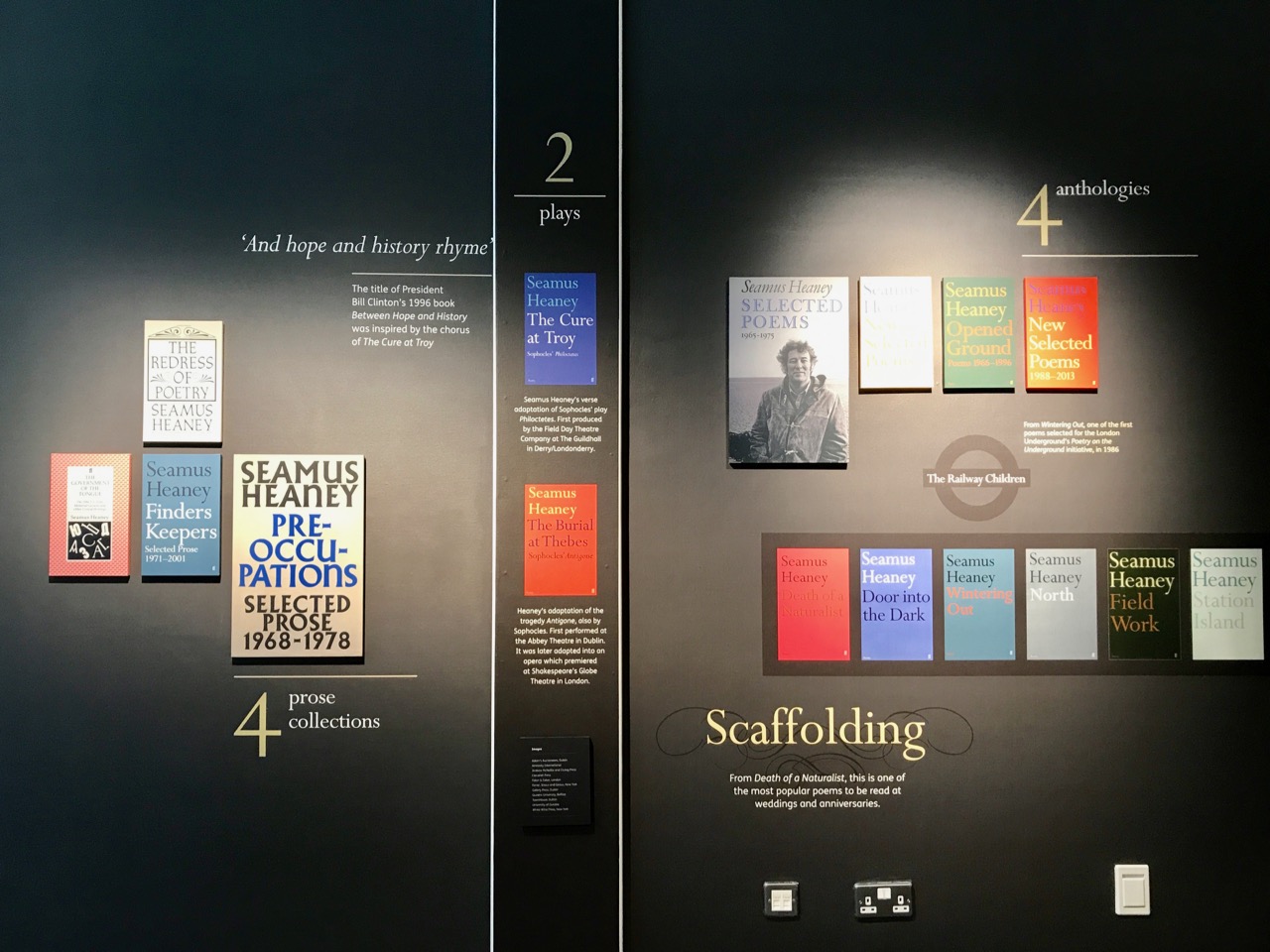

Thoor Ballylee Tower, Co Galway (above) – this 14th century tower house was described by Seamus Heaney, another Irish Nobel Literature prize winner, as The most important building in Ireland, because of its associations with Yeats, who spent many summers there with his family.

Here is the finely crafted cover of The Tower: a book of poems by W B Yeats, published in 1928 (courtesy Yeats Thoor Ballylee Society). The Tower was Yeats’s first major collection as Nobel Laureate after receiving the Nobel Prize in 1923. It is considered to be one of the poet’s most influential volumes and was well received by the public. (Below) a 1917 drawing by Robert Gregory – son of Isabella Augusta (Lady) Gregory and Sir William Gregory of Coole Park, Co Galway – of The Tower (courtesy Yeats Thoor Ballylee Society).

Going back to my early school years: I was an incurable romantic, and a daydreamer. I paid enough attention to lessons to get by, but my heart lay outside the school gates. Just minutes away were hop-fields and, beyond those, pastures, woodlands, streams – idyllic places where I loved to wander. I could completely relate to Yeat’s desire to be far away from the city, and that’s why his poem appealed to me. I knew very little about Ireland, and had no idea that was where I would one day make my home. I am here now, sitting at my desk, with the hills and oceans of Yeats’ own country beyond.

W B Yeats and his wife George Hyde-Lees heard the news that the Nobel Prize had been awarded to him on 14 November, 1923. The photograph above (courtesy Irish Independent) is said to be taken on that day. It’s also said that they celebrated by cooking sausages! The Irish Independent records: “Irish poet and senator, William Butler Yeats created history when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first Irish citizen to achieve such an accolade. The prize was awarded to Yeats ‘for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation’.”

Somewhat surprised by the award, Yeats would later write in his (unpublished) autobiography: “Early in November (1923) a journalist called to show me a printed paragraph saying that the Nobel Prize would probably be conferred upon Herr Mann, the distinguished novelist, or upon myself, I did not know that the Swedish Academy had ever heard my name.” The news of the award was widely praised in Ireland with members of Dáil Éireann proudly announcing that it had placed Ireland on the international stage. It was a sentiment reiterated by the laureate himself, who at the awards ceremony claimed that the Nobel Prize was less for himself than for his country and called it Europe’s welcome to the Free State. In his presentation speech, Per Hallstrom, then chairman of the academy’s Nobel Committee, praised the poet’s ability to ‘follow the spirit that early appointed him the interpreter of his country, a country that had long waited for someone to bestow on it a voice’.

A portrait of Yeats painted by Augustus John OM RA in 1930 (courtesy Sothebys – private collection). Before Yeats passed away he requested that his final resting place be in Sligo. He died in Menton, France in 1939 aged 73 and was buried there. His wish was fulfilled in 1948 when his body was exhumed and buried in St Columba’s Church, Drumcliff. His headstone reads: