This is the post that Robert was working on before he died. I have finished and edited it, keeping it in his voice to the best of my abilities. Finola

Ireland is rightly celebrated for its books – and their talented authors. You will find a thriving bookshop in many a modest Irish town. We are a nation of readers, it seems, and even when we are not reading much, we are buying books and loving books and gifting books, and all the time developing our teetering pile of bedside books to dip into before sleep.

But it takes more than a good bookshop or two to deserve the title of a Book Town. According to the criteria, a town has to have ‘several’ books shops, and particularly shops that sell antiquarian and second-hand books. The only one we have been familiar with hitherto is in Sidney, BC, Canada, where Finola has spent many happy hours browsing among the treasures.

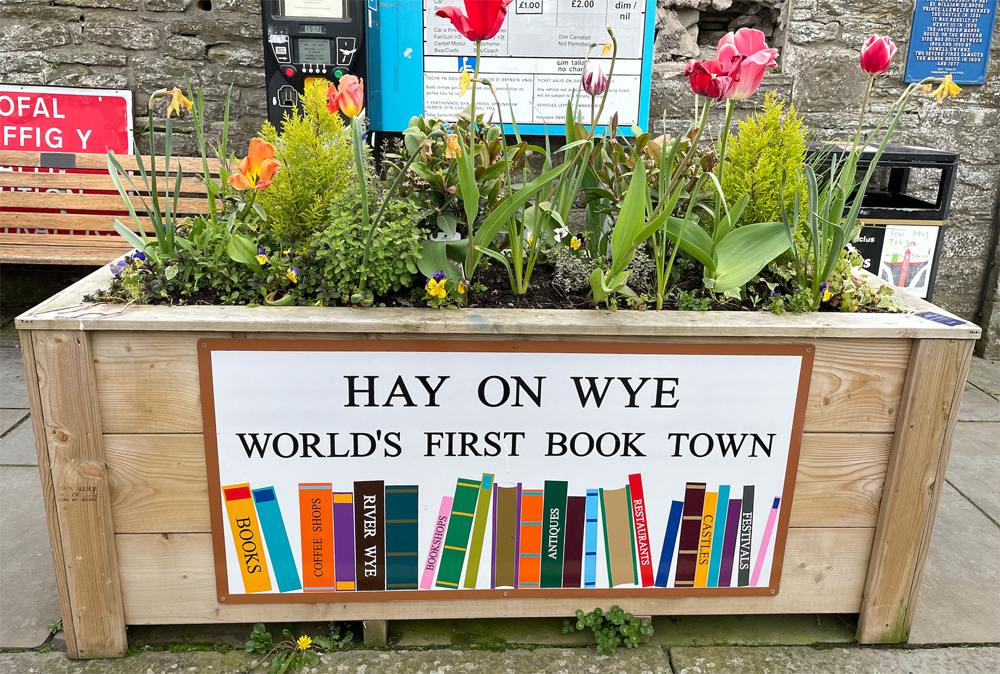

The Book Town model got its start in Haye-on-Wye in Wales (Image courtesy of the Curious Rambler) way back in the 60s and included, from the beginning, the idea that empty heritage buildings should be filled – with books! If you can add events – a festival, readings – or complementary business such as publishers or letterpress printers, all the better.

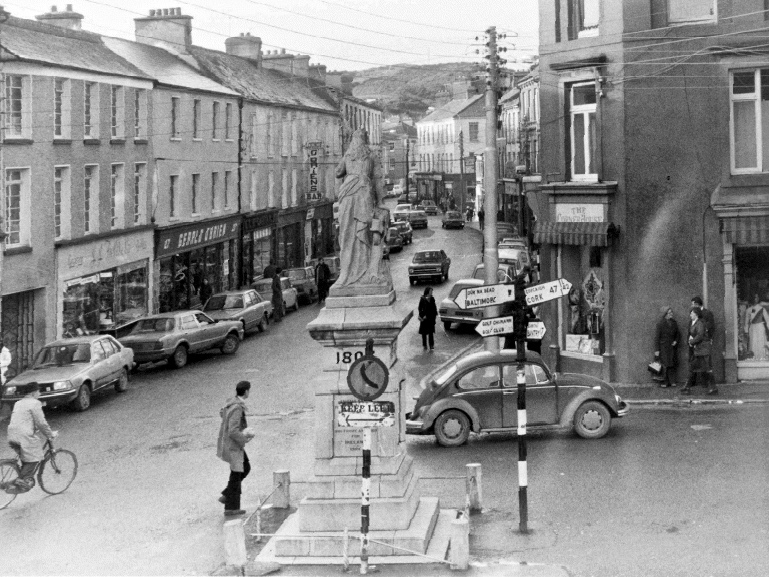

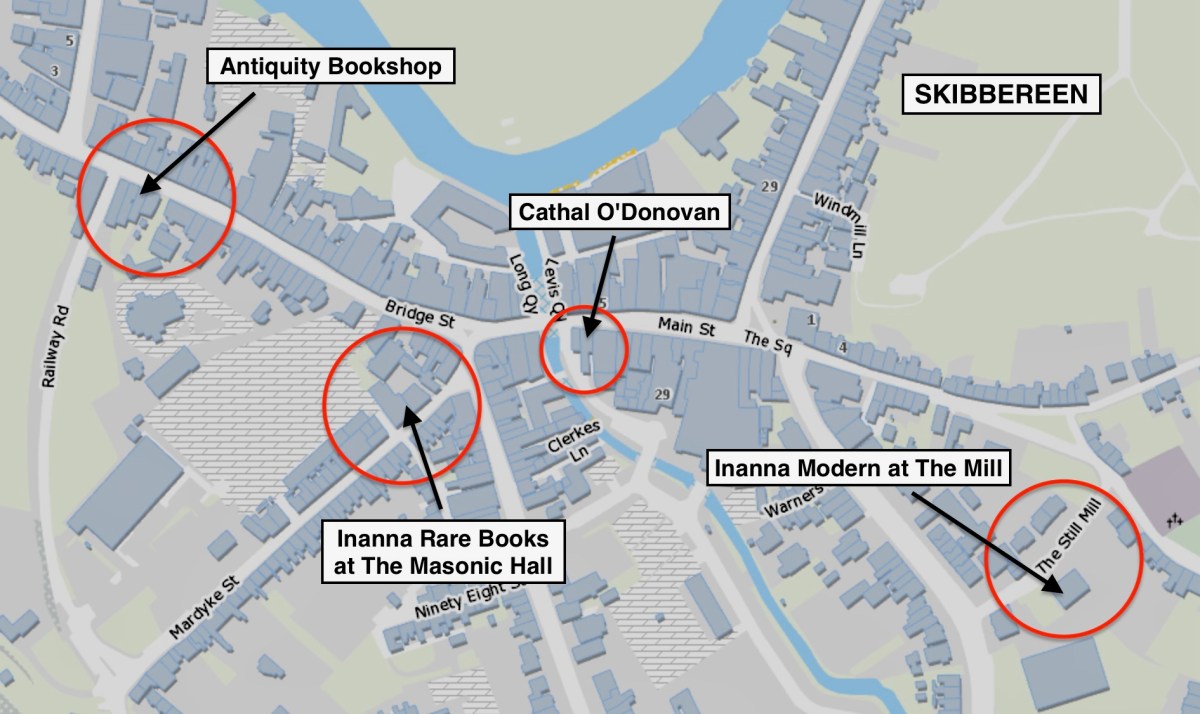

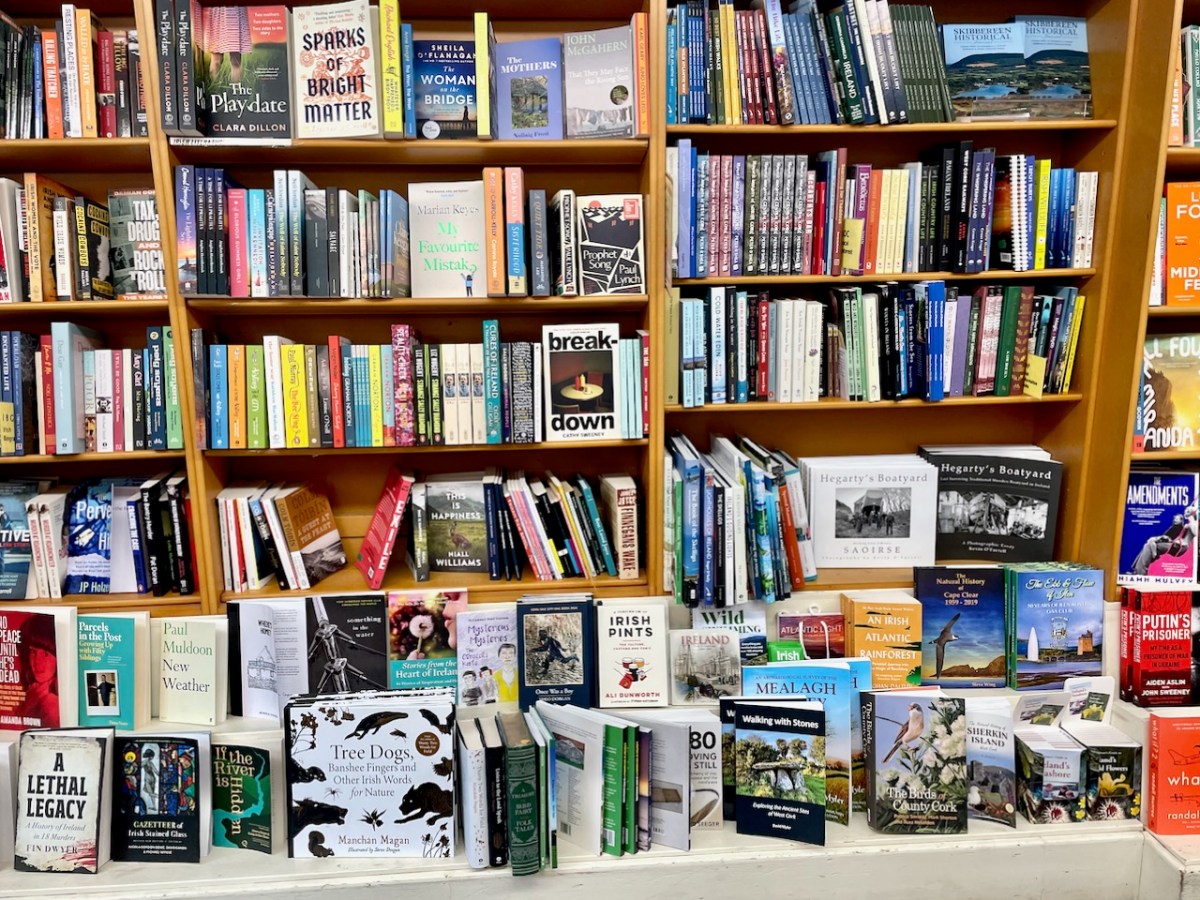

Skibbereen is well on its way to becoming a Book Town, mostly due to the efforts of Holger and Nicola Smyth and their family. Before we get to the Smyths, though, we have to talk about the other books stores and especially Cathal Ó’Donnabháin’s excellent store which supplies us with the best in local interest and contemporary books. In the photo below, taken this week, Finola and I are represented in three of the publications on the shelves. Can you spot which ones?

There’s usually an excellent selection of old books at the Charles Vivian stall at the Skibbereen market on Saturdays – they have a premises too, near Rosscarbery. Even our local SuperValu, Fields of Skibbereen, has done a major renovation and now incorporates a section selling books and periodicals.

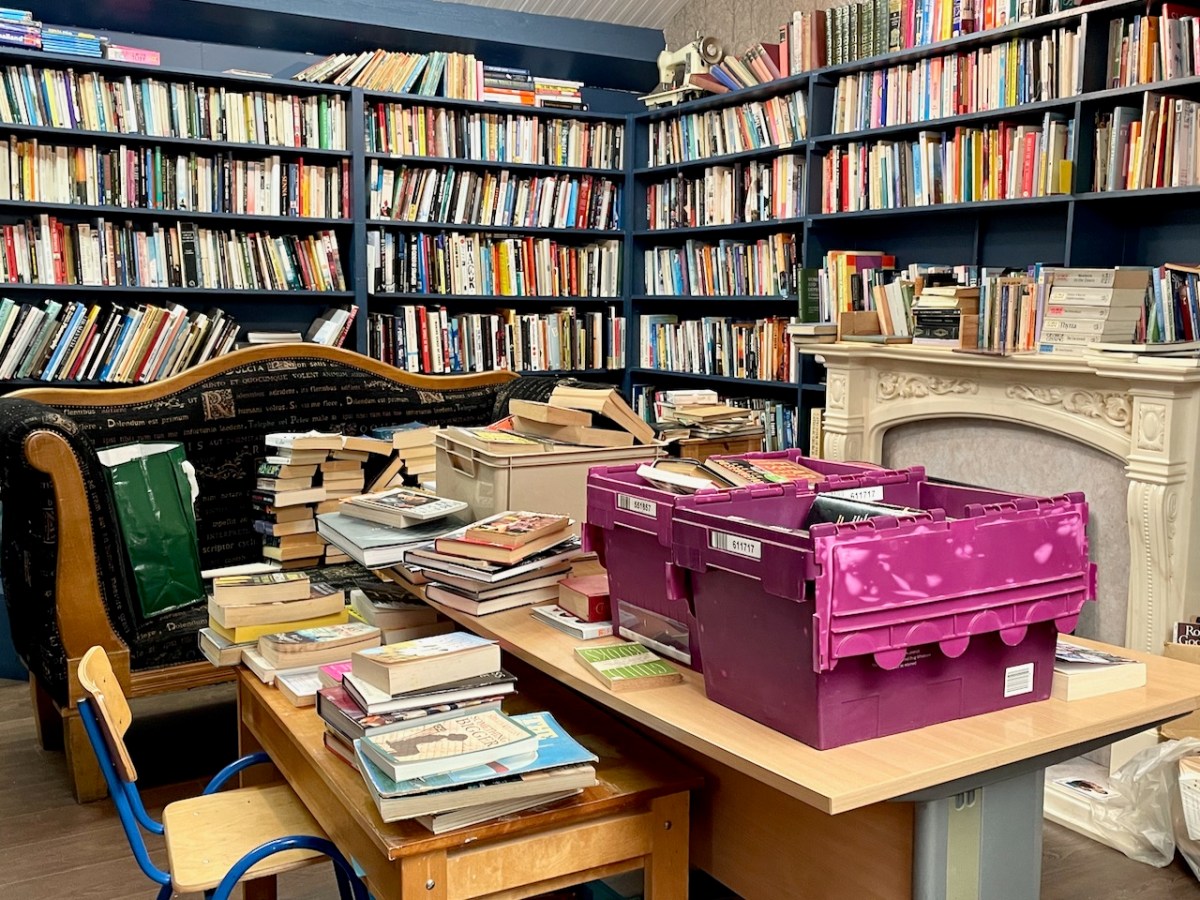

You can spot surprising finds, too, among the second-hand book sections of the town’s charity shops – I was tempted to curl up and spend an hour at this room at the Charity Shop for the wonderful Lisheens House.

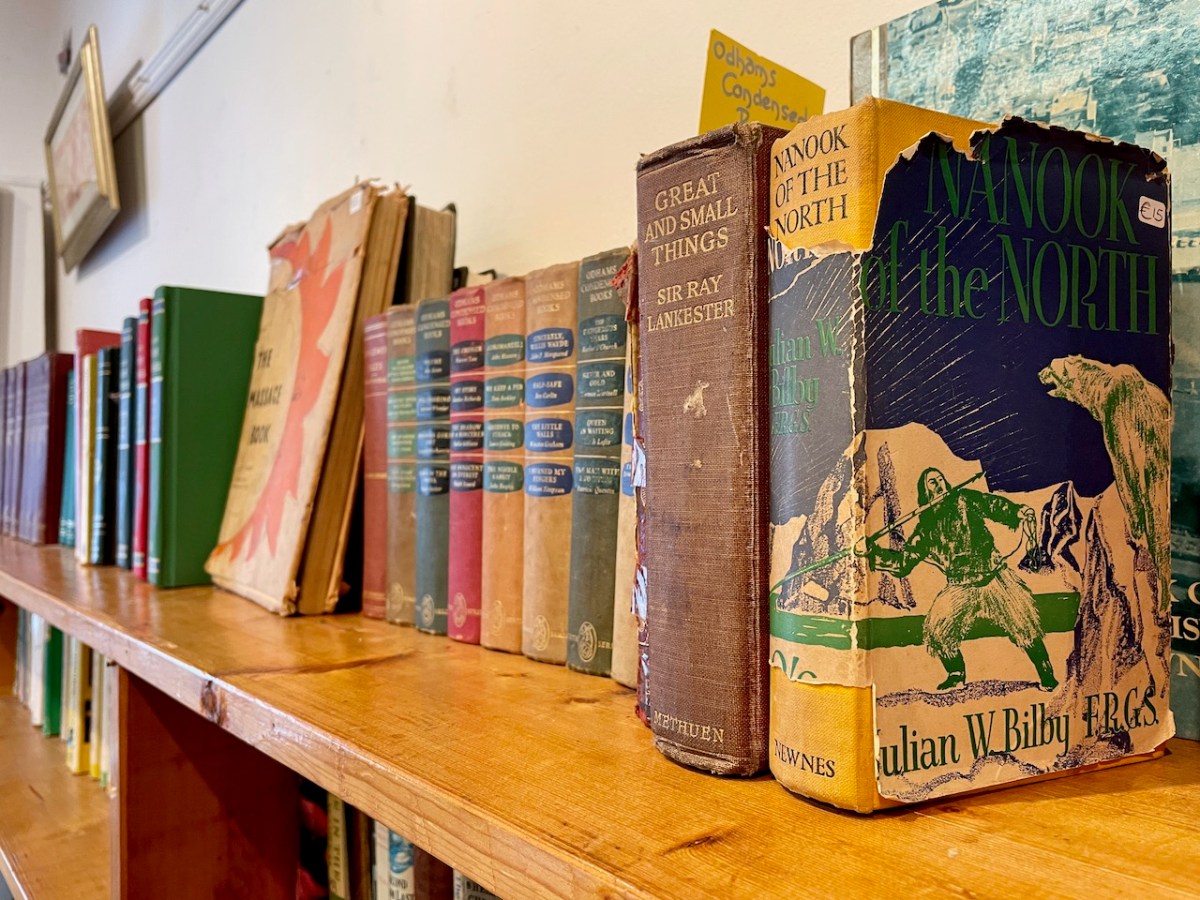

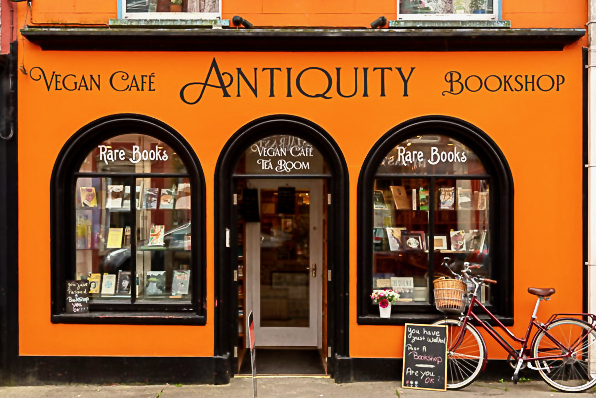

But Skibbereen is also fortunate to be a significant centre for rare and antiquarian books – and much more. What is now known as Antiquity (and might be more familiar to many as The Time Traveller’s Bookshop) is a great asset to all residents in the area. Not only is it “…the first All Vegan Cafe in West Cork…” but it offers a plant-based menu, a juice bar and good coffee – all to be enjoyed in the environment of well stocked shelves of fascinating secondhand books which can be browsed at leisure, and purchased. I can vouch for the excellence of the vegetarian stew!

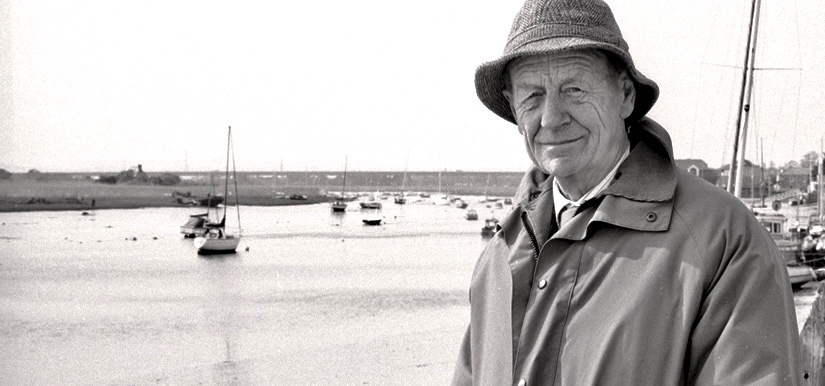

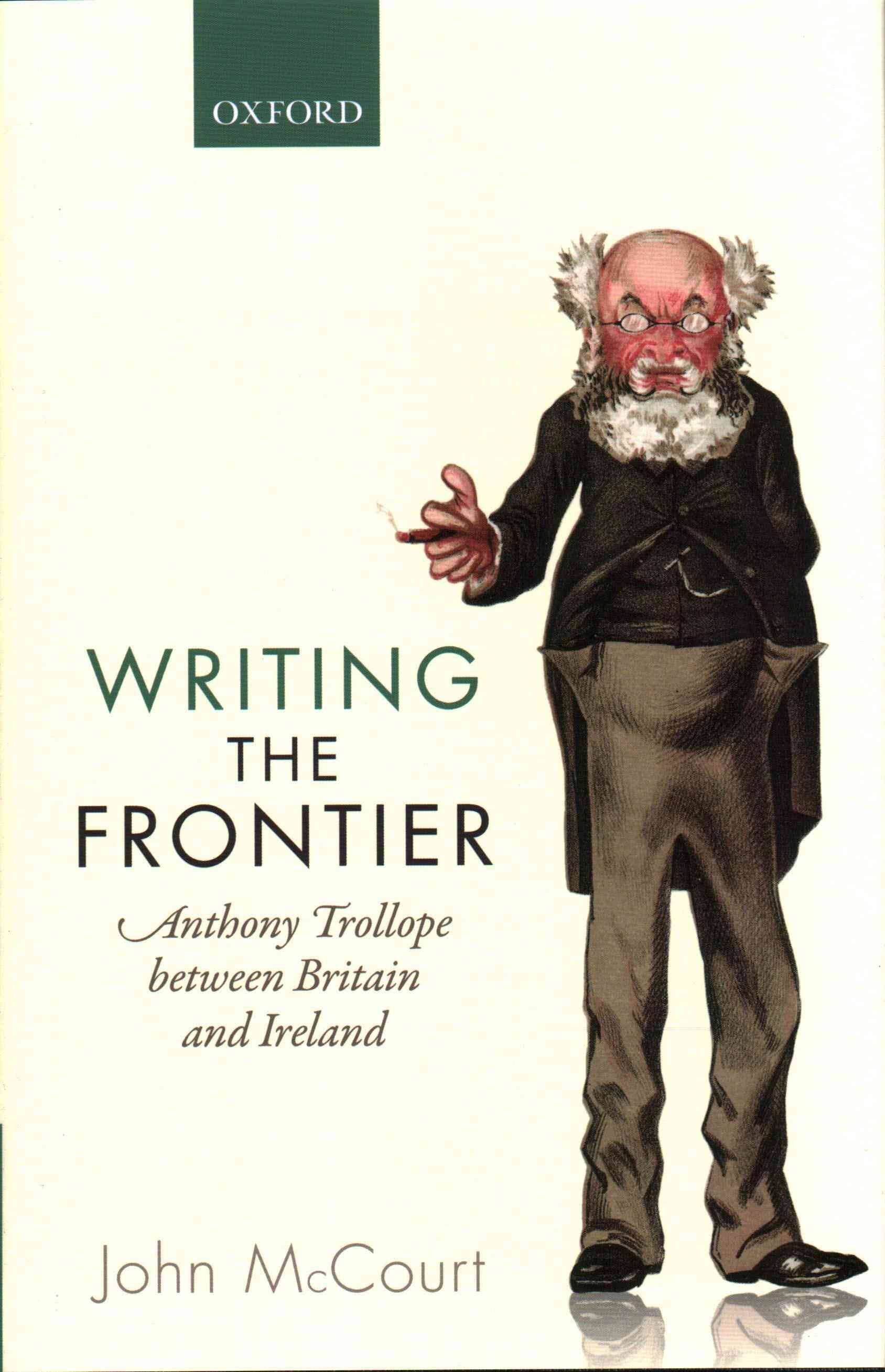

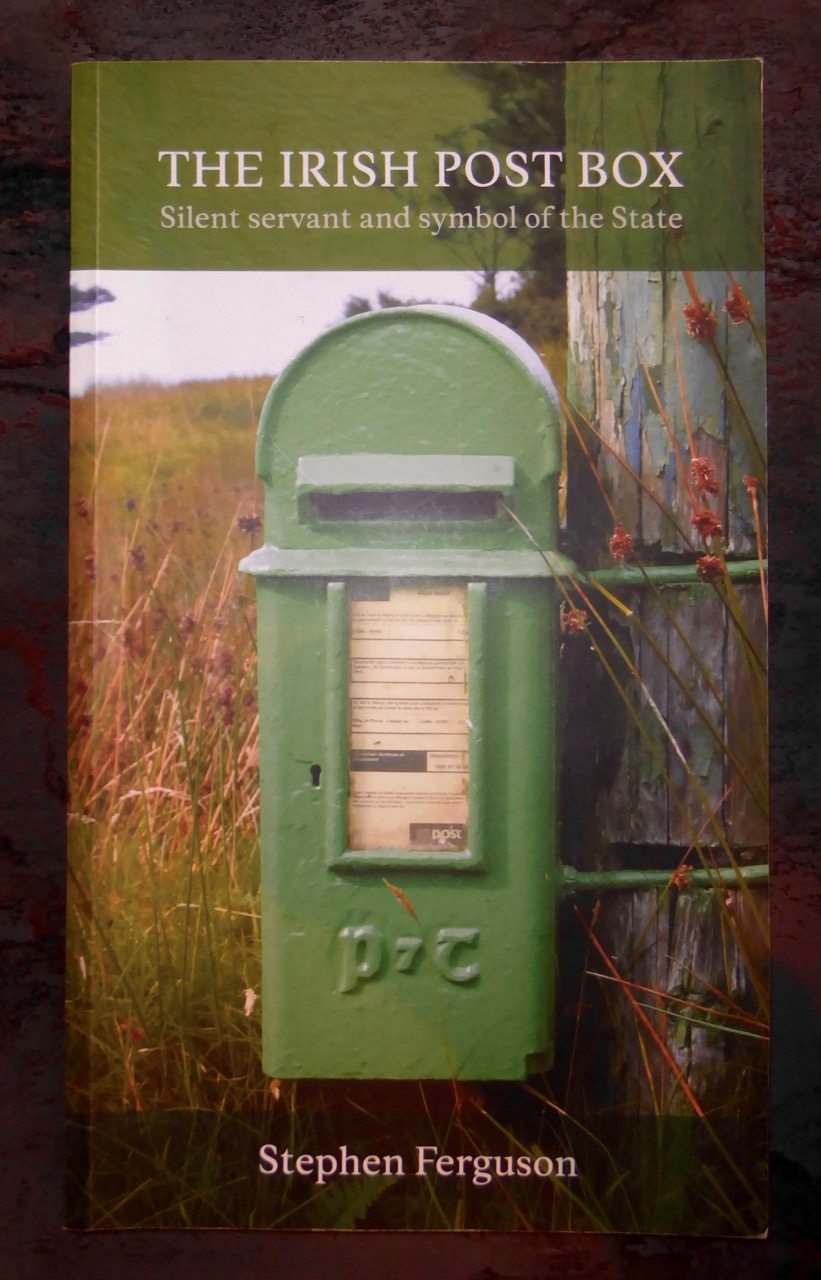

Antiquity is run by Nicola Smyth and her son Junah. Nicola met with her husband Holger, 30 years ago and “…fell in love in front of Holger’s first bookshop…” They travelled in Europe for many years with their four children and many dogs, living in a world of rare books, before settling in West Cork in 2008 and opening The Time Traveller shop. Finola and I came across the Smyths and their books when we also settled in West Cork in 2012. If you had a look into our library at Nead an Iolair, you would see many volumes which have come from Holger and Nicola, especially classic Irish titles on history, archaeology and Irish art and literature.

The Smyths have never been folk to rest on their laurels. Over the last decade or so they have expanded their activities and their geography – experimenting with forays and pop-ups into Cork City, Kinsale and Westport, for example. The Westport shop is still open, under new ownership, as West Coast Rare Books. They have also added to their specialisations Manuscripts, Rare Maps of Ireland and the World, Original Art & Photography, Illustrated Books, Decorative Art, Etchings & Engravings, Lithographs, Botanical Illustration, and rare Vinyl from the 60s to the 90s, a selection of Rare 78’s, and Early Jazz, Rock & Pop albums. If this seems remarkably ambitious, well, it certainly is – and how lucky are we in West Cork to have these offerings right on our doorsteps?

I set out today [Robert was writing this in February] to explore a relatively new venture by Holger – Inanna. Let’s first look at the name: Inanna is a goddess. Worshipped in ancient Mesopotamia, her dates are around 3000 BC – about the same age as Brú na Bóinne, the Newgrange passage tomb, here in Ireland. She is well documented as the Queen of Heaven, and legends connect her with the creation of the cycle of the seasons. She is acknowledged as reigning over love, war, fertility, law and power.

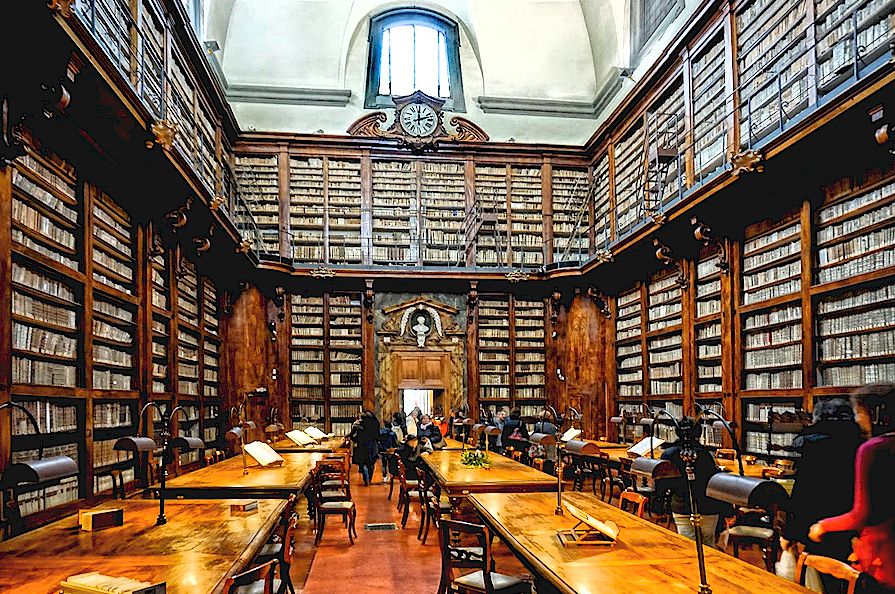

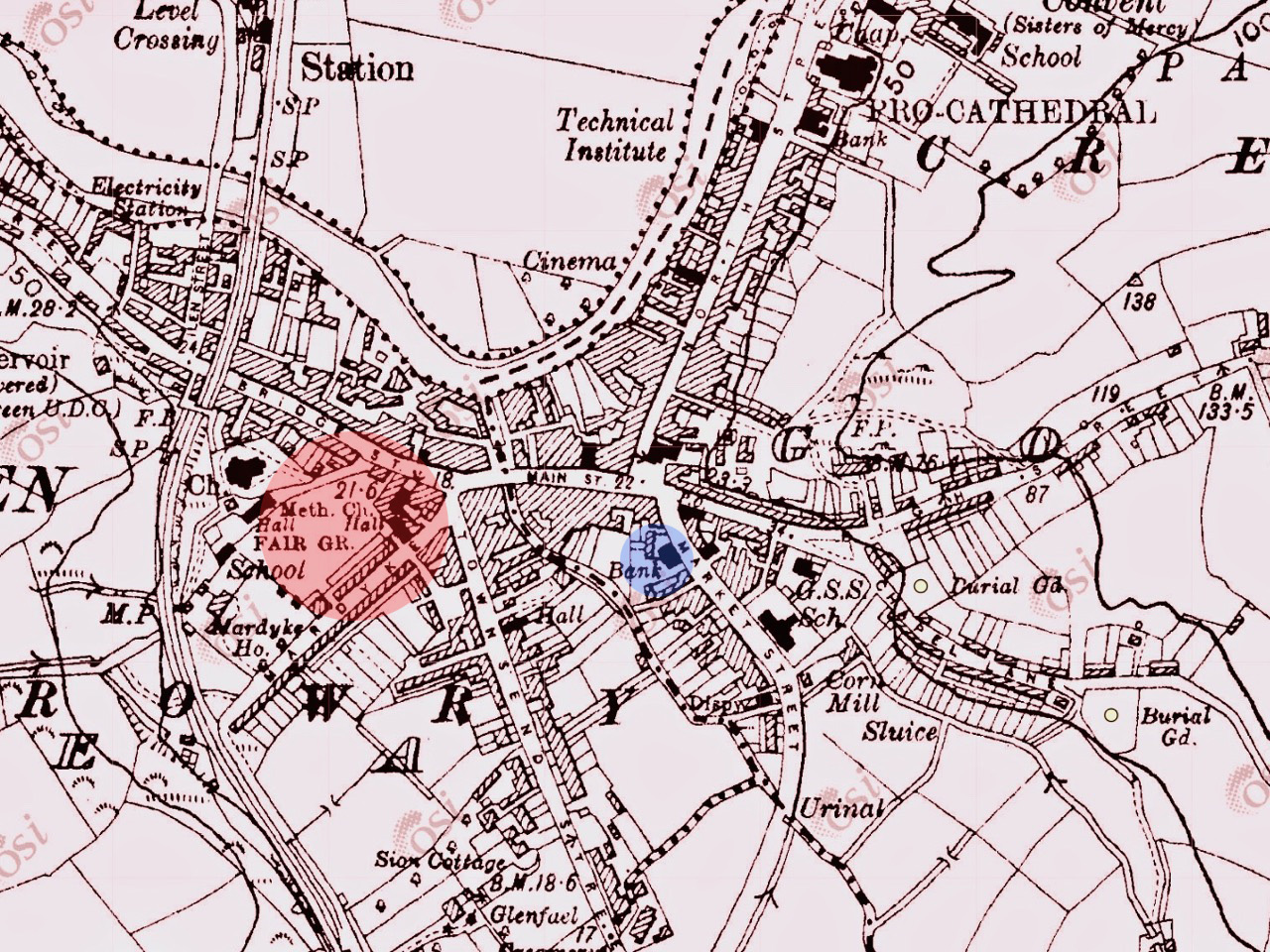

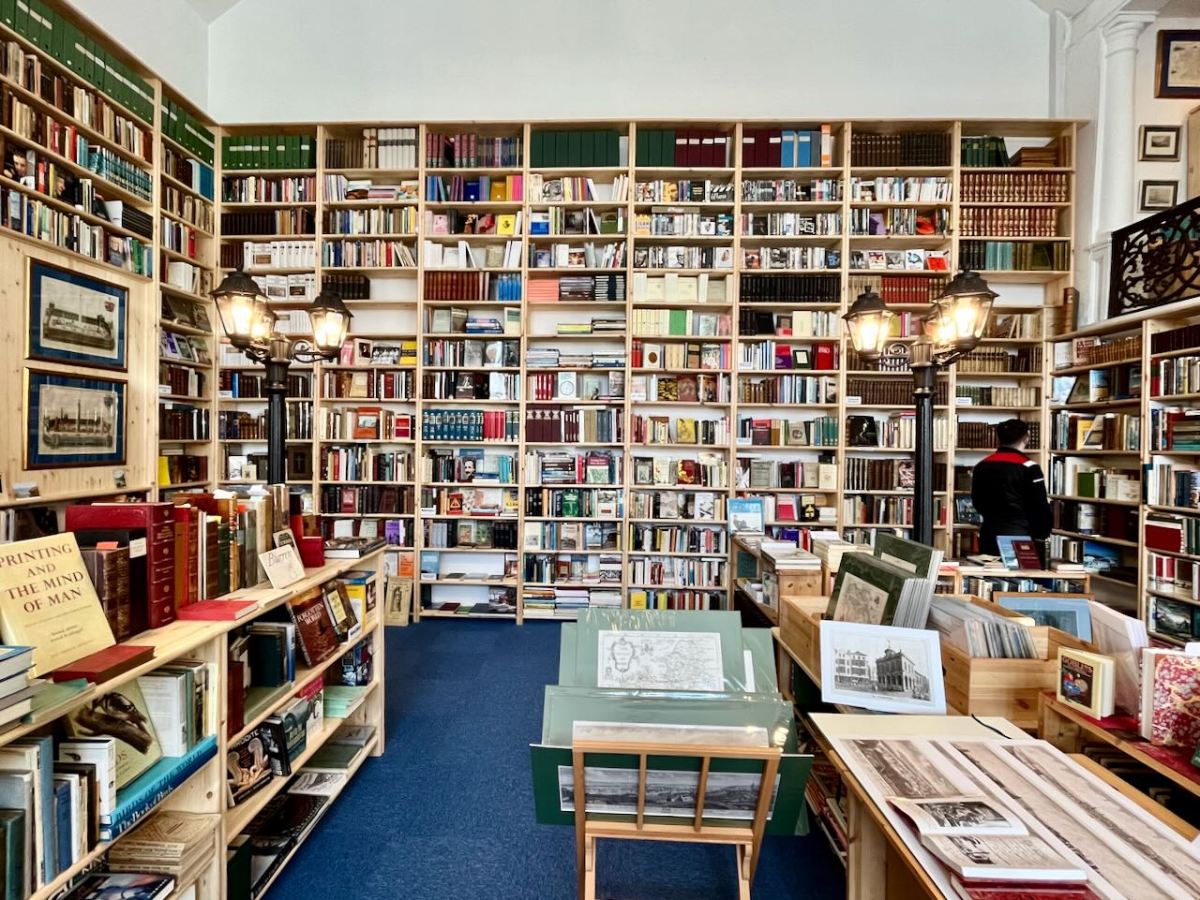

In keeping with the Book Town ethos of utilising historic buildings no longer in use, Inanna Rare Books is housed in the Masonic Hall – I can think of no better use for a building like this. It’s like walking into a grand Victorian library, with books stretching to the ceiling, a mezzanine with an elaborate wrought iron bannister, and the whole place flooded with light from the huge arched windows.

This striking edifice was built in 1863 as a lecture hall. Alas, the lectures didn’t thrive – although such public adult education efforts were very popular at the time – and it was sold after a few years to the Freemasons, and became a Masonic Hall, a meeting place for the masons and a centre for their ritual activities. Over time, their numbers dwindled, but the hall remained in good shape and retains most of its original features, including the timber sash windows.

Over 500 people visit this book store every month. Some travel from afar especially to see this glorious space and browse the collection.

Holger and Nicola’s most recent store is the Still Mill, just off Market Street (above). This, as the name suggests, started off life as a distillery in the 19th century, becoming a grain mill in the 20th century. It had a mill wheel to drive the machinery – that wheel was later broken down and sold off for furniture-making. One of the town’s businessmen, Michael Thornhill, slept as a baby in a cradle made from the wood.

The heritage character of the building is obvious from the outside and stepping inside you are immediately struck by the stately character of the lofty ceilings and deeply-set windows – and how perfectly it suits a bookstore. The focus in this store, named Inanna Modern, is on art – art on the walls, art history and criticism on the shelves, photography, every conceivable form of art book. Holger represents, among others, a Canadian artist, Brooke Palmer, and his intense, colourful images provide a vibrant counterpoint to the lines of sober book covers.

Holger is passionate about using heritage buildings for such purposes. The best buildings in town, he asserts, often sit forlorn and neglected (see The Irish Aesthete for example after example) and what better way to revive them than with a business like this – a perfect match of form and function. Each of his landlords is totally supportive of his efforts, and together they hope to provide models of what is possible in any community.

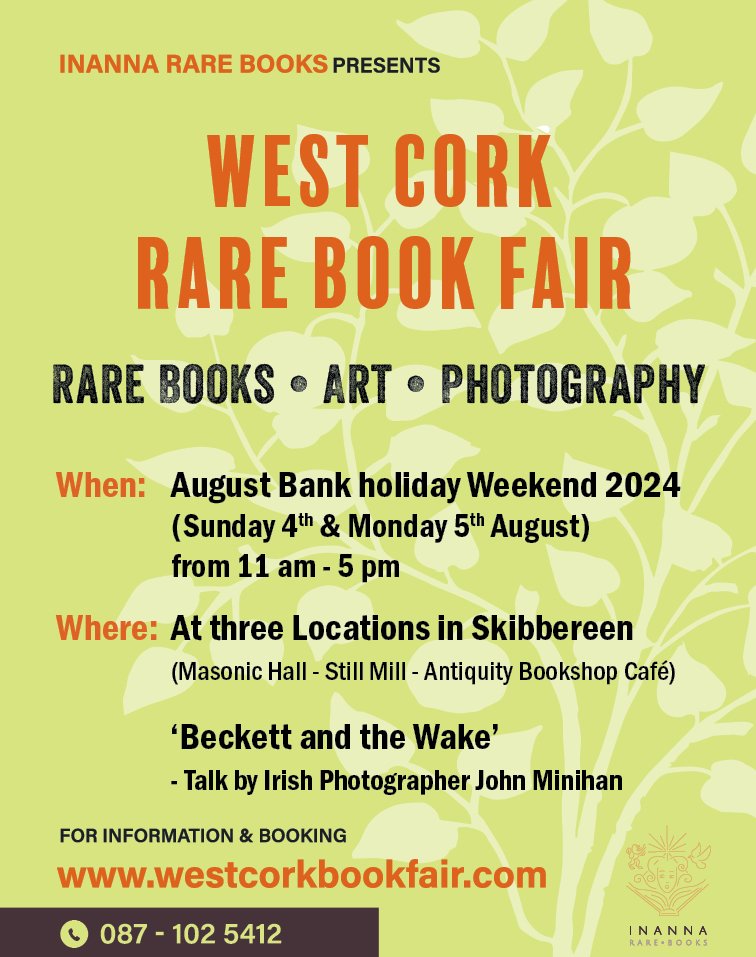

Reader, if you live in Ireland, you are only too familiar with what Holger is talking about – lovely old buildings crumbling and disregarded that, with some attention, could become energetic hubs of cultural activity and commerce. For a budding Book Town, spin-offs are important too. Holger organises the occasional book-related talks or readings and a yearly Rare Book Fair that will take place this year on August 4th and 5th. Meanwhile, for their artists, there was an exhibition at the marvellous Cnoc Bui Arts Centre.

You may not be familiar with the term Book Town – yet! But Skibbereen is well on its way to becoming a shining beacon for bibliophiles from all over the world, thanks mainly to the efforts of the Smyths. How wonderful it is to have people of vision and passion driving an economy for book-lovers, in one small Irish town.