For any student of Harry Clarke stained glass there are delights to be discovered far beyond the main depiction. A host of subordinate or secondary figures reveal themselves to close examination, sometimes only after repeated viewings.

Brendan of Kerry – AKA Brendan the Navigator. Note the borders with their exotic birds

The tall windows I describe in this post typically have three parts – the main section containing a large image of the saint, and an upper and lower section (sometimes called a predella) each of which may contain a separate image/story. In addition, the border around the outside of a Clarke window is always highly decorated in endless imaginative patterns.

The Mary Mother of Sorrows window was executed slightly later than the other windows and shows some stylistic changes. But it illustrates well the three parts to the window and the use of all available space for supporting and secondary characters to tell the story

Clarke was obsessed with detail: there are few white spaces or plain glass in his work. Every inch is filled with richly figured and never-repeated decoration or with additional figures that fill out the story and the symbolism of the central character. These figures tend to fall into a group we can call saintly and a group we can call macabre. Whichever they are, they reflect his vivid imagination and his gift for portraiture.

The Honan Chapel is the Catholic church at University College, Cork. It is a masterpiece of Celtic-Revival Hiberno-Romanesque design and a wonderful place to visit

Designing windows for the Honan Chapel at University College, Cork, was Harry Clarke’s first major commission and launched his career. The windows, finished and installed between 1916 and 1917 contain all the hallmarks of the intricate style he made uniquely his own. I will use four of his Honan windows to look at the cast of supporting characters he employed in his quest to incorporate as much as possible of the saint’s story.

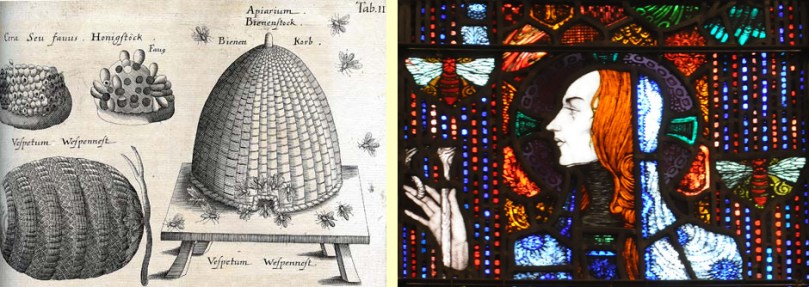

St Gobnait is, famously, depicted in profile, allowing her red hair to take centre stage. She is the patron saint of beekeepers and her bees surround her. Above the main image she is shown spreading her arm (note the honeycomb design of her robe) and extending her staff to prevent a plague descending on her people. She is attended by two maidens and to the right you can see the faces of three men who have not been spared the plague. (There’s another little detail you might spot in this picture!)

To quote Nicola Gordon Bowe, in her magisterial The Life and Work of Harry Clarke:

Harry here shows the delight he took in depicting deformity, disease and the macabre. This fascination with the poles of the beautiful and of the ugly and grotesque is a propensity he shared with many medieval artists.

On either side of St Gobnait another fearful scene unfolds. According to legend, robbers attempted to break into St Gobnait’s abbey but she set her bees upon them and here they are fleeing in terror.

At the very bottom of the panel she is depicted directing the bees and attended by a novice, while on the left a fourth robber runs in panic.

St Brendan the Navigator, with his red beard, gazes serenely out, holding an oar. By his shoulder, his tiny curragh sails westward into the setting sun. In this window pay special attention to the border. Because he was a voyager, discovering the Americas, Clarke decorate it with exotic birds. He intersperses these with tiny roundels of other Irish saints.

Judas suffering on his rock – a medieval vision of misery. Note also the roundels: on the left is St Brigid and on the right is “the poor monk with the iron in his head.” Amazing that Clarke managed to get all that information on to the border of the roundel

In one episode on his seven year journey, Brendan encountered Judas, suffering eternal torture because of his betrayal of Jesus. The bottom panel depicts the scene of the wasted and agonised Judas, while the monks look on in horror. Only Brendan is able to look stoically forward.

Detail from the St Ita window

St Ita (the first photograph in this post) was the daughter of a chieftain but renounced all worldly things to live a life of poverty and to teach. Once again, Clarke uses tiny roundels to depict other saints associated with Ita: Brendan, Colman, Finbar and Carthage.

Below her feet is another tableau, depicting a prayerful scene in which she is attended by two holy women and St Colman and St Brendan. The portraiture of the the two saints is exquisite.

St Albert of Cashel – a little known saint who journeyed to Ratisbon in Germany on a conversion mission

A last window from the Honan Chapel – this time St Albert of Cashel, depicted as a seated bishop. In the top portion he is depicted converting the people of Ratisbon in Germany. Once again the individuals are beautifully drawn and sumptuously dressed. I particularly love the red hair – always a feature of a Harry Clarke window.

Citizens of Ratisbon listening to St Albert preaching

I highly recommend a visit to the Honan Chapel if you’re in Cork. See Robert’s post, Cork Menagerie, for an in-depth look at the mosaics. And take your time – the windows (there are several more than the ones I’ve used in this post) reward patient and detailed study. For more on Harry Clarke’s stained glass, see my post The Gift of Harry Clarke, which will walk you through an analysis of his style and his influences.