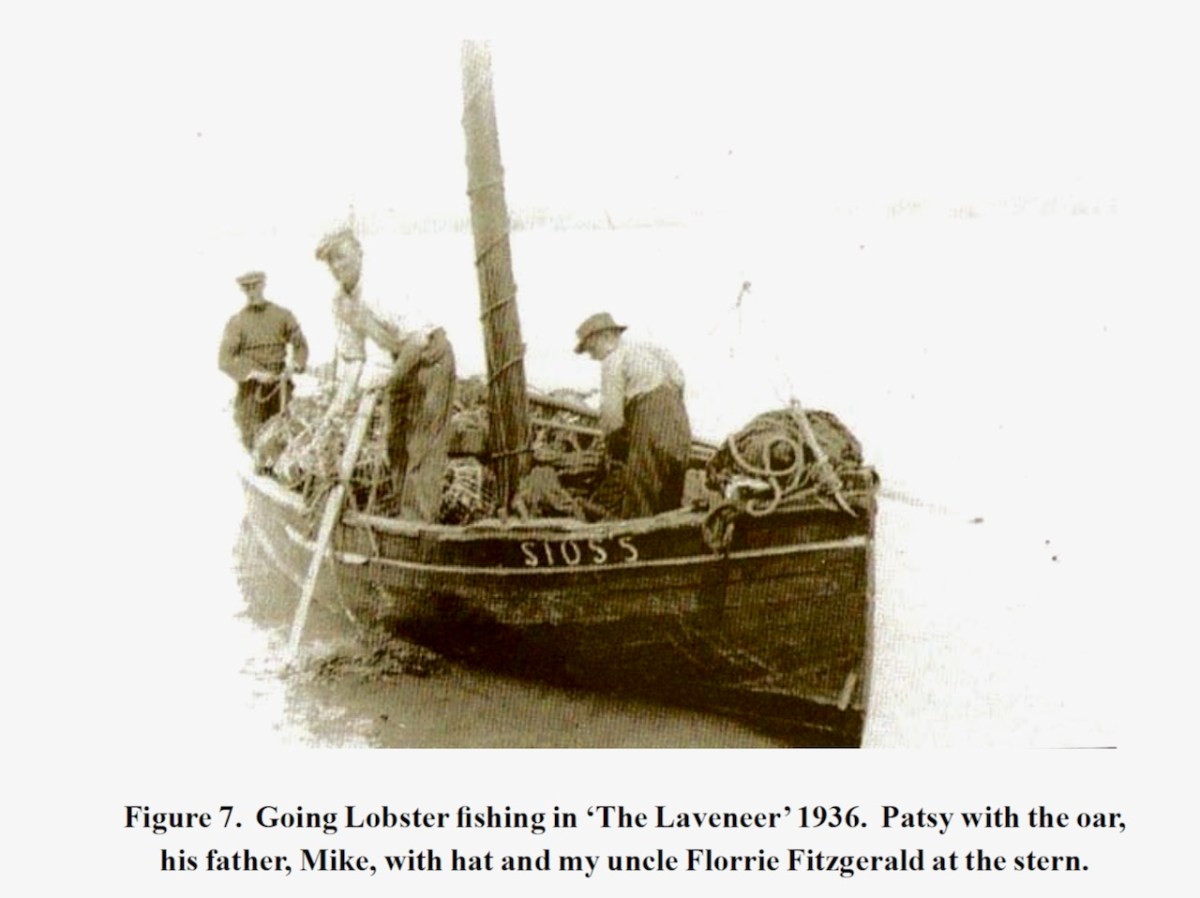

Fishing was a huge part of how the islanders made a living and fed themselves and their families. For how this was conducted I am relying on Hester’s detailed account. She writes about her parents’ generation and also about her own – her husband, Patsy, also went fishing. I will use Hester’s words, from her memoir, Misty Memories, lightly edited for a bit of brevity.

Most of the men from the islands around went Lobster fishing every Summer. There were 27 lobster boats in Heir Island when I was ten years old and at school there. Each boat had a crew of three men. That meant that 81 men left the island from May to September and went to Kinsale and Cobh – a long journey along a rough coastline in very shallow sailing boats.

A traditional Heir Island Lobster Pot. © National Museum of Ireland*

Lobsters were caught in baited lobster pots, made of willow twigs and anchored in deep water. The men made the pots themselves during the winter months. Some were very skilled and others helped them – they worked as a team or ‘meitheal’ as it is called in Irish. They had special tools for the job and a sort of mould around which they wove the twigs so that the pots had the proper shape. Rowing for miles to the other islands and to the mainland to get enough twigs, they carried big bundles on their backs, often having to walk four or five miles back to the boat.

The authority on traditional Heir Island boats is Cormac Levis, and this book is a must for anyone interested in this topic. It is currently out of print but you might be able to find a copy online. Cormac is planning a second edition for 2026.

Lobster boats had three sails and the smallest one of these, called the ‘Towel Sail’, was used to make up a sleeping tent over the boat’s stem. Just as with the lobster pots, the men made the sails themselves. There was a lot of work in them and some of the men were really expert at it. Sails for the lobster boats and other bigger boats were made of canvas with a rope sewn firmly all around the edge. They made special eyelets across the sail to hold the reef cords so the sail could be made smaller in high wind.

Cormac’s own boat, the Saoirse Muireann, is a traditional towelsail yawl, built at Hegarty’s boatyard

There were lots of preparations to be made for going lobster fishing. When pots and sails were right, the boats were filled with ballast and sunk in deep water for two weeks to close the seams after winter dry dock. Then they were taken up, painted inside and tarred outside. The three-man crew came together to put in the ‘pig-iron’ – slabs of iron for ballast to keep the boat from capsizing. They then put in the steer and the helm and a big anchor. Special ropes and stones were prepared to tie the pots deep in the fishing ground. They called these the ‘Killick rope and stone.’ Next, they added the utensils – a tin basin for washing and for making bread, pots, a kettle, tin plates and mugs. Foodstuffs, including the flour for making bread, were kept in the little cupboard built into the stem of the boat. Drinking water was stored in a ‘breaker’, a round wooden barrel that held a few gallons. They also brought potatoes and coal for the fire.

This photograph shows the relative size of the three boats used in the Heir Island fishery. Left to right is the Saoirse Muireann, the Saoirse and the Hanorah

They had an iron bastible pot they called ‘the oven’ to hold the coal fire. The set-up for the fire had to be very carefully and safely arranged. A thick piece of cast iron was placed on the thwart mid-way in the boat and the fire pot was put on top. All the cooking was done on this fire. A pig’s head, potatoes and vegetables were all boiled together in an aluminium bucket. They also cooked fish. One man was in charge of the bread-making. They made white soda bread – very thin cakes that baked quickly. Bits of soot sometimes got into the white flour and the bread would have black streaks in it.

This is the largest of the boats. This is the fabled Saoirse, a replica of the boat sailed around the world by Conor O’Brien is 1923-25. It is a 42′ Ketch and the design was based on a traditional Roaringwater Bay fishing boat

There was smoke and soot everywhere and the men’s skin and clothes were black on their return home and took weeks to get clean again. The combination of soot, salt water and the hauling of ropes caused the skin of their hands to crack. Their ‘intensive care lotion’ was to ‘pee’ on their hands to toughen the skin. They all put on lots of weight during the lobster season and when they came home and their skin cleared of soot, they had a great healthy colour.

Joe says in his account In 1934, when I was thirteen, we got a boat built by Harry Skinner at Baltimore.This was a small light boat, not the boat above, but I am including this image as it is of a Skinner-built mackerel yawl. It’s from this source.

Washing and shaving were done by sitting the basin of water into the open end of a lobster pot to keep it steady. The same tin basin was used for everything – washing, shaving and making bread. Three towels had to do them for the whole time they were away and these towels were jet black when they came home. They wore flannel underwear – ‘the wrapper’ was a thick vest top with long sleeves and ‘the drawers’ were full length long-johns. The women made all these by hand from their own patterns. All the seams were sewn by hand – herringbone stitch to make sure they never ripped. The younger men didn’t like wearing this heavy underwear but they soon found they were so cold out at sea that they were glad to have them. Each man had three sets of underwear kept in a flour bag with their other clothes and a small bottle of Holy Water.

The Hanorah is another traditional boat built at Hegarty’s – this one was used for mackerel fishing

The lobster-men were really skilled at their job. They knew exactly where to get the lobsters and how to handle them without getting bitten when moving them from the pots to the storage basket. This basket had to be kept submerged under a buoy until they went ashore and sold their catch to buyers along the coast – lobsters had to be sold alive.

A closer image of the Laveneer loaded with lobster pots

The three men had to get on with each other in a very small space and co-operate together for their own safety. They said the Rosary together every evening and used their Holy Water to bless themselves, their boat and their pots. Patsy’s father, Mike O’Neill (called Mike, the Laveneer or Mike Mary Harte) was considered one of the best boatmen around. He was described in Heir Island as “the safest man going out the harbour mouth” (Baltimore Harbour).

This is aboard Cormac’s Saoirse Muireann this summer – it will give you a feel for the kind of room we had in the boat

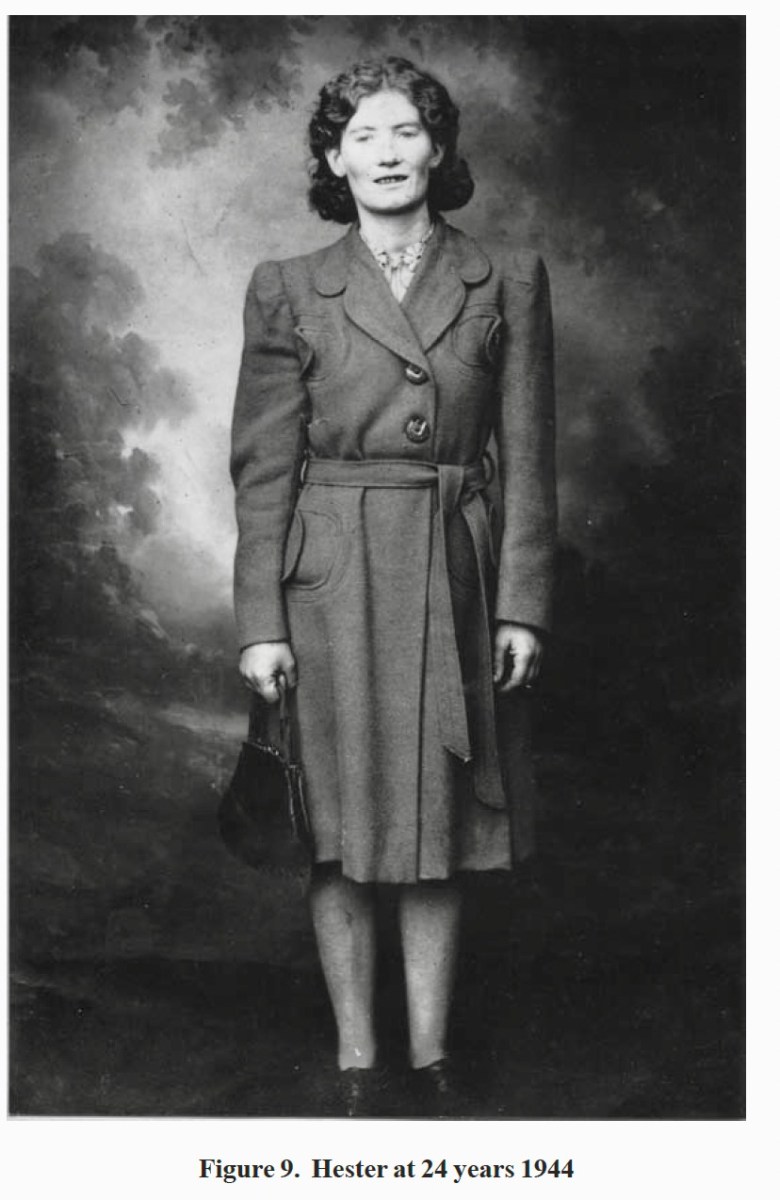

Hester’s memories above were of her father’s generation, but her husband, Patsy also went to sea when he needed to and it was an anxious time for Hester.

In the last few winters before we left Heir Island Patsy went herring fishing to Dunmore East in County Waterford. He went with a crew from Cape Clear in a small trawler called ‘The Radiance’. Herrings were in great demand in those days and when they had a week of good catches, he sent the money home in a registered letter. I tried to save some of it for the day when we might be able to get a place in the mainland. I remember how the children and I used to write letters to him and address them to ‘Boat Radiance’ c\o Dunmore East Post Office where he picked them up when they landed their catch, and wrote back to us. He could be away for up to three months in the depths of winter and I was always worried for his safety in the stormy seas on those cold winter nights.

It might be a while before I get back to Hester and Joe, but there is lots more to tell from their accounts on life on a small island in Roaringwater Bay