Not all stained glass windows are great works of art but all have a story to tell. Sometimes the story is about the subject of the window (the iconography) and sometimes it’s about the person who is remembered or even the one who is doing the remembering. Sometimes it’s about the craft, or the times, or the influences on the artist. Let’s take a look at a few West Cork windows.

This one (above) is in Ardfield, south of Clonakilty and close to Red Strand. There is no identifying writing on the image but we know that this is St James. How do we know? Well, the church is St James’s and there’s a holy well dedicated to St James nearby. But mostly we know because, even though he looks like a stereotypical saint with the beard, the halo and the long robes, there are symbols to identify him. St James, or San Diego de Compostela, has given his name to the great Camino pilgrimage and he is mostly depicted, as in this portrait, as a simple pilgrim, carrying a staff with a gourd for water suspended from it, and wearing the scallop shell, symbol of the pilgrim.

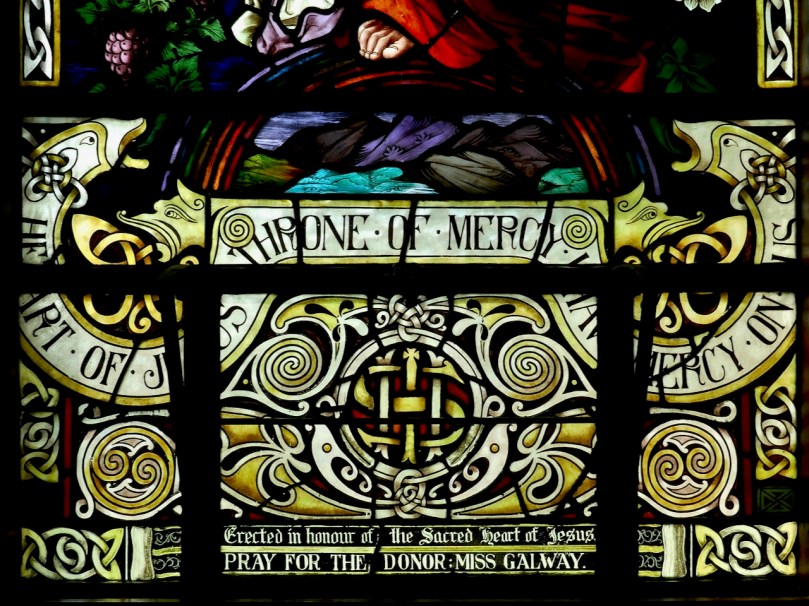

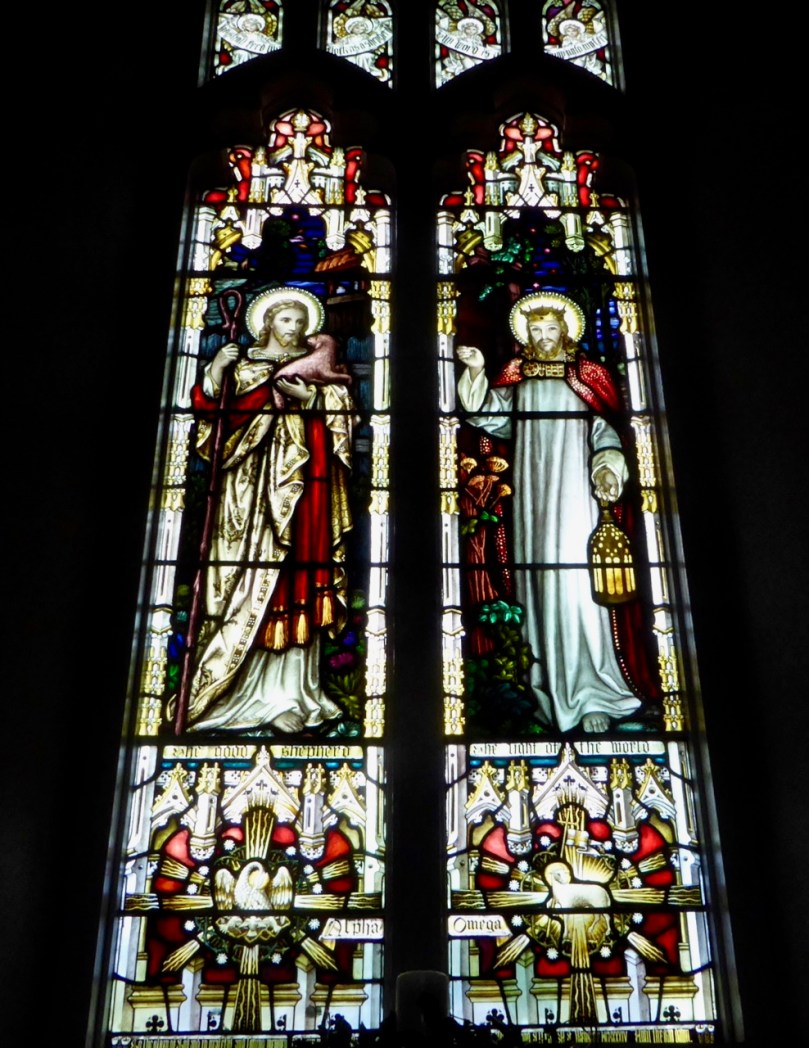

The first three photographs in this post are all from St James Catholic Church in Ardfield, by Watson of Youghal

The other thing that’s really interesting about this window is the use of Celtic Revival interlacing. It’s beautifully and expertly done in all the windows in this church, and it marks those windows as the work of Watson’s of Youghal, our own great Cork stained glass producers, whose work can be found all over the county and the country. Parish priests would often specify their wish for this type of ornamentation in preference to the usual gothic canopies and it became a hallmark of Watson’s work. I will write more about this in a future post, so this serves as an introduction.

Windows in Catholic churches most often take as their subject the iconography of the new Testament and this occasionally includes images from the Book of Revelations. A favourite, because it is a Marian image, is the verse 12: 1-17, which goes like this:

1 And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars: 2 And she being with child cried, travailing in birth, and pained to be delivered. 3 And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads. 4 And his tail drew the third part of the stars of heaven, and did cast them to the earth: and the dragon stood before the woman which was ready to be delivered, for to devour her child as soon as it was born. 5 And she brought forth a man child, who was to rule all nations with a rod of iron: and her child was caught up unto God, and to his throne

While I have seen many depictions of the woman clothed in the sun with the moon and stars, the red dragon is quite rare, and this one (above and the two below), done by Mayer of Munich for Clonakilty Church of the Immaculate Conception, is striking. The artist has given each of the dragon’s heads fearsome fangs and snakes’ tongues: each has a crown (a rather cute one) and by dint of leaving out horns on two of the heads there are indeed ten horns.

The Book of Revelations has been traditionally ascribed to John the Evangelist, whose symbol is the eagle. Many modern scholars now believe it was written by John of Patmos but this depiction (below) is the traditional one of John as the beloved, young, slightly androgynous apostle, writing down what he is seeing in the revelation.

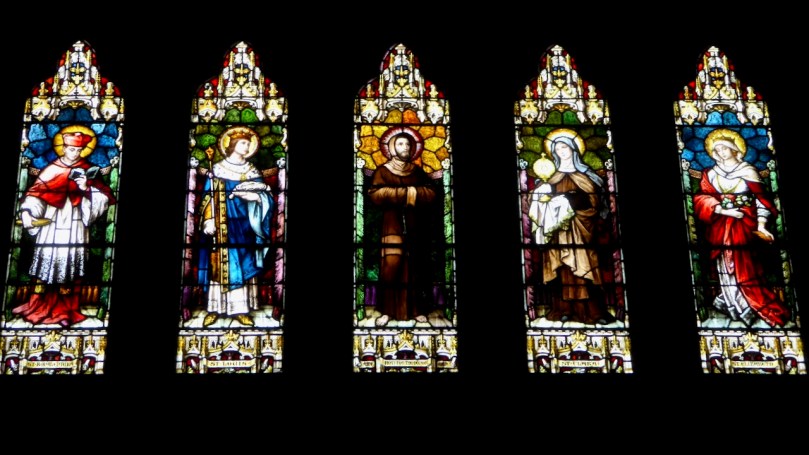

I was also struck in the same Clonakilty church by the huge rose windows with rows of saints beneath them. While the east window features Irish saints, the northern window pictures five saints associated with the Franciscans, possibly because of the proximity of the ruined Franciscan Abbey in Timoleague. They are conventionally, but beautifully done, depicting Saints Bonaventure, Louis, Francis, Clara and Elizabeth of Hungary.

The St Louis window that I am more familiar with is by Harry Clarke, in the Castletownshend Church of St Barrahane, and I have written about that one in my post The Gift of Harry Clarke. This depiction shows a young St Louis, who was King Louis IX of France, carrying a crown of thorns.

St Louis was a complex character, renowned for his holiness and beneficence and for feeding the poor at his own table. He was also an art lover and collector of relics, building the famous Sainte-Chapelle to house them, including the crown of thorns, the prize of his collection. While he instituted important law reforms and championed fairness and justice for his citizens, he also expanded the Inquisition, persecuted Jews, and participating in two crusades against Islam. Nothing, apparently, that prevented him being canonised less than 30 years after his death.

The depiction of St Elizabeth (furthest right) also struck me as very beautiful

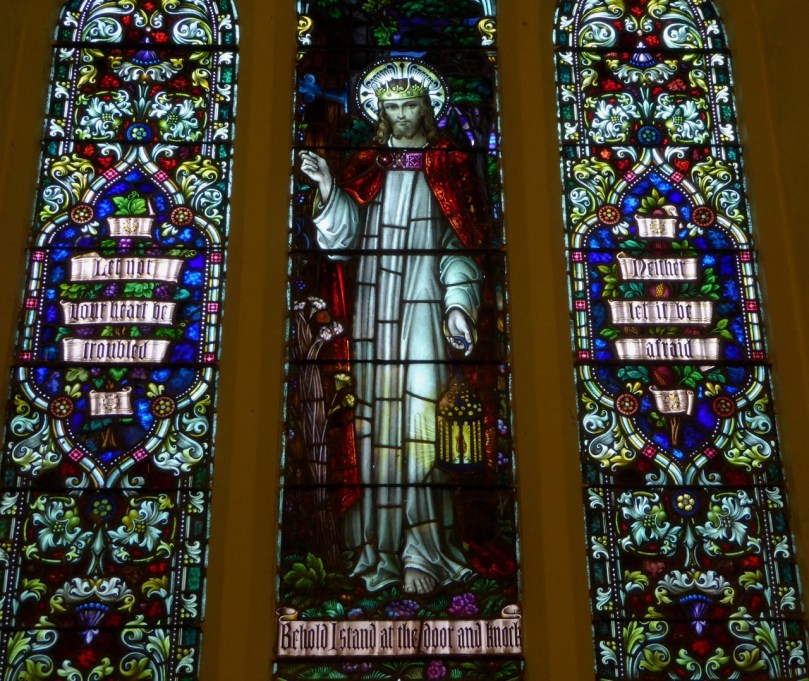

My final example for today is a window by the Irish Firm of Earley in St Finbarr’s church in Bantry. This caught my interest for several reasons. First, it’s a fine windows and not imported but executed by the Earleys at a time when Irish stained glass manufacturers were competing for business against cheaper, mass-produced windows from Britain and Germany. This is significant because the windows were ordered and paid for by William Martin Murphy, one of the richest captains of industry in Ireland and a promoter of home-grown manufacturing. They were installed in 1914, only a year after the 1913 Dublin Lockout had made him a notorious and hated figure in Ireland – a reputation that some historians are trying to rehabilitate now, or at least to provide a more balanced picture of the man. He was from West Cork and the window is to honour his parents.

But the subject matter is also telling. On top we have Jesus in the act of saying to Peter, “Thou art Peter and upon this rock I will build my church” (below). In case we are in any doubt, an angel overhead carries the pontifical tiara. This is a reminder to Catholics to bow to the authority of Rome in all things, and was characteristic of the kind of Ultramontane Catholicism that typified the new Irish State. See my post Saints and Soupers: the Story of Teampall na mBocht (Part 7, the New Catholicism) for an explanation of what drove the Irish church in this period.

Underneath, St Finbarr is also receiving a bishop’s mitre from an angel – the message is a subtle one but well understood by parishioners as drawing a parallel between the lines of authority emanating from Rome as much in Biblical times as in ancient monastic Ireland. (The windows in Killarney Cathedral are all in this vein.) Perhaps for William Martin Murphy there was an ultimate point to be made about subjection to proper authority.

So take a closer look at familiar windows – you might find depths in them you haven’t noticed before, stories that are hidden behind all that colour (like one of my own personal favourites, below.)