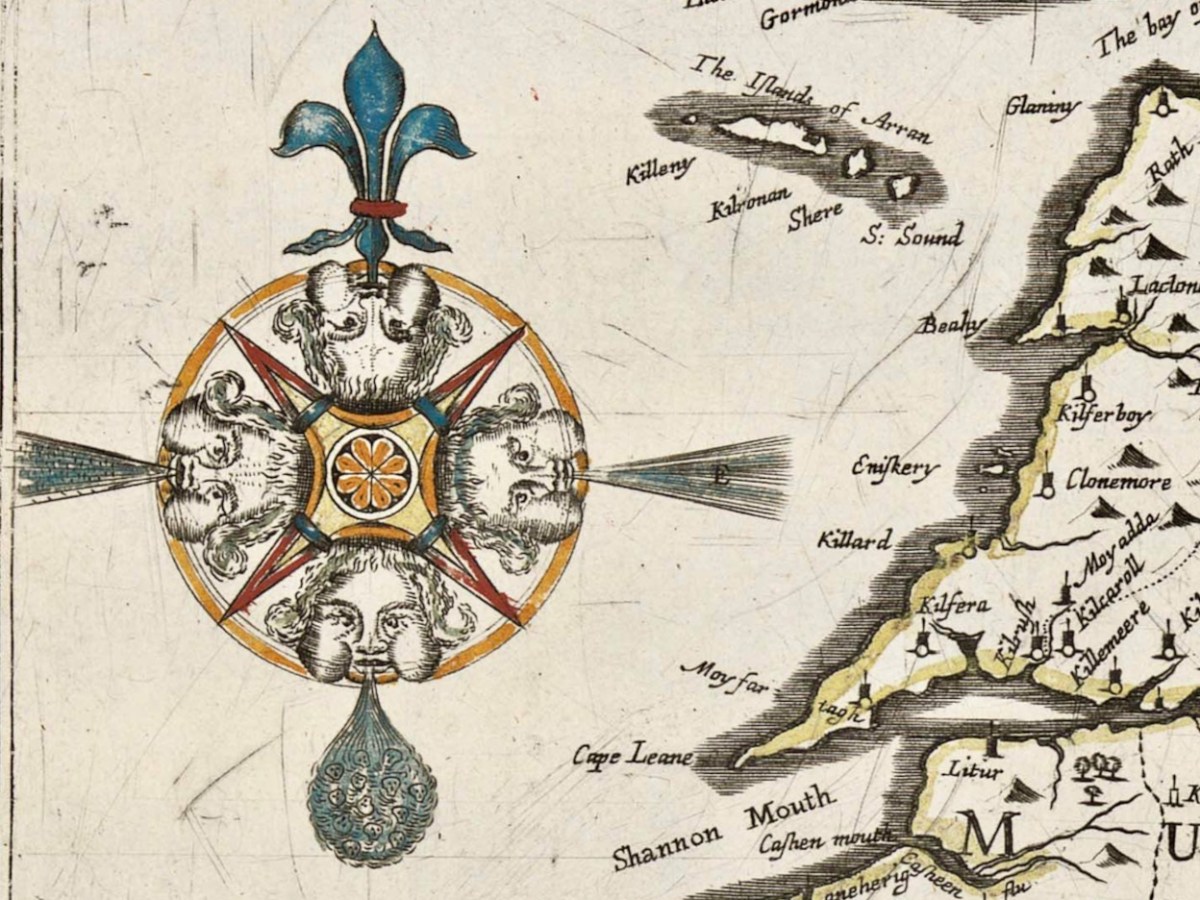

Here’s a fascinating title block. What are these cherubs doing? The couple on the left are excited about the operation of a magnetic compass; the little drummer is wearing a plumed helmet and has a decorated sash around his torso; cherub number 4 is bearing a spherical astrolabe, while the three on the right are actively engaged in surveying – using a Gunter’s Chain. This latter instrument – by the way – achieved, in the seventeenth century, something we seem to find tricky in our present day: the simple reconciling of imperial and metric measurements!

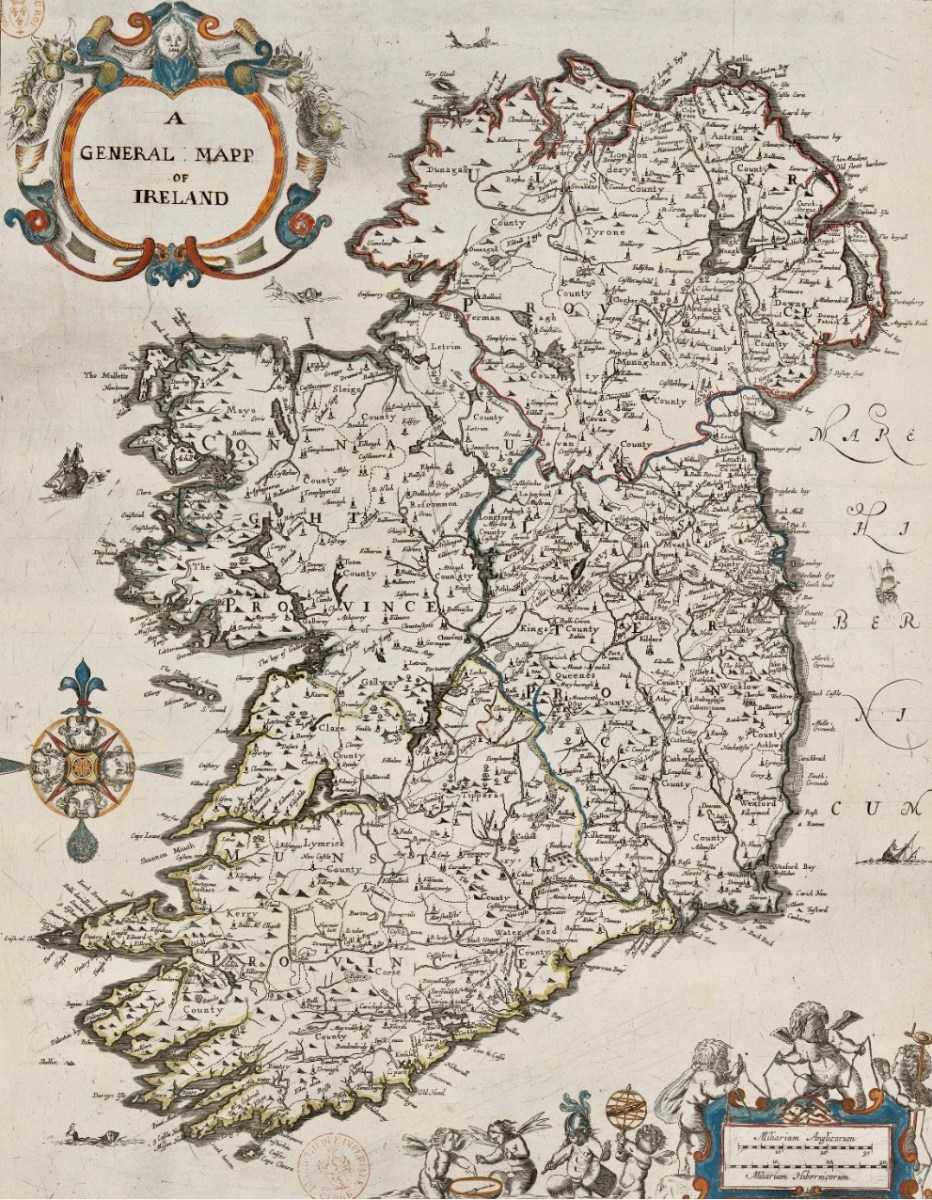

The cherub image, and the two above, adorn and decorate a remarkable document: the Down Survey map of Ireland. As this survey was ordered by Oliver Cromwell after an cogadh a chriochnaigh Éire (the war that finished Ireland) it seems strange that the north point of the compass is a fleur-de-lis: usually a symbol of the Virgin Mary. Cromwell himself was, of course, a Puritan and a Protestant and his actions in Ireland were aimed at subduing the rights and practices of Catholics, driving them ‘to Hell or Connaught’ – the poorest lands to the west of the Shannon river.

The decade following the Irish rebellion of 1641 witnessed a particularly turbulent period of warfare in Ireland between Catholic families and invaders from England, who were led by the dispossessed followers of the crown during the Civil War, which lasted through most of that period. The Act for the Settling of Ireland (1652) imposed penalties including death and land confiscation against Irish civilians and combatants after the Irish Rebellion and subsequent unrest. British historian John Morrill wrote that the Act and associated forced movements represented …perhaps the greatest exercise in ethnic cleansing in early modern Europe…

Sir William Petty – in charge of the Down Survey. Portrait by Godfrey Kneller, courtesy Romsey Town Council.

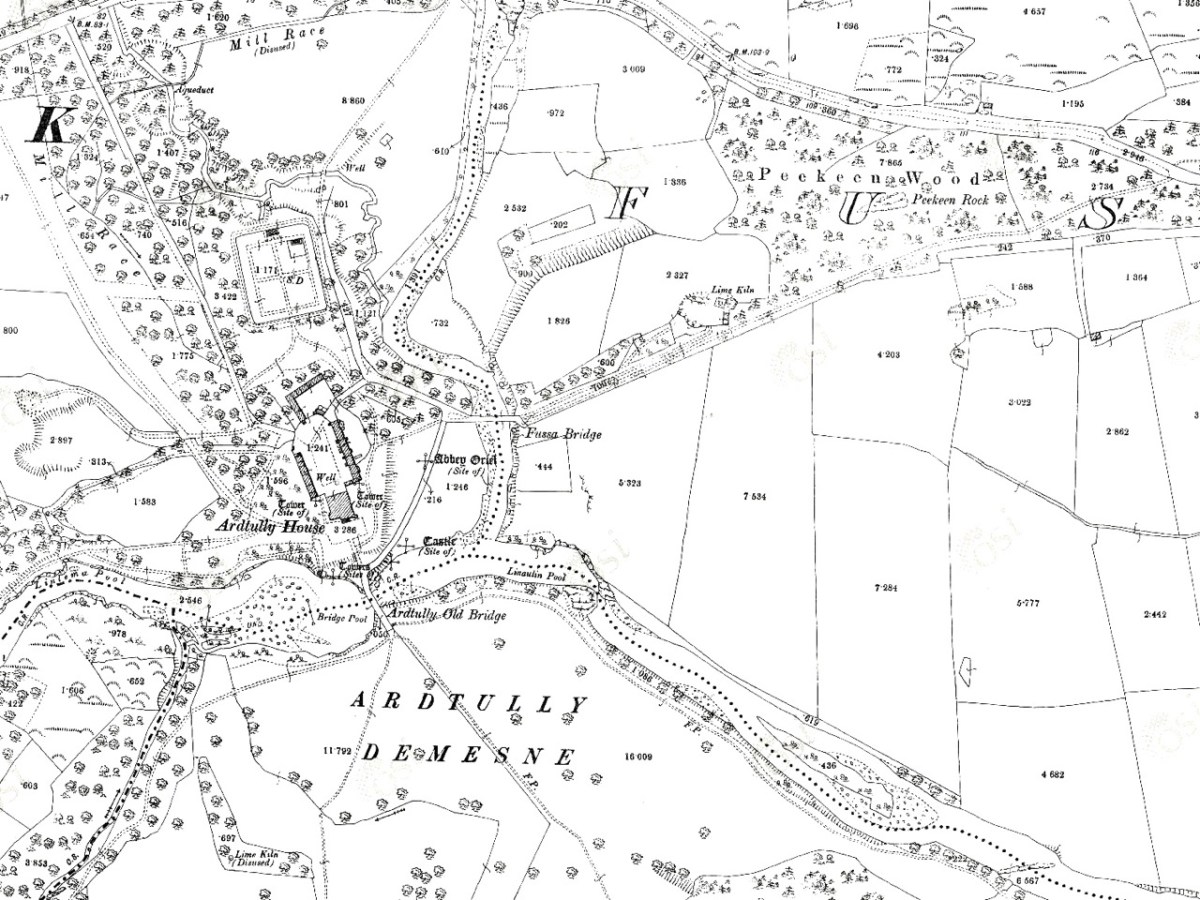

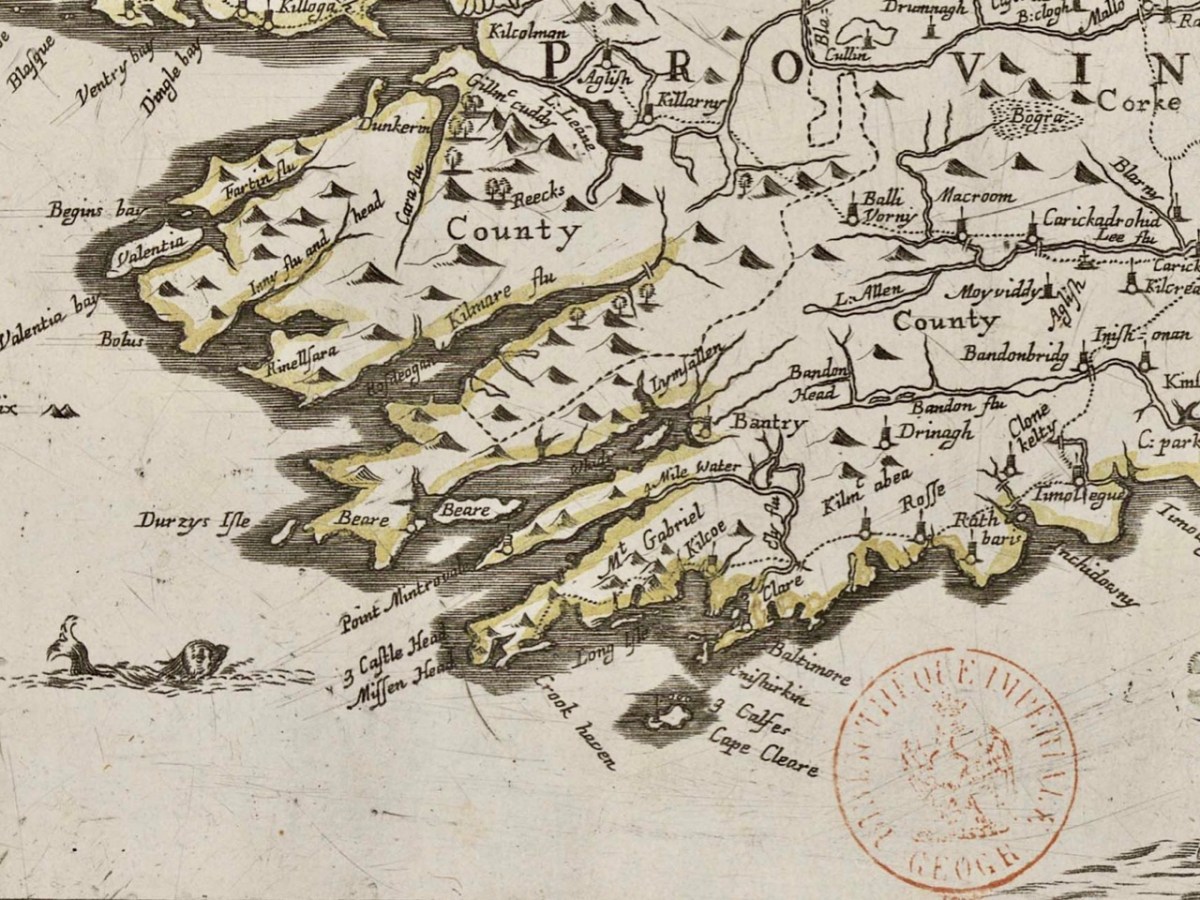

. . . Taken in the years 1656-1658, the Down Survey of Ireland is the first ever detailed land survey on a national scale anywhere in the world. The survey sought to measure all the land to be forfeited by the Catholic Irish in order to facilitate its redistribution to Merchant Adventurers and English soldiers. Copies of these maps have survived in dozens of libraries and archives throughout Ireland and Britain, as well as in the National Library of France. This Project has brought together for the first time in over 300 years all the surviving maps, digitised them and made them available as a public online resource . . .

http://downsurvey.tcd.ie/

We are very fortunate to be able to freely access – through the internet – this website which contains all available copies of the surviving Down Survey maps, together with written descriptions (terriers) of each barony and parish that accompanied the original maps. These bring out for us very detailed information on what the surveyors recorded in Ireland three and a half centuries ago.

Examples from map extracts, showing the quality of reproduction which can be obtained from the site. These show our own West Cork, with local names that have a familiar ring: Ballidehub, Skull, Rofsbrinie, Affadonna. Having discovered this resource, we know this site will be invaluable in our history researches. Look out for my next post exploring the fine detail of the survey.