There’s a wealth of tales to be told about the first decades of independent Ireland. The 1920s and 1930s saw a flourishing of confident projects portraying a nation on the cusp of change, establishing itself in Europe and beyond. One such was the hydro-electric scheme at Ardnacrusha on the River Shannon. Foundations were laid in 1925 and works completed within four years, providing the young country with what was then the world’s largest power station. The intention was to enable everyone in Ireland to avail of the most trendsetting modern commodity: electricity.

The documentary photo above looks like a scene from a science-fiction film: it’s the control station at Ardnacrushsa, shortly after the completion of the project. This, and many other of the illustrations which I will refer to, are taken from the excellent ESB Archives: I am very grateful to them for the use of these. The building of the huge dam and power station was documented in fine detail – and not just in words and photographs. The notoriously outspoken and visionary artist – Seán Keating – chose to record the accomplishments in his own medium, painting.

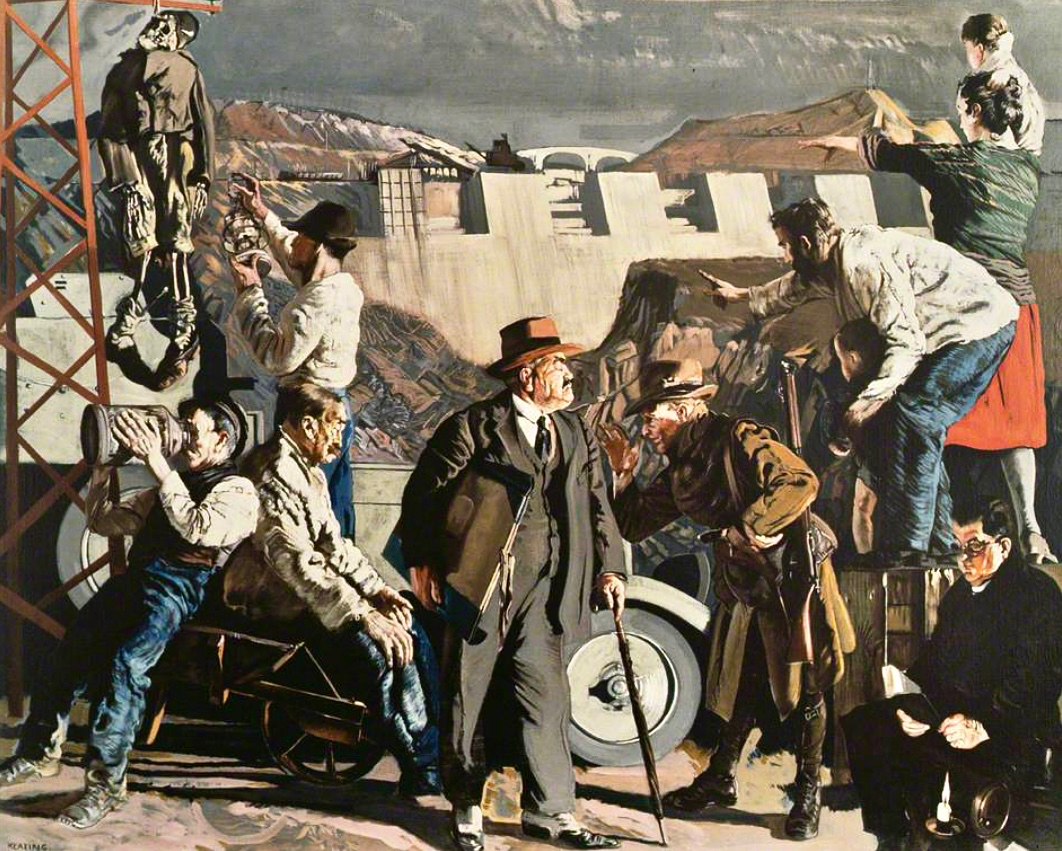

This is one of Keating’s works from the time: Night’s Candles are Burnt Out. (Thanks to Gallery Oldham). It is, perhaps, the finale of his series drawn and painted during the construction of the works – which he undertook on site under his own initiative and without a sponsor. Art historian (and biographer of Keating) Dr Éimear O’Connor suggests:

. . . Keating went down to Ardnacrusha because he knew that the construction project was emerging history. It was all happening around where he was born and raised. The machinery was going to carve up this landscape that he saw as ‘a medieval dungheap’, that was how he described it in later years. And this was a metaphor for him, the whole thing was all about Ireland moving forward into modernity. Night’s Candles features the dam at Ardnacrusha, but also includes a group of figures in the foreground, all of whom represent different aspects of what Keating saw as the Ireland of the day. When he showed it at the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin, it was called ‘the problem painting of the year,’ which Keating thought was hilarious. They couldn’t get their heads around this idea of what he was trying to do at all . . .

O’Connor: Seán Keating: Art, Politics and Building the Irish Nation, 2013 (Irish Academic Press)

In this detail from the painting we see Keating himself (top right) together with his wife and sons, pointing to the vision of Ireland’s future. On the left of the full painting is Keating again, inspecting a hanging skeleton, perhaps reminiscent of the Famine. Most significantly, perhaps, at the bottom right is a priest reading by the light of the candle. O’Connor is clear about this portrayal:

. . . It tells you an awful lot about Keating and his attitude to the Church at the time. Like many others in the cultural sphere in Ireland, he was disappointed with post-Treaty Ireland, with successive governments and the Church, who were in cahoots, if you know what I mean. He knew well that the whole country was tied up with them, and with that kind of organized religion that was deeply conservative. And Night’s Candles is very much an expression of that disappointment, I think . . .

O’Connor: Seán Keating: Art, Politics and Building the Irish Nation, 2013 (Irish Academic Press)

It’s worth dwelling on this painting a little longer, and viewing Keating’s thought processes, through O’Connor’s eyes:

. . . What Keating was trying to do was reflect upon a country on the brink of change. It was in those years, in the 1920s, that the term ‘gombeen man’ came into being. We all know that it means the kind of businessman or politician who’s making money off the backs of everybody else. And that’s the gombeen man in the middle of the painting. I think it’s quite clear that Keating’s hope was that modernity, as represented by Ardnacrusha, would end all that stage-Ireland paddywhackery that had prevailed for years . . .

O’Connor: Seán Keating: Art, Politics and Building the Irish Nation, 2013 (Irish Academic Press)

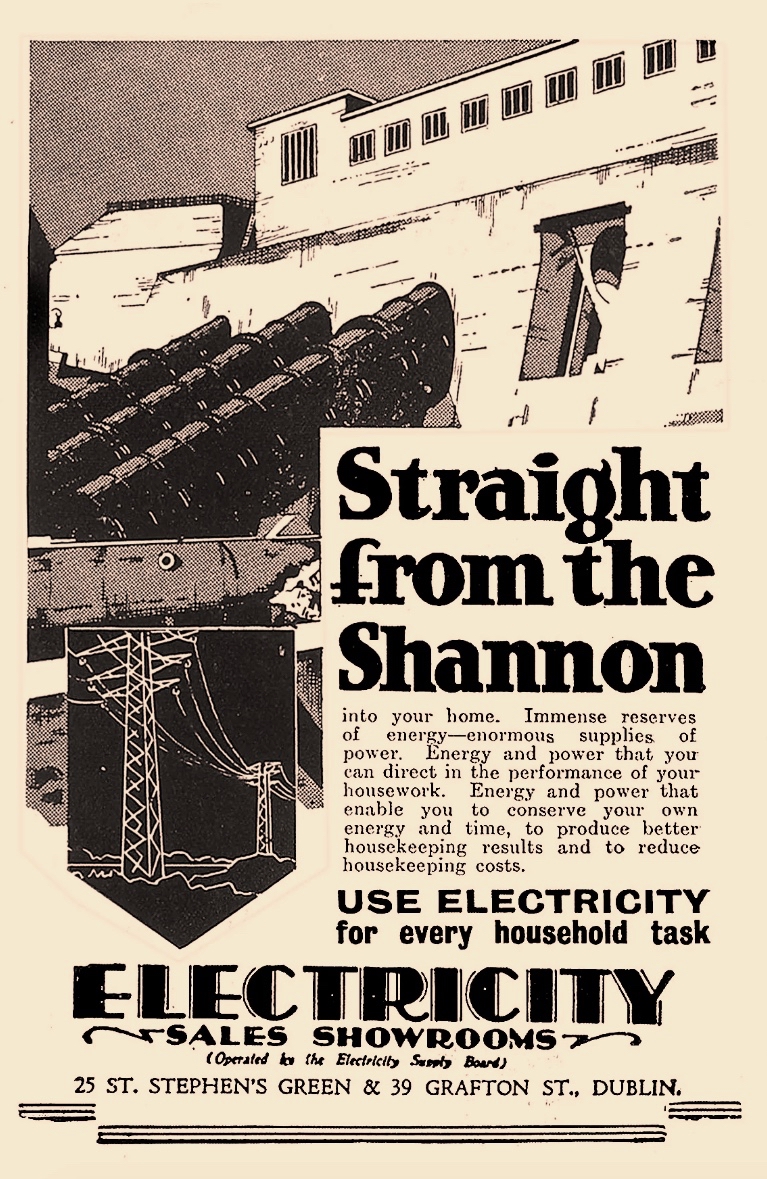

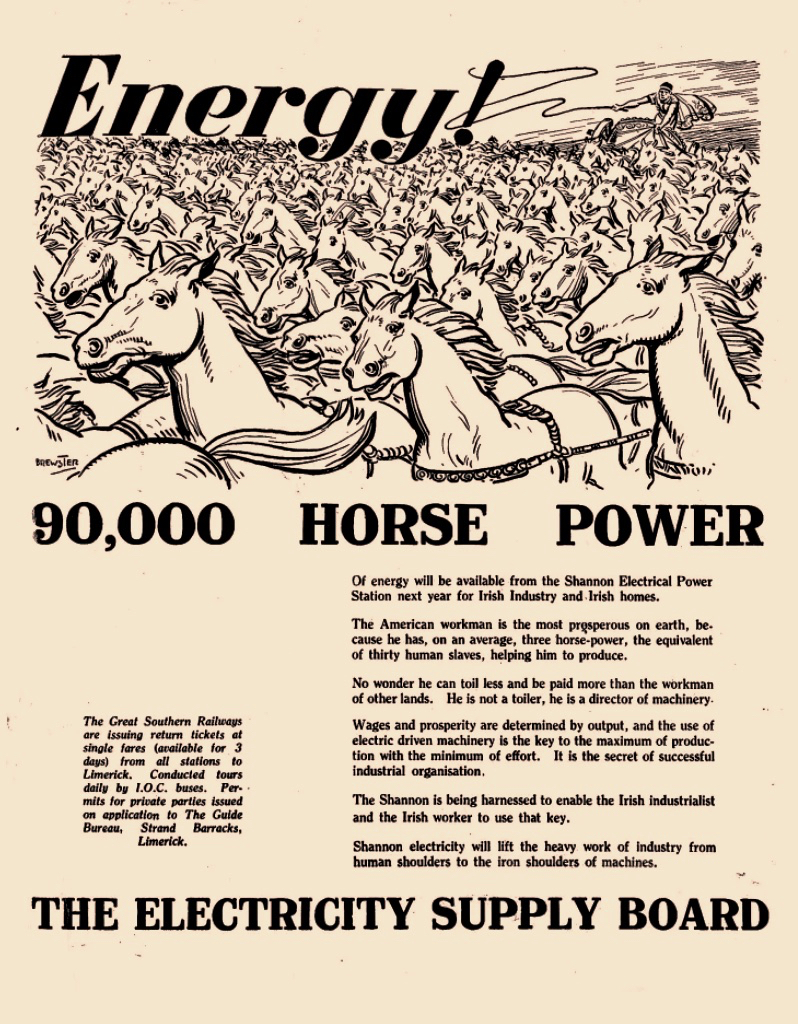

Above – posters from the time of the construction work at Ardnacrusha (ESB Archives). It was certainly the most exciting project in Ireland’s young days, and tourism was encouraged. Hand-in-hand with the major works themselves went a crucial publicity campaign to encourage people to embrace the coming of a readily available electricity supply to homes and businesses. The steps taken to try and ‘get the message across’ was an uphill task. Considerable funds were expended – and a large sales force garnered – to tour the country and persuade the population to buy into the project.

The visuals, humour and underlying psychology of this Ardnacrusha construction-era promotional poster really appeal to me. In case you can’t read the ‘small print’, this is the message that’s being pushed:

. . . 90,000 Horse Power of energy will be available from the Shannon Electrical Power Station next year for Irish Industry and Irish homes . . . The American workman is the most prosperous on earth, because he has, on average, three horse-power, the equivalent of thirty human slaves, helping him to produce. No wonder he can toil less and be paid more than the workman of other lands. He is not a toiler, he is a director of machinery . . .

Post-Famine, America was always seen as the ‘golden land of opportunity’ for Irish emigrants. Now, in 1930, we are being told that Ireland will have the capability to match those fabled fortunes!

. . . Shannon Electricity will lift the heavy work of industry from human shoulders to the iron shoulders of machines . . .

The coming of electricity across Ireland opened up markets for retailers to vend a host of innovative gadgets. This mobile electricity showroom from the 1950s (ESB Archives) covers the gamut of lighting, cooking, refrigerating, water supply to sinks using pumps, milking machines and labour-saving devices for farms. In a future post I want to focus on Rural Electrification, which was a long haul: taking poles and wires out into the extensive hinterland. This was – arguably – the most heroic part of the process of electrification, and we can’t help wondering whether the following somewhat iconic ESB print of the first ‘peg’ being raised at Kilsallaghan, on 5 November 1946 was inspired by the famous Iwo Jima Victory photograph taken by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal on February 23 1945 (lower pic). Both portray a moment of triumph.

Many thanks are due to Michael Barry who referred me to material from the ESB Archives covering our own West Cork areas. Watch out for our commentary on this in a forthcoming post!