It’s a hop and a step from down here on the Mizen (Ireland’s most south-westerly point) up to the top of the island: people are doing it all the time, on foot, by bicycle, by boat… We thought we’d do it as a road trip – in fact, why wouldn’t we circumnavigate the whole of Ireland? We did – it took us three weeks.

Header – the Dark Hedges, Ballymoney, County Antrim, Northern Ireland. Planted by the Stuart family in the eighteenth century to enhance their Georgian mansion of Gracehill, it is now much visited as it features in Game of Thrones. It’s good to know that traffic can no longer go through this avenue, as it has suffered damage in recent times. Above, one of the many byroads that we sought out on our journey around the island: this one is the loop road behind Ben Bulben in County Sligo

It was a most fascinating and educational trip, particularly for me: most of the places I had never visited before. Finola was more familiar with her own country, although for her it was a voyage of rediscovery. In many cases she saw how much had changed over years of boom and bust, while elsewhere her memories were reawakened.

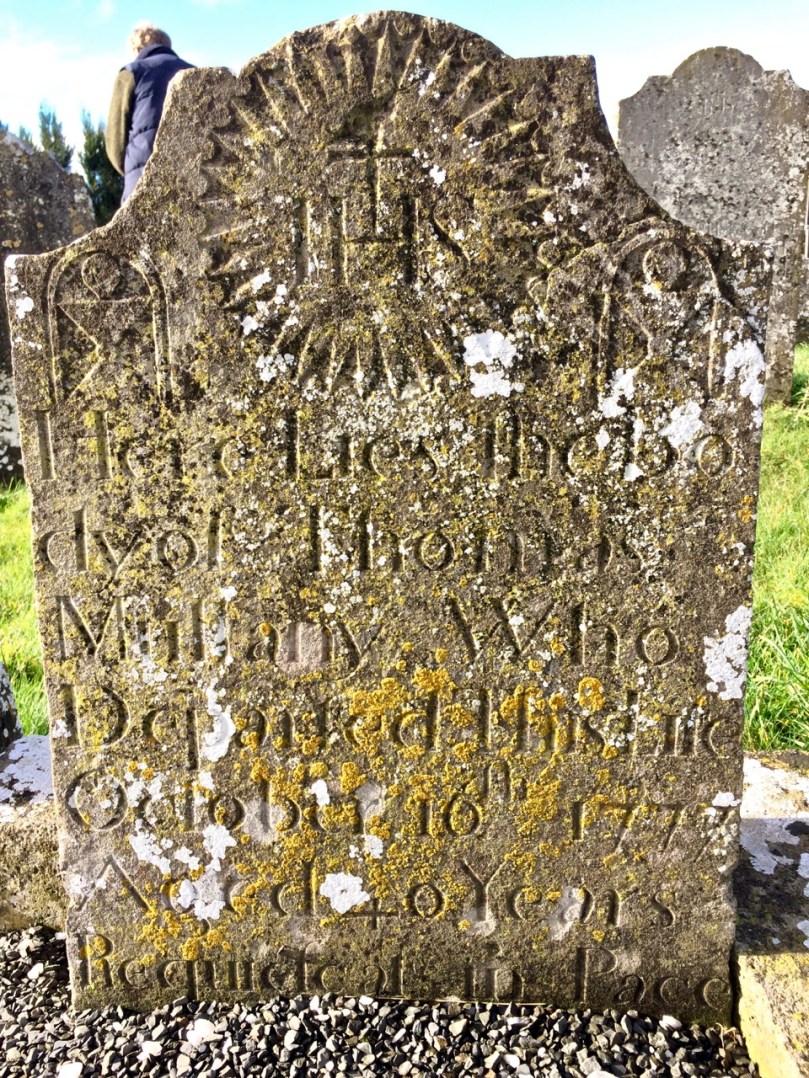

A voyage of rediscovery: Finola’s Great Grandparents are buried here in Killough, County Down, Northern Ireland

This is but a short summary of our travels: a taster. Many of the places we visited will feature in future posts here. As you can imagine, Archaeology, Romanesque architecture, stained glass, saintly shrines, pilgrimage sites, holy wells, stunningly beautiful land- and sea-scapes, and social history were prominent in our must-see itinerary. But we found we were also following in the footsteps of Irish poets. And British eccentrics.

Craftworks: we visited the Belleek Pottery, County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland – which has been operating continuously since 1884 (upper), and (lower) Glebe Mill, Kilcar, County Donegal – where we could watch traditional handweaving on enormous looms

I prefer to stay off the more heavily trafficked tourist spots, but we made exceptions for Europe’s highest sea cliffs at Slieve League, County Donegal (three times the height of the Cliffs of Moher! Beautiful and very wet) and for the Giant’s Causeway. After all, this features strongly in the stories of Finn McCool. I thought that the inevitable crowds were catered for very well and – if you are prepared to walk away from the main site – you can have the spectacular cliff paths largely to yourselves. In Northern Ireland I was very struck by what an asset the National Trust is, for it preserves and makes accessible so many properties and areas of outstanding beauty. If only the Republic had a similar well funded body…

Top – the cliffs at Slieve League. Lower – Giant’s Causeway on a stormy day, and souvenirs in the National Trust’s Causeway Visitor Centre

It would, perhaps, be unreasonable to pick out a ‘best’ destination that we visited, but I must say that I was probably most impressed by the medieval sites: we took in many. It’s amazing that right off the beaten track you can find stunning ancient carvings and artefacts tucked away and – sometimes – not even signposted.

Upper – the superb High Cross at Durrow has been protected and conserved, but it’s not signposted from the busy road that passes nearby. Centre – the beautiful shrine that holds the relic of the True Cross in St Peter’s Church, Drogheda, County Louth: the same church holds the head and remains of Saint Oliver Plunkett. Lower – 13th century font in St Flannan’s Cathedral, Killaloe, County Clare

Our travels were punctuated with a whole variety of experiences, impossible to summarise in one short post. We took in Derry – the only completely walled city in Ireland and one of the finest examples in Europe: we walked the whole length of the early seventeenth century structure. Belfast was intriguing. We undertook the Titanic Experience, and were duly impressed with the building and the exhibitions. We also toured the whole city in the hop-on-hop-off bus: a full two hour tour of everything with a thoroughly enlightening commentary – a good way to keep out of the rain!

Upper – the Peace Bridge in Derry. Lower – the Titanic Experience, Belfast: the exhibition and the building. The external shot is taken from the enormous slipway which was used to launch the ship

We’ve only just got our breath back from all the travelling (although we always went at a leisurely pace with plenty of stops for investigation and coffee). Between us we took well over 5,000 photographs! You’ll see a good few of them in due course.

Often it’s the simple things that impress the most: just little vignettes of Irish life. We would thoroughly recommend a slow exploration of this land – ambling along the byroads and keeping a weather eye open for new experiences. Have a good time!