If you can’t be in West Cork – what’s the next best place? Why – County Wicklow of course! It’s also full of wonderful scenery and imbued with Irish history. That’s Wicklow Town, above, in Viking times: there had already been a Bronze Age settlement on this site. In the twelfth century the Normans arrived, led by Strongbow, who we have encountered before, and Black Castle was built (below). They were wild times, and the castle was attacked and destroyed completely in 1301 by local chieftains, notably O’Byrnes and O’Tooles. There were several subsequent revivals, and the gaunt remains we see today probably date from the 17th century.

While at this site, have a look down at the inlet on the coast to the south: that’s Travelahawk Beach, the scene of a bit of Wicklow history that’s sure to stick in the mind. It was there that St Patrick first landed in Ireland!

I have to admit that the beach is only one of several sites on the east coast that lays claim to this historic occasion, but I like the associated story of Travelahawk which tells how the local people, suspicious of this stranger, threw rocks at St Patrick and his crew. One of them hit the saint’s companion, and he lost his front teeth. He was known ever after as ‘Gubby’ or ‘Gap-toothed’ which is translated in Irish Mhantáin. Hence the old name for Wicklow is ‘Chill Mhantáin’ – the Church of Gubby. Today’s name for the town, Wicklow, is of Viking origin, and means ‘Bay of the Meadows’.

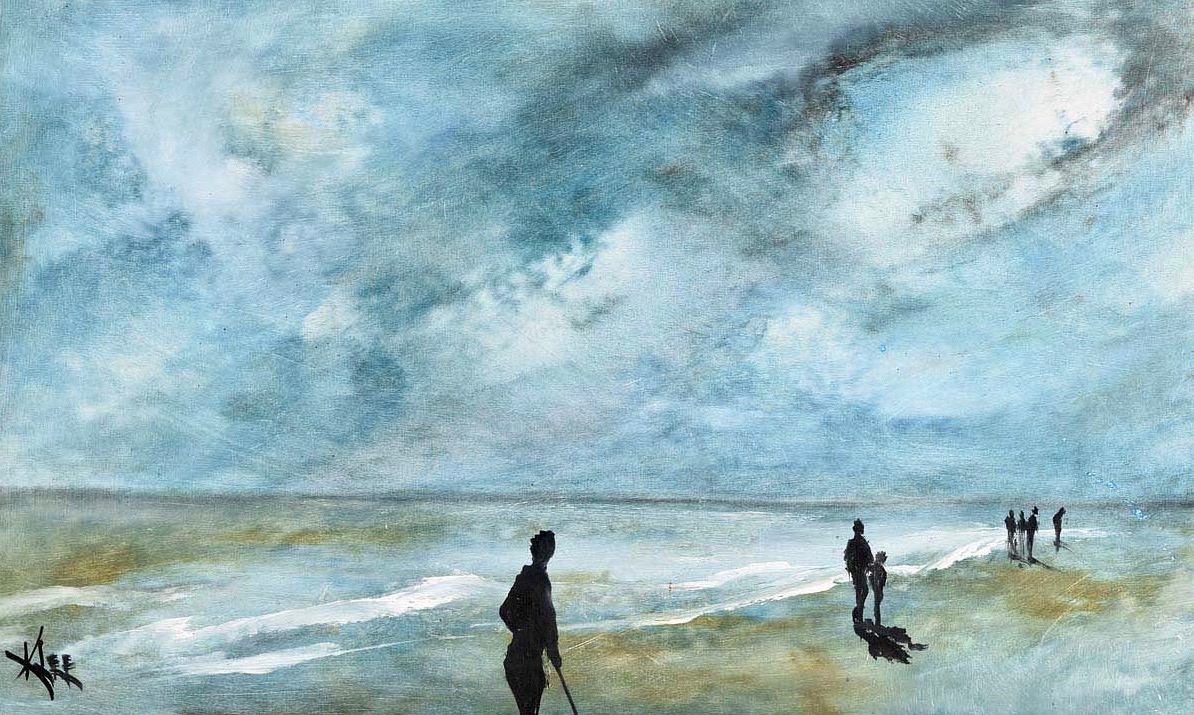

We popped over to Wicklow on a mild February day for a change of scene – and to absent ourselves from Nead an Iolair while some upgrading works were taking place. I was impressed: I had never explored the town before. Finola, however, was brought up in County Wicklow, and her impressions of the county town today were embellished with memories of times past. There’s much about the place that’s picturesque: I was taken with the number of painted murals about the place. The pier has, appropriately, a whole series of ships on the breakwater wall. There is an example, above . . .

. . . And here’s another. In fact, this one is the 50th mural to be painted by Pat Davis, who is the local postman. Each one depicts a vessel which has visited the harbour. It’s a wonderful and colourful record of one aspect of the maritime town’s history.

Here’s Pat at work. The image is courtesy of Ceaneacht O Hoctun, and appeared in the Wicklow People newspaper in 2020. Pat started painting the ships in the 1970s.

This one will be familiar to West Cork folk. It’s the Saoirse, a 42ft ketch built in Baltimore in 1922 for her designer, Conor O’Brien.

. . . This unique sailing ship was also a maritime inspiration for the new Ireland, uncertain of itself in an uncertain world. For this was Conor O’Brien’s characterful 42ft ketch Saoirse, which he designed himself, and with which – between 1923 and 1925 – he pioneered the round the world route south of the Great Capes, an ocean voyaging “first” which was forever written into world sailing history. . .

Afloat.ie

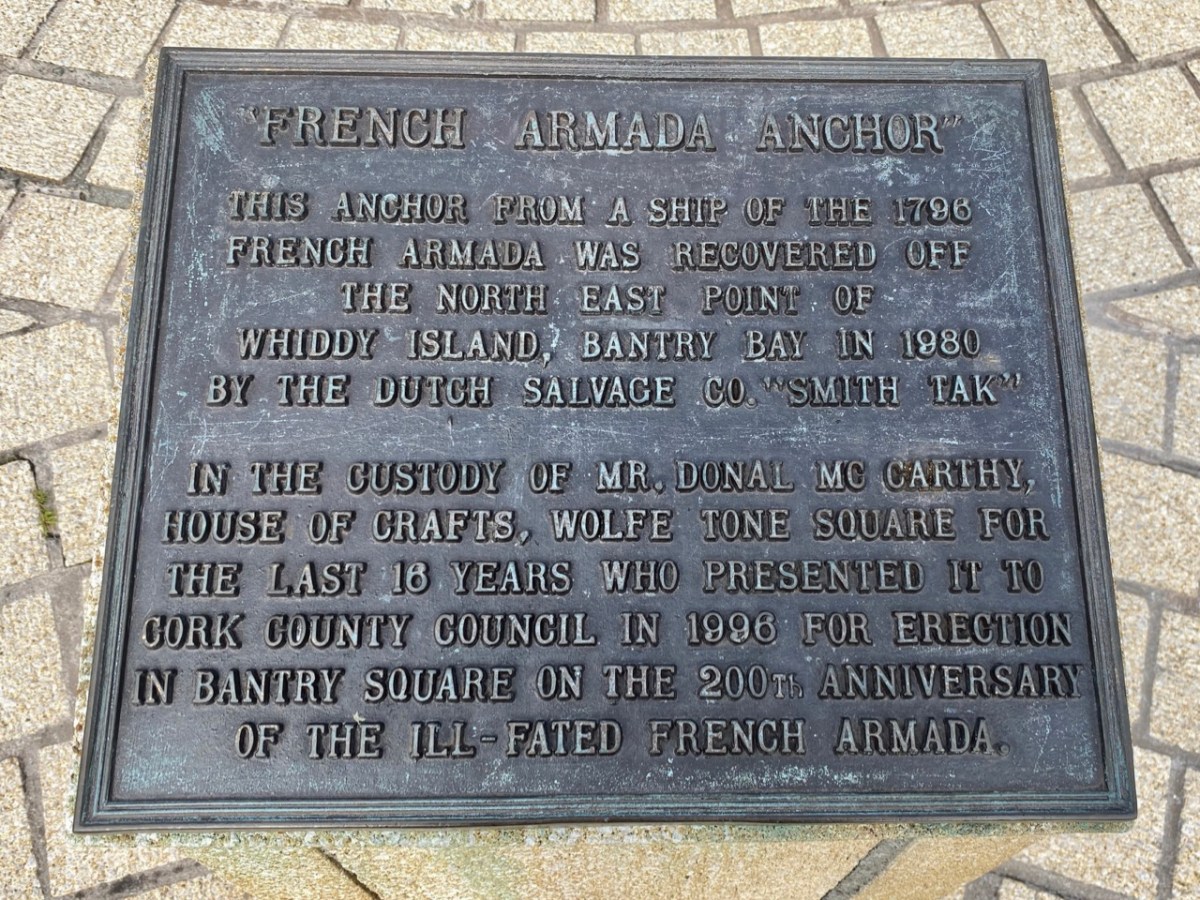

When O’Brien returned from his record-breaking voyage in 1925 he made his first landfall in Ireland in Wicklow Harbour. O’Brien designed a larger version of Saoirse to be the inter-islands communications vessel for the Falkland Islands: this – the Ilen – was also built in Baltimore. Back in 2015 we visited Oldcourt boatyard on the Ilen River to see the restoration of the larger ketch, which was then underway. That work was completed in 2018, and the same team embarked on a complete rebuilding of Saoirse, which had been wrecked in Jamaica in 1979. Our own West Cork photographer, Kevin O’Farrell has beautifully documented these projects at Oldcourt in his book, published in 2020.

The Asgard, above, was famous for gun-running at Howth by Irish Volunteers in 1914. Below is an Irish Navy vessel, LÉ Gráinne – a mine sweeper. Gráinne was a legendary princess who was promised to Fionn Mac Cumhail but ran away with his young follower Diarmuid. The ship was decommissioned in 1987.

We found that the town of Wicklow has so many maritime associations – everywhere you look there are reminders. But also it’s a thriving commercial centre and we were impressed by what is on offer there: great eateries, and a most wonderful bookshop. I think there might be another post in the making . . .