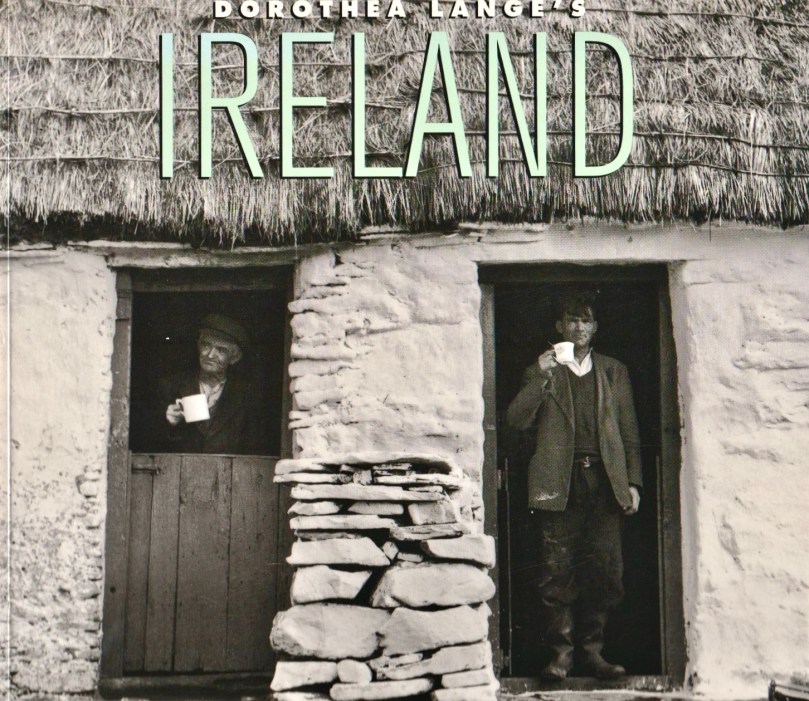

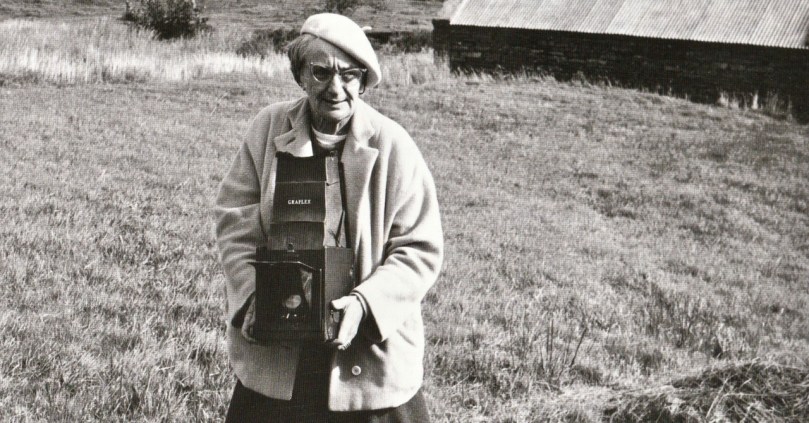

This post complements last week’s overview of the work of Dorothea Lange, who spent several weeks in County Clare in 1954, documenting the rural way of life she observed there in over 2,400 monochrome photographs. That’s a monumental collection which can only be fully accessed by visiting the Oakland Museum of California. We are fortunate to have a book of some of her Irish work – Dorothea Lange’s Ireland – published by Eliott & Clark, Washington, 1996 and a current exhibition which includes some of her images at Dublin’s Museum of Decorative Arts & History, Collins Barracks. That same exhibition features the work of two further documentary photographers, one of whom is our subject today: Robert Cresswell (below):

The Paris-based American anthropologist Robert Cresswell (1922-2016) remained on in France after WWII, having served in the US army there for four years. Following the completion of his studies in anthropology in Paris, he arrived in Ireland in 1955 with the ambition of carrying out an anthropological analysis of an Irish rural community. Taking the advice of the Irish Folklore Commission he chose Kinvara, County Galway. The small rural town of Kinvara and its agricultural hinterland would become the base for his study, published in 1969 as ‘Une Communauté Rurale de l’Irlande’ . . .

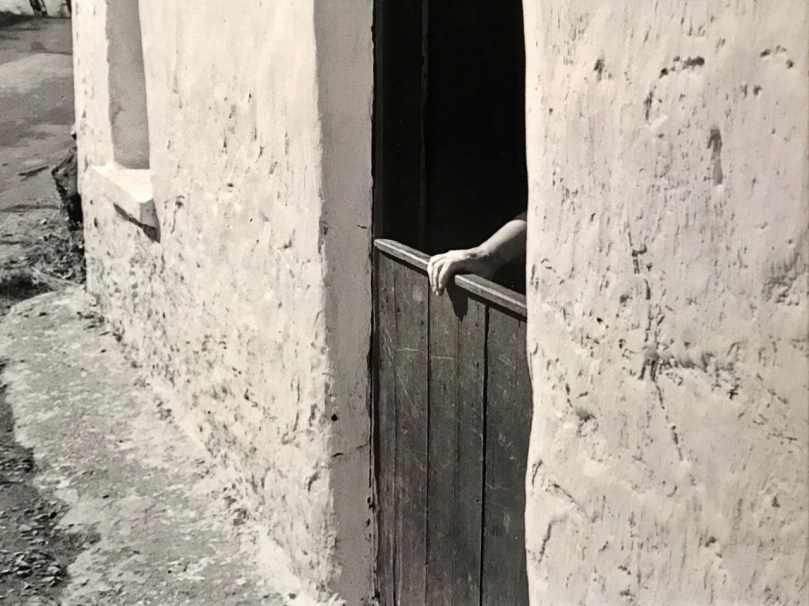

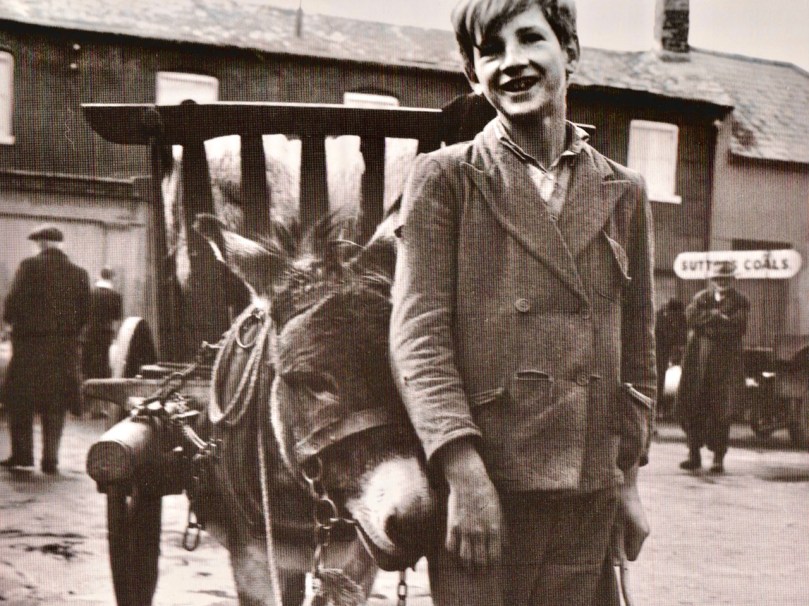

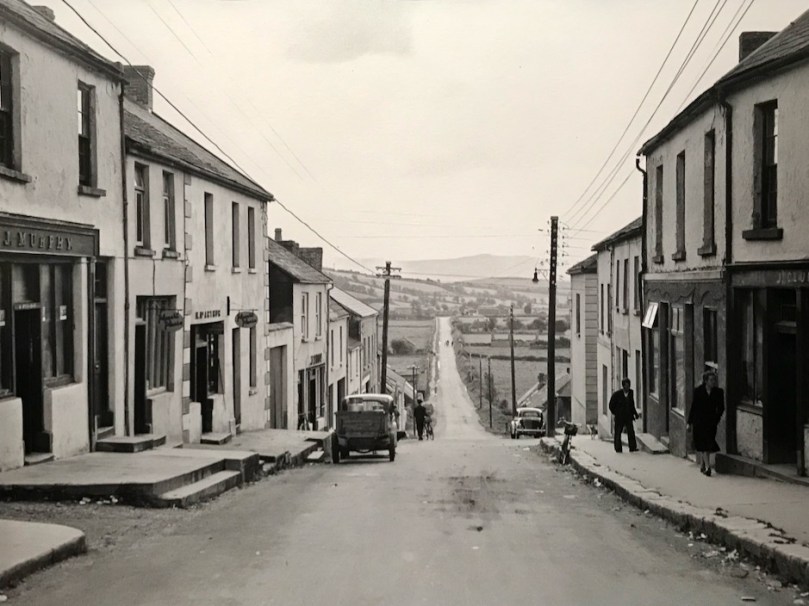

Header – Kinvara on Fair Day, 1955 by Robert Cresswell. Above – Kinvara, Co Galway, streetscape; compare these to Dorothea Lange’s views of Ennis and Tulla, Co Clare (in last week’s post), taken in the same period

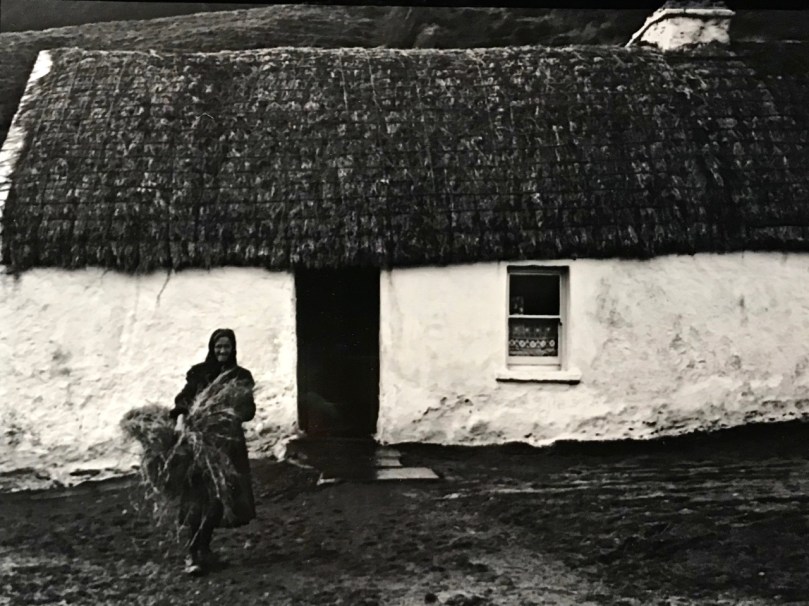

While the photographic essays by Dorothea Lange and Robert Cresswell bear close comparison – and how hugely interesting it is for us to see Irish rural life through those lenses nearly 70 years ago – it’s fascinating to consider that both came from very different backgrounds and disciplines, but were equally absorbed by the iconic images each of them was capturing – giving us a visual ‘time capsule’ of Ireland as it was apparent a few generations ago.

Above – examples from the Dublin exhibition showing the work of Cresswell taken from his colour slides

Robert Cresswell was a pioneer in some respects, in that he used Kodachrome film to produce colour slides, in the days when monochrome documentary photography was the norm. Some professional photographers could not cope with the idea of using colour, partly because they considered the images were not realistic. Ansell Adams felt that ‘. . . color could be distracting, and could therefore divert the artist’s attention away from creating a photograph to its full potential . . .’ while Henri Cartier-Bresson famously uttered his opinion that ‘. . . color is bullshit . . .’ – which was all he ever said about it, allegedly! My own (humble) opinion is that there is something about monochrome photographs which seems to draw the eye and enhance the atmosphere, particularly with historic images. I can’t explain this – there is no logic: it’s just a personal response which I am always aware of.

Above – monochrome Kinvara: the Forge, and Corpus Christie procession

Robert Cresswell lived in the Kinvara community for fifteen months between 1955 and 1956, returning for short periods in 1957 and 1958. The quotations in this post are from the exhibition text panels:

Capturing more than five hundred images . . . Cresswell photographed the people of Kinvara, their countryside, their work on sea, shore and land, the daily lives, religious processions, and fairs and markets. Documenting the changes that were occurring in the shift from a traditional farming community to a wider market-led economy, he was motivated to emphasise a community in transition over one operating in the continuity or stagnation of tradition. His photographs generally portray a well-functioning society, but his interpretation of emigration as the ultimate destructive agent in community and country profoundly influenced his understanding of rural life in a small community in 1950s Ireland . . . The population of the parish of Kinvara sustained a net loss of 80% between 1841 and 1956 . . .

Above: a community in transition – contrasting pictures of family life in Kinvara recorded by Cresswell in the mid 1950s

Tempting though it is to show you much more of Cresswell’s work here, I really want you to go and see for yourselves. The exhibition at Collins Barracks, Dublin continues until April this year, and is well worth making the effort to visit. Robert Cresswell lived a long life; in 2010, then aged 88, he donated his entire collection of documentary photographs and cine film of Kinvara to the Irish nation. He waived his own copyright to this unique work in favour of all persons who wish to use any of it for educational or heritage purposes (but not for commercial gain without prior permission). Copyright now rests with Kinvara Community Council, who have published an excellent website here. I have used a small number of images from the collection to supplement those we found at the exhibition, in order to give you a fair cross-section of the entirety of Cresswell’s opus.

In a mirror of present-day events in Ireland, here’s a shot by Cresswell of the Sinn Fein candidate Murchadh Mac Ualtair canvassing in Kinvara for the 1957 General Election with Peggy Linnane. In that election Fianna Fáil, under Éamon de Valera, took 78 seats with 48.3% of first preference votes, and Sinn Féin took 4 seats with 5.3% of first preference votes. In our 2020 election, just passed, Sinn Féin, under Mary-Lou McDonald, took 37 seats with 24.5% of first preference votes in a thoroughly divided result, leaving us all in a bit of a dilemma! But I digress . . .

Another of Cresswell’s colour images, showing the killing of the pig – a family affair

There is one more photographer in this exhibition, who I will feature in a future post – watch this space! One last image from Robert Cresswell, possibly another view of the Corpus Christie parade: