The great passage tombs of the Boyne Valley complex in Co Meath – Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth – have been known and celebrated (although not necessarily understood) by antiquarians over many centuries. Here’s an early survey plan of Newgrange drawn by Thomas Molyneux of Dublin in 1700:

The Boyne Valley monuments are famous for their megalithic art – inscribed stones which are integral to the structures, carved some 5,000 years ago. The drawing above shows the carved stones in the great passage which we now know is aligned to the sunrise at the winter solstice. Although quite crudely depicted, these are the earliest representational images we have of passage tomb art in Ireland. A century and a half later the surveyor and antiquarian George Victor du Noyer worked with the newly established Geological Survey of Ireland and became fascinated with the megalithic art of the Loughcrew Passage Tombs in Co Meath. His recording of this, using watercolour sketches, is remarkably accurate:

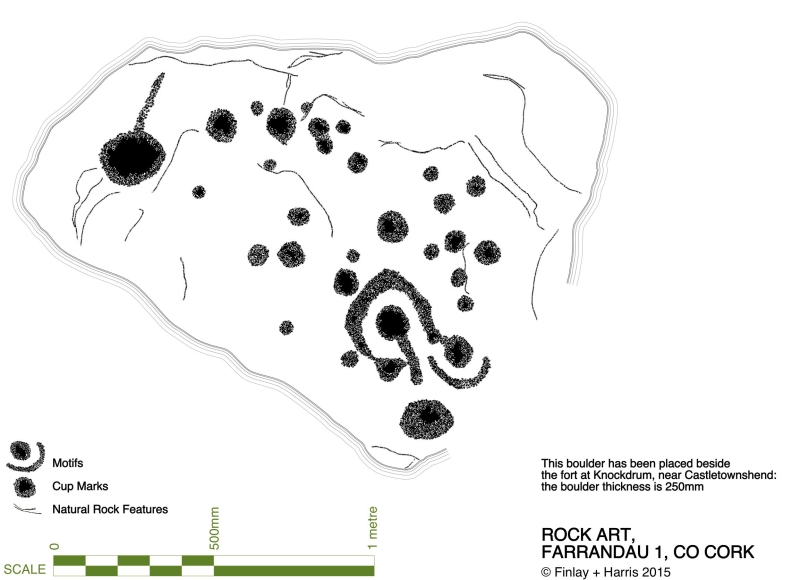

Another century on, and archaeology – and the recording of ‘ancient’ art – had increased in sophistication. Finola’s work in the 1970s used a combination of direct tracing and photography, and her opus is still one of the most comprehensive and striking collections of images of Prehistoric Rock Art. These differ from Passage Grave Art both in the motifs and the overall design of panels, but are thought to be of comparable age. Here is one of her images, of rock art at Rathruane More in West Cork:

Today’s post focusses on a site which was first noted in 1905 but not categorised or fully explored until the 1980s, when Professor Muiris O’Sullivan of UCD led a detailed excavation, over many years. The report in excavations.ie states:

. . . Knockroe is one of a small number of decorated sites outside of County Meath, and in the overall context of Irish passage tombs its megalithic art is very important. Only a few of the kerbstones are visible but they bear a profusion of kerb ornament which is matched only at the three great tumuli in the Boyne Valley. One of the decorated stones in the western chamber bears a remarkable likeness to the designs at Gavrinis in Brittany, France . . .

To find this gem (known locally as The Giant’s Grave – Finola’s post today describes another one!), you have to turn off the M8 at Cahir, and follow the N24 and N76 towards Ninemilehouse. If this sounds familiar, it’s because we also followed this route when we visited the Killamery High Cross, but this time turn before Ninemilehouse, at Garranbeg, and cross over the River Linguan, then follow the river to the County border (Tipperary / Kilkenny) where you will see signs to Knockroe Passage Tomb and Knockroe Slate Quarries. After your visit it’s easy to join the M9 at Knocktopher and carry on up to Dublin. It will add a little more than half an hour to the journey (plus the many hours you might want to spend exploring the fascinating passage tomb).

The aerial view might help to orientate you, while the 25″ OS map extract (above) dates from the late 1800s and shows the extent of the nearby Victoria Slate Quarry workings then. Slate was evidently taken from this site as early as the 14th century. In the aerial view it is possible to make out a distinct trackway which passes over the centre of the now identified passage tomb. This is clear to see on the site, and at either end the track continues, and is defined by ancient-seeming hedgebanks and established trees :

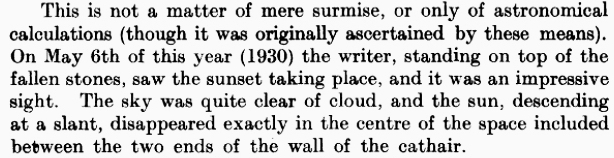

Tradition has it that the trackway was provided in the nineteenth century by the owners of the nearby Victoria Quarry to allow cattle to access the river when the quarry workings encroached on previous routes. A plan of the passage tomb is shown on the site notice board, and I have marked on it the laneway. This clearly shows the layout of the Neolithic monument, which would have been covered with an artificial mound, enclosing the two chambers. As with the larger monuments in the Boyne Valley – Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth – stones in the passage chambers and some of the kerbs are decorated, and the chambers themselves have solar alignments, reportedly with sunrise (east) and sunset (west) on the winter solstice.

As yet we have not been to Knockroe at the winter solstice – it’s something we would like to do. We have attended the solstice celebration at our own West Cork site, Drombeg Stone Circle, and that is a great community experience. But Pete Smith has provided this fascinating visual record of the Knockroe Solstice recorded in 2016. Thank you, Pete!

But let’s turn our attention to the art at Knockroe. It’s what makes it so special. It’s not as spectacular as the larger examples in the Boyne Valley or Loughcrew (you might think of Knockroe as a ‘country cousin’) – but it is their equal in its scope and variety. And – what we really liked – you can have the place all to yourself! There is no visitor centre, no queueing or paying – nothing to spoil the ambience. It is always freely accessible, and we didn’t see a soul while we were there. It is, of course, merely a skeleton of what it once was – five thousand years ago – but that doesn’t detract from its allure. It’s a place imbued with things we don’t understand, or can only guess at – left behind for us by our distant ancestors. And, hopefully, we will keep it safe for the future.

Muiris O’Sullivan penned a comprehensive article in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Vol 117, 1987 – The Art of the Passage Tomb at Knockroe, County Kilkenny. This is well illustrated with drawings by Ursula Mattenberger based on rubbings taken directly from the stones. Here is her impression of Stone 8 (numbering from the excavation report), which is directly facing us in the photograph above:

This example is very unusual in the corpus of passage grave art in Ireland. But it bears a resemblance to examples on the island of Gavrinis, in the Gulf of Morbihan, on the southern coast of Brittany, France. This has been noted by several commentators, including Muiris O’Sullivan, and the suggestion has been made that the tomb builders at Knockroe could have been directly influenced by the Gavrinis examples (which are generally thought to be earlier than the Irish parallels). It has even been suggested that passage tomb builders travelled from one site to another (like the medieval cathedral builders), and that this comparison demonstrates this. Have a look at these images from Gavrinis and see what you think (the first is courtesy of Martin Brennan, taken from his The Stars and The Stones, Ancient Art and Astronomy in Ireland, Thames and Hudson 1983):

The excavation of Knockroe involved the removal of earth and debris from the collapsed mound which would have covered the tomb originally. This clearance revealed more of the art and here is an interesting comparison which shows the evolving history of the site. Firstly, our recent photograph of Stone 12, followed by the excavation record of this stone (lower right of the drawing) from the 1980s:

Here is our photograph again, with some of the art from the drawing above superimposed. It’s clear that the full extent of the artwork on Stone 12 was not visible below the red line when the drawing was made: Muiris O’Sullivan notes in his reports that he was aware that some of the art was hidden below what was then ground level.

Ursula Mattenberger’s drawing above also illustrates Rock 5 (upper left) and shows the very distinctive ‘rosette’ motif of six cup-marks. Examples of this motif have been found at rock art sites – including the one on Finola’s drawing of Rathruane More, nearer the top of this post. Here’s a photograph of the Knockroe example:

While making comparisons with rock art (and remembering that passage grave art and rock art are distinctive categories), here’s another decorated slab at Knockroe, not entirely legible in its weathered state. It seems to show a number of incomplete cup-and-ring motifs but in its own right this is known as a horseshoe motif. Below it is another of Finola’s drawings from 1973, perhaps showing something similar at Coomasaharn, Co Kerry:

The Knockroe site is endlessly fascinating. O’Sullivan’s excavations revealed a quantity of smaller quartz boulders which appear to have collapsed from a possible quartz facing reminiscent of Professor O’Kelly’s reconstruction of the Newgrange mound (image below by Tjp Finn via Creative Commons):

Hopefully I have given you enough here to whet your appetite and lead you off the motorway to explore the exceptional remains at Knockroe, Co Kilkenny and, in particular, its remarkable examples of passage grave art.