There is no firm line that denotes where our most south-westerly Irish peninsula begins. Our series, Mizen Magic, has reported on walks, roads, views, history and archaeology which can definitely be defined as belonging to the Mizen (which we tend to think of as being to the west of, and including, its ‘gateway’ – Ballydehob). Perhaps we should start a series titled Magic Beyond The Mizen – in which case this would be the first: a report on a very prominent site about half an hour’s drive along the coast east of where we live: a historic structure – built within the last 2,000 years – but which contains evidence of much older human activity.

Here is an overhead view – the best way to see and understand the layout and construction of Knockdrum Stone Fort, which occupies a superb hilltop location in the townland of Farrandau between Skibbereen and Castletownshend. Thank you, Dennis Horgan – our professional West Cork aerial photographer – for allowing us to use this image: have a look at his website for other examples of his work, and for details of his excellent photographs and books.

The Fort is located on a high ridge (although not on the summit of the ridge) with far-reaching views both inland and to the south, over the sea. The header picture looks from the Fort out to the west over Castlehaven to Galley Head in the far distance; the view in the picture above is due south – looking towards Horse Island, and the stone wall of the Fort is in the foreground. From these breathtaking vistas it’s reasonable to conjecture that Knockdrum Fort has a strategic siting, providing views of anyone approaching from the sea, and able to signal their arrival to dwellers in the ‘interior’ – the lands to the north. We cannot know for sure that stone fort structures had this – or any other – specific purpose: many theories have been advanced. Comparison with other examples is worthwhile. One of the largest stone forts in Ireland is Staigue Fort, near Sneem in County Kerry.

Staigue Fort (above) has a diameter of 27.5 metres, the present wall height is 5.5 metres, and the wall thickness is 4 metres. At Knockdrum the diameter is 22.5 metres, the present wall height is 2 metres and the wall thickness around 3 metres. The Duchas information board at Staigue says:

. . . This is one of the largest and finest stone forts in Ireland and was probably built in the early centuries AD before Christianity came to Ireland. It must have been the home of a very wealthy landowner or chieftain who had a great need for security . . . The fort was the home of the chieftain’s family, guards and servants, and would have been full of houses, out-buildings, and possibly tents or other temporary structures. No buildings survive today . . .

The picture above shows the present interior of Knockdrum Fort: the stone walls are likely to delineate a former building here. In the corner of the inner stone enclosure is the entrance to a ‘souterrain’ – a series of underground passageways. The souterrain is outlined on the following drawing of the Stone Fort which was made in 1930 after a detailed investigation of it by Vice Admiral Henry Boyle Somerville, the younger brother of writer and artist Edith Somerville of Castletownshend. Boyle, his life and his tragic death, is the subject of Finola’s complementary post today.

Finola is also discussing Boyle Somerville’s interest in the alignments of archaeological structures. In Boyle’s paper for The Journal of The Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 1931 (title page below), he presents the evidence that this Fort is on a solar alignment.

Boyle sets out the case for an alignment based on the Knockdrum Fort:

. . . This conception of the earlier use of the site of the cathair [the stone fort] for purposes which may perhaps be termed “religious,” seems to be borne out by the following fact. At a horizontal distance of about 600 yards to the E.S.E of the cathair, and at 210′ difference of level below it, there is a small rocky ridge standing up from the surrounding grass land. The name of the ridge is “Peakeen Cnoc Dromin,” The little peak of the white-backed hill . . .

The following paragraphs and photos are from the Journal paper:

Finola and I are familiar with the Peakeen Cnoc Dromin from our researches into Rock Art: the uppermost stone (which does appear similar to the capstone of a fallen dolmen) is heavily cupmarked. The photos of the Peakeen (above) were taken before we had any idea that they might form an alignment connected with Knockdrum Stone Fort. We will have to revisit again at Bealltaine. Boyle confirmed his alignment theory by personal observation:

He went on to suggest:

. . . It is one of the clearest instances of intentional orientation between two ancient, and artificially formed monuments that can be imagined . . .

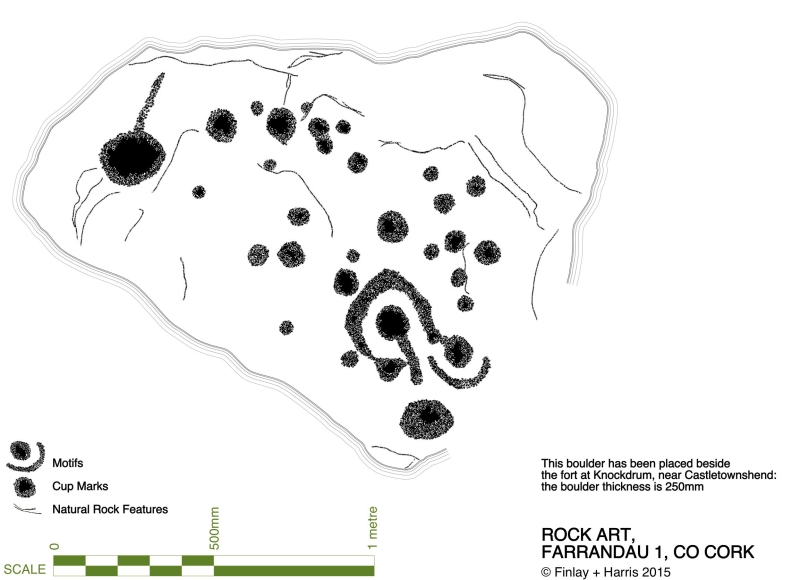

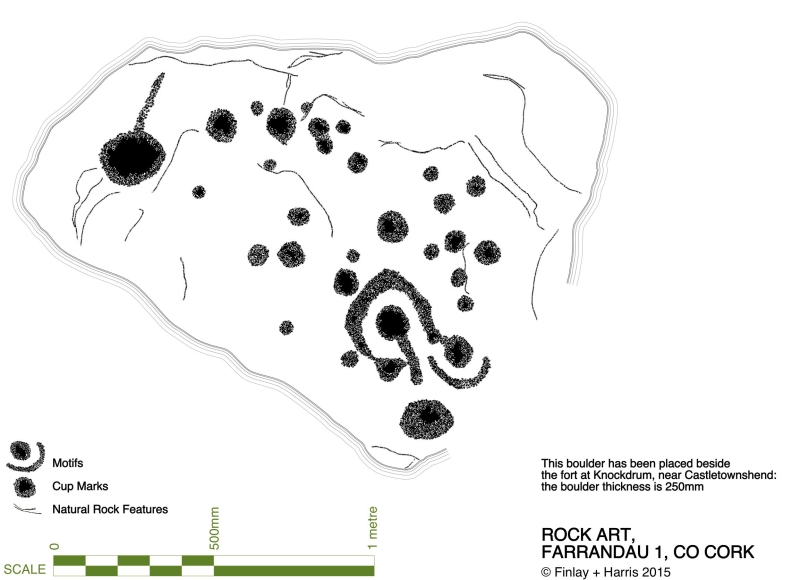

Of course, it can’t be the case that a cupmarked stone dating from anywhere between 3,000 to 5,000 years ago was in any way connected with a stone fort that dates from the early part of the first millennium AD. However, I have as yet omitted an important piece of information: at Knockdrum Fort, high up on the hill, are two further ancient cupmarked stones – and significant ones: the larger also exhibits Rock Art. Somerville illustrated them in 1930, and Finola recorded them in detail in 1973.

Images above are of the stones recorded at Knockdrum: topmost is Boyle’s drawing from 1930. Below Finola’s drawings are photographs of the large stone lying by the Fort entrance today: it is known that this has been moved, possibly during Somerville’s time. The old photograph immediately above is from the Coghill Family Archive and shows Arthur Townshend beside the stone, which is standing. Arthur was born in 1863: this photograph may record the occasion of the expedition by the young Somervilles and ‘their cousin’ (quite possibly Arthur) to Knockdrum described below, which took place in 1875. It is the presence of Rock Art and cupmarks at the Fort itself which tells us that the site must have had significance in far earlier times (perhaps that’s why the fort was sited in that location – rather than on the summit of the ridge), and Boyle’s reported alignment would have been with the carved rocks (or the important location that they marked) rather than with the comparatively modern stone fort.

The souterrain in the enclosure of Knockdrum Fort (entrance in top photograph – ‘chimney’ in lower photograph) was explored in 1875, as Boyle recounts:

The ‘band of three youthful archaeologists’ are likely to have been Somervilles: Edith (the eldest, then 17), Boyle (then 12 – it was he who was lowered down into the discovered ‘cave’ by his ankles!) and, probably, a cousin. Great adventures, which would undoubtedly raise eyebrows today.

Within the fort enclosure is this cross-marked stone. It was apparently leaning against the wall in Boyle’s days, but has now been embedded close to the entrance. We visit this site often: this time we noted some significant disruption to the upper level of the dry stone walling, possibly caused by the fierce storm winds earlier this year. Compare the detail below with Dennis Horgan’s aerial view above, taken a few years ago.

Some damage has also been suffered to retaining walls on the green boreen leading to the Fort from the main Skibereen – Castletownshend road (a walking route only), and on the stone walls beside the 99 steps which take you from the green path to the top of the hill. These are passable with care, but it is hoped that this monument – which is in State ownership – will be deservedly returned to good order before too long: it is one of the historic wonders of West Cork.

Email link is under 'more' button.