It certainly does! But this post is – literally – about rock: the hard, knobbly kind that is underneath us, surrounds us, and which has historically built our environment. In the picture above, taken on a clear February day during the most severe Covid lockdown, Finola is walking through beautiful West Cork. Beyond her is the great, gaunt outcrop of Mount Gabriel. Beside her is a traditional stone wall: its design unchanged over centuries. In the landscape all around her are rocks – large and small – scattered in the rough pasture.

In the distance, of course, is the coast: there are very few places in West Cork where you cannot, at least, catch a glimpse of the sea – and so many where you can immerse yourself in it, or stand on its shore and admire the infinite textures which those same rocks display. It’s mostly Old Red Sandstone: that’s the correct geological term. It was laid down in the Devonian period – a while ago now: between 400 and 300 million years, in fact. This followed an era during which our mountains were built, known as the Silurian times. Continents were shifting and separating, and what was to become Ireland was a great arid desert – deserted: there was no-one around to see it!

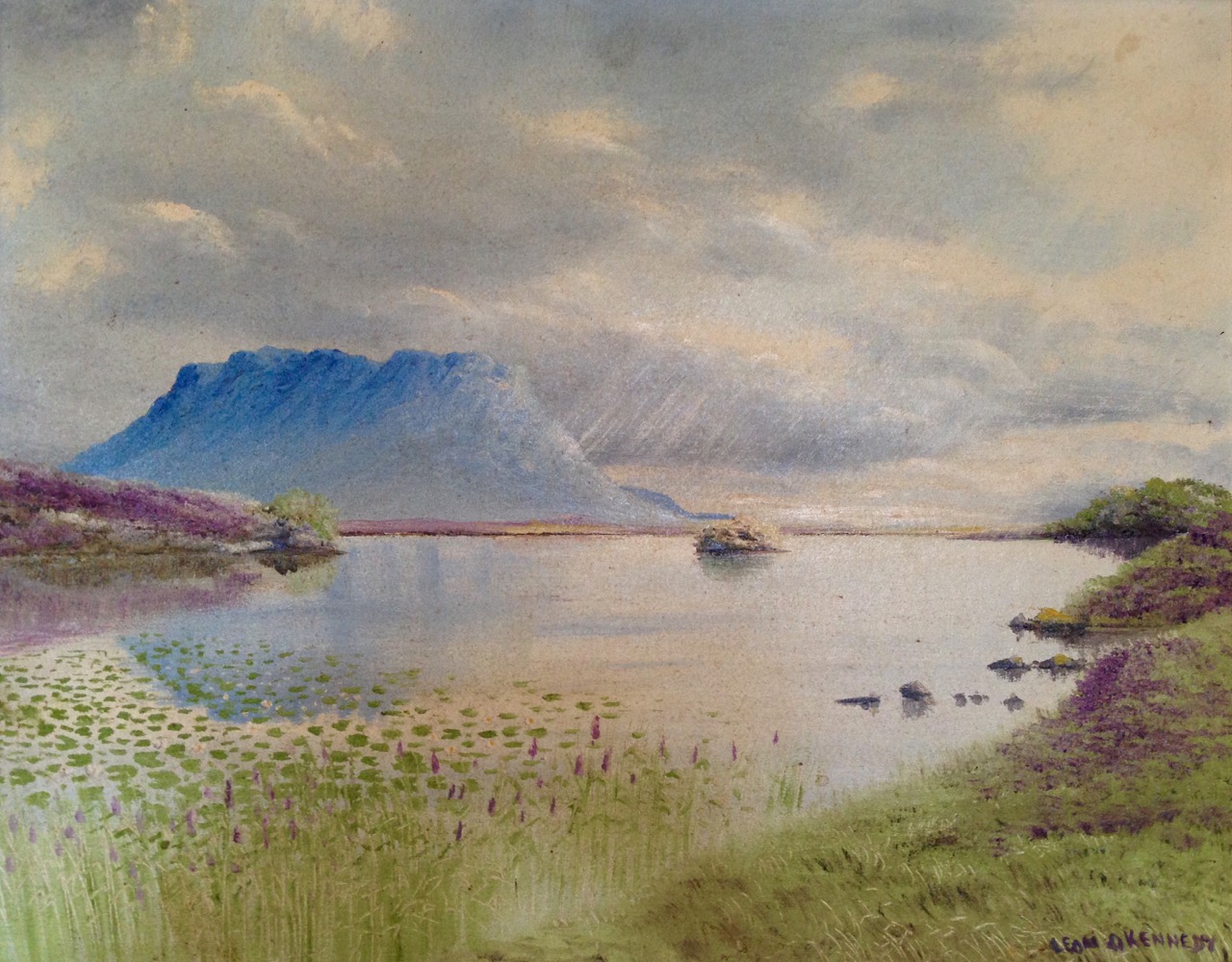

Old Red Sandstone: in fact it varies in colour depending on its local history. Broadly, some of the mountain rocks are purple-grey, while those closer to the sea could be greeny-red, but that is probably far too wide a generalisation. The sheer beauty is in the infinite shapes and colours. What artist needs any finer palette?

In those deserted times, an ‘Old Red Sandstone Continent’ extended over what is now northwest Europe, but it is worth noting that in ‘our’ part of it – the Munster Basin, covering today’s Kerry and Cork – we have one of the densest masses of this rock in the world: at least 6 kilometres thick. And we have to appreciate what it has given to us – high mountain spines sweeping steeply down to an indented shoreline of coves, creeks and inlets, with the myriad mottled islands that we oversee. An unparalleled, unfolded world.

After the ‘desert’ period, but much later – only about a million and a half years ago – came the Pleistocene Epoch. the word is from the Greek polys and cene – meaning ‘most recent’ – and that brings us almost up to date. That was a time of great climate events: deserts were inundated and then covered in ice sheets 3 kilometres thick, while moving glaciers tore up the rock surfaces, advancing and retreating several times. Eventually, what had been desert became arctic tundra. It is supposed that the ancestors of our present day life forms happened along during this epoch, and managed to survive. But we don’t find any traces of them until after the last ice sheet retreated in our part of the world – only about 12,000 years ago. The landscape that was left behind was inundated by rising sea levels, and the very last land bridge (between Cornwall and the eastern tip of Wexford) was washed away after that, but not before the Giant Elk and its mammal relations had got a foothold on the western side. The snakes, however, didn’t make it. And what of the humans?

Well, the humans embraced the rocky landscape. They made their marks on the outcrops; then they moved the rocks about, and made architecture from them. We can still see their efforts, some 5,000 years later.

These Neolithic carved motifs could be the earliest human interventions on the natural Irish landscape: they might date from 3,000 BC. These examples are from West Cork, and were only discovered a few years ago. Finola wrote the definitive thesis on Rock Art when she studied at UCC in the 1970s, and we have staged exhibitions and given talks on the topic.

A couple of thousand years later, Irish people started to build things with the stones they found around them. This wedge tomb under the backdrop textures of Mount Gabriel at Ratooragh has rested here since the Bronze Age. Finola’s post today uncovers the fascinating folklore stories that generations have told about such artefacts. But restlessly working the fabric of the landscape – Old Red Sandstone – into walls, shelters, tower houses, temples and towns has never ceased.