The sixteenth century was a desperate time in Munster. Two successive Desmond Rebellions (read about them here and here) had resulted in a devastated countryside where, according to the Annals of the Four Masters the lowing of a cow, or the whistle of the ploughboy, could scarcely be heard from Dunquinn to Cashel in Munster. The power of the FitzGeralds, Lords of Desmond, and their allies among the Gaelic chieftains, had been broken.

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, unknown artist, oil on panel, after 1572, NPG 715 © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used under license

The Tudor government determined that what was needed was a complete colonising effort, that would bring the benefits of English civilisation to the lawless Irish. William Cecil, Lord Burleigh, set about planning the Plantation of Munster.

In June 1584, a commission surveyed southwest Munster, mapping out the lands belonging to a swathe of Irish lords associated with the rebellion, which were then granted to a small group of wealthy English Undertakers.

John Dorney: The Munster Plantation and the MacCarthys, 1583-1597

Jobson’s dedication – to the Right Honourable the Lord Burleigh, Lord High Treasurer of England

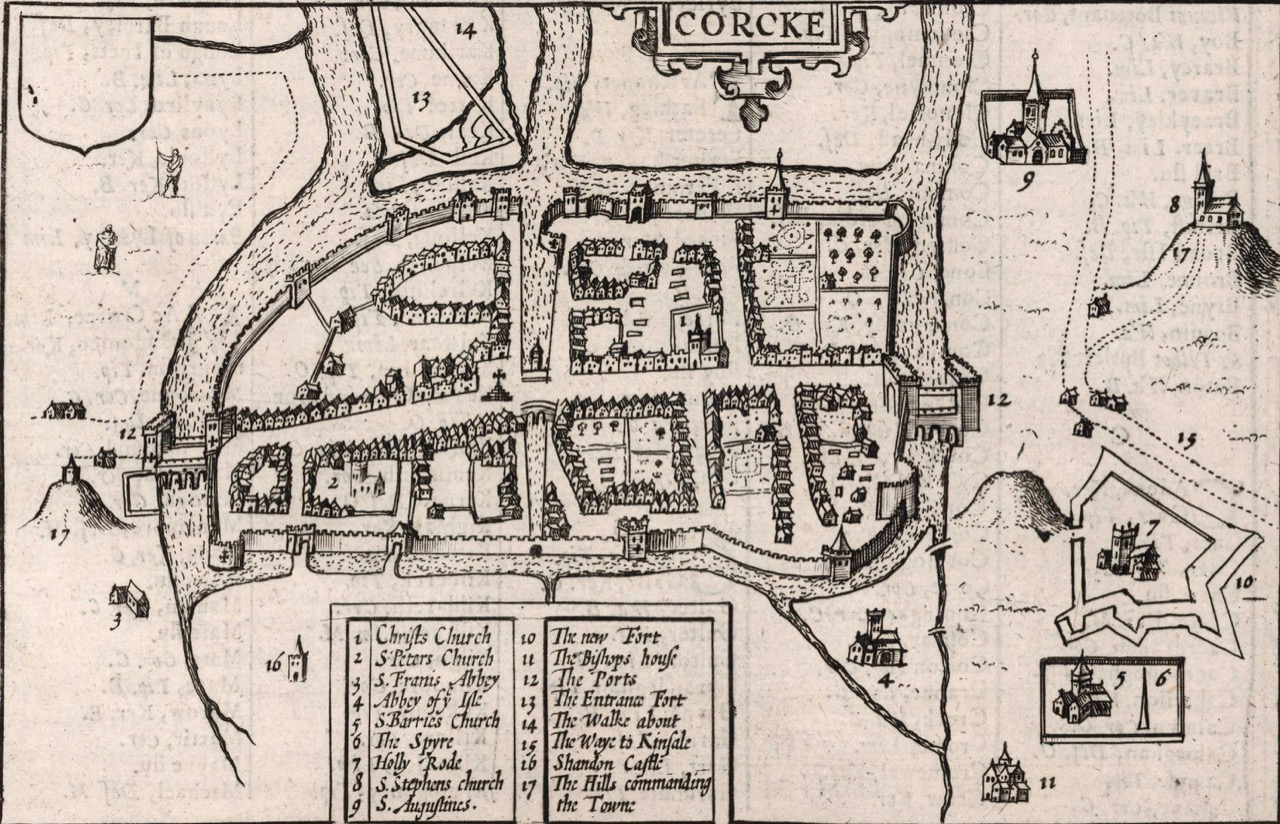

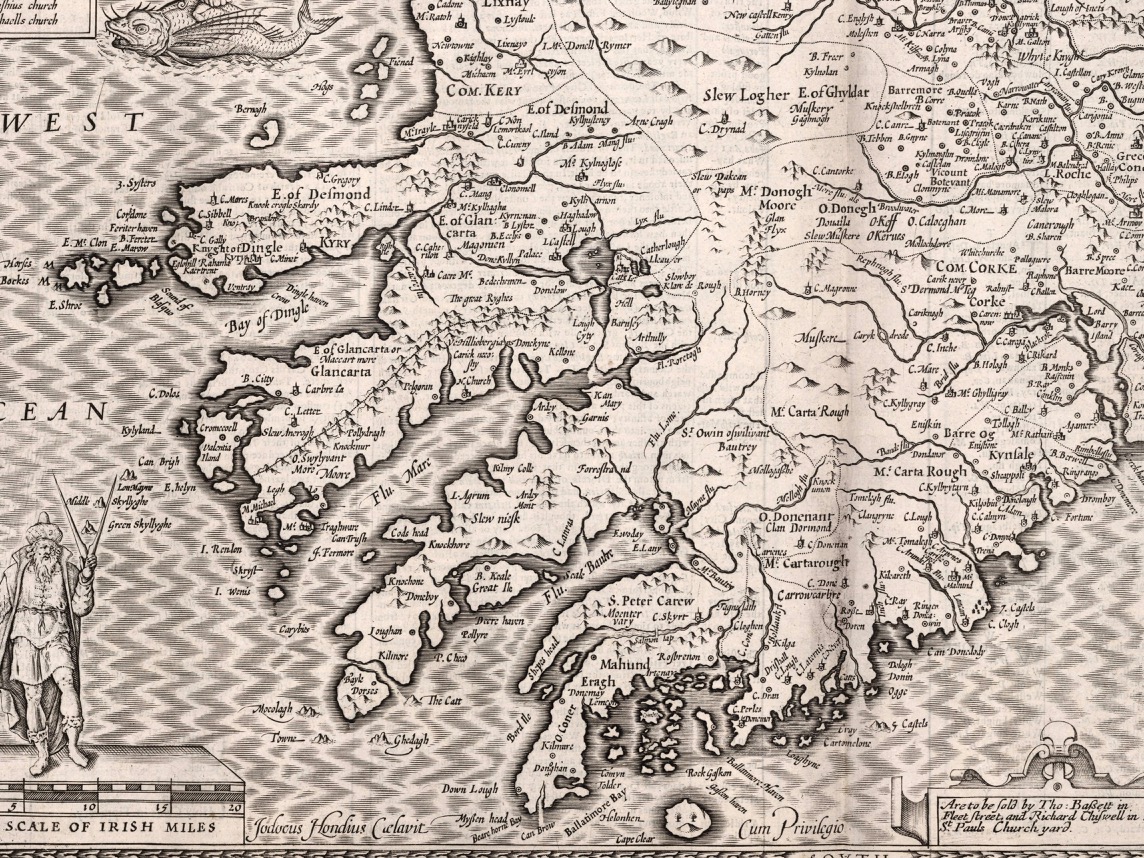

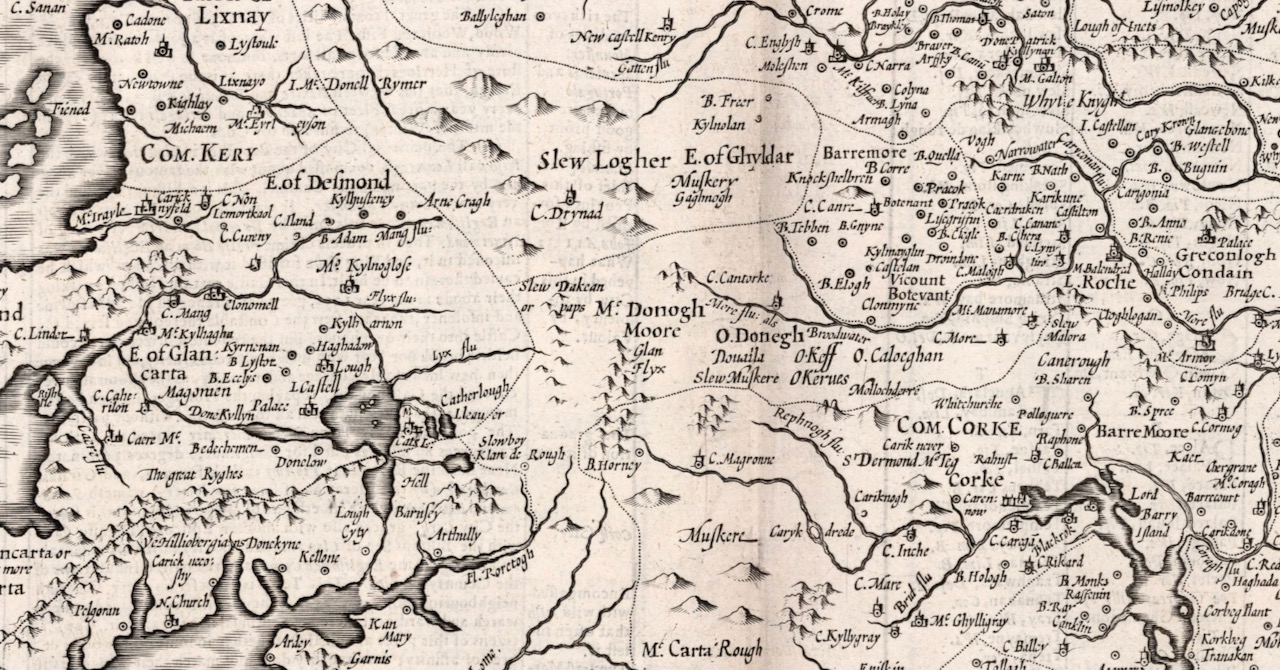

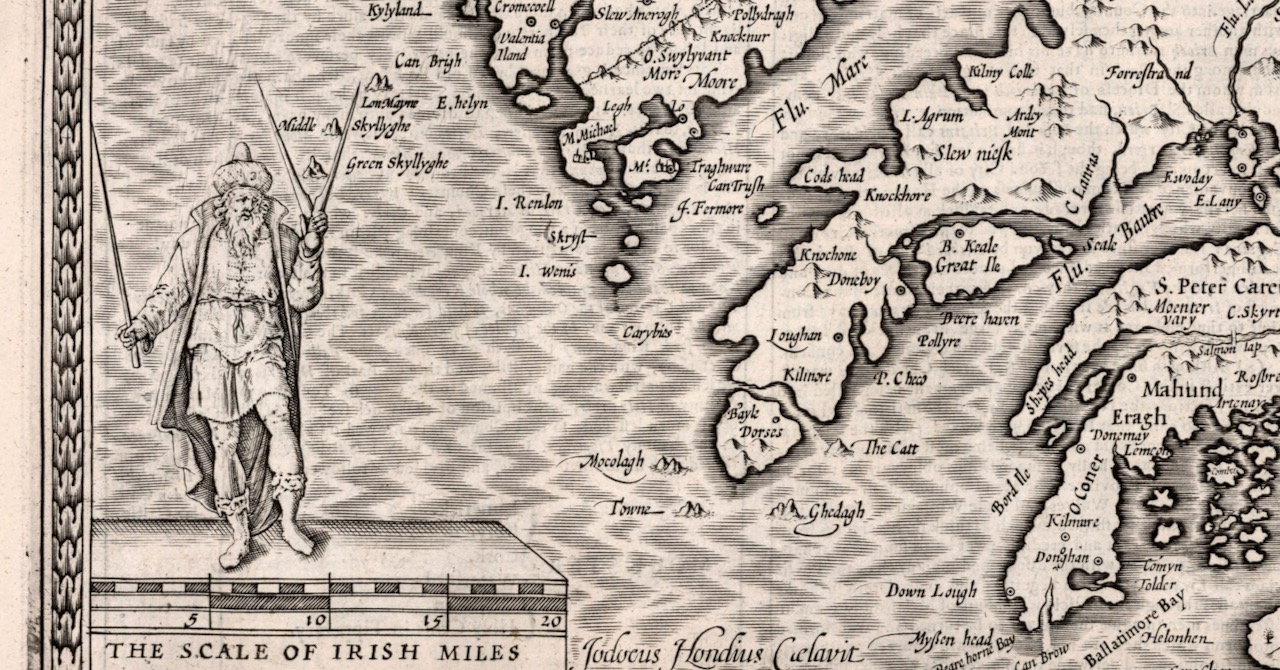

What a project like this needed, of course, was an accurate map and they were hard to come by in medieval Ireland. Francis Jobson, a free-lance cartographer, set himself the task of producing such a map, and in 1589 he inscribed this one, The Province of Munster Map (the subject of this post), to Cecil. The original is in the library of Trinity College and I have been given permission to use it in our blog (see end of post for complete citation.)

Jobson’s signature

George Carew, one of the primary planters, the first President of Munster, was a man who asserted he had an ancestral claim to large chunks of Munster. To back up his various claims, he collected papers and maps in support of the colonising efforts, and these maps later found their way to Trinity College in Dublin, to form part of a collection called the Hardiman Atlas, after the nineteenth century librarian who recognised what they were and bound them together.

George Carew, Earl of Totnes, unknown artist, oil on canvas, based on a work of circa 1615-1620, NPG 409, © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used under License

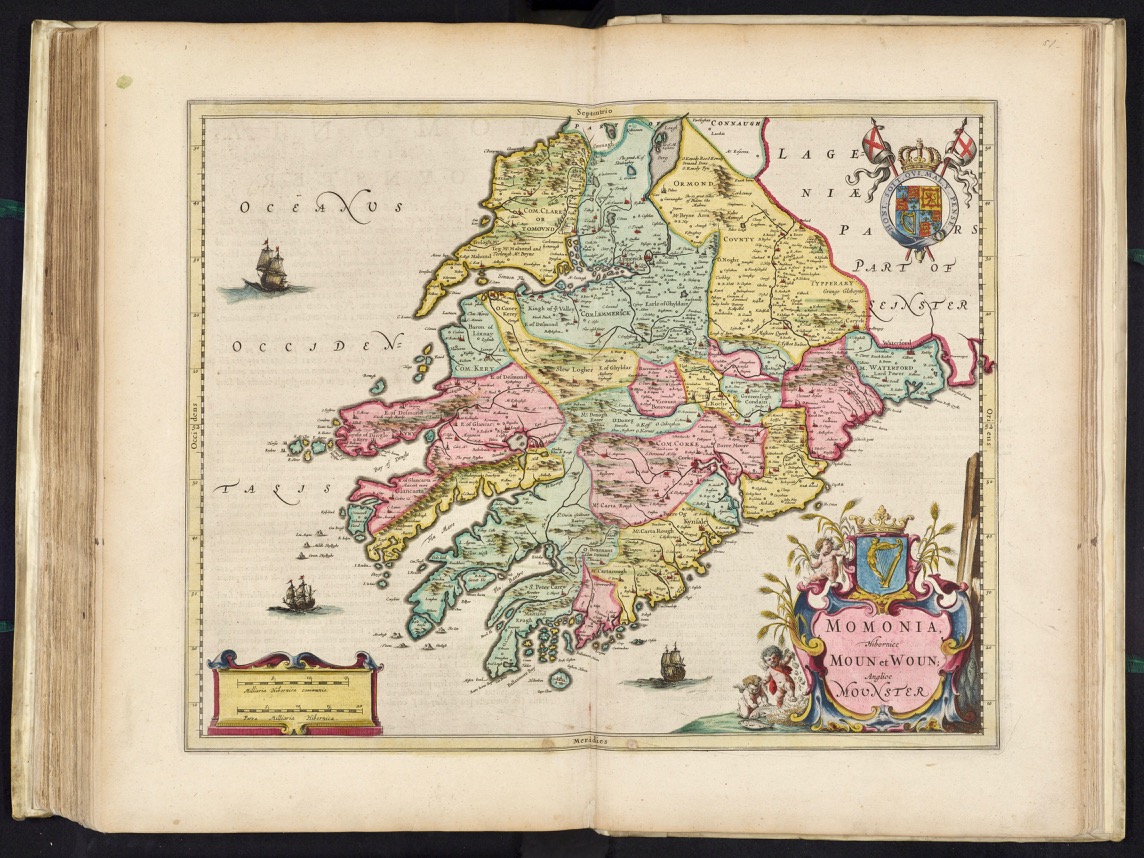

The Province of Munster Map is but one of this collection, now digitised and available for viewing in the Digital Repository of Ireland. And an excellent job they have done of it – the high-resolution image is so clear that it allows us to zoom in and see lots of detail. Here is the complete map.

The first thing that strikes the modern viewer is that Ireland is on its back – that is, instead of north being at the top, west is. This wasn’t unusual for the time. JH Andrews, one of Ireland’s foremost cartographic historians explains it thus, With east at the bottom, Dublin, the Englishman’s point of entry to Ireland, is the point on the map nearest him. To provide a more normal orientation, I have turned the map sideways, below, so you can assess how accurate it is.

The task facing Jobson was to provide as clear information as possible for the colonising effort. Any kinds of fortifications, where the Irish could defend their territory, were important, as were transportation corridors, by sea, river or land, as well as barriers to movement, such as mountains or dense forests. Control of the fisheries had generated great wealth for the Irish chieftains so it was important to have details of coastal areas.

Speaking of Jobson’s Map of Ulster, Annaleigh Margey says

His maps are crucial to our understanding of England’s changing relationship with Ulster at the end of the sixteenth century. As the Nine Years’ War began, Jobson provided representations of the Gaelic lordships in Ulster, but also imposed England’s vision for the creation of a new county system onto the provincial landscape. In Jobson’s 1598 map, now at Trinity College, Dublin (p. 42), this framing of the new political geography is obvious. Throughout Ulster, the various Gaelic lordships are denoted by the lord’s name and a line defining their boundary. Settlements such as castles and churches that could be integrated into English settlement plans are displayed by small replicas in red across the map.

Annaleigh Margey: Visualising the Plantation:mapping the changing face of Ulster

History Ireland, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2009), Volume 17

She could well have been speaking of the Map of Munster. The principal families and their territories are all presented, as well as their main castles. While West Cork is not rendered accurately, we can see what Jobson felt was important to include. The O’Mahonys (Mahound) are there and the castles shown for them are Dunbeacon, Rossbrin and Ardintenant, which is labelled C o mahoun, as befits the castle of the Chief (see my post on Ardintenant here). The whole of Ivaha (now the Mizen Peninsula) is assigned to Mohon (spelling was approximate in these maps) and Crookhaven is indicated, probably because it is an excellent harbour.

The O’Driscolls are shown at Baltymore, with Castles also on Sherkin (Ineseyrkan) and Cape Clere. The Ilen River is shown as the Ellyn ff (ff or flu is often found on old maps to designate a river). Interestingly, the whole of the Sheep’s Head has no detail on it and only one word – Rymers. The O’Dalys were the traditional bards of several Irish families and they had their bardic school near Kilcrohane – they are The Rymers! The Abbey in Bantry is noted (in fact it was a Franciscan Friary) – and even Priest’s Leap is on this map. Once the only land route between Bantry and Kenmare, it is now a steep, treacherous and extremely scenic back road.

We have only just started looking at this map. The next post will continue the journey. Meanwhile – have a look yourself and see what you can see. I have lots of questions about it – for example, about the scale that Jobson uses (above) – I am hoping our readers might have some answers!