The current exhibition at Uillinn, the West Cork Arts Centre gallery in Skibbereen, is a ‘must’ for anyone interested in contemporary artistic expression – but be aware it’s challenging. Having seen the exhibition being assembled before the opening I decided that I would visit it twice – firstly without giving myself any prior knowledge of the subject matter – and then once more, following a gallery tour led by Alison Cronin of Uillinn and a gallery talk by Jennifer Mehigan, one of the participating artists.

I’m very concerned, nowadays, by how ‘art’ is presented, especially ‘art’ which seems divorced from traditional expectations (painted pictures, sculptures etc). I’m fine with all fresh forms of art – and frequently excited by them – but I sometimes wonder whether our artists think about their communication with us… Do they feel that the work should in every way be self-explanatory (we will come away fully informed just by looking at, taking in and understanding the work) – or should their sometimes complex ideas and presentations be explained by accompanying texts, gallery tours, catalogues etc? So I tend to approach every new exhibition with an open mind, hoping for clarity but – firstly – looking for impact from the work. I suppose, at my age, I still think of ‘art’ as being something which should initially stir me, excite me or overwhelm me just through the visual sense: I’m perfectly happy to stand back and look through complex layers of understanding (if necessary) to find the reason for the existence of the artwork, provided it has initially given me that excitement – or whatever emotion – because it will then have drawn me in and made me curious. Some contemporary exhibitions do leave me flat and unstimulated (not many!) and then I have no desire to probe them any further: for me they have failed, but that’s only me, I know. Ultimately, ‘art’ is probably the most subjective of cultural expressions. And that’s all good!

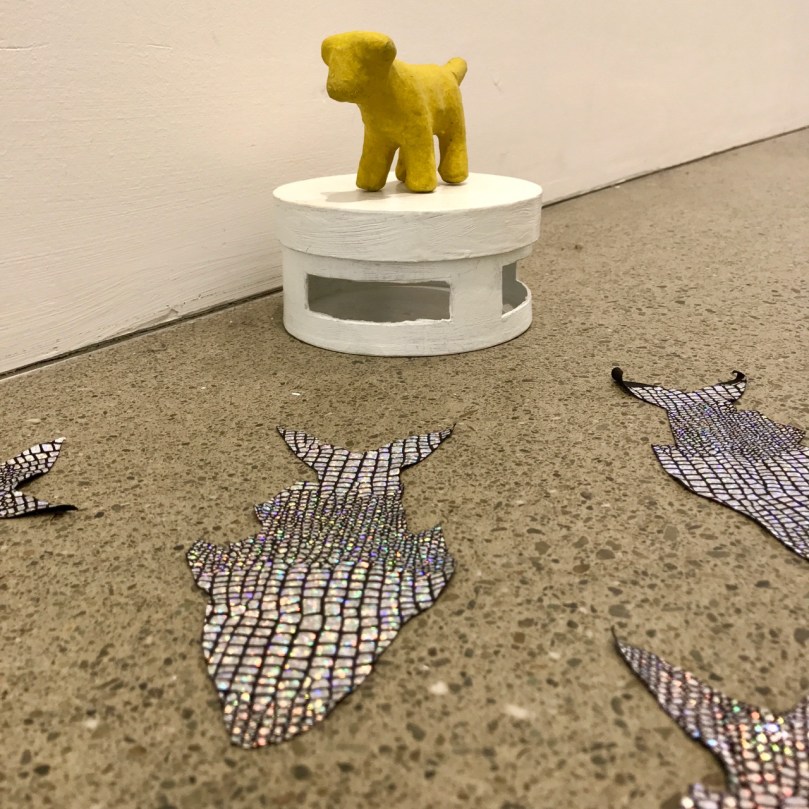

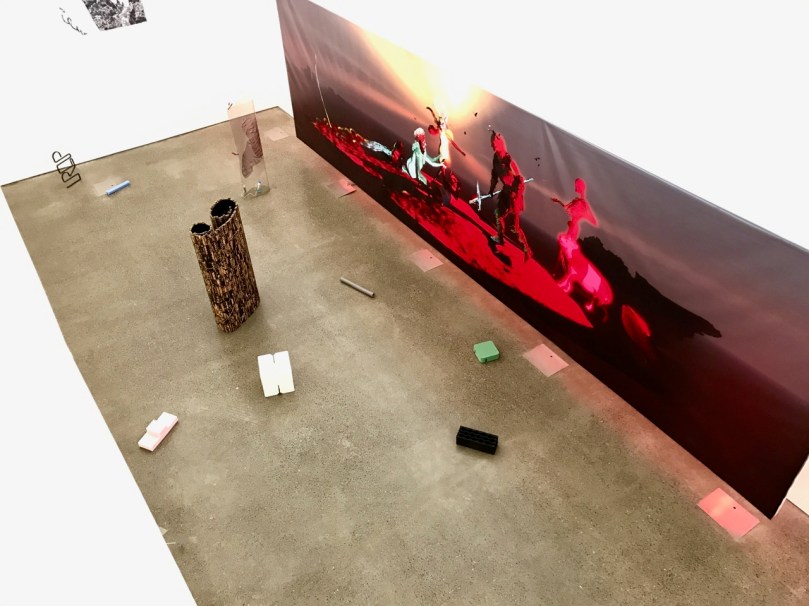

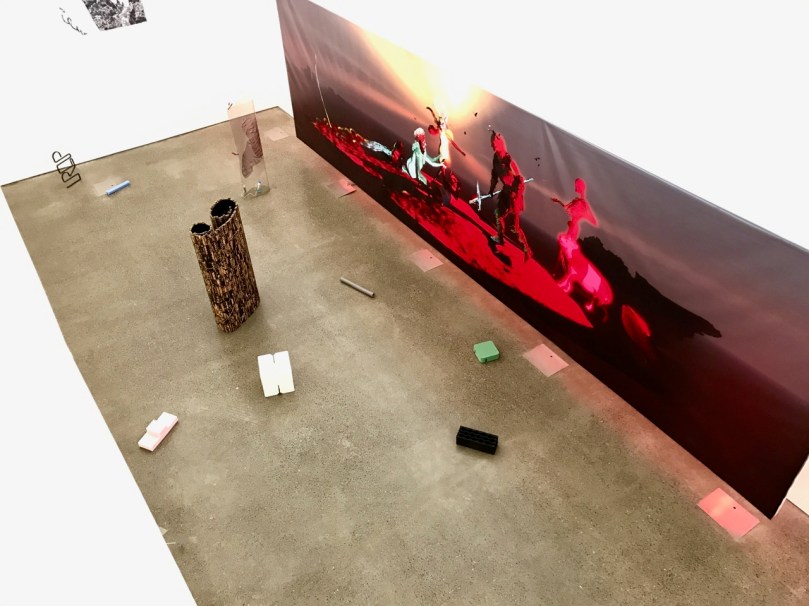

John Russell’s huge backlit print – and two of Eva Fàbregas’s beasts that move around the gallery floor, apparently with a life of their own!

So – how did I react to my initial, completely unguided, tour of Scissors Cut Paper Wrap Stone? I’m pleased to say that I was stimulated – and positively so. I’m always attracted visually by large scale, colour, and things out of the ordinary: that gives you some clues! There are certainly unexpected experiences here. You walk into the first gallery and are hit with a huge print vibrating off the wall, its boundaries emphasised by coloured light behind it. It’s a riot of red – half-human and half- beast figures in a sort of Star Wars tableaux. But then, once you have taken that in you realise that the floor is alive – crawling with more strange beasts that look as though they have had another life as something mundane and practical and are now reincarnated to follow you around the gallery – perhaps to threaten you. What are they? Gallery assistant Kevin enlightened me when he came in to dismantle and repair the mechanics of one of these errant aliens: they are all made from packaging materials fitted with electric motors, and their trajectories across the gallery floor are completely random, referencing, perhaps, their previous lives travelling unsung and unrewarded all around the world. It’s funny how we give life to inanimate (but in this case animate) objects that appeal to us: perhaps it’s a jump back to childhood days when we made things from cereal packets and egg boxes but were then convinced that we had breathed existence into the monsters, dragons, spaceships, princesses (maybe) that we produced. Talking to the gallery staff I was fascinated to hear that some visitors were absolutely convinced that these pieces of mobile packing were imbued with very sophisticated artificial intelligence and really did follow them around and confront them! Remember, this was still before I had any knowledge of the intentions or stimuli behind the exhibits.

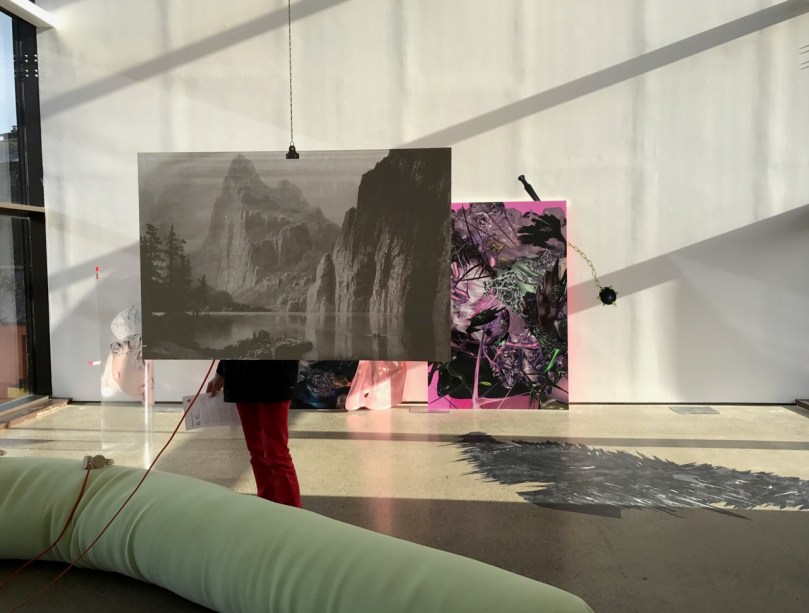

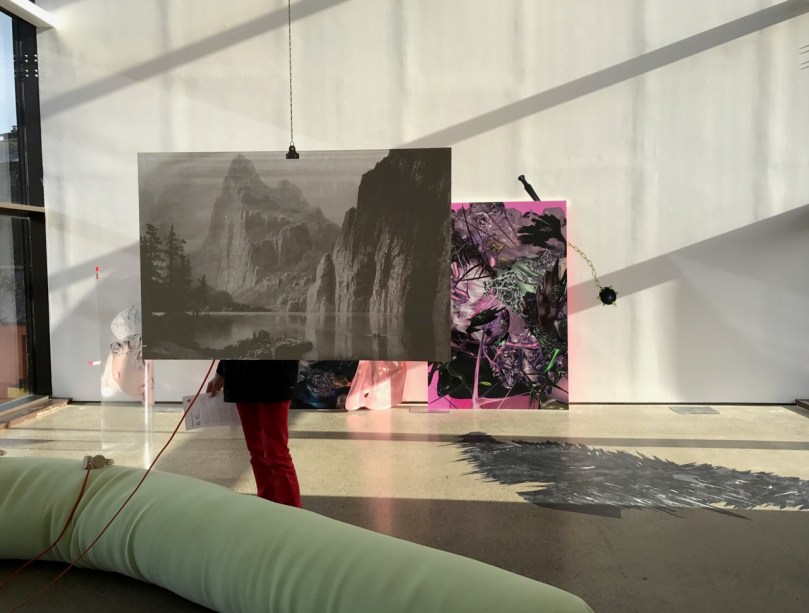

Moving upstairs to the second gallery I found the walkway obstructed by rotating panels of some material (was it glass?) that seemed to be engraved with semi transparent images: they looked like iconic landscape scenes. As I watched, I realised that at certain points in their spinning I was able to see through them, but at the same time also see reflections on their surfaces – of me, of the gallery, of the view through the windows… I liked these very much, and the dymanic nature of their movement and the unpredictable refractions and reflections. I was keen to know how their conception fitted into what I had seen previously downstairs, but I couldn’t guess.

The spinning panels – ‘Orphan Transposition’ – are by Alan Butler and feature acrylic panels laser-etched with images of Yosemite National Park: they also have an intentionally accidental life of their own through the changing surface reflections

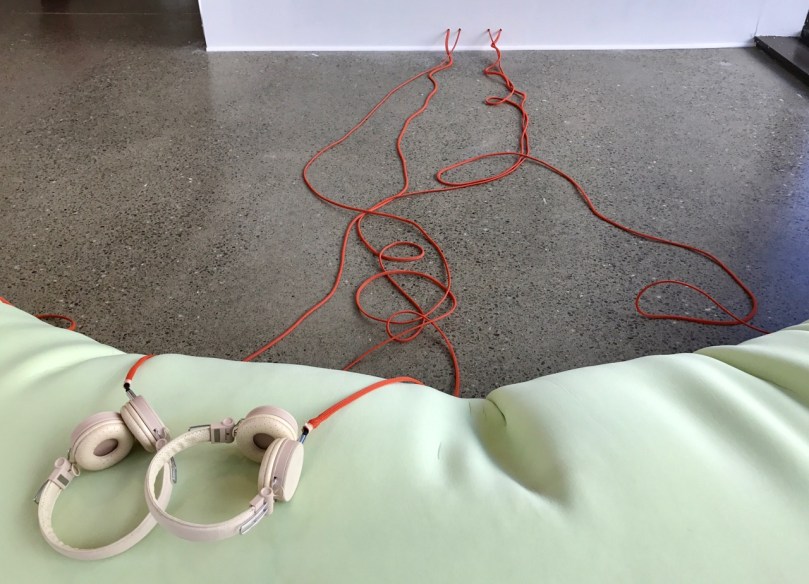

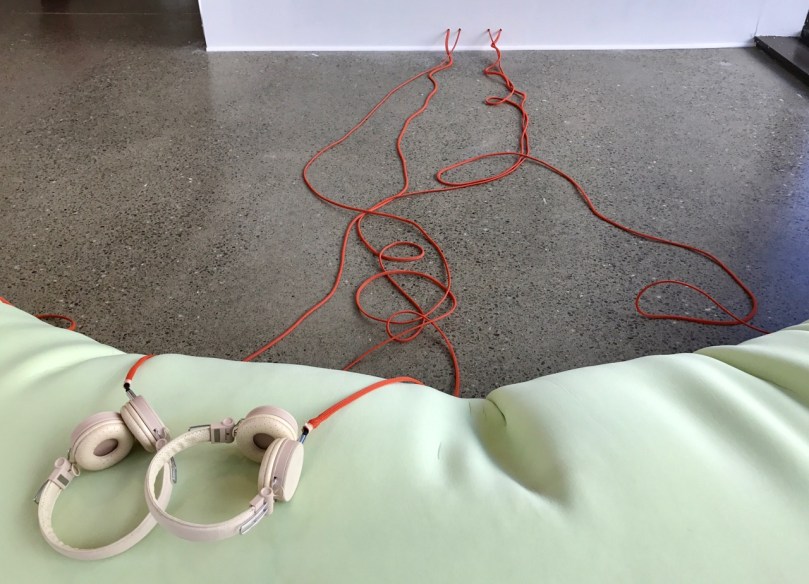

The second gallery held more surprises – and delights. Approaching through a narrow corridor I could see layers: more big, colourful panels on the far wall, more hanging, spinning sheets of opaque transparency, and a very contrasting soft, organic shape seeming to slither across the floor. As I came closer I realised that this shape was not slithering – or moving at all, disappointingly: it was a way of seating people in front of a screen, and was linked in to an array of very funky ‘designer’ headphones (white) by a jumble of thick, red chords.

I sat and watched the ‘show’ – and listened to clunky music and a strange commentary – and then realised I was completely out of my depth! I had no clue what was going on. My attempt to experience the exhibition without any preparation or foreknowledge had failed. This applied to all the other work in the upper gallery also: superb large graphics on the walls and floors, printed acrylic sheets suspended on smart steel stands, and, in a darkened cubicle, a film of puppets which reminded me completely of ‘Bill and Ben the Flowerpot Men’! Now, how many of you remember them, dear readers? I don’t suppose any of the contributing artists are of my generation – so, is that pure coincidence? Anyway, I could not feel a sense of connection between the exhibits: but I liked the experiencing of them, nevertheless.

Upper – Eva Fàbregas’s The Role of Unintended Consequences (Sofa Compact) – which can be enjoyed on the comfort of a squishy serpentine furniture sculpture – and, lower – puppets feature in Andrew Norman Wilson’s Reality Models

It all began to come together and make sense when I took the gallery tour and artist talk (having first read an accompanying written commentary). Wonderful! The title of the exhibition – Scissors Cut Paper Wrap Stone – which I only knew as a childhood game (and one which I played with my own children) is also the title of a science fiction novella written by Ian McDonald (from Belfast) in 1994. It’s evidently something of an iconic work for those who follow the genre (I don’t particularly, although I have read a little sci-fi). I now know that the participating artists were asked to familiarise themselves with the book and respond to it in a way which they feel comments on our present times: there was no collaboration as such between the artists on the overall exhibition (as I understand), but the curators have put the work together in a way that does begin to set out a narrative.

In the optional (€12) catalogue that accompanies the show, Alissa Kleist & Matt Packer (the curators) write an introduction. I was struck by this paragraph:

…From an artistic perspective, Scissors Cut Paper Wrap Stone [ie the book] can be read as a wishful fantasy of artistic power. It describes visual art without recourse to the systems of academic analysis and understanding that have defined the art-history books for the past century and more; instead it promises an encounter with art that frees the ‘rapture’ that Jean-Francois Lyotard describes as being harboured within art itself: an art that hits us straight to the core of our physical being…

Wow! isn’t that what I was trying to say about my approach to new exhibitions – looking for impact from the work, being stirred, excited or overwhelmed before having any understanding of it? It’s a wonderful way of putting it: …the ‘rapture’ harboured within art itself… Suddenly, I realise that I’ve approached this exhibition exactly as the curators would want me to: first I have the visceral experience, then comes the understanding! Or is it that I have now walked into the exhibition and become a part of it?

Back to the book (via the catalogue):

…In the book, McDonald tells the story of a young student, Ethan Ring, who develops the ability to create digital images that bypass rational thought and control the mind of the viewer…

I’m worrying now – am I being controlled by the digital images in the exhibition?

…Ethan develops a technology of ‘fracters’ – mind-controlling images that have the power to heal, cause pain, induce tears or ecstasy. The utopian promise of this image technology is short-lived as Ethan finds himself blackmailed into employment by the ‘Public Relations’ department of the ‘European Common Security Secretariat’, who demand that he uses the fracters for the purposes of interrogation and assassination, as and when they require…

This is frightening stuff. The book was written in 1994 but in our own time we are suddenly being confronted by concepts of ‘fake reality’ – and aren’t we shocked by governments who seem to be veering off into nonsensical directions, apparently against the wishes of the public majority? Suddenly, I’m seeing an uncanny relevance which these artists – inspired by the concept of the book – have made to our own predicaments. From the catalogue again:

…In a way that is typical of the cyberpunk genre of science fiction, Scissors Cut Paper Wrap Stone is written with the strategy of combining prosaic everyday miseries with the ‘cognitive estrangement’ of a world that has been accelerated beyond our control…

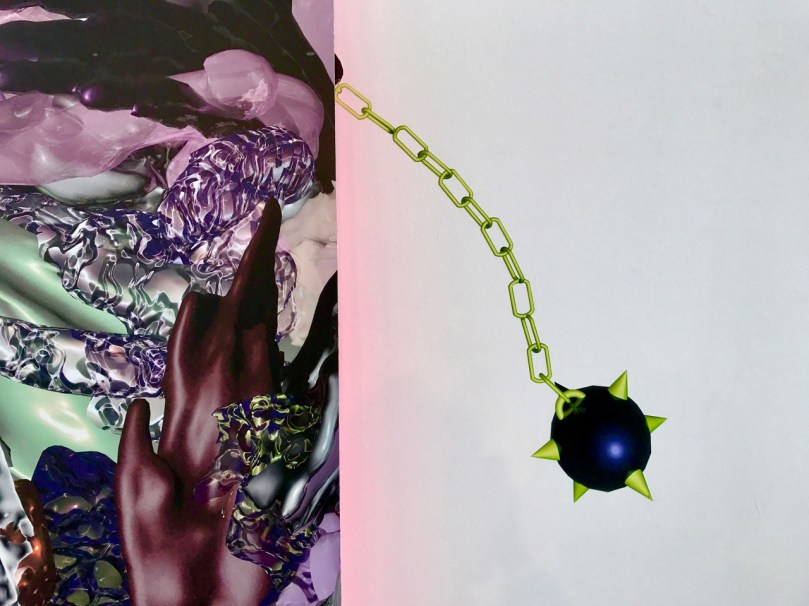

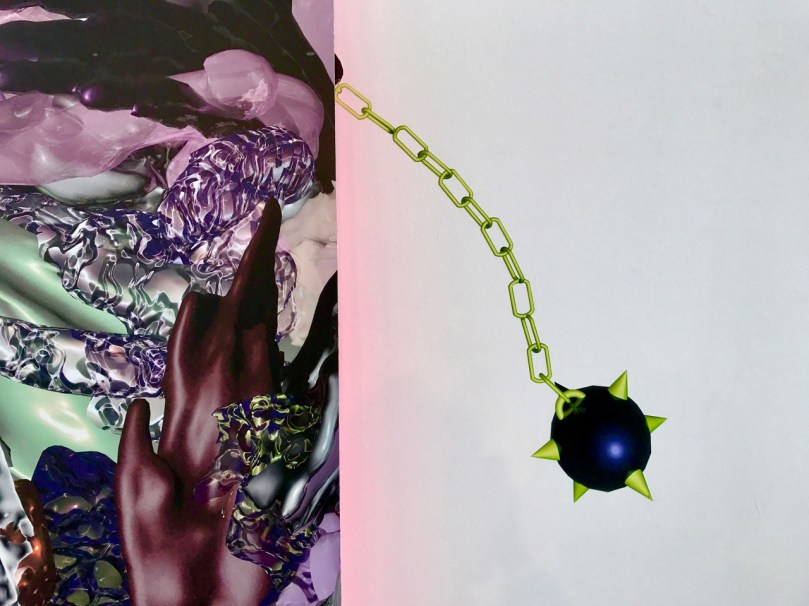

A detail from one of Jennifer Mehigan’s stunning prints made from collages of three-dimensional digitally generated models: this one illustrates the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy virus – better known as Mad Cow Disease

Lastly, I should mention the gallery talk by Jennifer Mehigan. She has only been involved in the Uillinn, Skibbereen, iteration of this show. Knowing that now, I think the overall exhibition will have been considerably poorer without her contribution. I think my strongest instant reactions (rapture?) have been to her large digitally produced panels. Now that she has explained their conception I am even more impressed. She asked us to consider the cow…

The cow is an unnatural beast. Human intervention keeps it permanently fertile so that it produces food for us. It gives us its milk: it dies for us. But also – again through human intervention – it eats itself. This generates the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy virus – better known as Mad Cow Disease. This kills humans. Be afraid…

Jennifer’s gorgeous panels are made using a highly complex technology – 3 dimensional modelling software. With this software she has constructed a cow’s stomach, bacteria found inside the human gut, the mad cow disease virus, and Drombeg Stone Circle (that’s the link to human intelligence). She’s put all these things together into bizarre, visually stunning collages and presented them to us as compelling two-dimensional images leaning up against the end wall in Uillinn where they sparkle and shine in the sunlight: we are seeing the fracters and, behind them, the government departments who are manipulating world perceptions of reality.

Powerful images from a strong exhibition. Step beyond the images and we see power – or a commentary on power. Statements are being made here – perhaps subversively – about the world in which we live today. That’s great – that’s art.

The exhibiting artists are: Alan Butler, Pakui Hardware, Jennifer Mehigan, Andrew Norman Wilson, Clawson & Ward, Eva Fàbregas, John Russell

Scissors Cut Paper Wrap Stone is on at Uillinn, Skibbereen until 25 February 2017. The gallery is open Mondays to Saturdays from 10.00am to 4.45pm: there are guided gallery tours on selected Saturday mornings – check with Uillinn: enlightening and well worth attending! Here’s Alison Cronin in action:

Email link is under 'more' button.