Our travels are always attuned towards our particular interests, be they history, stained glass, art or – as in this case – archaeology. We go out of our way to take in sites we have never seen before – and there are so many. When we were ‘holidaying’ in Wicklow last week we searched out this stone circle in the townland of Castleruddery Lower. It was well worth the journey.

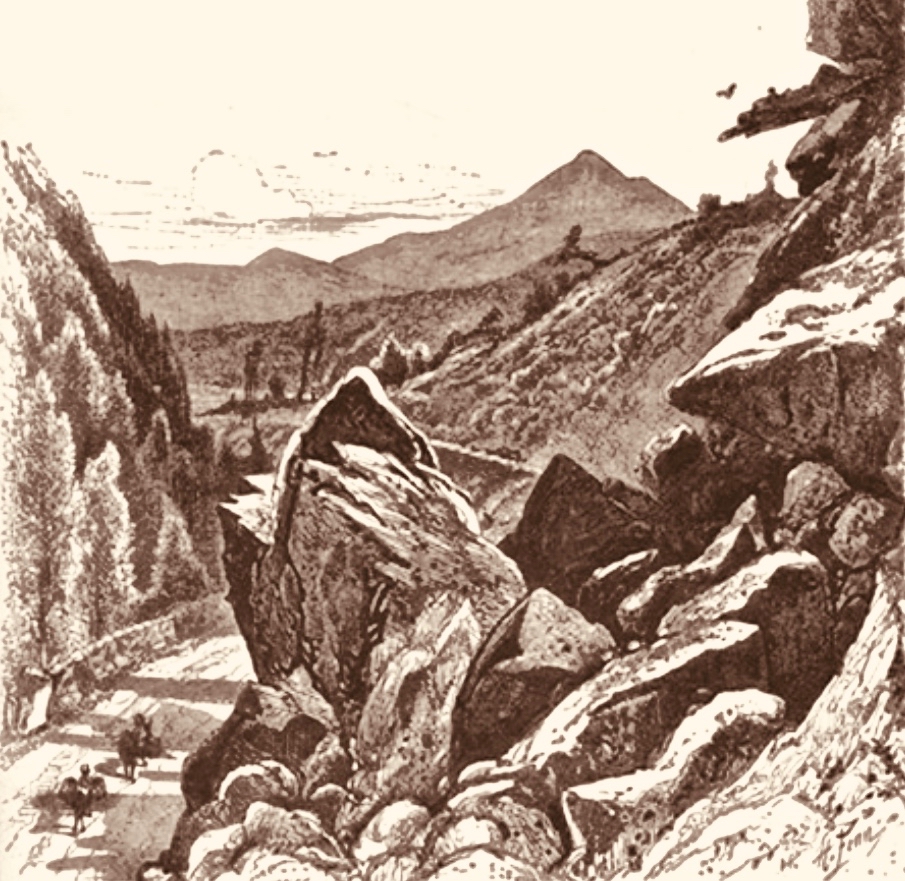

. . . Neglected, knee-high in grass and surrounded by round-crowned hawthorns whose May blossom speckles the bank, it is difficult to appreciate how important Castleruddery must have been early in the Bronze Age when Beaker copper prospectors and the Wicklow mountain goldminers passed by its brilliant entrance. It is not properly a stone circle but a henge, with a stone-lined interior. It was constructed on the summit of a hill just east of the valley into which the Little Slaney flows. Six miles north is the lovely Athgreany stone circle and only two miles to the south is the Boleycarrigeen ring, its stones embedded in a low earthen bank . . .

Aubrey Burl, Rings of Stone, France Lincoln Publishers, 1979

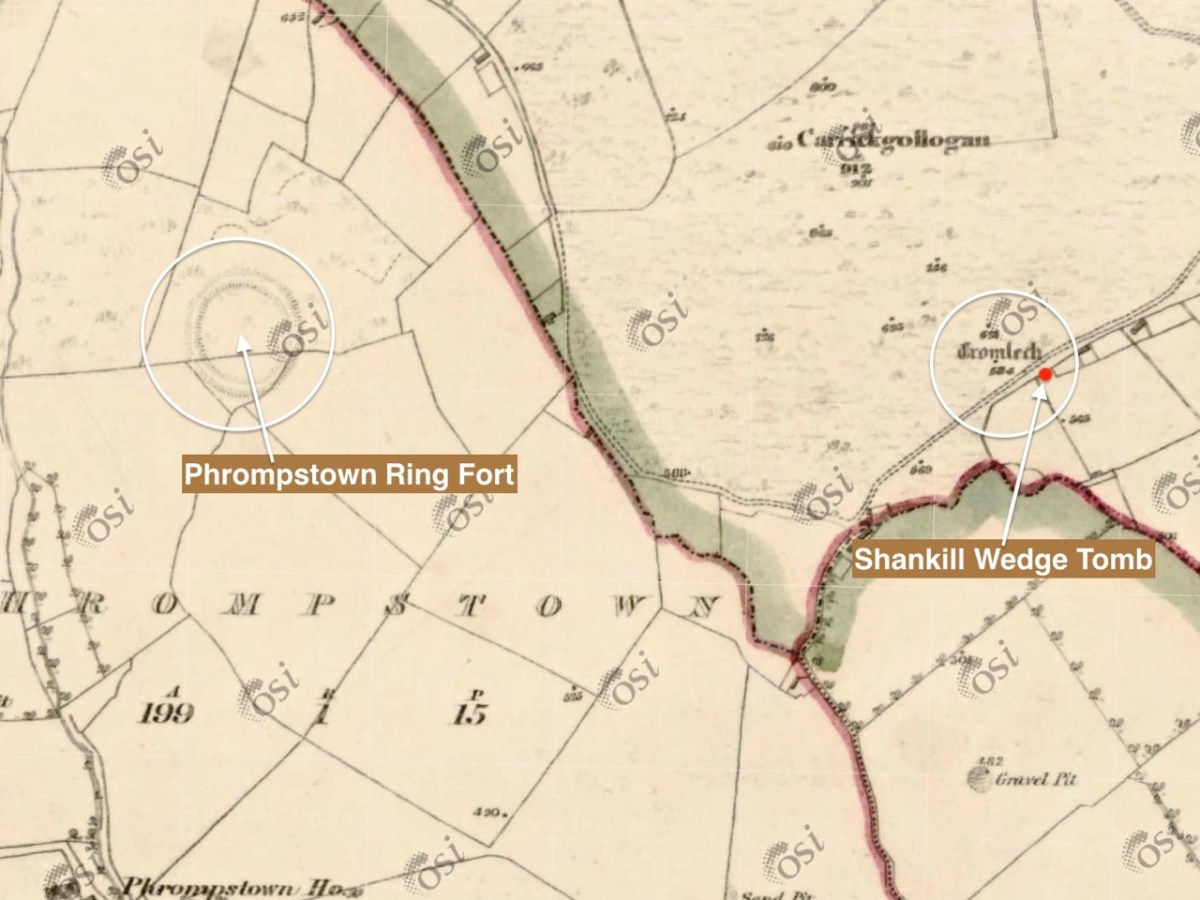

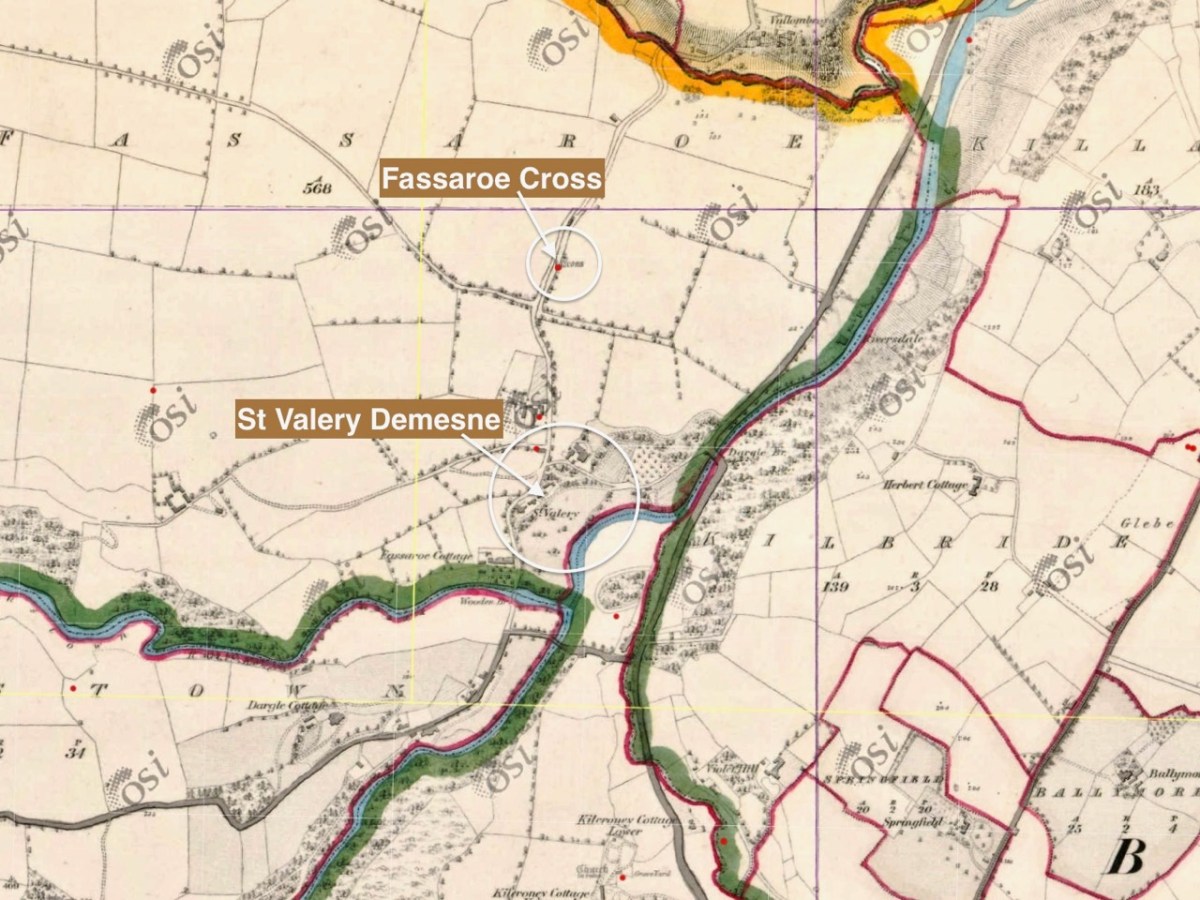

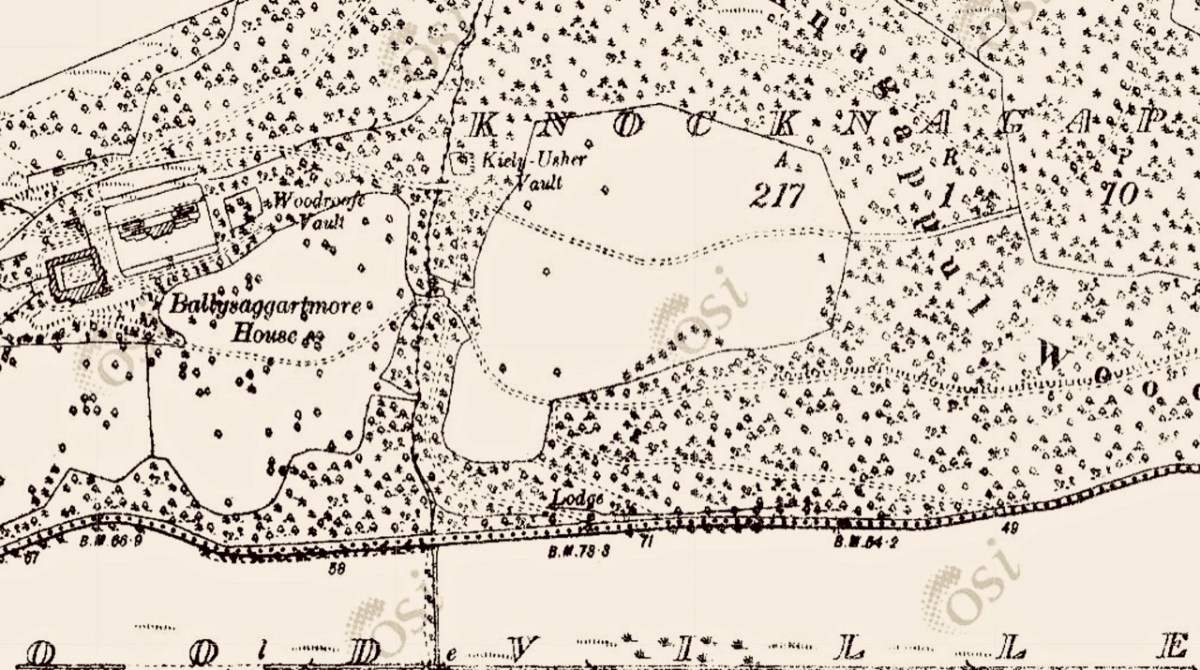

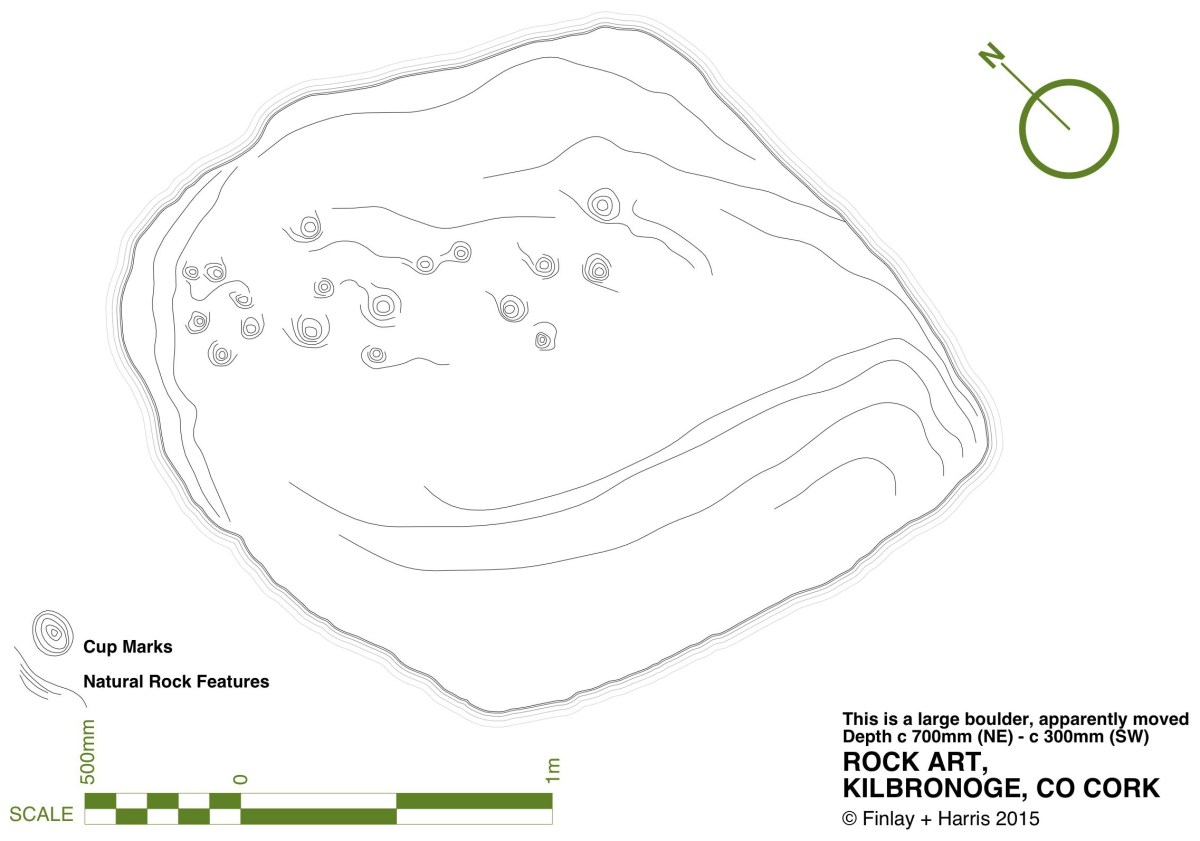

The aerial view, and the extract from the 25″ Ordnance Survey map (above) show the monument in the context of the surrounding landscape. Nearby is a medieval ‘Motte’, very much younger than the ‘Druidical Circle’ – thus named on many early maps. The local Irish name – Chaisleán an Ridire – translates as Knight’s Castle, which might make you think that there is some medieval connection between the circle and the Motte, but in fact Castleruddery stone circle is likely to date from the late Neolithic, around 2,500 BC, marking it as one of the earliest of this monument type in Ireland.

We noted this little figurine by the entrance gate to the circle: it made me wonder what folklore or traditions might be associated with the site today. I could find only one reference to Castleruddery in the Duchas Schools Folklore collection, dating from 1936:

The informer here was Michael Murphy, aged 68 – a ‘labourer’ from Colliga, Co Wicklow. The School collector was from Baile Dháithí, Dunlavin, Davidstown, Co Wicklow. There was no doubt in Mr Murphy’s mind that the stones could only have been placed there by supernatural powers!

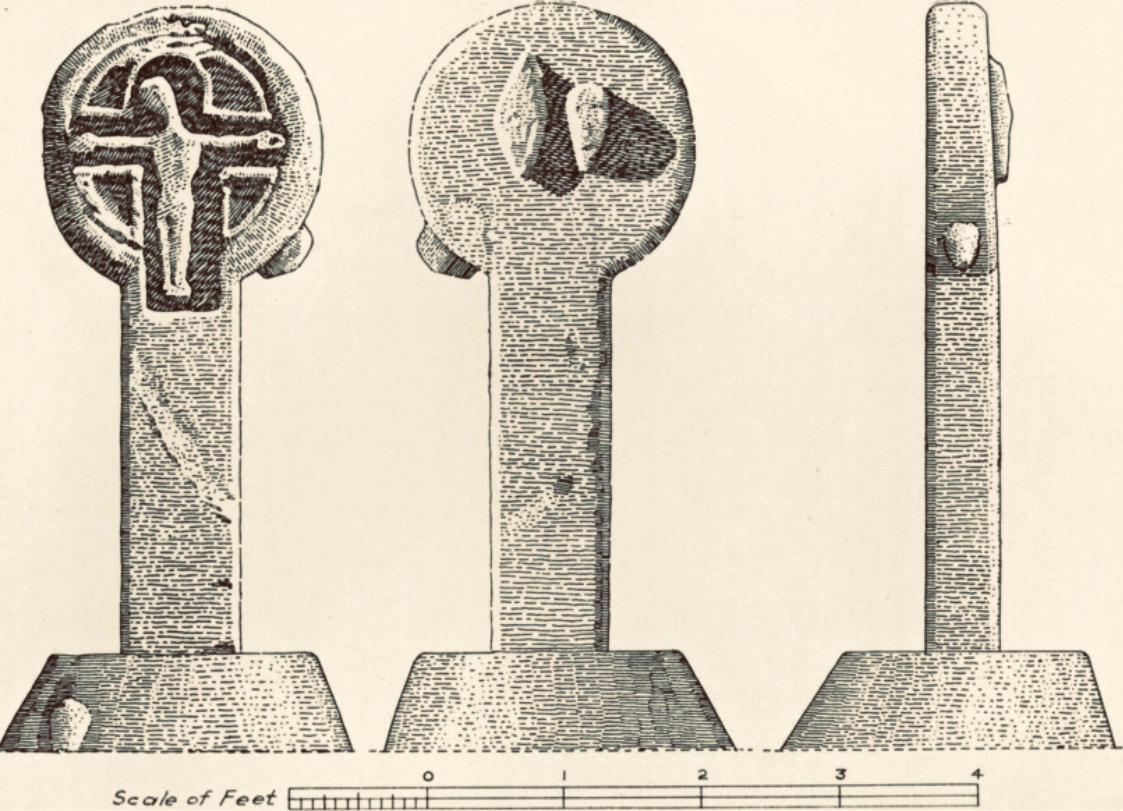

The two quartz portal stones at the east side of the circle are remarkable: deliberately chosen, no doubt, to emphasise the importance of the orientation. The circle has 29 significant stones still standing today, but there were probably more. There is evidence of attempts to break up and remove some of the stones, which would have made good building or fencing material for someone who did not share respect for the integrity of the circle.

The two views above show iron ‘drill’ markings: these were made to try and separate sections of stone to be taken away for re-use. In the upper picture one section has been removed, but the operation was unsuccessful for the remainder of the boulder. One has to wonder whether otherworldy forces intervened – and meted out some form of ‘bad luck’ to the perpetrators.

In the present day it’s territory for sheep, and they seem to be unconcerned about any ancient associations or supernatural influences interrupting their tranquil grazing. The archaeologists tell us that this is more of a ‘henge’ monument than the type of stone circle we are familiar with in West Cork. It’s certainly larger, and crop marks have shown that the 29 stones surmount an earthen ring, approximately 30 metres in diameter, and there is a further ring which was once supported or reinforced by timber. Comparisons are made with a henge circle at Grange, close to Lough Gur, Co Limerick, which we visited in 2016. There the ring of at least 113 stones has an internal diameter of 46 metres. We took the two photos below at Grange.

The Grange circle was excavated in 1939 by professor S P Ó Riordáin, and the Duchas board at the site states:

. . . The excavation indicated that the enclosure was constructed purely for sacred or ritual purposes. The bank may have provided a stand where an audience could observe ceremonies within the enclosure . . . One of the stones is known as Rannach Cruim Duibh. This suggests that the circle became associated with the festival of Lughnasa, traditionally the first Sunday in August, and a celebration of the harvest. Crom Dubh, meaning the Dark Bent One, was credited with bringing the first sheaf of corn to Ireland . . .

Duchas, Grange Circle

There must surely be connections, and common purposes, between the many similar circle monuments all over Ireland. We always want to know What was it for…? probably, we never will, but it’s part of the whole romance of archaeology to wonder about such places. We must be grateful that so much remains for us to explore.