When St Brendan of Clonfert set out to discover America in 512 he and his fellow monks had to face the enormity of the Atlantic Ocean in tiny boats built out of wood and oxhides, sealed with animal fat. Up here in Nead an Iolair our view out to the islands of Roaringwater Bay and beyond is dominated by that same ocean and – sometimes – we feel just as small. This year the winter gales have started early, and spates of fierce westerlies have been throwing the Atlantic straight at our windows. The tiles rattle alarmingly while we are tucked up in bed at night. At these times I think of the Saint and what he had to face. But, like Brendan, we always survive the storms, and often wake up in the morning to a calm, clear day – except that you can hear the constant ‘roaring’ of the open sea out over the bay.

On their way to the New World – Saint Brendan and his companions take advantage of a passing Atlantic denizen to celebrate Mass…

On their way to the New World – Saint Brendan and his companions take advantage of a passing Atlantic denizen to celebrate Mass…

The Atlantic has shaped Ireland. The sea is omnipresent: poets have written about it, storytellers have woven tales around it, and composers have tried to capture its spirit in music. Here’s a small section from the impressive ‘Brendan Voyage’ written by Shaun Davey for orchestra and Uillinn pipes – it’s the haunting second movement, played by Liam O’Flynn with the Irish National Youth Orchestra, at a performance in Cork City Hall. It makes me think of the wonderful sunrise on that calm day after the storm…

Brendan Voyage

Our own Atlantic: telescopic view of a storm battering Long Island, taken from our garden at Nead an Iolair (top), Brow Head, near Crookhaven (centre), and the impressive land and seascape at Mizen Head – Ireland’s most south-westerly point (lower picture). At the head of this page you can see the huge rollers that come into Dingle Bay, Co Kerry

Dogger, Rockall, Malin, Irish Sea:

Green, swift upsurges, North Atlantic flux

Conjured by that strong gale-warning voice,

Collapse into a sibilant penumbra.

Midnight and closedown. Sirens of the tundra,

Of eel-road, seal-road, keel-road, whale-road, raise

Their wind-compounded keen behind the baize

And drive the trawlers to the lee of Wicklow.

L’Etoile, Le Guillemot, La Belle Hélène

Nursed their bright names this morning in the bay

That toiled like mortar. It was marvellous

And actual, I said out loud, “A haven,”

The word deepening, clearing, like the sky

Elsewhere on Minches, Cromarty, The Faroes.

Glanmore Sonnets VII, taken from Field Work by Seamus Heaney, published by Faber and Faber Ltd

Seamus Heaney was deeply affected by the seascape of his native Ireland. Anyone who works on or beside the sea is aware of the resonant names from the Shipping Forecasts, and the poet has used those names here to introduce his word-picture of the elemental Atlantic.

Atlantic contrasts from Mizen to Malin: near Malin Head – Ireland’s most northerly point (top), off the Beara (centre) and a beach in Donegal (lower)

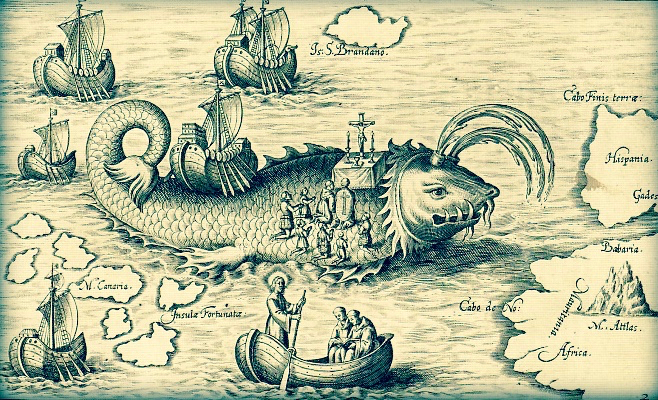

A later traveller over the Atlantic waters was Chistopher Columbus in the 15th century. On the way he looked out for St Brendan’s Isle, a spectral island situated in the North Atlantic somewhere off the coast of Africa. It appeared on numerous maps in Columbus’ time, often referred to as La isla de Samborombón. The first mention of the island was in the ninth-century Latin text Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abatis (Voyage of Saint Brendan the Abbot), from whence it became firmly implanted into Irish mythology. St Brendan took a little party of monks to the island to say Mass: when they returned after a few days to the rest of the flotilla, they were told that they had been away for a year! The phantom island was seen on and off by mariners for years until in 1723 a priest performed the rite of exorcism towards it during one of its apparitions behind low cloud… You can see St Brendan’s Isle for yourselves, above the wonderful giant fish in the second picture down.

Dingle peninsula (top), and Coast Road in Donegal (lower)

I was pleased to find this Irish Times video made by Peter Cox when he was fundraising for his book Atlantic Light: spectacular photographs of the coastline on Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way. The excellent aerial views in this film are all taken by a drone… Look out for places you will have seen in our blogs!

atlantic video

We are privileged that the Atlantic Ocean is the abiding but ever-changing feature in our daily lives. It must affect us in unknown ways: I do know that, wherever I go in this world, I will – like Saint Brendan – always be drawn back here to our wonderful safe haven…