It’s March – an important month, in Ireland, for saints. This week we will celebrate St Patrick, of course. But there’s another – dare I say equally important – Irish saint whose day we have just passed by. That’s Saint Ciarán, and we are particularly keen to give him an airing, as he was born on Cape Clear, which we look out onto every day! That’s the view (above) from our home across Horse Island and Roaringwater Bay towards ‘The Cape’, which sits on the horizon under a wonderfully atmospheric sky. I also feel drawn towards Ciarán because his ‘day’ – March 5 – happens to be my birthday. And – as you will see – there’s another personal connection: I lived in Cornwall for many years, and that’s where some of my forebears hale from. Would you believe that this same saint is also the Patron Saint of Cornwall? Read on . . . But be aware that I have published this post before, several years ago – when RWJ publication day actually fell right on my birthday. I’m giving myself a day off the hard writing this week, as I have been recuperating from a little ‘op’ in Cork. Here goes:

I was born in the first half of the last century. Early memories of the 1950s include the regular journeys my brother and I made as small boys on the mighty Atlantic Coast Express via Okehampton to visit, first, our sets of cousins on Dartmoor, and then beyond – via the even mightier Great Western Railway – to our cousins in the depths of Cornwall. The latter visits were particularly idyllic: the cousins (generations older than us) had a small farm and a herd of cows which they milked twice a day – by hand. Following this they cooled the milk in a big steel drum by stirring it with a propellor (we were allowed to do this) before pouring the precious liquid into bottles which were then sealed with silver caps using a rubber device which impressed on them the name ‘Cove Farm’. Then, together, we set out on bicycles to deliver the bottles to the doorsteps of every dwelling in the small village of Perran-ar-worthal.

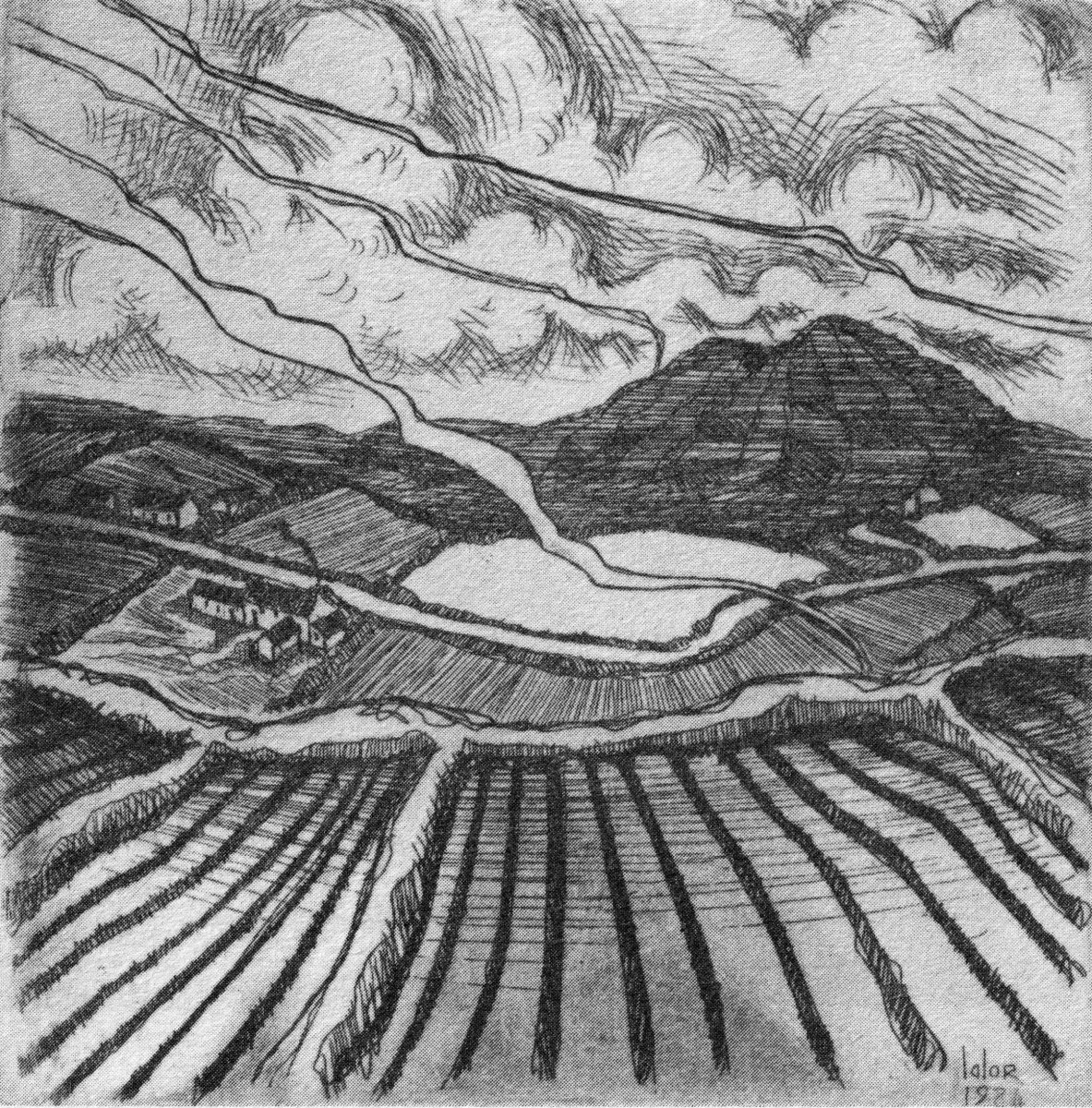

Perranwell Station 1950s – disembark here for Perran-ar-Worthal and Cove Farm!

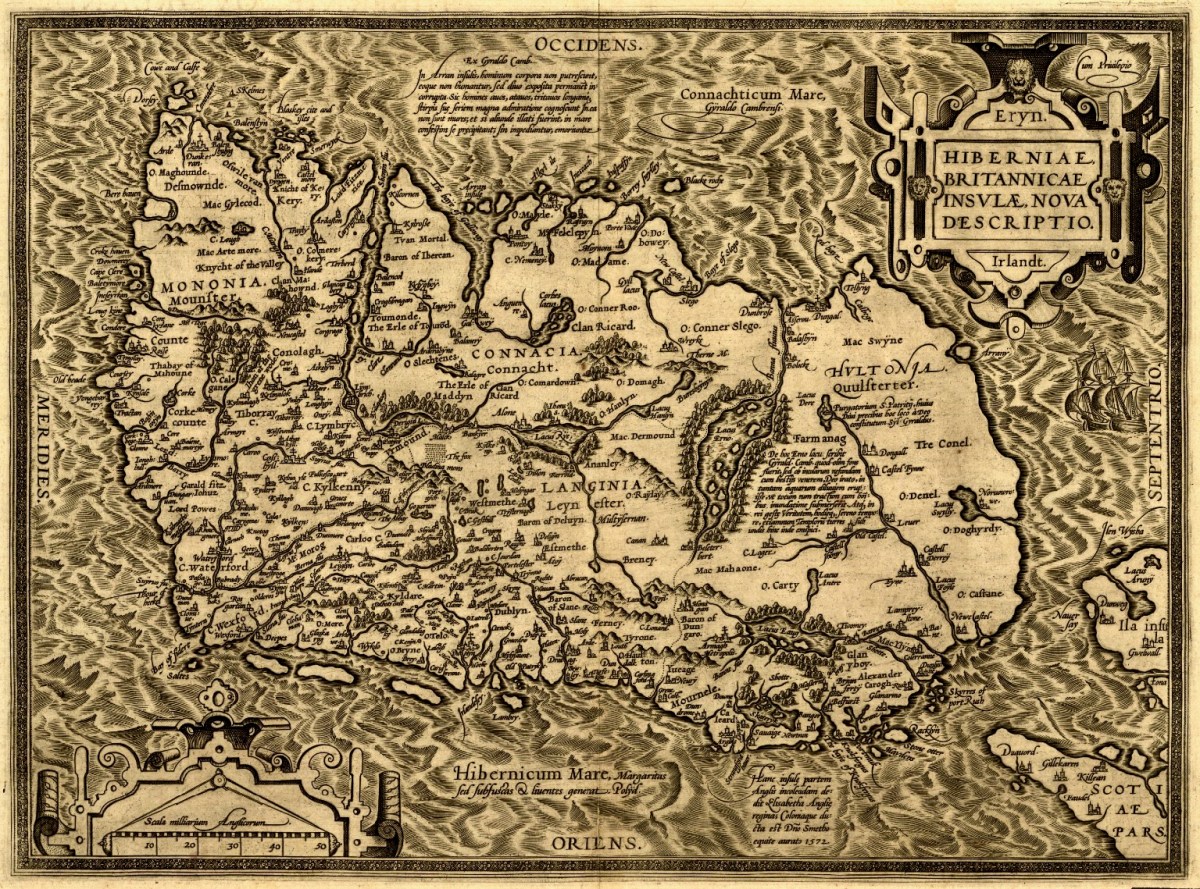

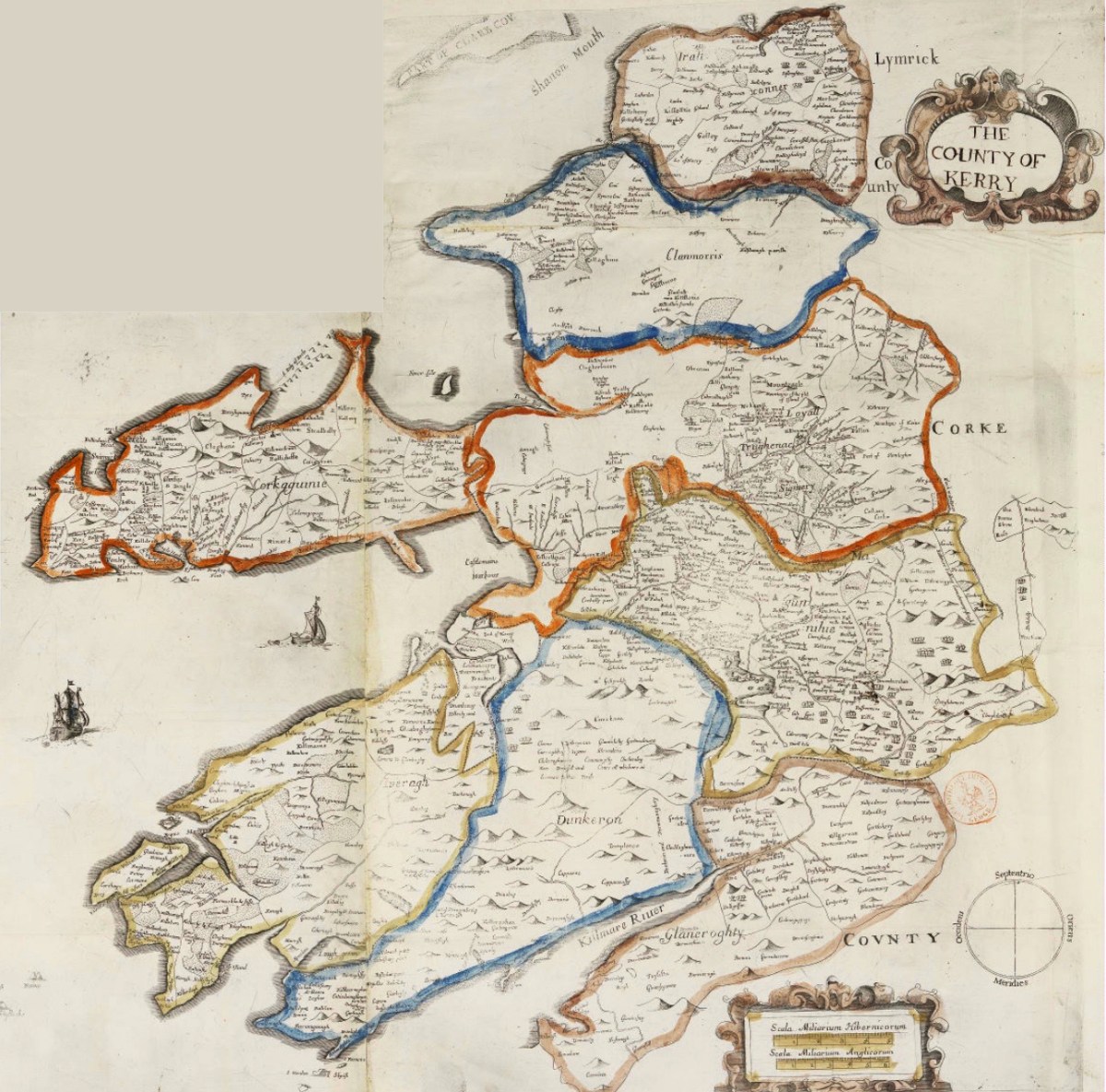

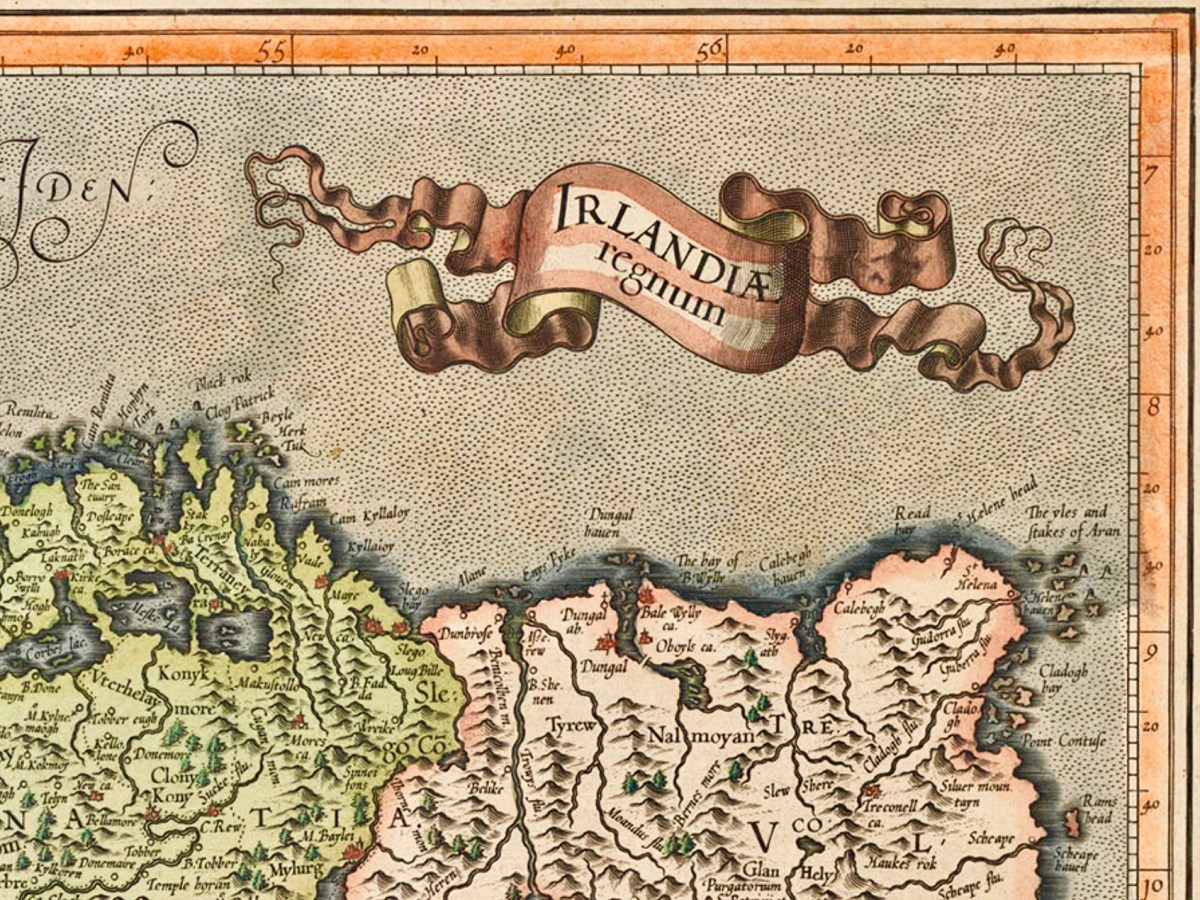

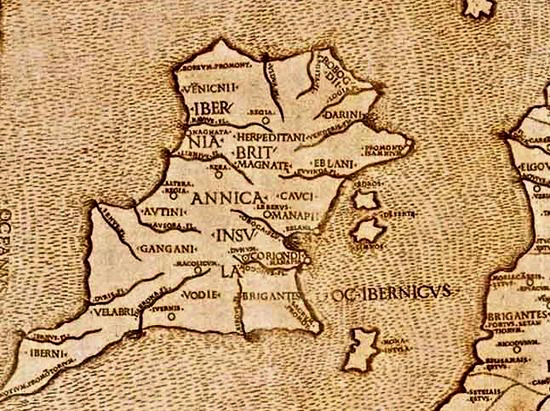

Perran-ar-Worthal (in Cornish Peran ar Wodhel) means ‘St Piran’s village by the creek’. Who is St Piran? He is the Patron Saint of Cornwall and we’ve met him before, briefly, in my account of St Ciarán, who was born on Cape Clear, and was known as ‘The First Saint of Ireland’. Even before St Patrick arrived to start his missionary work in 432 AD, St Ciarán (according to some records born in 352 AD) had been at work converting the ‘heathen Irish’. Unfortunately, his efforts were not always appreciated and Ciarán was despatched from the top of a cliff with a millstone tied around his neck! The story is elaborated by Robert Hunt FRS in his Popular Romances of the West of England first published in 1908. I have the third, 1923 edition on my bookshelves. That’s Cape Clear below: possibly the very cliff (although not at all a tall one).

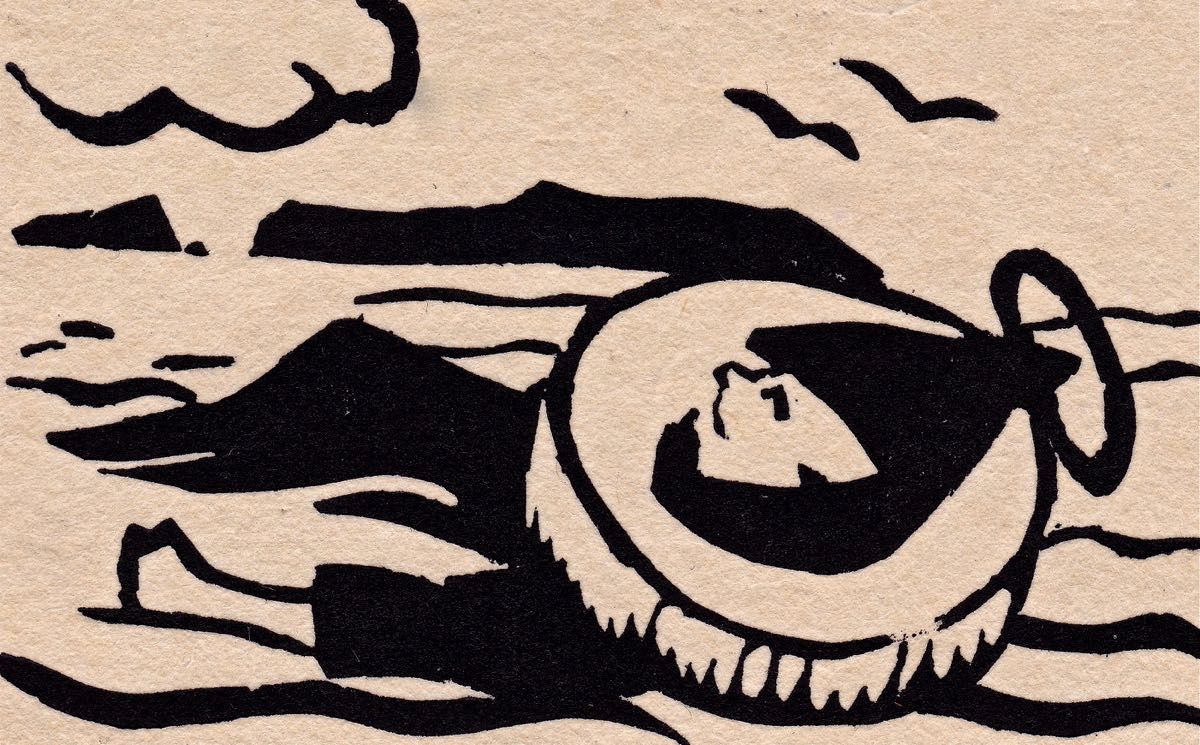

…On a boisterous day, a crowd of the lawless Irish assembled on the brow of a beetling cliff, with Ciarán in chains. By great labour they had rolled a huge millstone to the top of the hill, and Ciarán was chained to it. At a signal from one of the kings, the stone and the saint were rolled, to the edge of and suddenly over, the cliff into the Atlantic. The winds were blowing tempestuously, the heavens were dark with clouds, and the waves white with crested foam. No sooner was Ciarán and the millstone launched into space, than the sun shone out brightly, casting the full lustre of its beams on the holy man, who sat tranquilly on the descending stone. The winds died away, and the waves became smooth as a mirror. The moment the millstone touched the water, hundreds were converted to Christianity who saw this miracle. St Ciarán floated on safely to Cornwall; he landed on the 5th of March on the sands which bear his name. He lived amongst the Cornish men until he attained the age of 206 years…

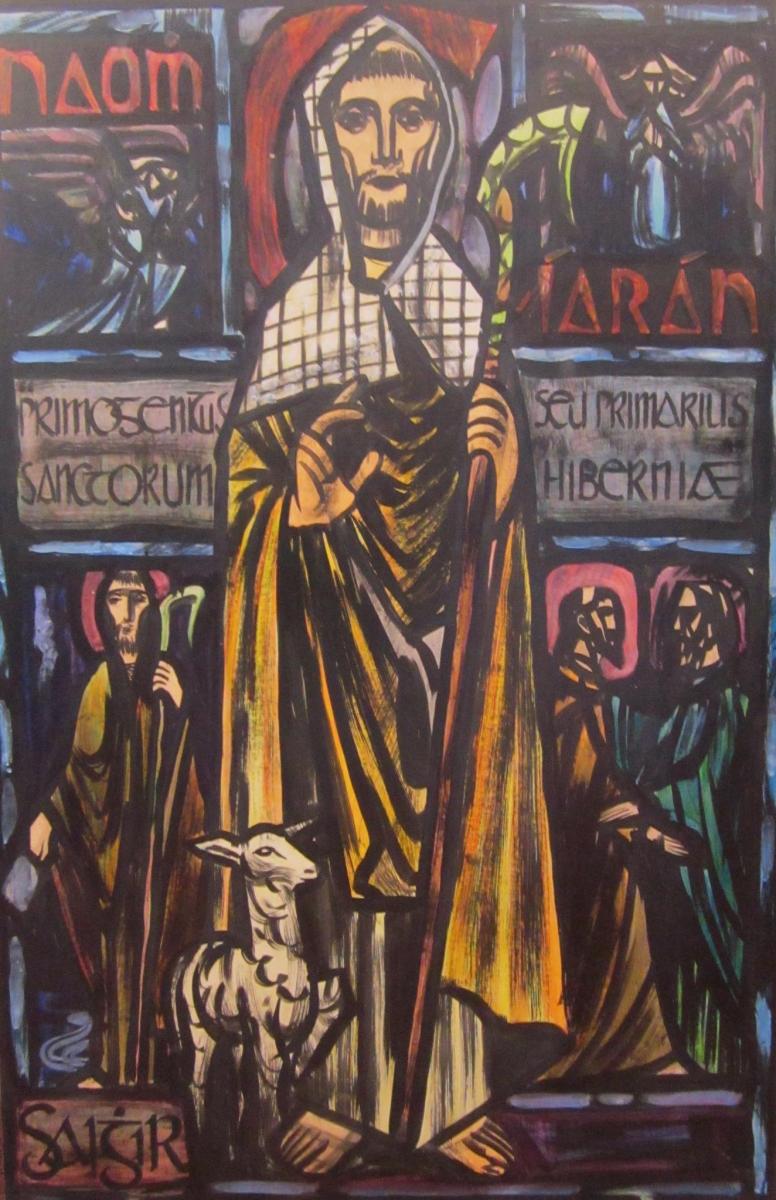

Left – St Ciarán celebrated in modern stained glass, in the church at Caheragh, West Cork; centre – Ciarán at Rath church, near Baltimore, and right – St Piran is the top figure (with church and bell) in this window panel from Truro Cathedral, Cornwall

So, what is the connection between Saints Ciarán and Piran? Apparently, they are the same person! Charles Lethbridge Kingsford reporting in the Dictionary of National Biography 1885 – 1900 (a 63 volume work!) states:

…PIRAN or PIRANUS, Saint, is commonly identified with Saint Ciaran of Saigir. The names Piran and Ciaran or Kieran are identical—p in Britain being the equivalent of the Irish k. The history of the two saints is in the main features the same, though the Irish lives of St Ciaran do not record his migration to Cornwall…

Many writers make the same assertion about the orthophony of the name but – to be fair – others, including some saintly hagiographers, do not agree, suggesting we are talking about two different saints. As someone who has a birthday on 5th March (today) – the Saint’s Day for both Ciarán and Piran – I have no doubts about the matter. Here’s another source that concurs with the view that they are one and the same saint – The Irish Ecclesiastical Record, Volume X (1874):

…The labours of St Kieran were not confined to Ireland. He passed several years on the western coast of Britain, and, as we learn from Blight’s “Churches in West Cornwall,” his memory is still cherished there. Four ancient Cornish parochial churches bear his name : these are Perran-zabuloe, or St Piran-in-the-sand; Perran-arworthal; Perran-uthnoe, situated near the coast opposite St Michael’s Mount, and St Kevern, or Pieran, which in Domesday-book is called Lanachebran. St Kieran’s holy well is also pointed out on the northern coast of Perran-zabuloe. The parish church of St Keverne stands in the district called Meneage, which terminates at the Lizard Point, the southernmost land of England. The name Meneage is supposed to mean, in the old Cornish dialect, “the deaf stone”, and the reason given for it is that, though there are several mineral veins or lodes in the district, on trial they have been found to be of no value, and hence are called deaf or useless. Tradition tells that St Kieran inflicted on the inhabitants, as a punishment for their irreligion, that the mineral veins of the district would be un-productive, and the old proverb is still handed down, “No metal will run within the sound of St Kieran’s bell”…

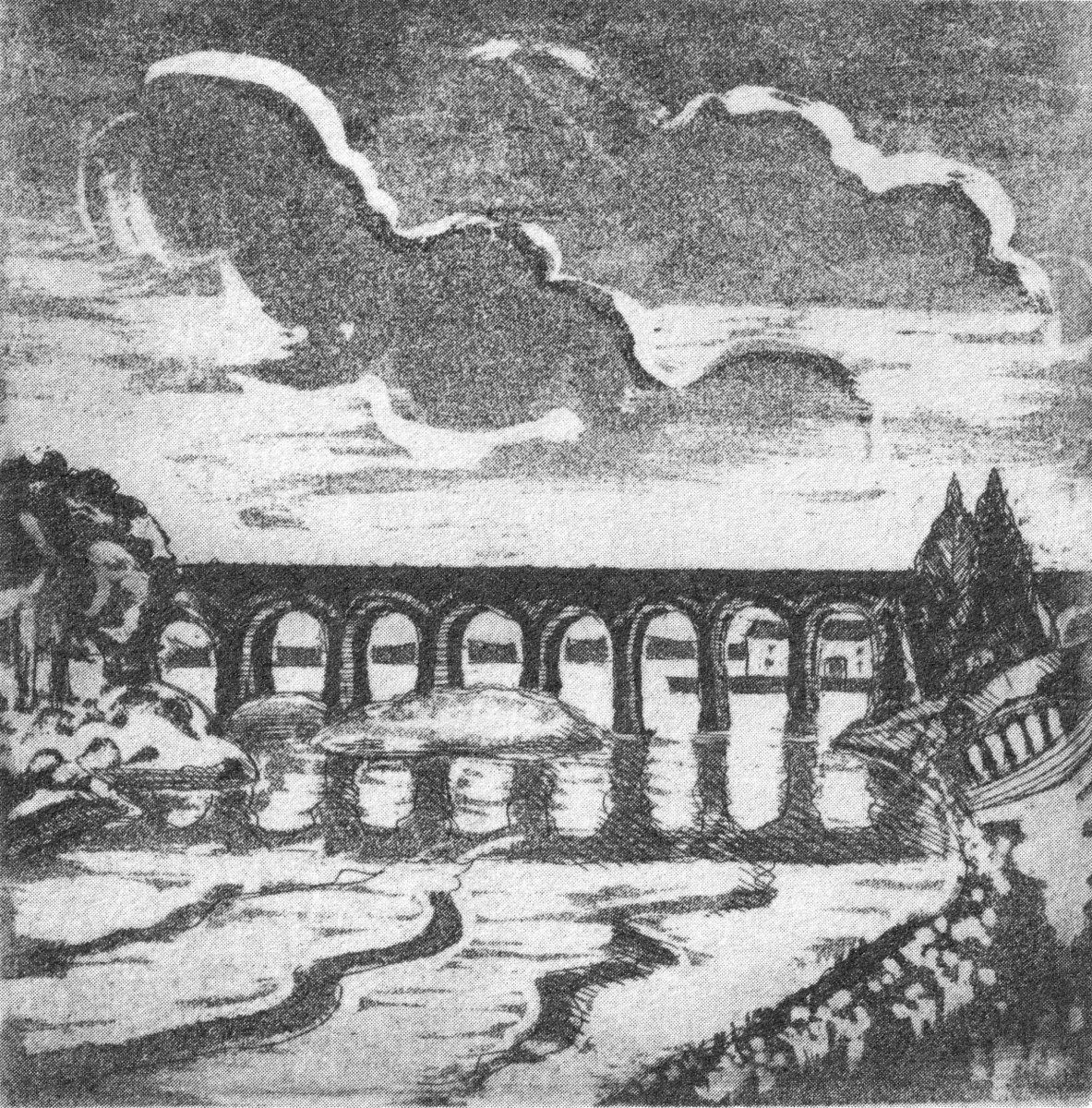

An early photo of St Piran’s Church which was built in the 12th century on the dunes at Penhale Sands, Perranzabuloe Parish, to replace the Saint’s original oratory which was buried by the shifting sands. The sands encroached on this church, too (the sands can be seen in the picture), and it was dismantled around 1800 and stone from the site was then used to build another new church two miles inland which was dedicated to St Piran in July 1805

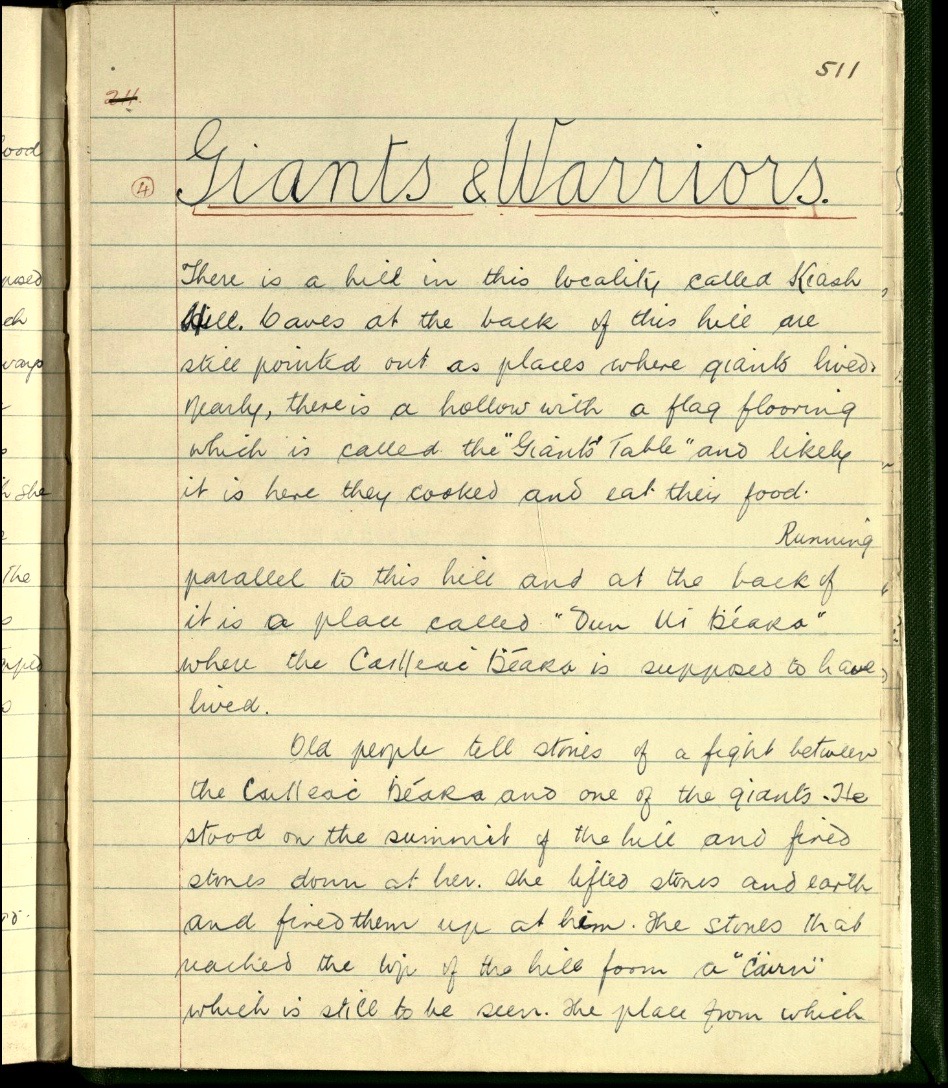

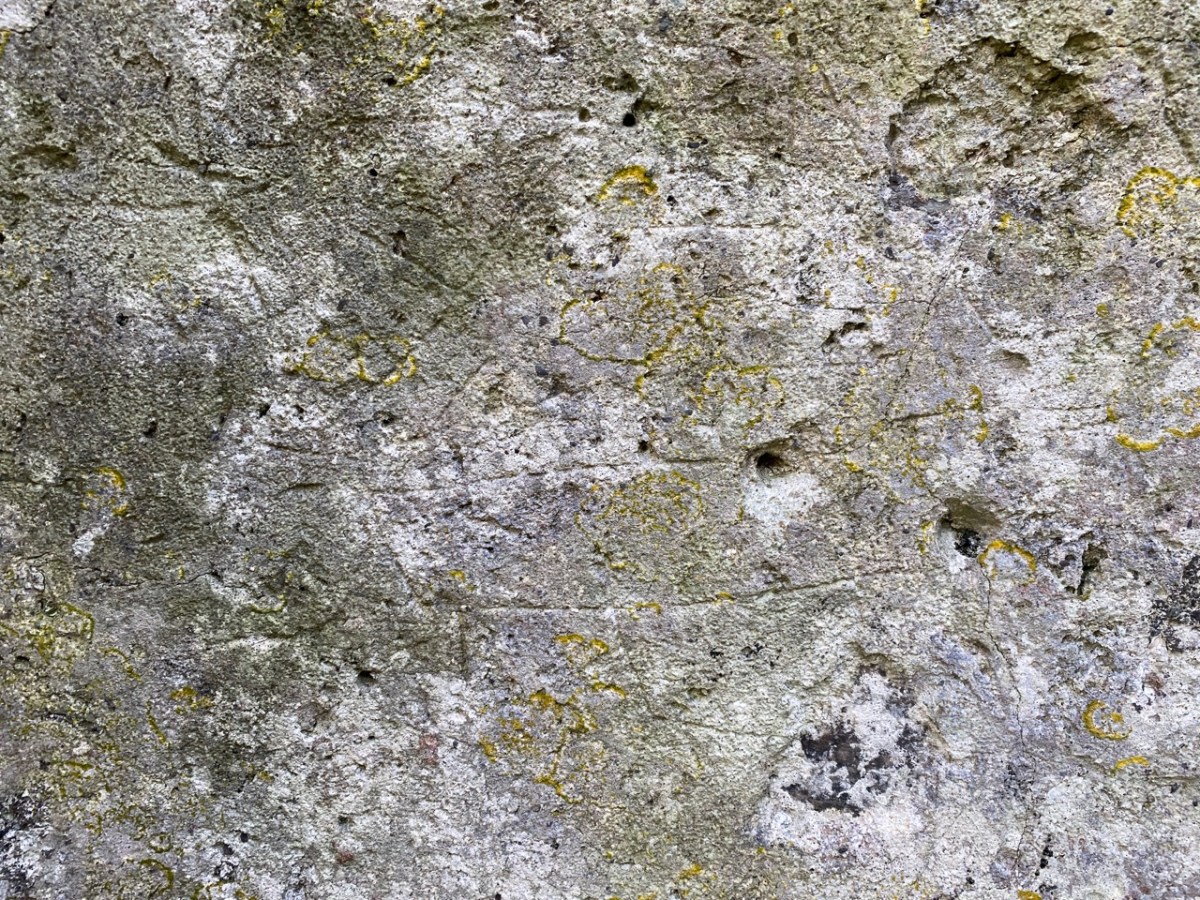

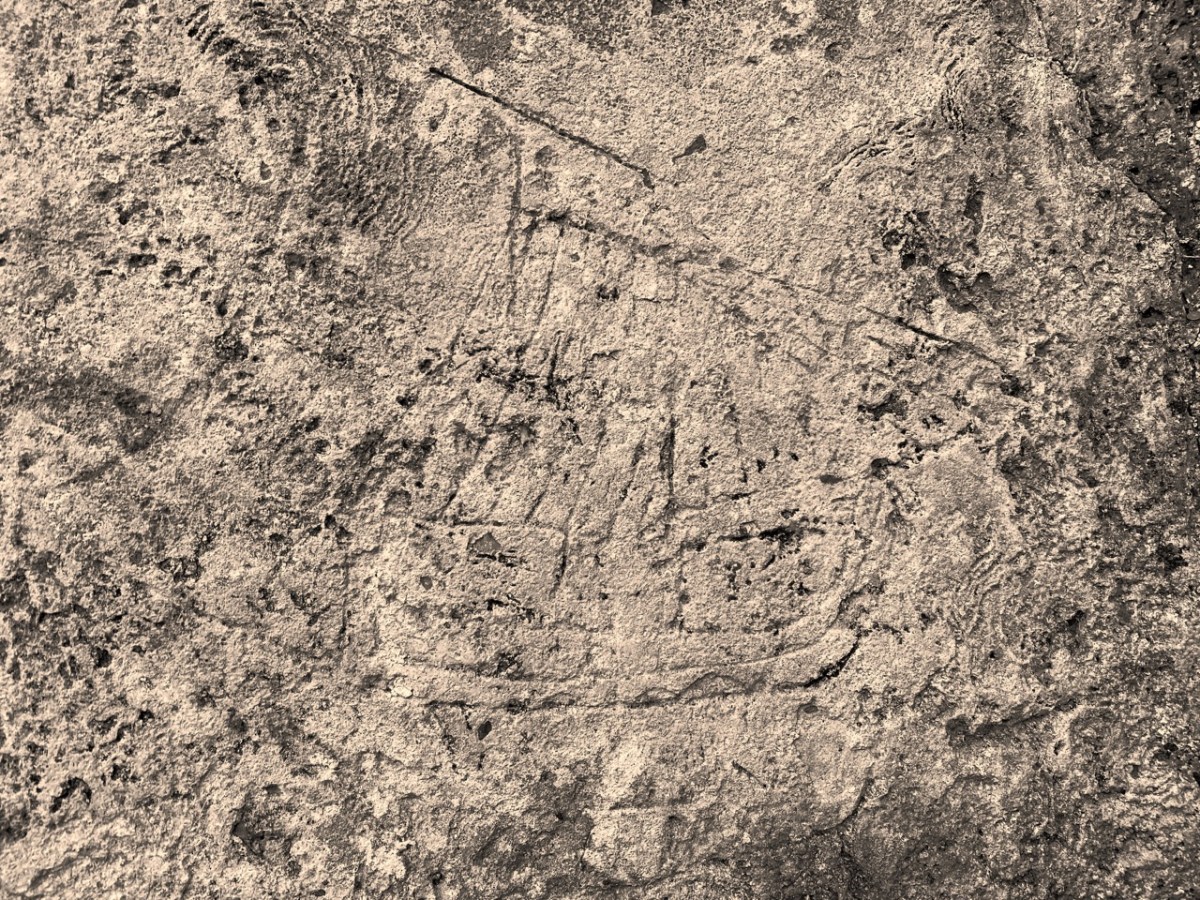

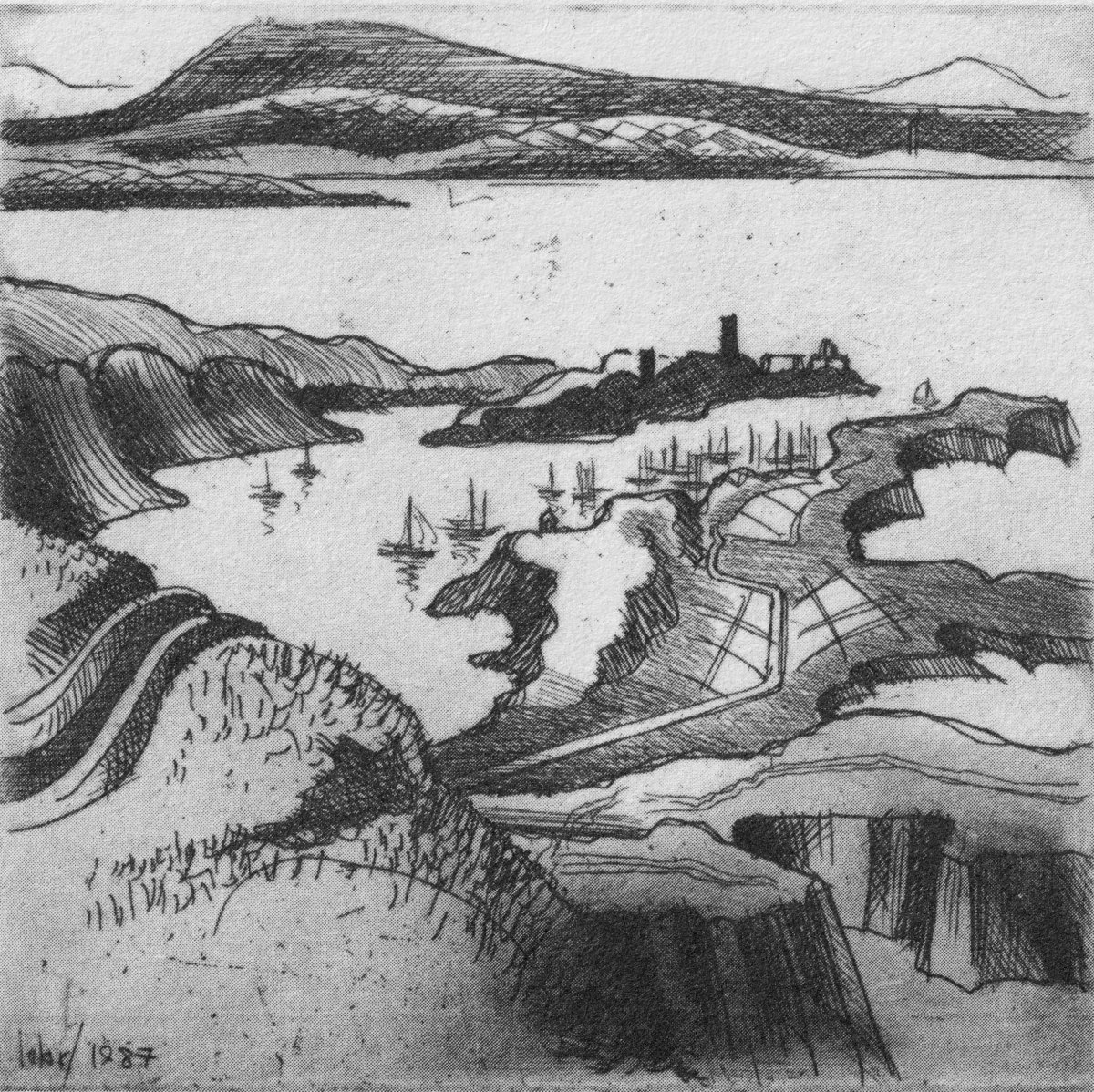

To complement that little story of the saint in Cornwall, we have to visit Ossory, an Irish diocese which encompasses parts of Kilkenny, Laois and Offaly. There they also celebrate St Ciarán of Saigir on March the fifth: he is said to have returned from Rome after years of study, firstly visiting his native Cape Clear, then commencing his travels through Ireland until his bell rang of its own accord – this happened at a small hamlet in County Offaly, now known as Seir Kieran. There he set up a foundation, the remains of which are still visible – as is a holy well, a holy bush (bedecked with clouties) the base of a round tower, the base of an ancient high cross (now holding water which has curative powers) and a holy rock which was once said to have displayed the hand print and knee prints of the saint, now completely obscured.

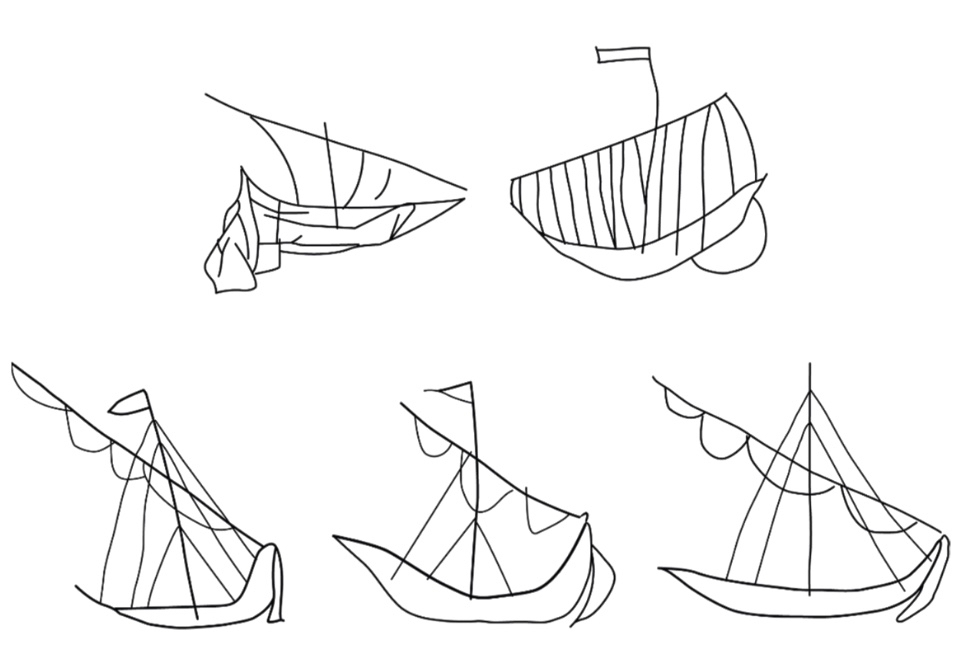

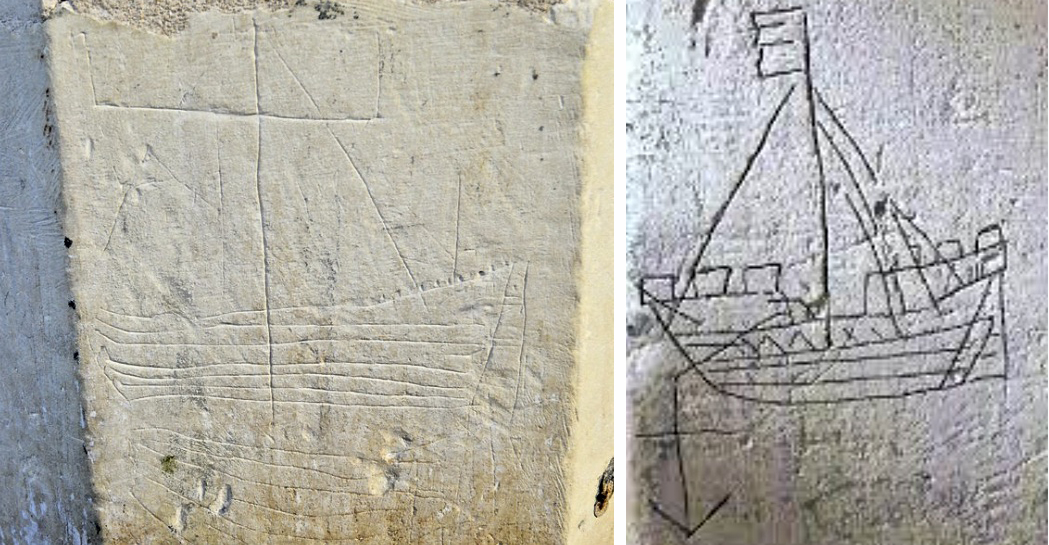

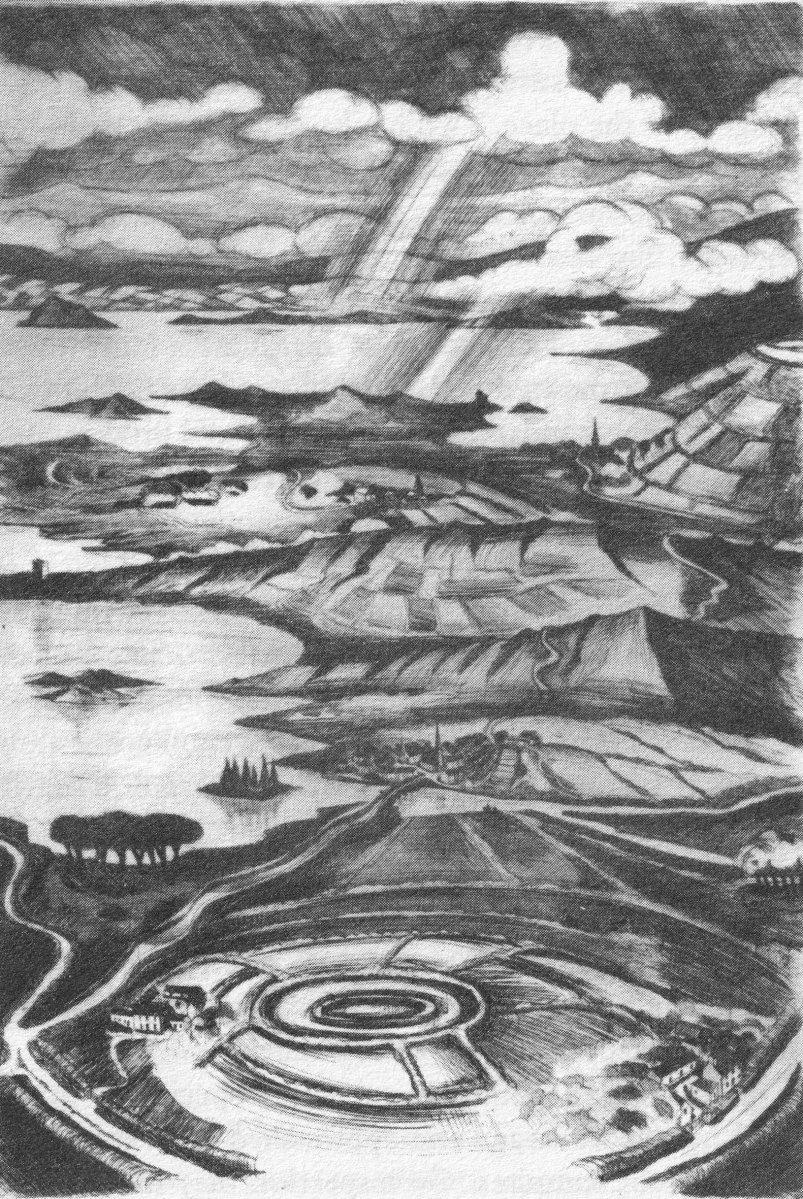

St Piran’s journey to Cornwall: “The millstone kept our man afloat” from The Discovery of Tin – a collection illustrated by Barry Cottrell

One of my favourite stories about St Piran tells of how he discovered tin smelting. He used as his hearth a piece of local stone; when he lit a fire on the hearth the veins of tin ore in the stone melted and a stream of silver ran out across the black rock, in the form of a cross. From that day to this the flag of Cornwall is a white cross on a black background, and Piran is also the patron saint of tin and tinners.

Just about now in Cornwall (March 5 2017) a great celebration is going on in honour of the saint. There will be a procession to the original oratory buried in the sands, led by the Grand Bard of the Cornish Gorsedd. Cornish flags – and the Cornish tartan – will be very much in evidence. The Cornish people have a great nationalistic spirit and have called for the 5th March to be an official public holiday. In a recent debate on Cornwall some interesting views were expressed on the place of Cornwall in a post-Brexit world, and the attributes of St Piran were symbolic of this – his inventiveness, his love of nature, and his belief in the inclusivity of all peoples in an international community.

Left – Geevor Mine, in West Penwith, one of Cornwall’s last working tin mines, now a museum of mining; right – an incarnation of the saint: Cornish author Colin Retallick stands in front of St Piran’s ancient cross on the saint’s day

St Piran lived to a great age. They say in Cornwall that he was ‘fond of the drink’ and met his end by falling into a well when walking home from a party. I hope it was a holy well! Today, seventeen centuries after St Ciarán / Piran was thrown from the cliffs of Cape Clear I am looking out to that island: …the winds are blowing tempestuously, the heavens are dark with clouds, and the waves are white with crested foam… There have been so many links between Cornwall and West Cork, ever since the Bronze Age, when Cornish tin traders brought their metal to mix with copper mined above us here on Mount Gabriel. Watch out for more posts about these links between the two communities: links which would have warmed the heart of our shared saint!

Below – St Ciarán by Richard King, painted for the Capuchin Annual in the 1950s