The fine map, above, was drawn in 1375 and is attributed to Abraham Cresques (courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division). it is known generally as the Atlas Catalan. What interests us is that it depicts two islands off the west and south-west coasts of Ireland (see detail below): Hy-Brasil and Demar. These landfalls are shown on maps since then through the centuries, the last depiction being in 1865.

We look out to the hundred Carbery Islands in Roaringwater bay. The view (above) is always changing as sun, rain and wind stir up the surface of the sea and the sky and clouds create wonderful panoramas. But, generally, the view is predictable: we know that Horse island will be across from us, and Cape Clear will always be on the distant horizon, while the smaller islets break up the surface of the ocean in-between, and help calm down its wildness when the storms come.

But, suppose it wasn’t always predictable? What if those islands changed, moved around or appeared and disappeared? It seems that such things do happen, here in Ireland. At least, they do according to some of the recorded evidence. ‘Mythical Islands’ have been mentioned by mariners and storytellers through the centuries.

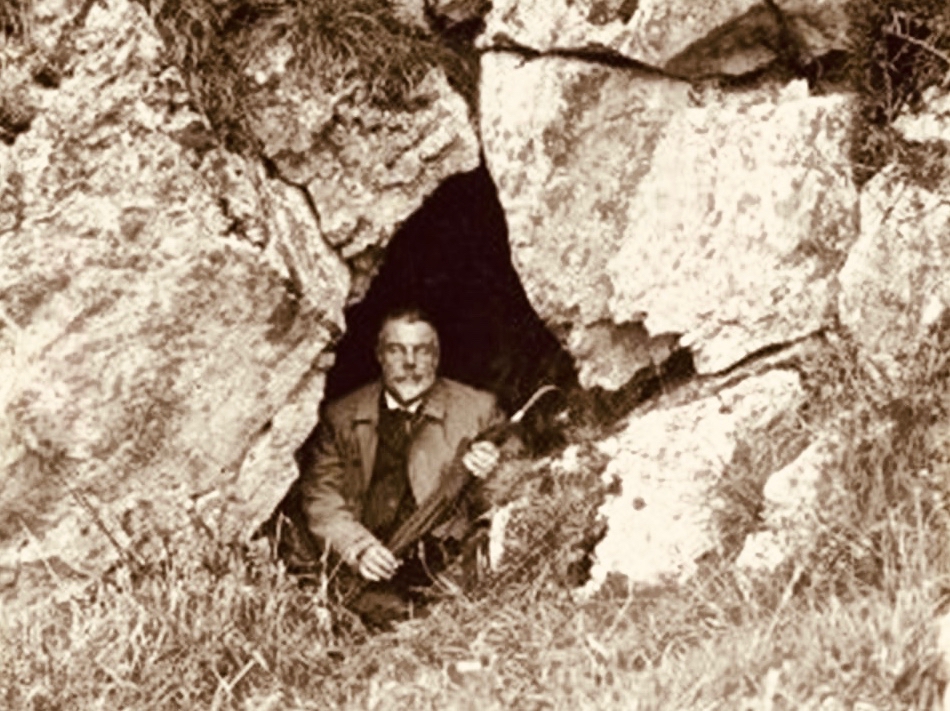

Our best source of information for Ireland’s ‘transcendent’ islands is our old friend Thomas Westropp (above, kitted out for an expedition) who was an archaeologist and folklorist living between 1860 and 1922. He was active in Counties Clare and Limerick and wrote a paper for The Royal Academy in 1912 – Brasil and the Legendary Islands of the North Atlantic: Their History and Fable. This comprehensive paper includes a list of evanescent islands, a new map drawn by Westropp, and a summary of historic maps which have located them:

Westropp’s exploration of the subject is remarkably comprehensive. Here are some extracts:

. . . Bran son of Febal, sleeping near his fort, hears sweet music, and awakes to seize a magic apple branch. An unknown woman sings of “a glorious island round which sea-horses glisten – a fair course against the white swelling surge.” In it dwells no wailing, treachery, death, or sickness; it glows many-coloured in incomparable haze, with snowy cliff’s and strands of dragon-stones and crystals. She vanishes, and Bran, with twenty-seven followers, embarks. They meet the sea-god Mananann mac Lir in his chariot, visit Magh Mell, the Isle of Laughter, and the Isle of Women, whose queen draws Bran to it by a magic clue. Entranced by love, the visitors do not note the flight of time; in apparently undiminished youth and strength they return to Ireland; it is only when the first to step ashore falls to ashes, as if centuries dead, that they know the truth. The survivors tell their tale without landing, and sail out into the deep, never to be seen again . . .

Thomas WESTROPP – Brasil and the Legendary Islands of the North Atlantic, 1912

Image above courtesy of the Worksop Bestiary.

. . . The Sunken Land. I found no name for this in north Mayo save when it was confused with Manister Ladra. Belief in it prevailed in north Erris and Tirawley from Dunminulla to Downpatrick. In 1839 it was said to extend from near Teelin to the Stags of Broadhaven and thence half way to America. A boatman knew a woman named Lavelle who saw from the shore (when gathering Carrigeen moss) a delightful country of hills and valleys, with sheep browsing on the slopes, cattle in green pastures, and clothes drying on the hedges. A Ballycastle boatman, a native of Co. Sligo, corroborated this, adding that he had seen it twice at intervals of seven years, and if he lived to see it a third time he would be able to disenchant it. He could talk of nothing else, became idle and useless, and died, worn out and miserable, on the very eve of the expected third appearance . . .

Thomas WESTROPP – Brasil and the Legendary Islands of the North Atlantic, 1912

. . . Owen Gallagher, Lieutenant Henri’s servant, heard of one Biddy Took, who, when gathering dillish (seaweed), asked some passing boatmen to put her out to an islet and fetch her back on their return : amused by her talk they brought her fishing, and soon got a ” tremendous bite.” They landed a green, fishy-looking child, quite human in shape, and in their fright let him escape and dive. The man who hooked him died suddenly within a year. Gallagher also said that he had fired at and wounded a seal; soon after, when far out to sea in his currach, he got lost in a fog-bank and reached an unknown island. An old man, moaning, with one eye blinded, stood on the shore and proved to be the seal. With more than human forgiveness, he warned his enemy to fly from the land of the seal men, lest his (the seal’s) sons and friends should avenge the cruelty . . .

Thomas WESTROPP – Brasil and the Legendary Islands of the North Atlantic, 1912

Image Carta Marina (1539) courtesy Bone + Sickle

. . . The Aran people now believe that Brasil is seen only once in seven years. They call it the Great Land. In Clare, I have heard from several fishermen at Kilkee and elsewhere that they had seen it ; they also told legends of people lost when trying to reach it. I myself have seen the illusion some three times in my boyhood, and even made a rough coloured sketch after the last event, in the summer of 1872. It was a clear evening, with a fine golden sunset, when, just as the sun went down, a dark island suddenly appeared far out to sea, but not on the horizon. It had two hills, one wooded ; between these, from a low plain, rose towers and curls of smoke. My mother, brother, Ralph Hugh Westropp, and several friends saw it at the same time; one person cried that he could “see New York ” ! With such realistic appearance (and I have since seen apparent islands in 1887 in Clare, and in 1910 in Mayo), it is not wonderful that the belief should have been so strong, probably from the time when Neolithic man first looked across the Atlantic from our western coast. It coloured Irish thought ; stood for the pagan Elysium and the Christian Paradise of the Saints ; affected the early map-makers ; and sent Columbus over the trackless deep to see wonders greater than Maelduin and Brendan were fabled to have seen, till Antilha, Verde, and Brazil became replaced by real islands and countries ; and the birds, flowers, and fruit of the Imrama by those of the gorgeous forests of the Amazon in the real Brazil. ” Admiration is the first step leading up to knowledge, for he that wondereth shall reign.” . . .

Thomas WESTROPP – Brasil and the Legendary Islands of the North Atlantic, 1912

Above is the view from our house – Nead an Iolair – a day or two ago, when a strong sea mist was coming across from the south-west, enveloping Cape Clear and making it float ethereally like one of the mythical islands. Other writers have tackled the subject of the vanishing lands, including Joseph Jacobs, who put together a collection of stories in 1919. The subject is ‘Wonder Voyages’, and the book (available online here) covers some of Ireland’s adventurers, including Máel Dúin – a predecessor of Brendan the Voyager.

Máel Dúin sets out ‘into the limitless ocean’, suggesting that ‘God will bring the boat where it needs to go’. He and his crew encounter a large number of strange islands, including:

The island of ants, from which the men flee because the ants’ intention is to eat their boat

The island of tame birds

The island of the horse-like beast who pelts the crew with the beach

The island of horses and demons

The island of salmon, where they find an empty house filled with a feast and they all eat, drink, and give thanks to Almighty God.

The island with the branch of an apple tree, where they are fed with apples for 40 nights

The island of the “Revolving Beast”, a creature that would shift its form by manipulating its bones, muscles, and loose skin; it casts stones at the escaping crew and one pierces the keel of the boat

The island where animals bite each other and blood is everywhere

The island of apples, pigs, and birds

The island with the great fort/pillars/cats where one of the foster brothers steals a necklet and is burned to ashes by the cat

The island of black and white sheep, where sheep change colours as they cross the fence; the crewmen do not go aboard this island for fear of changing colour

The island of the swineherd, which contained an acidic river and hornless oxen

The island of the ugly mill and miller, who was “wrinkled, rude, and bareheaded”

The island of lamenting men and wailing sorrows, where they had to retrieve a crewman who entered the island and became one of the lamenting men; they saved him by grabbing him while holding their breath

The island with maidens and intoxicating drink

The island with forts and the crystal bridge, where there is a maiden who is propositioned to sleep with Máel Dúin

The island of colourful birds singing like psalms

The island with the psalm-singing old man with noble monastic words

The island with the golden wall around it

The island of angry smiths

The crew voyaged on and came across a sea like a green crystal. Here, there were no monsters but only rocks. They continued on and came to a sea of clouds with underwater fortresses and monsters.

The island with a woman pelting them with nuts

The island with a river sky that was raining salmon

The island on a pedestal

The island with eternal youth/women (17 maidens)

The island with red fruits that were made as a sleeping elixir

The island with monks of Brendan Birr, where they were blessed

The island with eternal laughter, where they lost a crewman

The island of the fire people

The island of cattle, oxen, and sheep

The most well-known voyager of all – in Irish tradition – is Saint Brendan. The image above is from the Finola Window, which was crafted by George Walsh. We all know that Brendan was a real character, who discovered America back in the sixth century. On the way he also encountered many islands – which we cannot locate today (that doesn’t mean they are not there) – and had hair-raising adventures on them. This post will take you through some of his journeyings.

It’s clear that, in the shared Irish psyche, we are aware of places that we can’t always see, or visit. it’s all part of a folk knowledge that’s largely hidden away, except in the memories of older generations, that relates to the sea, and the idea that there are races of people who live on ‘lost’ islands – or even in the sea. In some of the stories about the islands it is suggested that, when they vanish, it’s because they have submerged under the ocean – perhaps temporarily.

There’s a great collection of stories readily available in a series of podcasts known as Blúiríní Béaloidis / Folklore Fragments. Look out for the one titled Blúiríní Béaloidis 16 – Otherworld Islands In Folk Tradition. I have transcribed one of my favourite pieces from this podcast, and will finish this post with it. It summarises, very neatly, the tradition that other worlds are out there, and – at times – our world and theirs meet, providing solid evidence for there being human life under the sea! The tale was collected by Dr McCarthy of Kerry.

. . . People from Dingle Harbour used to sail to Kilrush in Limerick long ago. There was a boat leaving the harbour to Limerick one day with a load of salt. There were 8 men in the boat. They had prepared the boat. There was no quay in Dingle in those days, just a slipway. A fine, strapping young man approached them carrying a pot and a pot-hook, The pot-hook looked as if it had come straight from the forge. He addressed the boat’s captain. Are you going to Limerick, my good man? I am, said the captain, we are just about to leave. Would you mind terribly, said the young man, taking me some of the way? I don’t mind, said the captain, if you wish to come all of the way. He placed his pot and pot-hook in the boat, and got in himself. They rowed away and raised the sail at the mouth of the harbour. They were halfway when the man with the pot and pot-hook roused himself. I’ll be leaving you now, he said to the captain, and I’m very grateful to you. He took hold of his pot and his pot-hook and he leapt into the sea. They never saw him again . . .

Blúiríní Béaloidis

There’s a rather nice postscript to this story:

. . . Some time later, a man with a line and hook was fishing in the sea in the same place, and a boiled potato came up on his hook . . .

Blúiríní Béaloidis