Do you remember pre-Covid days? Those times seem to bring out the nostalgia in me… It’s only two years ago that I wrote a post about our preparations – in Ballydehob – for the Wran Day celebrations that would take place on St Stephen’s Day – 26 December – following. Those festivities did happen, and we were then all in happy ignorance of how our lives were to be changed mightily by the pandemic that struck the world just a few weeks later. We’d like to think that, after all this time has passed, a level of normality will be returning. That’s not quite the case – but we are planning a ‘Wran’ this year, and today we gathered in Levis’s Corner House to make ready for it. Here’s a photo – kindly loaned by Pól Ó Colmáin – of the results of the workshop we held to prepare for the ‘Wran’ in 2019.

So firstly, here’s an abridged version of the post I put up after that workshop two years ago. I’ll follow it with an update of the equivalent [but socially distanced!] event which we held today . . .

* * * * * Back to 2019 * * * * *

Wran Hunting has featured before in Roaringwater Journal: that’s the way that St Stephen’s Day – 26 December – has been celebrated for generations in ‘Celtic’ parts of western Europe, specifically Ireland and The Isle of Man, but also in Cornwall – where it’s now only a memory – Brittany, Wales and Scotland. ‘The Wran’ is a very strong surviving tradition here, especially on the west side of the country. The Dingle Gaeltacht is the place to go if you want to see all the action (you may have to click on the bottom right of the window to turn on the sound):

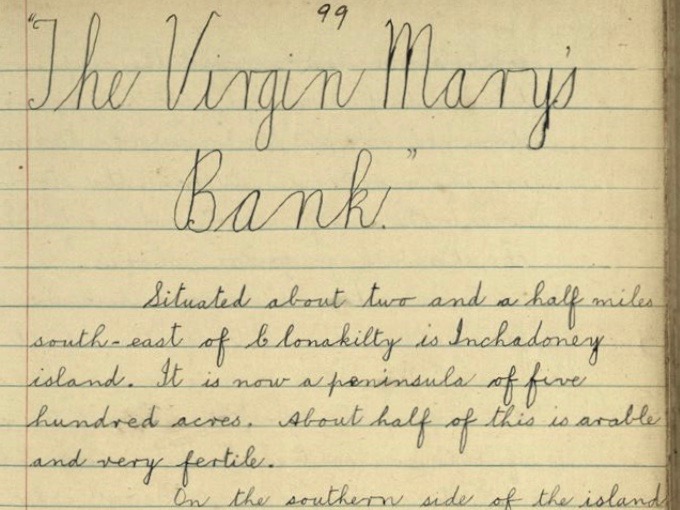

In our own Ballyedhob community ‘The Wran’ is not forgotten. In fact you can even find a poem written about it in the Duchas folklore records. This was recorded in the 1930s by John Levis, aged 32, who took it down from Jeremiah Driscoll, aged 64 years. Jeremiah had been a Wren Boy in Ballydehob. Here’s the poem:

Come all you ladies and gentlemen,

For tis here we are with our famous wran

With a heart full of cheering for every man

To rise up a booze before the year is gone.

*

Mr O’Leary we came to see,

With our wran so weak and feeble,

The wran is poor and we can’t feed him,

So we hope your honour will relieve him

*

We’ve hunted our wran three miles and more

We’ve hunted this wran all around Glandore

Through hedges and ditches and fields so green,

And such fine sport was never seen.

*

As we copied our wran again

Which caused our wran-boys for to sing,

She stood erect and wagged her tail,

And swore she’d send our boys to jail.*

As we went up through Leaca Bhuidhe

We met our wran upon a tree,

Up with a cubit and gave him a fall,

And we’ve brought him here to visit you all.

*

This the wran you may plainly see,

She is well mounted on a holly tree,

With a bunch of ribbons by his side

And the Ballydehob boys to be his guide.

*

The wran, the wran, the king of all birds,

St Stephen’s day he was caught in the furze,

Although he is little, his family is great,

So rise up landlady and fill us a treat.

*

And if you fill it of the best,

We hope in Heaven your soul will rest,

But if you fill it of the small,

It won’t agree with our boys at all.

*

To Mr O’Leary and his wife

We wish them both a happy life,

With their pockets full of money, and their cellars full of beer,

We now wish a merry Christmas and a happy New Year.*

And now, our song is ended, we have no more to say,

We hope you’re not offended for coming here today,

For coming here this morning we think it is not wrong,

So give us our answer and let us all be gone.

Traditional, DUCHAS

By good fortune there’s ‘Mr O’Leary’ above! He’s the landlord of Levis’ Corner House Bar in Ballydehob: he allowed the Wran workshop to take over his pub yesterday. Basically that involved covering the whole place in straw out of which, magically, appeared lots of wonderfully crafted Wran masks. Joe is wearing a fine example.

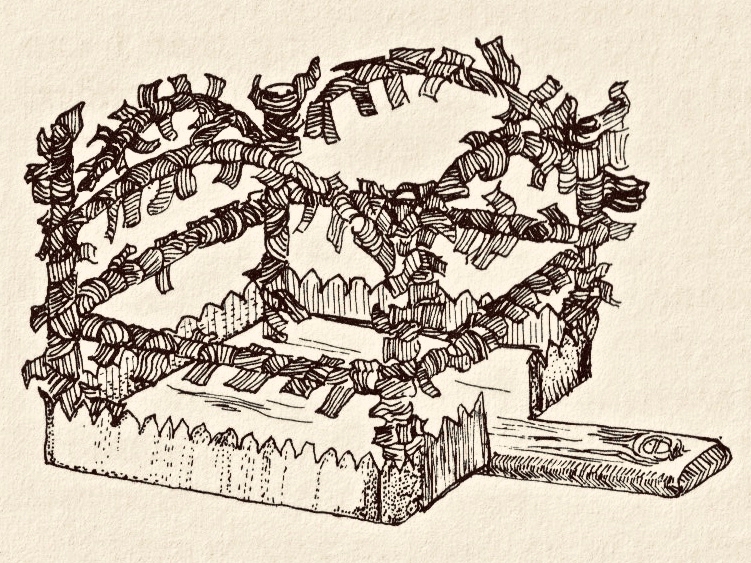

Finola and I were at the workshop, and there I am with work in progress on the straw mask which we made (upper picture). You’ll notice that I’m wearing ‘tatters’: I’ve had these for years, and I used to don them for our own mumming tradition in Devon which also happened on 26 December (that’s me with the squeezebox mumming in the 1970s! – lower picture). Over there we called St Stephen’s ‘Boxing Day’ because that was when ‘Christmas boxes’ were given to the postman, the milkman and anyone else who provided their services through the year. Interestingly, Kevin Danaher mentions the ‘Wran box’ which was taken around the houses by the wrenners (or Wran Boys) and used to collect money ‘for the Wran’. This illustration of a Wren box from County Galway is from Danaher’s book The Year in Ireland:

The workshop in Levis’ was very well attended, and there is clearly great enthusiasm for reviving this custom. Sonia collected the straw at the annual Thrashing in Ballydehob – which is a traditional harvest celebration. It’s not easy to find the right straw for making the masks nowadays: anything that has been through a combine harvester has been flattened and will not survive the plaiting.

It’s a complex process, but the group coped well in acquiring the new skills under Sonia’s tutelage. The making – every year – has always been part of the tradition where it’s still practised today. Sometimes the straw masks (which are only one part of the ‘disguise’) are destroyed after Stephen’s. In some of the Dingle traditions they are ritually burned on the following St Patrick’s Day.

* * * * * * Fast Forward to 2021 * * * * *

Two years later, on a damp Sunday in Ballydehob, you might have seen the strange sight of bundles of straw being transported across the road to Levis’, where the 2021 Wran Workshop is about to take place in the ‘outback’ area of the bar. That’s Sonia (on the left above) who is masterminding the whole proceedings, and also oversaw the growing of the straw.

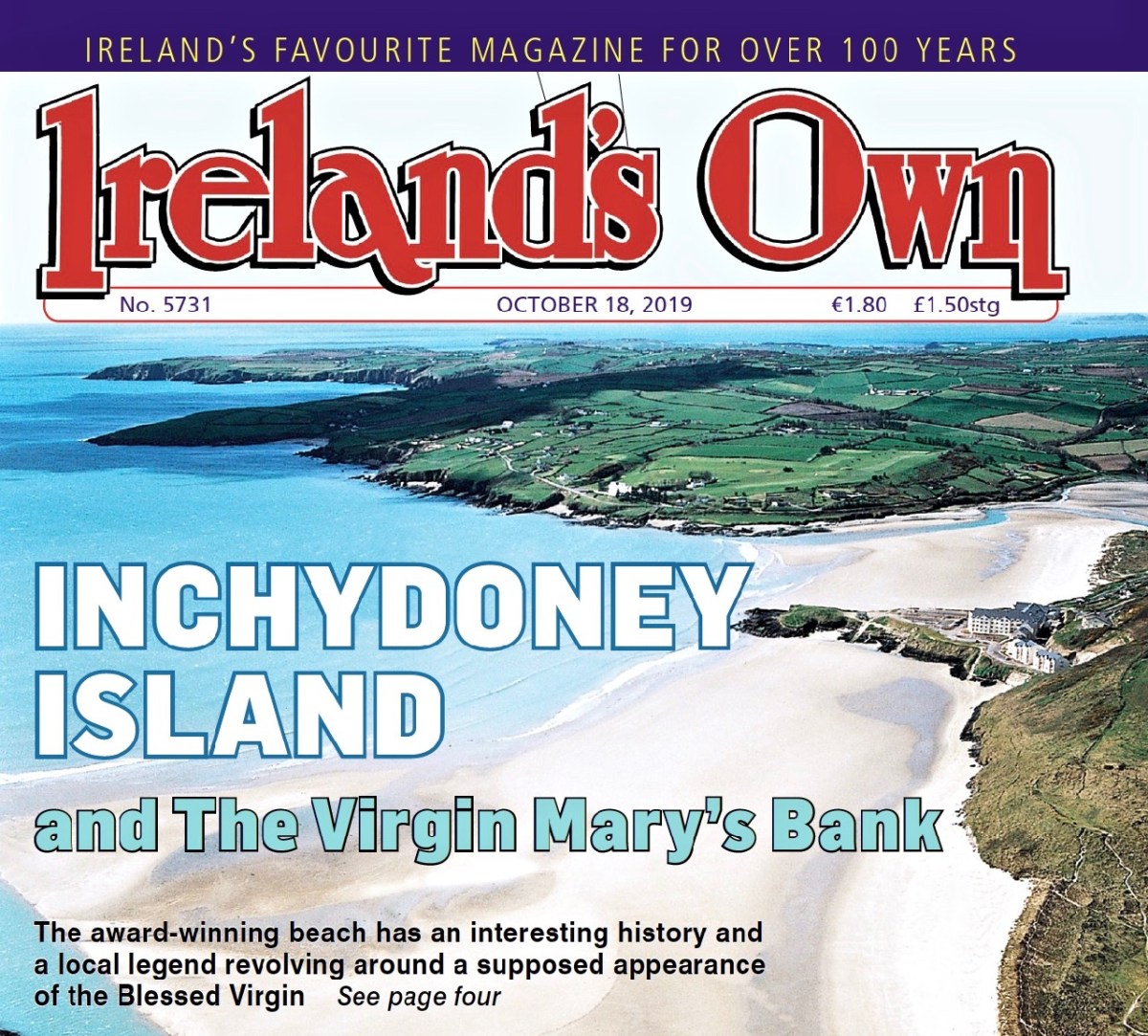

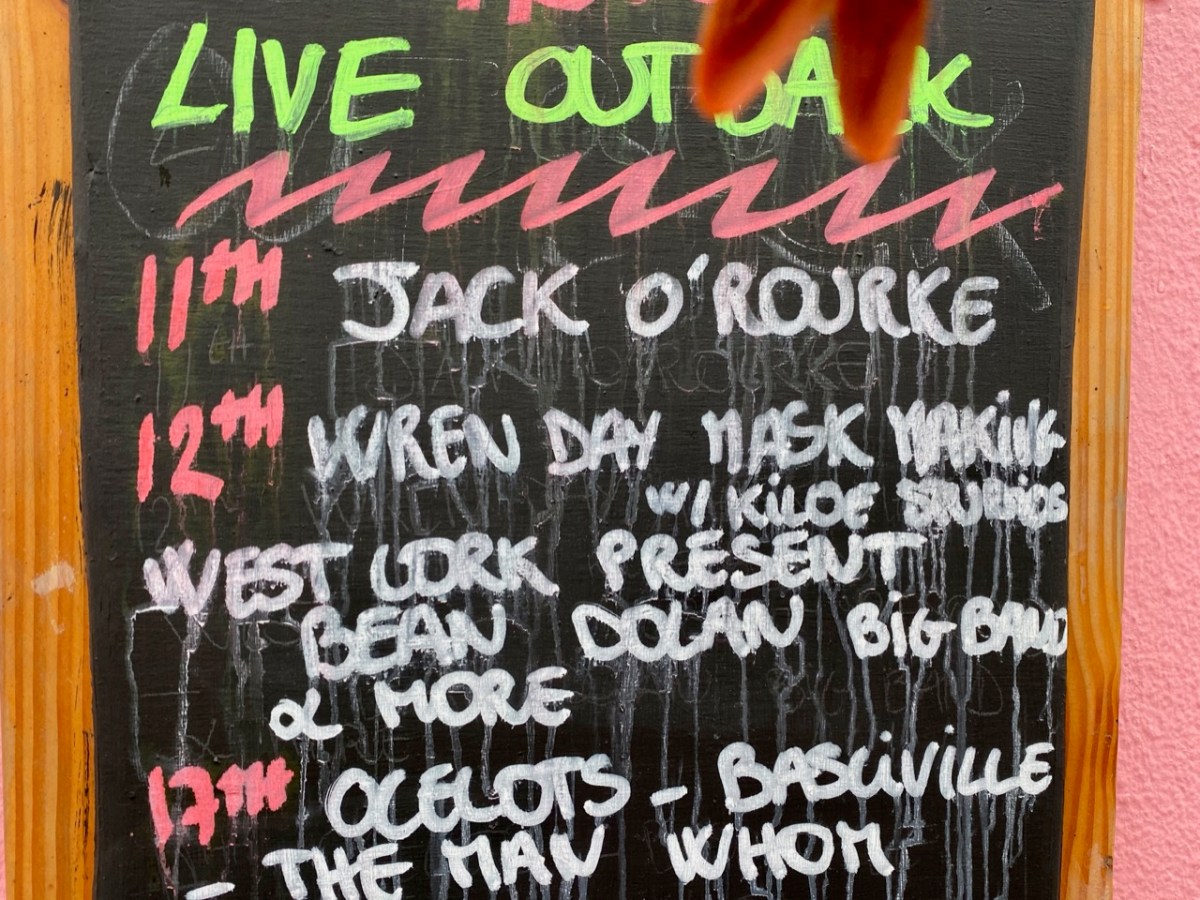

We all really appreciate Joe and Caroline – who run Levis’s – who are so supportive of community events and who, like everyone else, have had to struggle to keep business going through the ups and downs of Covid restrictions. The ‘Outback’ – formerly their yard – has been remarkably transformed into a comfortable outdoor venue, and live concerts and events are continuing through the winter season, helping to make our days seem as normal as possible.

We were a small but dedicated group, determined to get the tradition going again in Ballydehob. We are not sure, yet, when it will happen. Traditionally it should be Stephen’s Day, but it all depends on how available the participants will be. We will keep all our readers fully informed! meanwhile, if you need encouragement, look at the work that has gone into the straw masks this year . . .

Here’s Sonia Caldwell again, above. We have featured her Kilcoe Studios in a previous post. She is undoubtedly the energy behind this project. Look out for us all shortly after Christmas – there is good entertainment to be had. But, also, essential traditions to be kept alive to ensure that our world keeps turning!

That’s Pól Ó Colmáin, above, testing out his mask for size before finishing off the conical headpiece. Marie and he run the Working Artist Studios in the main Street of Ballydehob – a wonderful addition to our village’s thriving assets. Pol also bravely works away at teaching the Irish language to a number of students, including me! Here are both of them this afternoon with their completed Wran Day pieces – and also my own mask back at home . . .