In our travels we always have an eye open for signposts, especially those that point down leafy, narrow boreens: there’s probably some piece of almost lost history at the end of every one. We were beckoned, last week, by a fading cast iron plate written in ‘old Irish’ – Reilig – and the English word Cemetery. It was in a remote spot, and indicated a long, green lane with a gate in the distance. There had to be something there for us!

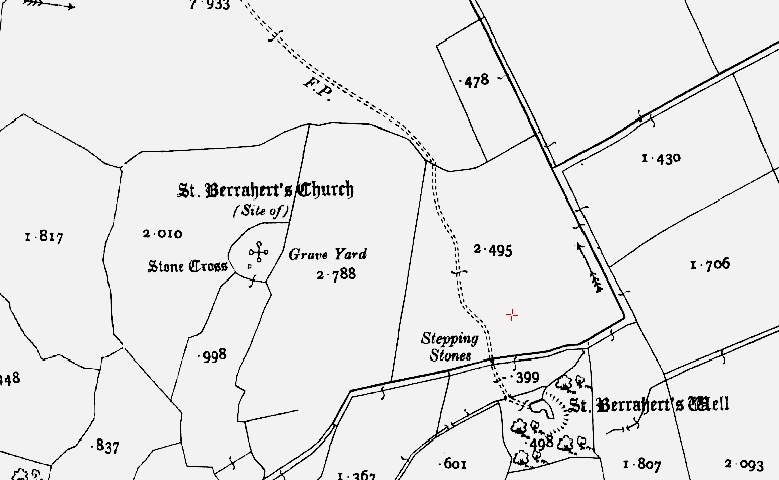

We were in West Cork, just by the little harbour of Glandore (in Irish Cuan D’Ór – Harbour of Gold). The green boreen took us down to an old burial ground which surrounds the ruins of a church dating, probably, to the 12th century. Around this are ancient stones – marked and unmarked – which signify the resting places of generations. It seems an idyllic place to rest, right off the beaten track, with only the sounds of nature to enhance the peace.

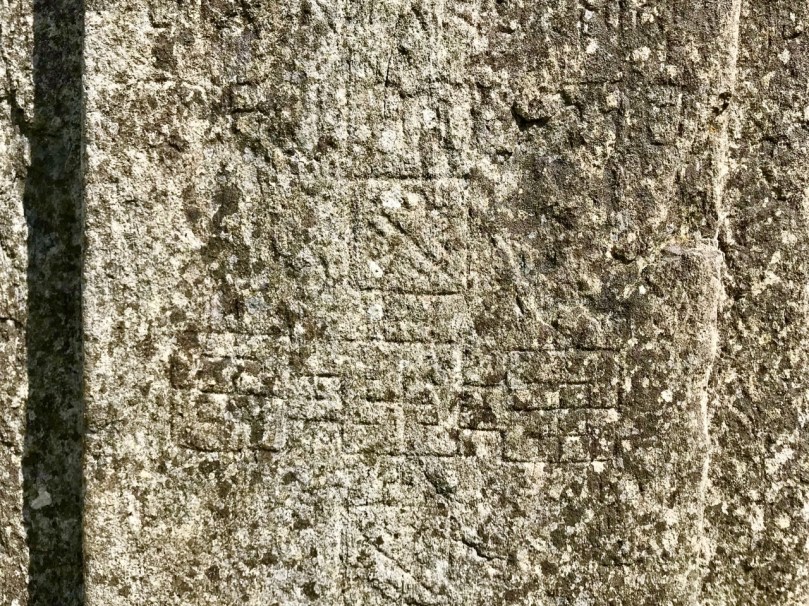

‘As quiet as the grave’ might be an apt expression in this place where we spent half an afternoon and saw no living soul. But the physical evidence of those who had passed was constantly fascinating. In Ireland, the simplest of grave markers is just an undressed stone firmly embedded in the soil. To us, they look random and rough, but it is said that every stone is chosen for a particular shape which is always remembered by the family who set it, and who passed the knowledge on – no markers were needed as long as that memory continued. Other stones are inscribed, although these are fewer – and some are particularly fine: a Celtic cross which dates to 1931, for example.

So far, our explorations in the Old Cemetery were typical of many another burial ground, but as we walked around the back of the ruined church we were astonished to see something we have never come across before in Ireland – a large pyramid!

You get a sense of the scale of this construction by the figure in the picture above. No Giza, perhaps, but nevertheless something monumental and unexpected in this out-of-the-way corner of West Cork. It isn’t alone, as right next to it is another mausoleum (for a mausoleum is the pyramid’s purpose): an ivy-clad masonry stronghold, huge and impenetrable.

The two vast tombs stand side by side (above) in an odd juxtaposition. We scratched our heads in wonder and searched for clues of names and dates while we were there in the churchyard and, later, in records online. Very little is revealed. There are several inscriptions set on carved stone plaques on the pyramid – all impossible to read because of the moss and lichen growth. Over the iron doorway is a lintel inscribed with – I believe – the name John Hussey de Burgh.

Later searches revealed the following:

. . . John de Burgh was born on 10 June 1822 and died 25 April 1887. Page 159 of The Calendar of Wills and Administration 1858-1922 in the National Archives of Ireland records that the will of “John Hamilton Hussey de Burgh late of Kilfinnan Castle Glandore County Cork Esquire”, who died on 25 April 1887 at the same place, was proved at Cork on 6 July 1887 by “Louis Jane de Burgh Widow and FitzJohn Hussey de Burgh the Executors”. Effects £1,246 11s 1d . . .

Kilifinnan Castle (a replacement built on the site of a structure dating from 1215) is a short distance to the south of the old cemetery, and it is highly likely that John Hamilton is the de Burgh commemorated on the pyramid. Apparently, he had seven children so it is likely that at least some of the other plaques would refer to these. The large stone-block tomb was giving up no secrets, with no apparent entrance and no plaques. There are signs that the burial ground is still visited and kept tidy.

We had to tear ourselves away from Glandore’s Old Cemetery: it is a beautiful and peaceful place. We didn’t much increase our knowledge of the history of the settlement itself, although the 1861 C of I Christ Church (Kilfaughnabeg – The Little Church of Fachtna) above the bay has a display of local lore and tales and is in any case well worth a visit: the only approach to it is through a tunnel hewn from a rock face.

Our explorations in the Reilig left us with questions to be answered: not least, what was the inspiration for the pyramid, which seems so alien in far away West Cork?