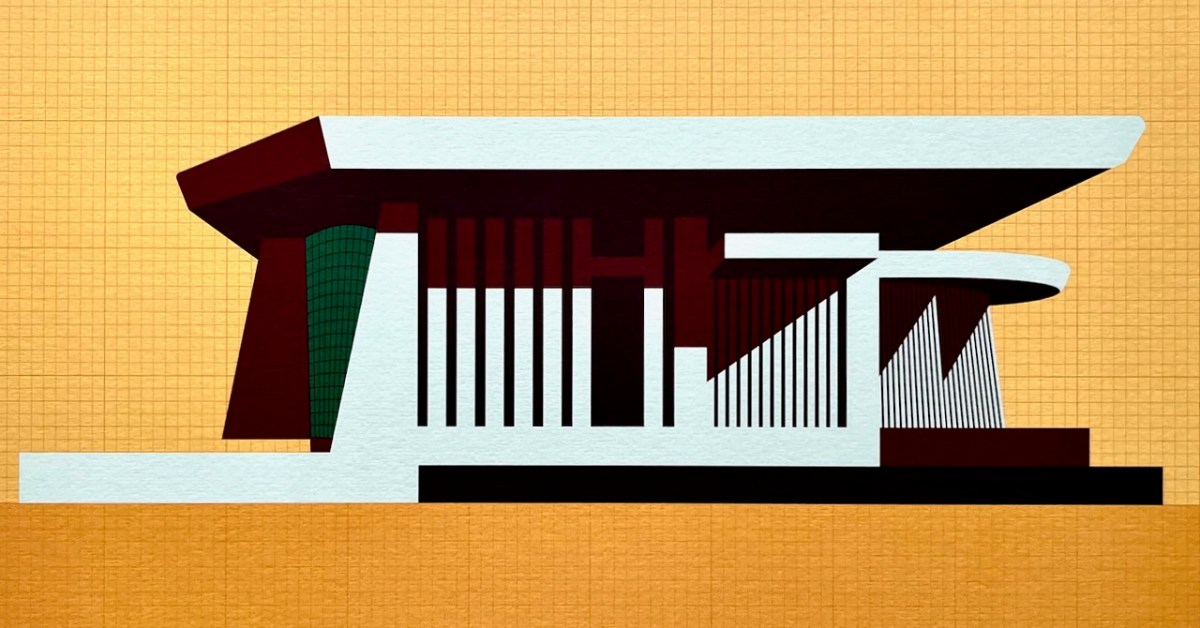

This is my favourite image of the year! I published a post about the architecture of Bantry Library, and it proved to be our most popular . . . This limited edition print, a collaboration between Dermot Harrington of Cook Architects and Robin Foley of Hurrah Hurrah is celebrating the upcoming 50th Anniversary of the completion of Bantry’s Library in 1974, and some refurbishment work is being undertaken for the occasion. For me, the print captures perfectly the iconic graphic of this most unorthodox design.

We both wrote 52 posts this year, each of around 1,000 words, and all fully illustrated. Above is a pic of one of the penstocks which brings the water into the turbine casings at Ardnacrusha Power Station (courtesy of ESB Archives). This incredible engineering feat – well ahead of its time – was constructed between 1925 and 1929, and was integral to the supply of electricity throughout Ireland’s young state by harnessing water power from The Shannon. West Cork benefitted from Rural Electrification, and I thoroughly enjoyed researching and writing a series of posts on the whole subject.

. . . Once a community was connected, or about to be connected, the ESB held public demonstrations of household appliances. These were then sold bringing electric irons, kettles, stoves to homes. The demonstration evening in Glenamaddy was held in January 1951. The handwritten report records that it took place “in the very fine Esker Ballroom”; these events were social occasions that brought communities together. The Glenamaddy evening “was attended by about 90, including 50 women. As is usual, the women appeared to be more keen than the men and more inclined to ask questions (and to argue). After the demonstration, a melodeon player turned up and an impromptu dance got under way” . . . Small towns and rural townlands became brighter and winters less harsh and Christmas more special as the fairy lights began to shine. It also gave rise to a rural Irish icon as every house had the Sacred Heart picture with the (electric) red lamp (below): many didn’t get a kettle and washing machine until later on . . .

ESB Archives

The whole series on Rural Electrification was written during the summer and can be read through this link: https://roaringwaterjournal.com/tag/electrification-of-ireland/

Since 2018 our own Museum in Ballydehob has been showing exhibitions of the work of locally based artists. This year it was the turn of the Verlings – John and Noelle. John died, sadly, in 2009; Noelle is still alive and kicking and assisted Brian Lalor and myself in assembling an excellent collection of the work of these two creative residents of our village, assisted technically and ably by Stephen Canty. BAM is a really valuable resource in setting out the unique history of the artistic community here in West Cork from the 1950s onwards.

A wonderful photograph (courtesy Geoff Greenham with many thanks) of St Bridget’s Catholic Church in Ballydehob. The interior was reordered by John Verling.

. . . The gold fish hand drawn in the background of the altar and the depiction of one fish swimming against the shoal continues to evoke admiration from locals and visitors alike. He also designed the two ‘windswept thorn’ stained glass windows and etched the brass surround of the tabernacle. The Altar slab, composed of a vast monolith like the capstone of a dolmen, is a distinguished piece of sculpture and a tribute to his imaginative capacity . . .

JOHN VERLING WEBSITE: HTTPS://WWW.JOHNVERLING.COM

There was great drama off the coast of Ballydehob on the night of 22 September 1973, and its 50th anniversary was duly celebrated in Roaringwater Journal!

. . . AS an inspector from the aeronautical section of the Department of Transport and Power arrived in Ballydehob to begin an investigation into Saturday night’s plane crash off the Cork coast, it was learned last night that the pilot of the Piper Cherokee almost lost his life in his efforts to save the other three men on board. Michael Murphy (23), of Mercier Park, Curragh Road, Cork, who was sitting next to the pilot, Eric Hutchins of Ballinlough, Cork, said that Mr Hutchins was concentrating so much on getting the plane down that he was knocked unconscious at impact. Mr Murphy, together with Noel O’Halloran, of St Luke’s, Cork, and James McGarry, of Monkstown, Co Cork, had been braced for the crash and scrambled free on to the wing. But then they found that they could not get out Mr Hutchins who was unconscious. Mr O’Halloran then went back into the rapidly sinking plane and between them they pulled Mr Hutchins free and threw him into the water. The three men then swam ashore taking 40 minutes to reach land at Fylemuck, as they had to support the injured man all the way . . .

IRISH PRESS, MONDAY 24 SEPTEMBER 1973

All four crew and passengers on the plane survived the ditching, but the aircraft itself (a photo taken in its good days, above) was a write-off. Those living locally who remembered the event gathered to mark it in Schull, on the anniversary.

That’s Keith Payne, above. He’s one of the many artists who has lived in West Cork for a significant part of his life – at Leamcon, and he was deservedly given an exhibition in The Blue House Gallery, Schull, in September this year. He has always been fascinated by ‘early markings’, including Rock Art: he contributed dramatically to our own Rock Art exhibition at The Public Museum, Cork, in 2015.

That’s a spectacular large canvas by Keith inspired by Rock Art at Derreenaclogh, West Cork (on the right, above). It’s from an earlier exhibition by Keith in County Clare in 2018, at the Burren College of Art Gallery in Ballyvaughan, Co Clare. The work below is titled Cave Entrance.

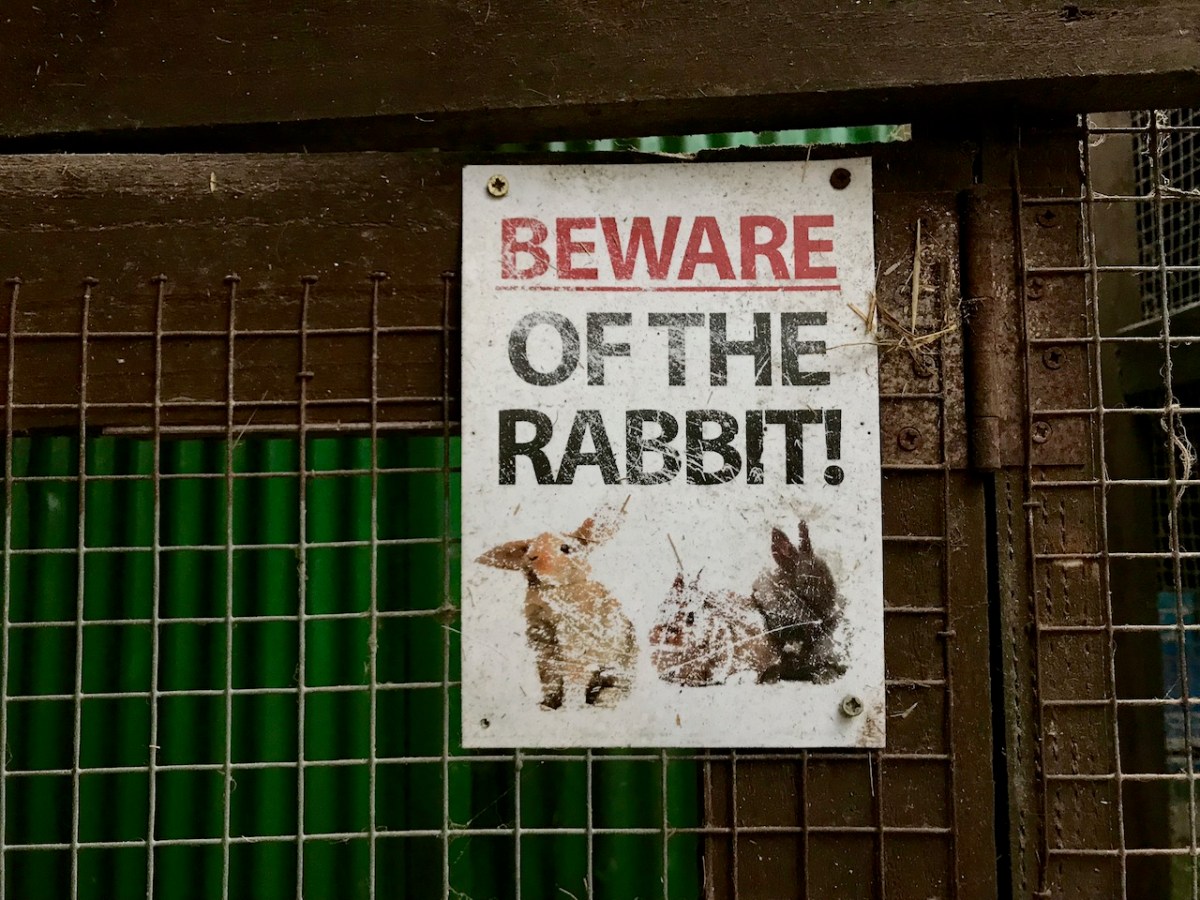

Throughout the year I continued to publish posts on some of my favourite subjects: Irish signs, advertising and curiosities. I’m always avidly collecting these, and will have some to show in 2024, for sure. In the meantime, let’s hope our general news becomes more positive as we move forward in this disorienting world of ours . . . Have a good new year, everyone!

And here’s a little PS . . . Way back in January, before I had the idea to write about Rural Electrification in Ireland historically, I penned a post about how I saw Ireland very much at the forefront of harnessing wind power – all at sea. Here it is!