All across West Cork, at higher elevations, autumn heralds the emergence of vast carpets of amber grass. Shading from yellow to red and everything in between, it is the distinctive colour of the uplands. We call it Fionnán (pronounced fyuh-nawn).

Fionnán is a particularly apt name because the root, fionn, means blonde, but fionnadh can mean shaggy animal hair. In English, this is the far less romantic and puzzling Purple Moor Grass. Actually, when it’s young, the first spikes can have a purplish hue, but that colour certainly does not spring to mind in the autumn. In Latin, it’s Molinia caerulea – Molinea after the man who named it, a Chilean naturalist, and caerulea meaning blue. Right – that’s more than you wanted to know about the name.

A Fionnán and Rush pasture is a recognised and important habitat, and should be rich in wildflowers, sedges, and other grasses. But it’s a delicate balance that can be upset by a number of factors – too much or too little drainage, under- or over-grazing, grazing by the wrong animals, and too-frequent burning.

Burning and over-grazing by sheep have affected many of our Fionnán pastures in West Cork. Repeat burning (often done in the belief that it improves grazing and gets rid of gorse) in particular allows the Fionnán and bracken to take over at the expense of other species and in the end degrades the soil.

Birdwatch Ireland says that the answer is sustainable grazing levels to keep certain bog grasses in check, such as Purple Moor Grass (Molinia caerulea). Too little grazing and the grasses can become rank, smothering the important bog mosses, heathers and sedges. This reduces the species diversity and the ability to be an active, peat-forming bog.

On our walk this week it was difficult to assess the health of this particular pasture, since nothing much is still blooming. However, I have walked it before and am happy to report that I have noted many of the species that are indicators of a healthy moor-grass pasture – Meadow Thistle, Heath spotted-orchid, Lousewort, and Cross-leaved Heath.

To walk in a Fionnán pasture is a deeply pleasurable experience. There is something about being surrounded by waving expanses of golden grasses – perhaps Sting’s Fields of Gold was influenced by such an experience. The weather has been very variable but we did manage to catch some sun, and evade the inevitable downpour by getting back to the car in the nick of time.

As I said, not a lot was still in bloom – except the gorse because, you know, when gorse is out of blossom, kissing’s out of fashion. But there is still lots to see and sense. Chamomile grows abundantly along the track and its heady scent drifts upwards as you tramp over it.

Old fence posts still hang on, with their rusted barbed wire still attached, along with lichens. I was especially delighted to see Devil’s Matchstick lichen on one of the old posts.

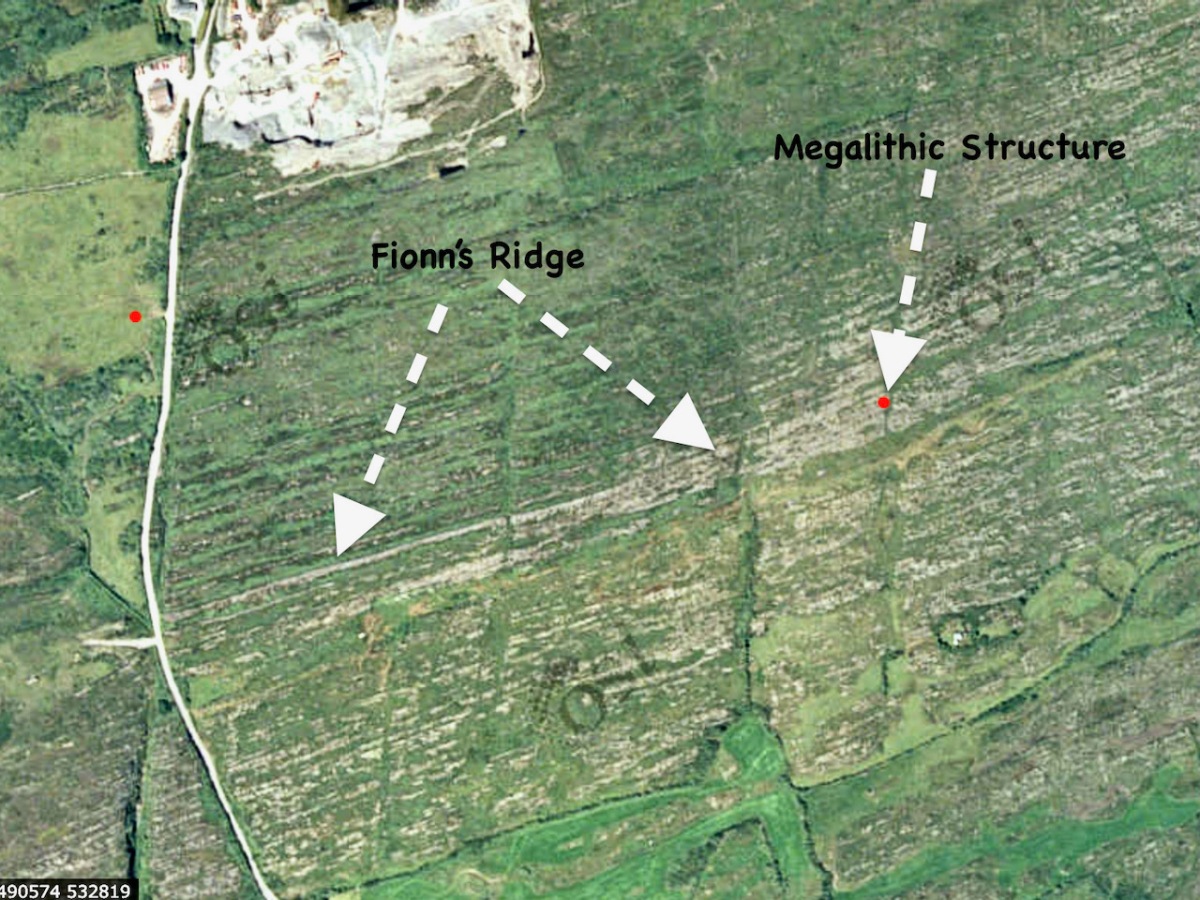

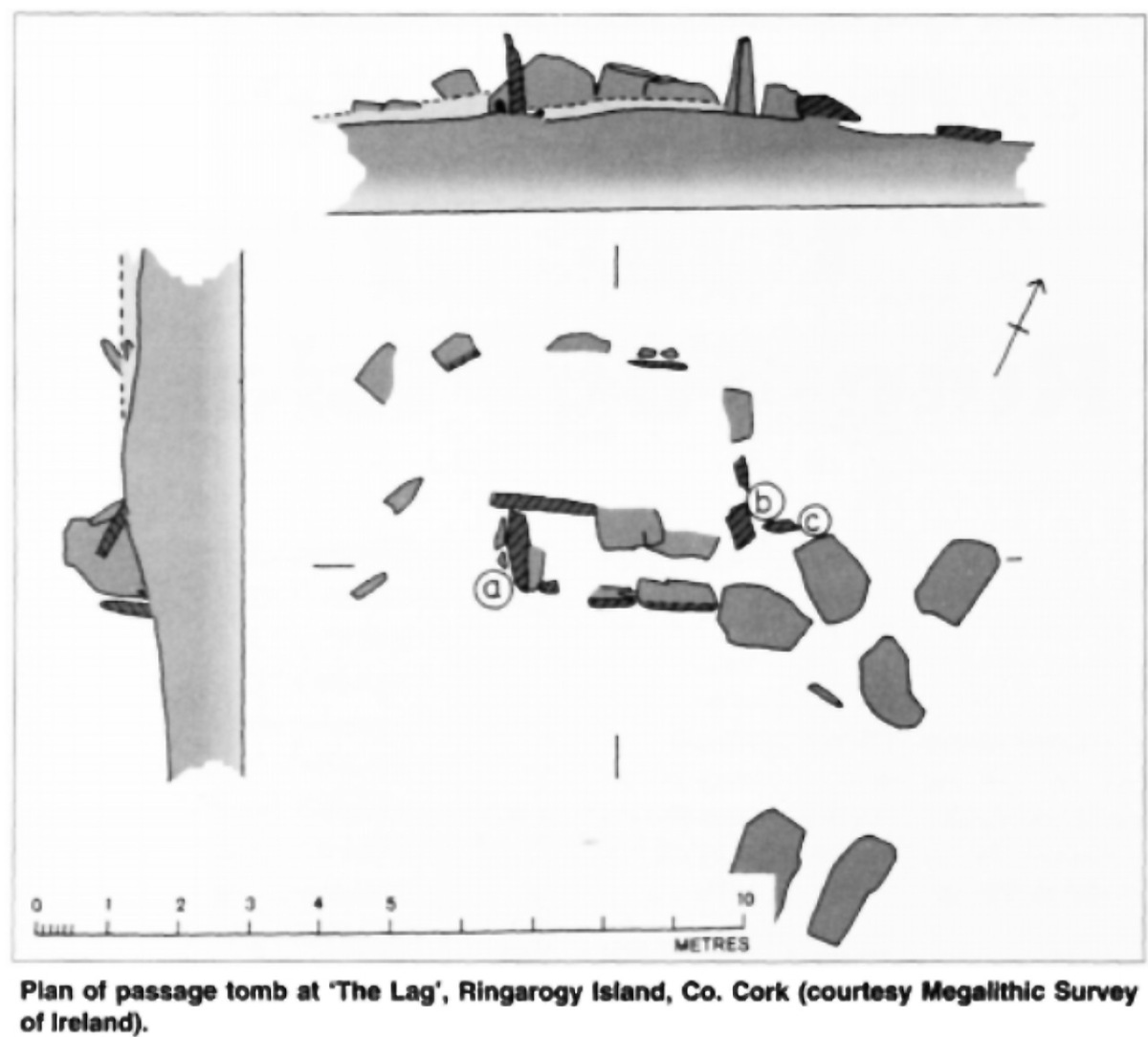

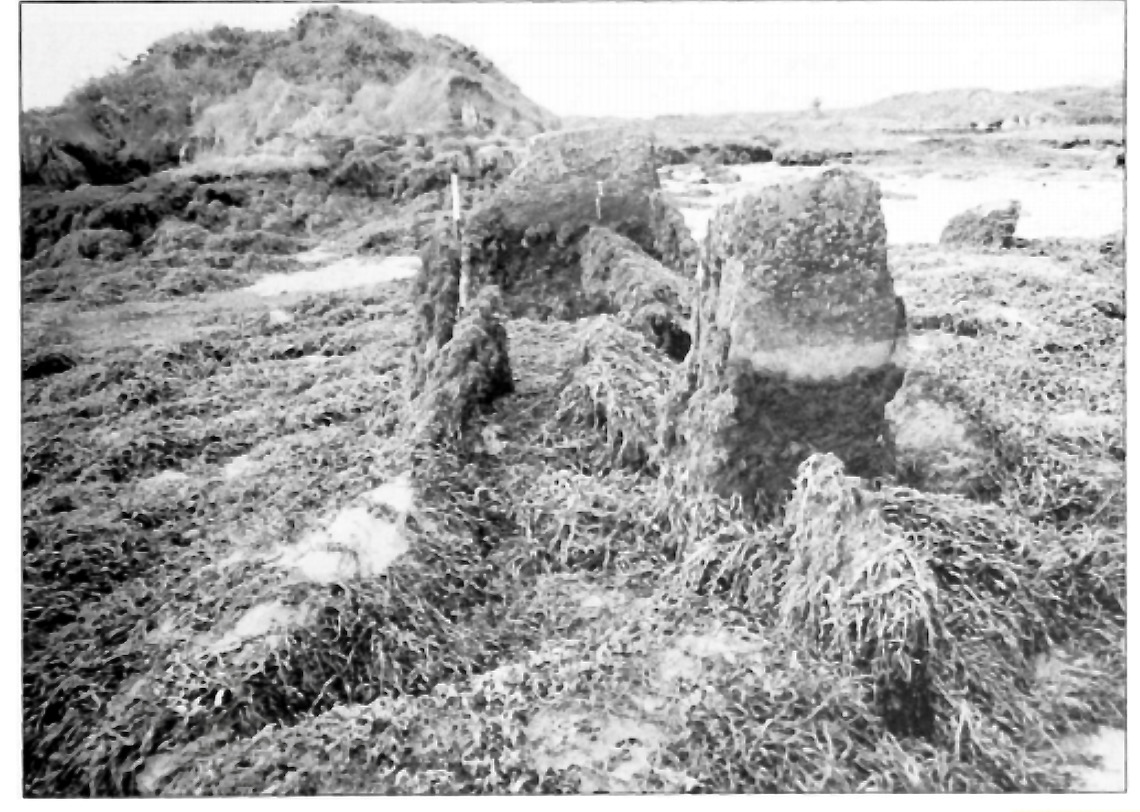

This track leads upwards to an intriguing cairn (another of the anomalous structures that I wrote about last week). There’s a memorial bench to a man who used to come here to commune with nature – and you can see why he would. Last time we were there, the bench needed repair but it’s now perfect again – thank you, anonymous fixer!

There are fabulous vistas from the top – on this occasion it afforded us a magnificent view of the squall that was heading our direction, over Mounts Corrin and Gabriel. It was our cue to dash back down again.