Rock art can be astounding or underwhelming. What makes it one or the other is light.

This is the rock I labelled Derrynablaha 3. My 1973 drawing of it is below. From it, there’s a clear view across to Lough Brin to the east, and all the way down the Kealduff River.

Irish prehistoric rock art likely dates from the Neolithic, about 5,000 years ago. We’ve written extensively about rock art (and indeed about Derrynablaha) – see all our posts on this special menu page. There are significant concentrations in Kerry, including 49 pieces identified so far in the adjoining townlands of Derrynablaha and Derreeny, in the middle of the Iveragh Peninsula. To get there, turn north from the Blackwater Bridge and head for the Ballaghbeama Gap.

If you go on a grey day with no shadows (all too common in our part of the world), or even when the sun is high in the heavens, you might see nothing at all. You might walk right by a piece of rock art without realising it was there. We visited Derrynablaha this week and were very lucky to hit it just right.

By ‘just right’ I mean that we had a sunny day, not a cloud to be seen, and because it’s winter and we got there earlyish in the morning the sun was low in the sky. That kind of low, raking light creates the best possible natural conditions for viewing rock art, as demonstrated in this post – Aoibheann Lambe’s excellent capture shows how to do it. There are other ways to do it, of course – you can use strategically placed coordinated flashes – something Ken Williams is rightly famous for. You can go at night with strong lights, or you can use photogrammetry to produce a 3D image. But for a truly immersive experience, seeing it on a day like we had is an experience that is hard to beat.

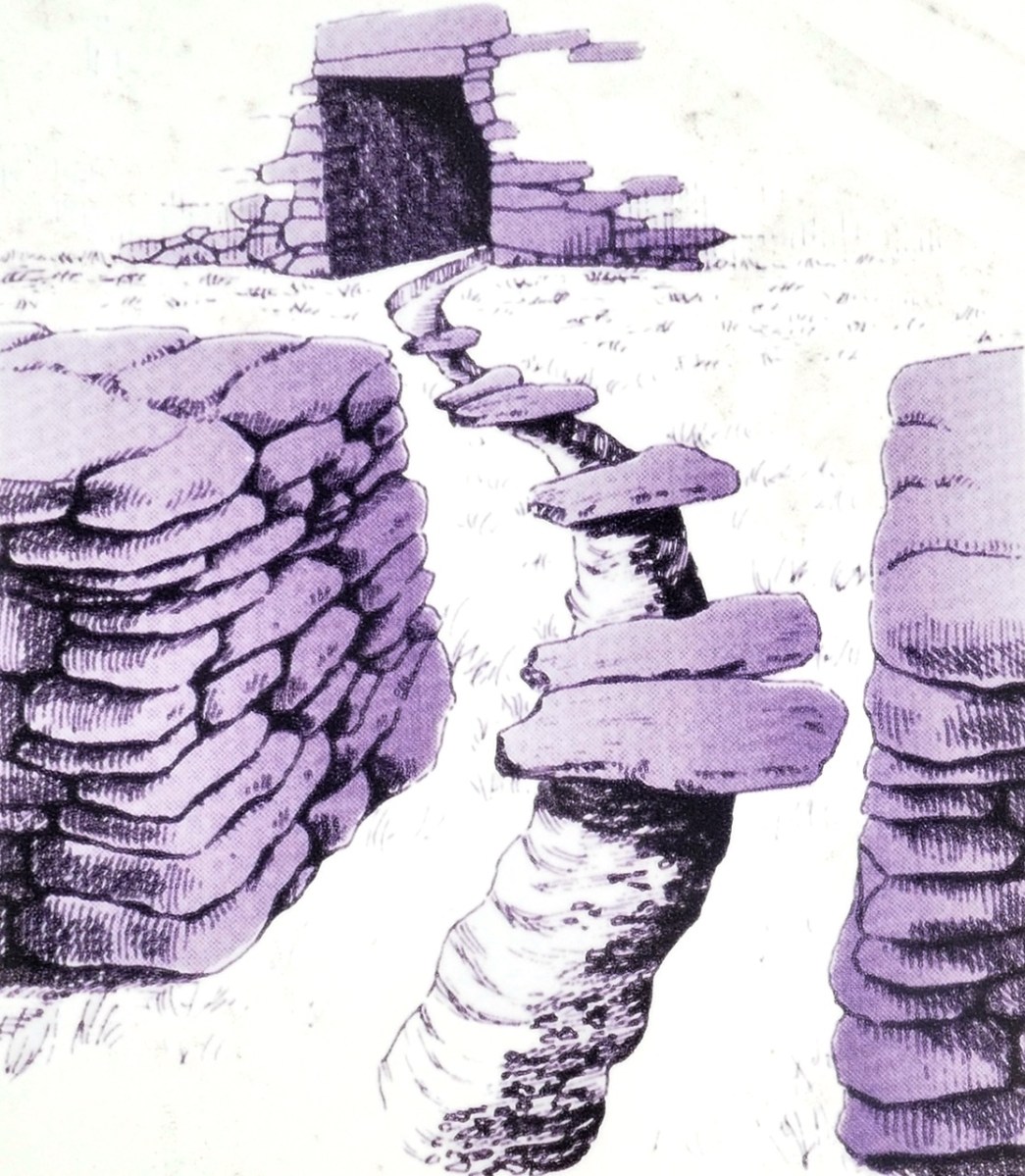

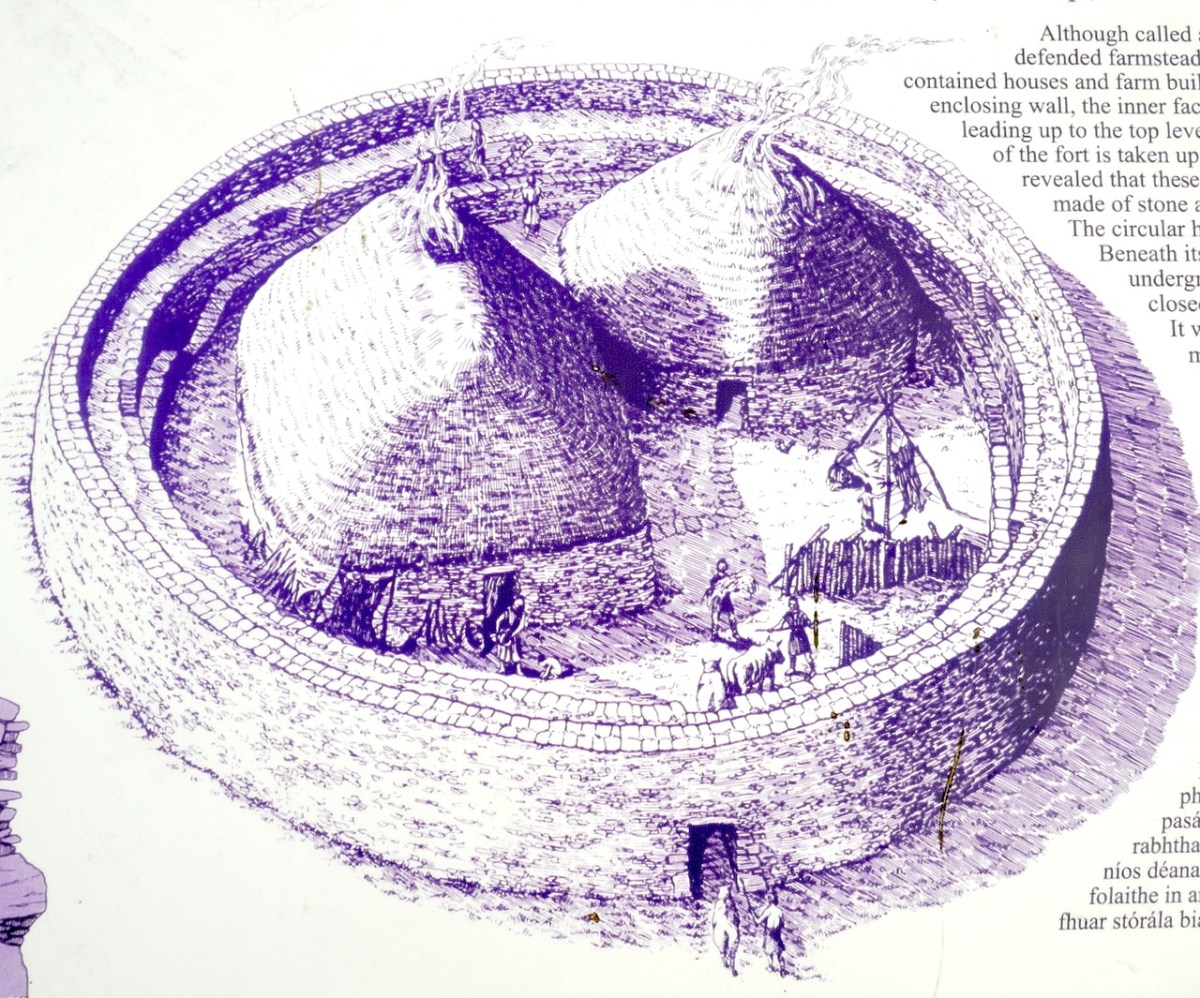

I spent time recording all the known Derrynablaha rock art when I was doing my thesis in archaeology at UCC in 1972. The carvings had been discovered by the landowner, Daniel O’Sullivan, who wrote to the Department of Archaeology in 1962. His brother, John, still lived on the farm when I was doing my fieldwork, in the farmhouse that is now a ruin (above) but which still holds happy memories for me. The remains of a more ancient settlement are also clearly visible (below).

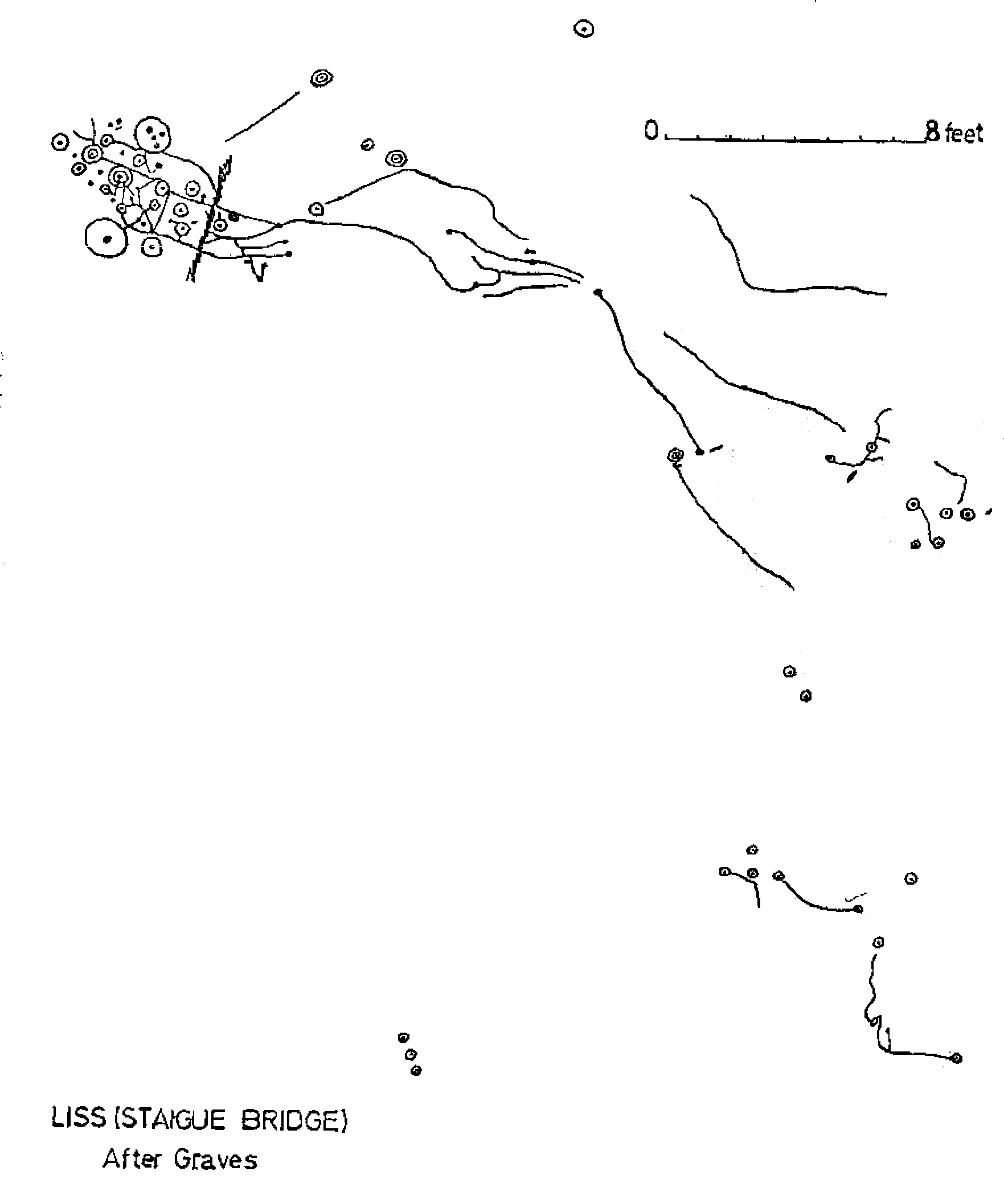

They were visited by the Italian archaeologist Emmanuel Anati the following year, 1963, at Prof O’Kelly’s suggestion and it was Anati who first wrote about this site. Anati, by the way, went on to found a centre for rock art research at Val Camonica in Italy, and as far as I can tell is still alive and active, in his 90s. He recorded 15 panels.

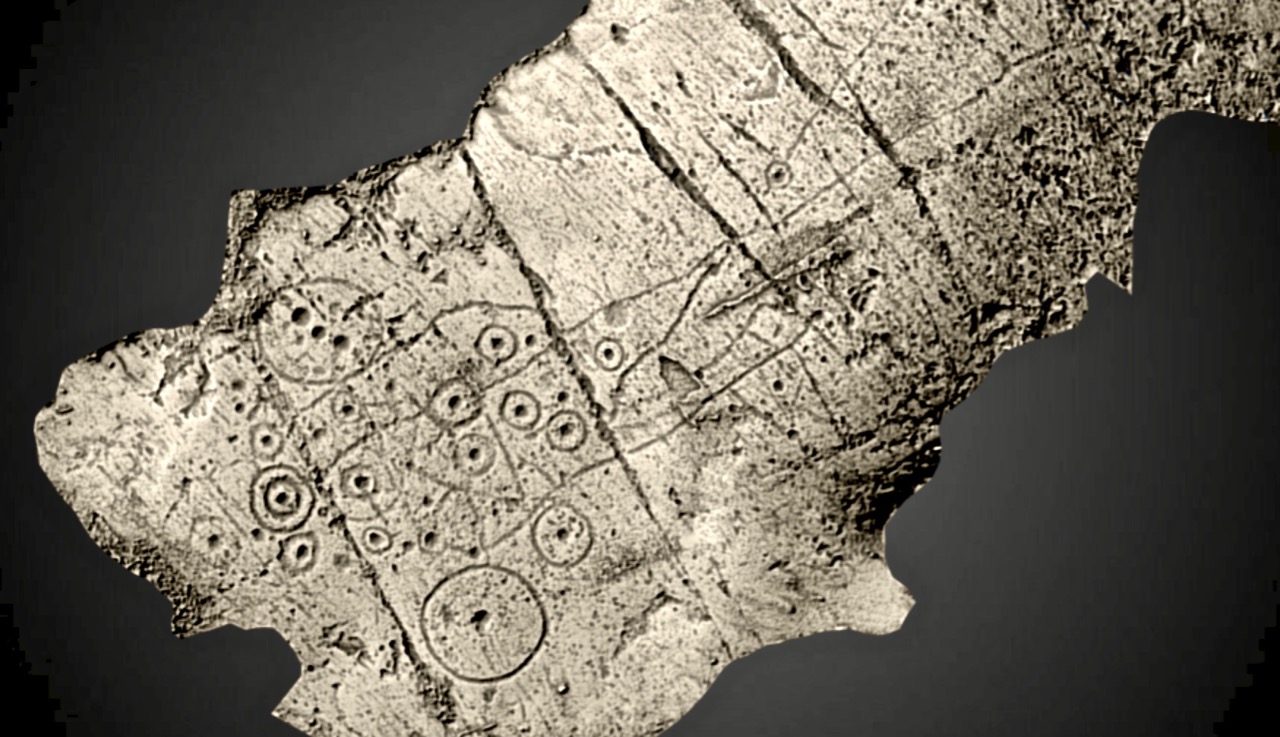

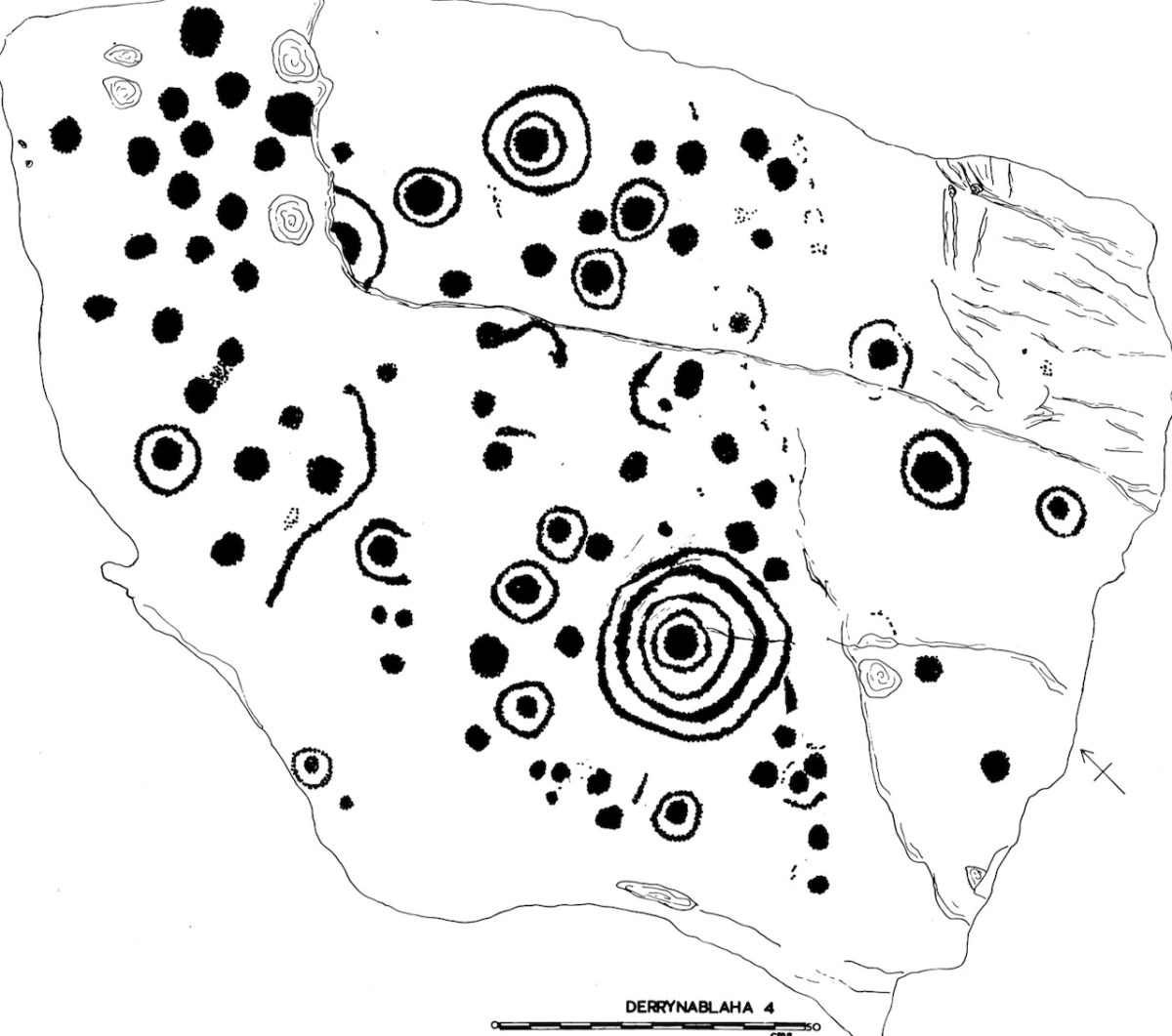

This is my Derrynablaha 4

Subsequent expeditions from UCC, and my own explorations, resulted in a grand total of 23 examples being included in my thesis. By the time of the Kerry Archaeological survey in the 1980s there were 26 pieces identified, and more have been found since then – there are now 29 known panels of rock art in Derrynablaha and a further 20 in Derreeny.

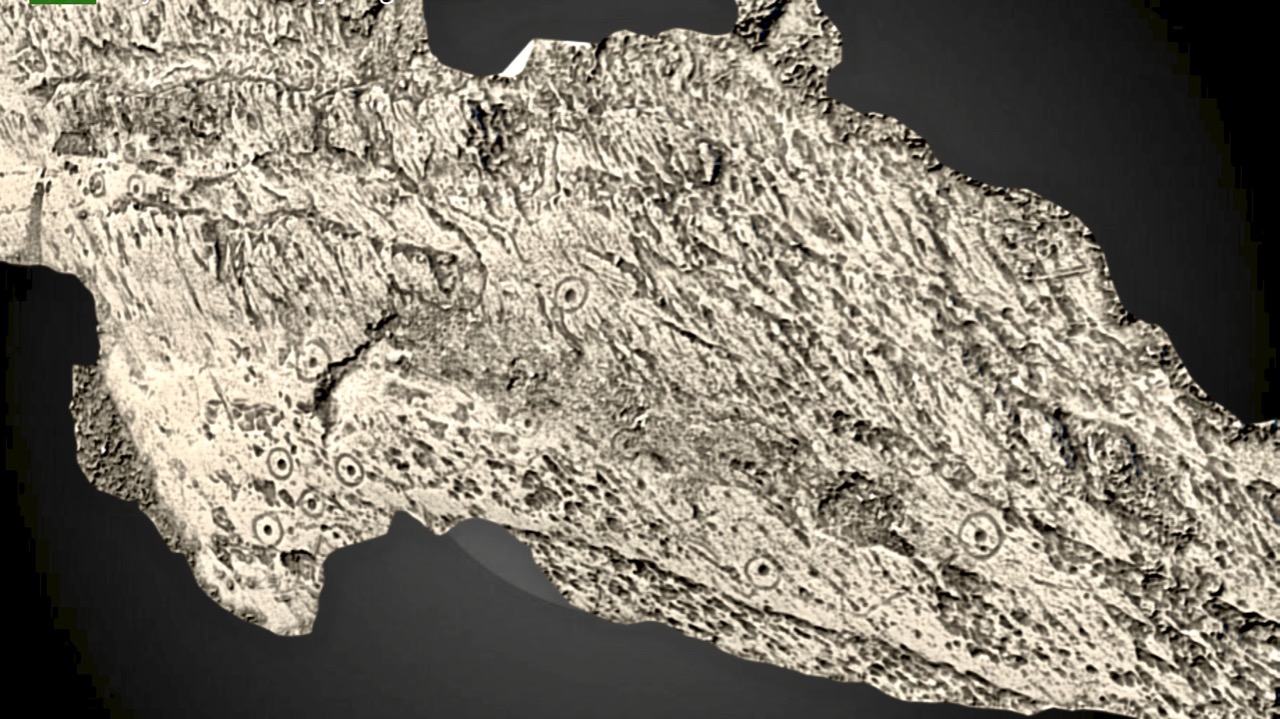

A detail from Derrynablaha 4 clearly showing individual pick marks. The decoration was picked on using stone-on-stone percussion. You can also see how ice can settle on the surface and over time cause cracking damage. My drawing of this stone is below

They are very hard to find unless you know exactly where to go, and I was very lucky indeed to have the expert guidance of Google. Yes – there is a Google Map devoted to Irish rock art! It’s the brainchild of Caimin O’Brien of the National Monuments Service and with it on your phone it’s possible to tramp over the hillsides and locate each piece. We are supremely grateful to Caimin for the work he has done on this, and we only wish all National Monuments could get the same treatment!

Even with this amazing resource, this is not an easy field trip. The ground is steep, rough and wet, and there are barbed wire fences to find a way around. It’s an active sheep pasture, so it’s important to be mindful that you are on private property and be respectful of all farm boundaries.

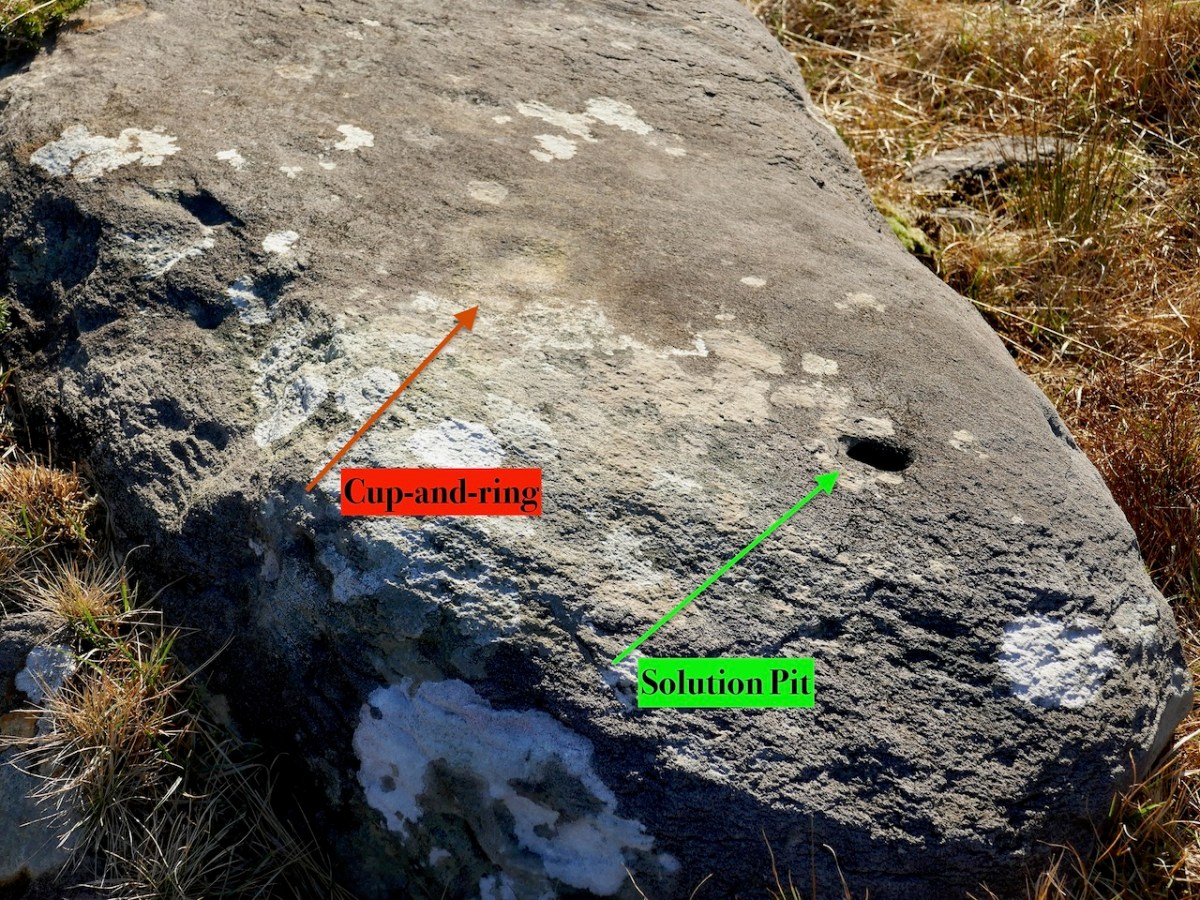

This is a good example of rock art that could be easily overlooked. A very faint cup-and-ring can be seen in good light conditions. The obvious hole, however, is not a cupmark but a naturally occurring solution pit

Because we only had half a day, we confined our walk to the area around the old farmhouse and the hillside to the west of it, and managed to visit 8 panels. Even in the perfect lighting conditions we had, not all are easy to see, as they have been exposed for thousands of years and have worn away. But, for the most part, once we had found the rock, we could see the carvings clearly.

All the panels we viewed had cupmarks and cup-and-ring marks, as well as some pecked lines meandering across the surface. We don’t know what the significance of these motifs are, although theories abound. There are other motifs at Derrynablaha too, all falling within the repertoire of classic rock art.

Our companions on this day, as on so many of our adventures, were Amanda and Peter of Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry. And of course several holy wells were on the agenda too, including this one near Kenmare. Take a look at Amanda’s brief write up on her Facebook page, or keep an eye on her excellent blog for more about our finds on this trip.

We’ve written about Derrynablaha so many times now – why do I know this won’t be the last time?